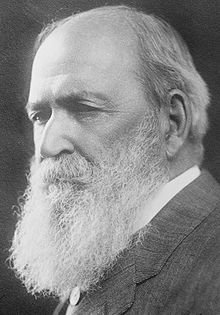

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (October 23, 1831 – January 9, 1924) was an American classical scholar. An author of numerous works, and founding editor of the American Journal of Philology, he has been credited with contributions to the syntax of Greek and Latin, and the history of Greek literature.[1]

Basil L. Gildersleeve | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve October 23, 1831 |

| Died | January 9, 1924 (aged 92) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Classical philology professor |

| Known for | Founder of the American Journal of Philology |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | Princeton University (BA) University of Bonn University of Göttingen (PhD) |

| Academic advisors | Johannes Franz Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl Friedrich Wilhelm Schneidewin |

| Academic work | |

| Institutions | University of Virginia Johns Hopkins University |

| Signature | |

Early life and education

editGildersleeve was born in Charleston, South Carolina, to Emma Louisa Lanneau, daughter of Bazille Lanneau and Hannah Vinyard, and Benjamin Gildersleeve (1791–1875). His father was a Presbyterian evangelist, and editor of the Charleston Christian Observer from 1826 to 1845, of the Richmond, Virginia Watchman and Observer from 1845 to 1856, and of The Central Presbyterian from 1856 to 1860.

His maternal grandfather was Bazile Lanneau (born Basile Lanoue), one of the many French Acadians who were forcibly expelled by the British from present day Nova Scotia during the French and Indian War. His maternal grandmother was Hannah Vinyard.

Gildersleeve graduated from Princeton University in 1849 at the age of eighteen, and went on to study under Johannes Franz in Berlin, under Friedrich Ritschl at Bonn and under Friedrich Wilhelm Schneidewin at Göttingen, where he received his PhD in 1853.

Career

editUpon returning to the United States, he was offered a position as a Classics professor at Princeton University, but he turned it down.[2] From 1856 to 1876, he was professor of Greek at the University of Virginia, holding the chair of Latin also from 1861 to 1866.[3] He married Eliza Fisher Colston on September 18, 1866 in Middlebury, Virginia. After service for the Confederate States Army in the American Civil War, during which Gildersleeve was shot in the leg, he returned to the University of Virginia.[4]

Johns Hopkins University

editTen years later, he accepted an offer from Daniel Coit Gilman to teach at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.[5] When the Johns Hopkins University opened in 1876, Gildersleeve was one of five original full professors and was responsible for setting up a program in the study of Greek and Roman literature, at which he succeeded admirably. He chose junior faculty and graduate students who went on to make a major impact in classical studies, at Johns Hopkins and elsewhere. His hiring also helped to reassure the Baltimore community that the new university was not just a northern institution transplanted south. Johns Hopkins was known to be opposed to slavery, founding president Daniel Coit Gilman was from Connecticut, and most other faculty were from the northern states, which led to suspicion regarding the intent of the new institution.[6]

In 1880, the American Journal of Philology, a quarterly published by the Johns Hopkins University, was established under his editorial charge, and his strong personality was expressed in the department of the Journal headed "Brief Report" or "Lanx Satura," and in the earliest years of its publication every tiny detail was in his hands. His style in it, as elsewhere, is in striking contrast to that of the typical classical scholar, and accords with his conviction that the true aim of scholarship is "that which is." He published a Latin Grammar (1867; revised with the cooperation of Gonzalez B. Lodge, 1895 and 1899; reprinted 1997 with a bibliography of twentieth-century work on the subject)[7] and a Latin Series for use in secondary schools (1875), both marked by lucidity of order and mastery of grammatical theory and methods. His edition of Persius (1875) has been attributed great value.[3]

Gildersleeve's bent was toward Greek more than Latin. His special interest in Christian Greek was partly the cause of his editing the Apologies of Justin Martyr (1877), which claimed to have "used unblushingly as a repository for [his] syntactical formulae." Gildersleeve's studies under Franz had no doubt quickened his interest in Greek syntax, and his logic, untrammeled by previous categories, and his marvelous sympathy with the language were displayed in this most unlikely of places. His Syntax of Classic Greek (Part I, 1900, with CWE Miller) collects these formulae. Gildersleeve edited in 1885 The Olympian and Pythian Odes of Pindar, with what was called "a brilliant and valuable introduction." His views on the function of grammar were summarized in a paper on The Spiritual Rights of Minute Research delivered at Bryn Mawr on June 16, 1895. His collected contributions to literary periodicals appeared in 1890 under the title Essays and Studies Educational and Literary.[3]

The Atlantic Monthly published an article by Gildersleeve titled "The Creed of the Old South" in January 1892, and an essay, "A Southerner in the Peloponnesian War", in September 1897. Johns Hopkins Press later published them in a book in 1915.[8]

He was elected president of the American Philological Association in 1877 and again in 1908 and became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters as well as of various learned societies. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1896 and the American Philosophical Society in 1903.[9][10] He received the honorary degree of LL.D. from William and Mary (1869), Harvard (1896), Yale (1901), Chicago (1901),[11] and Pennsylvania (1911); D.C.L. from the University of the South (1884); L.H.D. from Yale (1891) and Princeton (1899); and Litt.D. from Oxford and Cambridge (1905).

Death and legacy

editGildersleeve retired from teaching in 1915. He died on January 9, 1924, and was buried at the University of Virginia Cemetery in Charlottesville, Virginia. In a memorial published in the American Journal of Philology, Professor C. W. E. Miller paid tribute to Gildersleeve, stating, "Of Greek authors, there were few with whom he did not have more than a bowing acquaintance."[12]

In more recent years, Gildersleeve has received critical attention for his unapologetic defense of slavery, during and after the Civil War. In Soldier and Scholar: Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve and the American Civil War, Ward Briggs published editorials written by Gildersleeve while he served as a staff officer in the Confederate Army and as a professor at the University of Virginia, which feature vitriolic attacks on critics of slavery with parallels drawn to ancient Greek authors and situations. He expressed his contempt for Confederate President Jefferson Davis, whom he considered inept. Jews also came under attack in his writings, including Confederate cabinet officer Judah P. Benjamin, and those accused of miscegenation.[13]

Gildersleeve House, one of the undergraduate dormitories at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and Gildersleeve Portal at Brown Residential College at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia, are both named in his honor. His granddaughter Katherine Lane Weems made the two rhinoceros sculptures at Harvard University.

Fannie Manning Gildersleeve, a black woman born approximately 1869, lists Basil Gildersleeve as her father on her funeral records. Fannie Gildersleeve was married to Charlottesville, Virginia educator Benjamin Tonsler.[14]

The University of Virginia's Classics program offers a distinguished professorship in Gildersleeve's honor. It is currently held by Anthony Corbeill.[15]

References

edit- ^ Gilman, Daniel Coit; Peck, Harry Thurston; Colby, Frank Moore, eds. (1902). "GILDERSLEEVE, BASIL LANNEAU". The New International Encyclopedia. New York: Dodd, Mead. p. 370. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Leitch, Alexander (1978). "Gildersleeve, Basil Lanneau". Princeton University. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gildersleeve, Basil Lanneau". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–13.

- ^ Stimpert, James (September 18, 2000). "Hopkins History: First Greek Prof, Basil Gildersleeve". The Johns Hopkins Gazette. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve; Ward W. Briggs (1998). Soldier and Scholar: Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve and the Civil War. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1743-6.

- ^ John C. French, A History of the University Founded by Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, 1946, pp. 35-36

- ^ Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve; Gonzalez Lodge (1903). Gildersleeve's Latin Grammar. New York, Boston University Publishing Company.

- ^ Gildersleeve, Basil L. (1915). The Creed of the Old South, 1865-1915. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press (Project Gutenberg). Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. 2023-02-09. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ "Past Honorary Degree Recipients". University of Chicago. Retrieved 30 September 2020./

- ^ CWE Miller, "Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve," American Journal of Philology, Vol. 45, p 99

- ^ Ward Briggs, Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve and the Civil War, Charlottesville, VA, 1998

- ^ "J.F. Bell Funeral Home Records Search Results". The Virginia Center for Digital History (VCDH). Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Anthony Corbeill". University of Virginia. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

External links

edit- Basil L. Gildersleeve at the Database of Classical Scholars

- Works by Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Basil L. Gildersleeve at the Internet Archive

- Works by Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, at Hathi Trust

- Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1900), Syntax of Classical Greek Archived 2015-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Gildersleeve, Basil Lanneau". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Gikandi, Simon: "Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve"