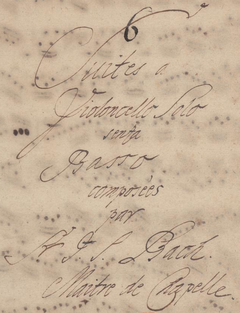

The six Cello Suites, BWV 1007–1012, are suites for unaccompanied cello by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750). They are some of the most frequently performed solo compositions ever written for cello. Bach most likely composed them during the period 1717–1723, when he served as Kapellmeister in Köthen. The title given on the cover of the Anna Magdalena Bach manuscript was Suites à Violoncello Solo senza Basso (Suites for cello solo without bass).

| Cello Suites | |

|---|---|

BWV 1007 to 1012 | |

| by J. S. Bach | |

Title page of Anna Magdalena Bach's manuscript: Suites á Violoncello Solo senza Basso | |

| Composed | between 1717 and 1723 |

| Instrumental | Cello solo |

As usual in a Baroque musical suite, after the prelude which begins each suite, all the other movements are based around baroque dance types.[1] The cello suites are structured in six movements each: prelude, allemande, courante, sarabande, two minuets or two bourrées or two gavottes, and a final gigue.[2] Gary S. Dalkin of MusicWeb International called Bach's cello suites "among the most profound of all classical music works"[3] and Wilfrid Mellers described them in 1980 as "Monophonic music wherein a man has created a dance of God".[1][4]

Due to the works' technical demands, étude-like nature, and difficulty in interpretation because of the non-annotated nature of the surviving copies and the many discrepancies between them, the cello suites were little known and rarely publicly performed in the modern era until they were recorded by Pablo Casals (1876–1973) in the early 20th century. They have since been performed and recorded by many renowned cellists and have been transcribed for numerous other instruments; they are considered some of Bach's greatest musical achievements.[5]

History

editAn exact chronology of the suites (regarding both the order in which the suites were composed and whether they were composed before or after the solo violin sonatas) cannot be completely established. Scholars generally believe that—based on a comparative analysis of the styles of the sets of works—the cello suites arose first, effectively dating the suites earlier than 1720, the year on the title page of Bach's autograph of the violin sonatas.[6]

The suites were not widely known before the early 20th century.[7] It was Pablo Casals who first began to popularize the suites, after discovering an edition by Friedrich Grützmacher (who was the first cellist to perform an entire Bach suite) in a thrift shop in Barcelona in 1889 when he was 13. Although Casals performed the suites publicly, it was not until 1936, when he was 60 years old, that he agreed to record them, beginning with Suites Nos. 2 and 3, at Abbey Road Studios in London. The other four were recorded in Paris: 1 and 6 in June 1938, and 4 and 5 in June 1939. Casals became the first to record all six suites; his recordings are still available and respected today.[8] In 2019, the Casals recording was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[9]

The suites have since been performed and recorded by many cellists. Yo-Yo Ma won the 1985 Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance for his album Six Unaccompanied Cello Suites. János Starker won the 1998 Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance for his fifth recording of Six Unaccompanied Cello Suites.

Manuscript

editUnlike with Bach's solo violin sonatas, no autograph manuscript of the Cello Suites survives, making it impossible to produce modern urtext performing editions. Analysis of secondary sources, including a hand-written copy by Bach's second wife, Anna Magdalena, has produced presumably authentic editions, although critically deficient in the placement of slurs and other articulations, devoid of basic performance markings such as bowings and dynamics, and with spurious notes and rhythms. As a result, the texts present performers with numerous problems of interpretation.[10]

German cellist Michael Bach has stated that he believes the manuscripts of the suites by Anna Magdalena Bach are accurate. According to his analysis, the unexpected positioning of the slurs corresponds closely to the harmonic development, which he suggests supports his theory.[11] His position is not universally accepted. The most recent studies[which?] into the relationships among the four manuscripts show that Anna Magdalena Bach's manuscript may not have been copied directly from her husband's holograph but from a lost intervening source. Thus, the slurs in the Magdalena manuscript may not come from Bach himself and would not be clues to their interpretation.[citation needed]

Recent research has suggested that the suites were not necessarily written for the familiar cello played between the legs (da gamba), but an instrument played rather like a violin, on the shoulder (da spalla). Variations in the terminology used to refer to musical instruments during this period have led to modern confusion, and the discussion continues about what instrument "Bach intended", and even whether he intended any instrument in particular. Sigiswald Kuijken and Ryo Terakado have both recorded the complete suites on this "new" instrument, known today as a violoncello (or viola) da spalla;[12] reproductions of the instrument have been made by luthier Dmitry Badiarov.[13]

Editions

editThe cellist Edmund Kurtz published an edition in 1983, which he based on facsimiles of the manuscript by Anna Magdalena Bach, placing them opposite each printed page. It was described as "the most important edition of the greatest music ever written for the instrument".[14] However, Kurtz chooses to follow the Magdalena text exactly, leading to differences between his and other editions, which correct what are generally considered to be textual errors in the source.[15]

Arrangements

editBach transcribed at least one of the suites, Suite No. 5 in C minor, for lute. An autograph manuscript of this version exists as BWV 995.[16]

Using the Bach edition prepared by cellist Johann Friedrich Dotzauer and published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1826, Robert Schumann wrote arrangements with piano accompaniment for all six Bach cello suites.[17] Schumann's publisher accepted his arrangements of the Bach violin sonatas in 1854, but rejected his Bach cello-suite arrangements.[18] His only cello-suite arrangement surviving is the one for Suite No. 3, discovered in 1981 by musicologist Joachim Draheim in an 1863 transcription by cellist Julius Goltermann.[17][18] It is believed that Schumann's widow Clara Schumann, along with violinist Joseph Joachim, destroyed his Bach cello-arrangement manuscripts sometime after 1860, when Joachim declared them substandard.[17][18] Writing in 2011, Fanfare reviewer James A. Altena agreed with that critique, calling the surviving Bach-Schumann cello/piano arrangement "a musical duckbilled platypus, an extreme oddity of sustained interest only to 19th-century musicologists".[17]

Joachim Raff, in 1868 while working on his own suites for solo piano and for other ensembles, made arrangements of the suites for piano solo, published from 1869 to 1871 by Rieter-Biedermann.[19]

In 1923, Leopold Godowsky composed piano transcriptions of Suites Nos. 2, 3, and 5, in full counterpoint for solo piano, subtitling them "very freely transcribed and adapted for piano".[20]

The cello suites have been transcribed for numerous solo instruments, including the violin, viola, double bass, viola da gamba, mandolin, piano, marimba, classical guitar, recorder, flute, electric bass, horn, saxophone, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, trombone, euphonium, tuba, ukulele, and charango. They have been transcribed and arranged for orchestra as well.

Structure

editThe suites are in six movements each, and have the following structure and order of movements.

- Prelude

- Allemande

- Courante

- Sarabande

- Galanteries: two minuets in each of Suite Nos. 1 and 2; two bourrées in each of Suite Nos. 3 and 4; two gavottes in each of Suite Nos. 5 and 6

- Gigue

Scholars believe that Bach intended the works to be considered as a systematically conceived cycle, rather than an arbitrary series of pieces. Compared to Bach's other suite collections, the cello suites are the most consistent in order of their movements. In addition, to achieve a symmetrical design and go beyond the traditional layout, Bach inserted intermezzo or galanterie movements in the form of pairs between the sarabande and the gigue.

Only five movements in the entire set of suites are completely non-chordal, meaning that they consist only of a single melodic line. These are the second minuet of Suite No. 1, the second minuet of Suite No. 2, the second bourrée of Suite No. 3, the gigue of Suite No. 4, and the sarabande of Suite No. 5. The second gavotte of Suite No. 5 has but one unison chord (the same note played on two strings at the same time), but only in the original scordatura version of the suite; in the standard tuning version it is completely free of chords.

Suite No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007

editThe prelude, mainly consisting of arpeggiated chords, is the best known movement from the entire set of suites and is regularly heard on television and in films.[21]

Suite No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008

editThe Prelude consists of two parts, the first of which has a strong recurring theme that is immediately introduced in the beginning. The second part is a scale-based cadenza movement that leads to the final, powerful chords. The subsequent allemande contains short cadenzas that stray away from this otherwise very strict dance form. The first minuet contains demanding chord shiftings and string crossings.

Suite No. 3 in C major, BWV 1009

editThe Prelude of this suite consists of an A–B–A–C form, with A being a scale-based movement that eventually dissolves into an energetic arpeggio part; and B, a section of demanding chords. It then returns to the scale theme, and ends with a powerful and surprising chord movement.

The allemande is the only movement in the suites that has an up-beat consisting of three semiquavers instead of just one, which is the standard form.

The second bourrée, though in C minor, has a two-flat (or G minor) key signature. This notation, common in pre-Classical music, is sometimes known as a partial key signature. The first and second bourrée of the 3rd Suite are sometimes used as solo material for other bass instruments such as the tuba, euphonium, trombone and bassoon.

Suite No. 4 in E♭ major, BWV 1010

editSuite No. 4 is one of the most technically demanding of the suites, as E♭ is an uncomfortable key on the cello and requires many extended left hand positions. The key is also difficult on cello due to the lack of resonant open strings.[22] The prelude primarily consists of a difficult flowing quaver movement that leaves room for a cadenza before returning to its original theme.

The very peaceful sarabande is quite obscure about the stressed second beat, which is the basic characteristic of the 3

4 dance, since, in this particular sarabande, almost every first beat contains a chord, whereas the second beat most often does not.

Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011

editSuite No. 5 was originally written in scordatura with the A-string tuned down to G, but nowadays a version for standard tuning is included in almost every printed edition of the suites along with the original version. Some chords must be simplified when playing with standard tuning, but some melodic lines become easier as well.

The Prelude is written in an A–B form, and is a French overture. It begins with a slow, emotional movement that explores the deep range of the cello. After that comes a fast and very demanding single-line fugue that leads to the powerful end.

This suite is most famous for its intimate sarabande, which is one of the few movements in the six suites that does not contain any double stops (chords). Mstislav Rostropovich described it as the essence of Bach's genius. Paul Tortelier viewed it as an extension of silence. Rostropovich, extending Tortelier's "silence" to an extreme, would sometimes play the Sarabande as a recital encore at a metronome marking of 32 or slower, one note per beat, with no vibrato and no slurs, each note standing alone in a "well of silence". Yo-Yo Ma played this movement on September 11, 2002 at the site of the World Trade Center, while the names of the dead were read on the first anniversary of remembrance of those lost in the September 11 attacks.

The 5th Suite is also exceptional as its courante and gigue are in the French style, rather than in the Italian form of the other five suites.

An autograph manuscript of Bach's lute version of this suite exists as BWV 995.[16]

Suite No. 6 in D major, BWV 1012

editIt is widely believed that Suite No. 6 was composed specifically for a five-stringed violoncello piccolo, a smaller cello, roughly 7⁄8 normal cello size with a fifth upper string tuned to E, a perfect fifth above the otherwise top string. However, some say there is no substantial evidence to support this claim: whilst three of the sources inform the player that it is written for an instrument à cinq cordes, only Anna Magdalena Bach's manuscript indicates the tunings of the strings, and the other sources do not mention any intended instrument at all.

Other possible instruments for the suite include a cello da spalla, a version of the violoncello piccolo played on the shoulder like a viola, as well as a viola with a fifth string tuned to E, called a viola pomposa. As the range required in this piece is very large, the suite was probably intended for a larger instrument, although it is conceivable that Bach—who was fond of the viola—may have performed the work himself on an arm-held violoncello piccolo. However, it is equally likely that beyond hinting the number of strings, Bach did not intend any specific instrument at all as the construction of instruments in the early 18th century was highly variable.

Cellists playing this suite on a modern four-string cello encounter difficulties as they are forced to use very high positions to reach many of the notes. Performers specialising in early music and using authentic instruments generally use the five-string cello for this suite. The approach of Watson Forbes, in his transcription of this suite for viola, was to transpose the entire suite to G major, avoiding "a tone colour which is not very suitable for this type of music" and making most of the original chords playable on a four-stringed instrument.[23]

This suite is written in much more free form than the others, containing more cadenza-like movements and virtuosic passages. It is also the only one of the suites that is partly notated in the alto and soprano clefs (modern editions use tenor and treble clefs), which are not needed for the others since they never go above the note G4 (G above middle C).

Mstislav Rostropovich called Suite No. 6 "a symphony for solo cello" and characterised its D major tonality as evoking joy and triumph.

Speculations about Anna Magdalena Bach

editProfessor Martin Jarvis of Charles Darwin University School of Music, in Darwin, Australia, speculated in 2006 that Anna Magdalena may have been the composer of several musical pieces attributed to her husband.[24] Jarvis proposes that Anna Magdalena wrote the six Cello Suites and was involved in composing the aria from the Goldberg Variations (BWV 988). Musicologists, critics, and performers, however, pointing to the thinness of evidence of this proposition, and the extant evidence that supports Johann Sebastian Bach's authorship, remain skeptical of the claim.[24][25]

References

edit- ^ a b Wittstruck, Anna. "Dancing with J.S. Bach and a Cello – Introduction" Archived 2013-03-25 at the Wayback Machine. Stanford University. Stanford.edu. 2012.

- ^ de Acha, Rafael. "Review: Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750): Six suites for unaccompanied cello, Carmine Miranda (cello), CENTAUR CRC3263/4". MusicWeb International. 2012.

- ^ Dalkin, Gary S. "J.S. Bach: Cello Suites. Heinrich Schiff. EMI Double Fforte CZS 5741792". MusicWeb International. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- ^ Mellers, Wilfrid. Bach and the Dance of God. Faber and Faber, 1980. p. 15.

- ^ Proms 2015. Prom 68: Bach – Six Cello Suites. BBC. 5 September 2015.

- ^ Sevier, Zay David (1981). "Bach's Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas: The First Century and a Half, Part 1". Bach. 12 (2): 11–19. ISSN 0005-3600. JSTOR 41640128.

- ^ Rutherford, David. "The Story Behind the Bach Cello Suites, And Why We Still Love Them Today". Colorado Public Radio. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- ^ Sanderson, Blair. "J.S. Bach: Six Suites for Solo Cello – Pablo Casals". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

... Casals still seems to be the standard against which other performances are measured, and these recordings are indispensable to any serious collector.

- ^ Andrews, Travis M. (March 20, 2019). "Jay-Z, a speech by Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and 'Schoolhouse Rock!' among recordings deemed classics by Library of Congress". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ Bromberger, Eric. Program Notes: The University of Chicago Presents | Performance Hall | Logan Center. October 15, 2013, 7:30 PM. Jean-Guihen Queyras, cello Archived November 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. October 2013. p. 2.

- ^ Finckh, Eckhard. "Kritischer Blick auf Cello-Suiten" (in German). Nürtinger Zeitung. 8 May 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ Kuijken, Sigiswald. "Sigiswald Kuijken over de 'violoncello da spalla'" Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch). PreludeKlassiekeMuziek.nl. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Badiarov, Dmitry. "J.S. Bach – Violoncello da Spalla Suites". The Violin Blog of Dmitry Badiarov – violin-maker. 29 August 2010.

- ^ Campbell, Margaret (2004-08-23). "Edmund Kurtz". The Independent. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ^ Szabó, Zoltán. 2016. Problematic sources, problematic transmission: An outline of the edition history of the solo cello suites. PhD dissertation, The University of Sidney.

- ^ a b BWV995 Archived 2009-09-04 at the Wayback Machine at JSBach.org. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Altena, James A. Review of 'Schumann: Chamber Music Vol 2 - Cello And Piano / Ensemble Villa Musica' Archived 2020-10-26 at the Wayback Machine. Fanfare. 2011. Reprinted at ArkivMusic.

- ^ "Raff Work Catalog: Arrangements of Works by Others". Archived from the original on 2020-09-19. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- ^ Siblin, Eric. The Cello Suites: J. S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque Masterpiece. Grove/Atlantic, 2011. p. 215.

- ^ Winold, Allen (2007). Bach Cello Suites Analyses & Explorations Volume I: Text. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780253218858.

- ^ Timmons, Lena (2012). "Using the Organ to Teach the Fourth Suite Prelude for Violoncello Solo by J.S. Bach" (PDF). libres.uncg.edu. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Bach, J.S. (composer) and Watson Forbes (transcriber and editor). Six Suites for Viola (Originally for Cello). J. & W. Chester Ltd., 1951. Preface.

- ^ a b Dutter, Barbie and Roya Nikkhah. "Bach works were written by his second wife, claims academic". The Telegraph. 23 April 2006.

- ^ Ross, Alex. "The Search for Mrs. Bach". The New Yorker. October 31, 2010.

External links

edit- Anna Magdalena's manuscript

- Manuscript Sources

- Cello Suites: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Johann Sebastian Bach at Grove Music Online

- The Cello Suites of Bach: History – Analysis – Detailed Interpretation – Program Notes – Audio – Video – Comprehensive analysis and notes on interpretation by cellist Georg Mertens

- Audio, commentary, analysis, and history from Stanford University

- History, Baroque Cello, Editions, Recordings, Interpretation jsbachcellosuites.com

- Cello Suite No. 1, Cello Suite No. 2, Cello Suite No. 3, Cello Suite No. 4, Cello Suite No. 5 and Cello Suite No. 6: performances by the Netherlands Bach Society (video and background information)

- MIDI Sequences

- Musical scores and MIDI files at the Mutopia Project