Bagaceratops (meaning "small-horned face") is a genus of small protoceratopsid dinosaurs that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous, around 72 to 71 million years ago. Bagaceratops remains have been reported from the Barun Goyot Formation and Bayan Mandahu Formation. One specimen may argue the possible presence of Bagaceratops in the Djadochta Formation.

| Bagaceratops Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

~ | |

|---|---|

| |

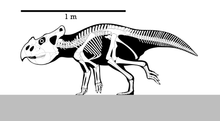

| Skeletal reconstruction (including elements previously described as Magnirostris) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ceratopsia |

| Clade: | †Coronosauria |

| Family: | †Protoceratopsidae |

| Genus: | †Bagaceratops Maryanska & Osmolska, 1975 |

| Type species | |

| †Bagaceratops rozhdestvenskyi Maryanska & Osmolska, 1975

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Bagaceratops was among the smallest ceratopsians, growing up to 1–1.5 m (3.3–4.9 ft) in length, with a weight about 22.7–45 kg (50–99 lb). Although emerging late in the reign of the dinosaurs, Bagaceratops had a fairly primitive anatomy—when compared to the much derived ceratopsids—and kept the small body size that characterized early ceratopsians. Unlike its close relative, Protoceratops, Bagaceratops lacked premaxillary teeth (cylindrical, blunt teeth near the tip of the upper jaw).

History of discovery

editDuring the large field work of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions in the 1970s, abundant protoceratopsid specimens were discovered on eroded surfaces of the Hermiin Tsav locality of the Barun Goyot Formation, Gobi Desert. This newly collected and rich fossil material is stored in the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences (Poland). In 1975, two of the expedition's leading scientists, namely Polish paleontologists Teresa Maryańska and Halszka Osmólska, published a large monograph dedicated to describe this material where they named the new genus and type species of protoceratopsid Bagaceratops rozhdestvenskyi. The selected holotype is ZPAL MgD-I/126, which consists of a relatively medium-sized skull, and a vast majority of the specimens collected by the expeditions were assigned to Bagaceratops, including juvenile and sub-adult skulls. The generic name, Bagaceratops, means "small-horned face" and is derived from the Mongolian baga = meaning small; and Greek ceratops = meaning horn face. The specific name, B. rozhdestvenskyi, is named in honor of the Russian paleontologist Anatoly Konstantinovich Rozhdestvensky for his notorious work on dinosaurs.[1]

Additional specimens

editIn 1993, the Japan-Mongolia Joint Paleontological Expedition collected an articulated and nearly complete Bagaceratops skeleton (MPC-D 100/535) from the Barun Goyot Formation at the Hermiin Tsav locality.[2] In 2010 and 2011 this specimen was examined to analyze several borings (tunnel-like holes) left by invertebrae scavengers on joint areas.[3][4] As of 2019, MPC-D 100/535 remains largely undescribed.[5] In 2019 a partial skeleton (specimen KID 196) of Bagaceratops was described by Bitnara Kim and colleagues, who noted no significant differences between the skeleton of Protoceratops and the former, with the exception of the anatomy of the skull and the shape and location of the clavicles. This specimen was discovered in 2007 also from the Hermiin Tsav locality of the Barun Goyot Formation, and includes a partially preserved skull with partial skeleton of an adult individual.[5]

In 2020, Czepiński described new specimens of Bagaceratops and Protoceratops from the Udyn Sayr and Zamyn Khond localities, respectively, of the Djadochta Formation, and evaluated the implications of these specimens for correlation of fossil sites of the latter formation. He considered one of these specimens in particular, MPC-D 100/551B, as a potential evidence of an anagenetic transition from Protoceratops andrewsi to Bagaceratops rozhdestvenskyi.[6]

Synonyms

editJuvenile remains, at first tentatively named Protoceratops kozlowskii,[1] and then renamed Breviceratops kozlowskii by Kurzanov in 1990,[7] were considered to be juvenile Bagaceratops. Paul Sereno in 2000 explained this by extrapolating that the juvenile Breviceratops would grow into a mature Bagaceratops.[8]

In 2003 Russian paleontologist Vladimir R. Alifanov named the new taxa Lamaceratops tereschenkoi and Platyceratops tatarinovi from the Barun Goyot Formation. Material assigned by Alifanov corresponds to the holotype of Lamaceratops (PIN 4487/26; a partial small-sized skull), recovered from the Khulsan locality, and the holotype of Platyceratops (PIN 3142/4; an almost complete medium-sized skull), found in the red beds of the Hermiin Tsav locality. He also coined the family Bagaceratopidae in order to contain these new taxa and Bagaceratops.[9] Also during 2003, You Hailu and Dong Zhiming described and named the new genus and species of protoceratopsid Magnirostris dodsoni from red beds at the Bayan Mandahu locality of the Bayan Mandahu Formation, Inner Mongolia (China). The holotype of Magnirostris, IVPP V12513, represents a nearly complete skull lacking the frill region of a large individual and was collected during expeditions led by the Sino-Canadian Dinosaur Project.[10] In 2006 Mackoviky regarded all of these ceratopsians as junior synonyms of Bagaceratops based on the reasoning that all exhibit anatomical traits already seen on other specimens of this protoceratopsid, and some of them are likely products of preservation.[11]

In 2008 Alifanov described and named another ceratopsian taxon from the Barun Goyot Formation, Gobiceratops minitus. Its holotype (PIN 3142/299) is represented by a very small and juvenile skull that was collected from the Hermiin Tsav locality near the end of the 1970s by the Joint Soviet–Mongolian Paleontological Expedition. Though Alifanov used this skull to erect the new Gobiceratops, it had already been displayed for several years at the Moscow Paleontological Museum under the name Bagaceratops rozhdestvenskyi.[12]

A comprehensive study on the intraspecific variation in morphology of B. rozhdestvenskyi was conducted by Polish paleontologist Łukasz Czepiński in 2019, where he concluded that the previously named Gobiceratops minutus, Lamaceratops tereschenkoi, Platyceratops tatarinovi and Magnirostris dodsoni represent additional specimens and growth stages of B. rozhdestvenskyi and therefore, junior synonyms. Czepiński reexamined many of the specimens originally described by Maryańska and Osmólska, as well as the respective holotypes of these taxa, providing evidence that all traits used to separate them are, in fact, indistinguishably present on Bagaceratops and they fall within the large intraspecific variation of this taxon. He also considered Breviceratops to be a distinct and separate genus of protoceratopsid, from both Bagaceratops and Protoceratops, as it features a combination of basal (primitive) and derived (advanced) traits.[13]

Description

editBagaceratops was a small-sized protoceratopsid, reaching adult dimensions of about 1–1.5 m (3.3–4.9 ft) in length[14][5] and 22.7–45 kg (50–99 lb) in body mass based on Maginostris.[15] It had a smaller frill, about ten grinding teeth per jaw, and more triangular skull than its close relative, Protoceratops. Although both Bagaceratops and Protoceratops were very similar (mostly in the postcranial skeleton), the former had a much derived (advanced) skull morphology. Bagaceratops lacked primitive premaxillary teeth, had paired (fused) nasal bones, and an oval-shaped fenestra (hole) was developed in the maxilla—otherwise known as accessory antorbital fenestra.[1][13]

Classification

editBagaceratops belonged to Ceratopsia, a group of herbivorous dinosaurs with parrot-like beaks which thrived in North America and Asia during the Cretaceous Period, which ended roughly 66 million years ago.

In 2019 Czepiński analyzed a vast majority of referred specimens to the ceratopsians Bagaceratops and Breviceratops, and concluded that most were in fact specimens of the former. Although the genera Gobiceratops, Lamaceratops, Magnirostris, and Platyceratops, were long considered valid and distinct taxa, and sometimes placed within Protoceratopsidae, Czepiński found the diagnostic features used to distinguish these taxa to be largely present in Bagaceratops and thus becoming synonyms of this genus. Under this reasoning, Protoceratopsidae consists of Bagaceratops, Breviceratops, and Protoceratops. Based on cranial characters such as presence or absence of premaxillary teeth and an antorbital fenestra, P. andrewsi is the basal-most protoceratopsid and Bagaceratops the derived-most one. Below are the proposed phylogenetic relationships within Protoceratopsidae by Czepiński:[13]

Paleoenvironment

editBarun Goyot Formation

editThe Barun Goyot Formation, based on sediments, is regarded as Late Cretaceous in age (Middle-Upper Campanian) and has virtually yielded the bulk of material for which Bagaceratops is known.[16][13] This formation is mostly characterized by series of red beds, mostly light-coloured sands (yellowish, grey-brown, and rarely reddish) that are locally cemented. Sandy claystones (often red-coloured), siltstones, conglomerates, and large-scale trough cross-stratification in sands are also common across the unit. In addition, structureless, medium-grained, fine-grained and very fine-grained sandstones predominate in sediments of the Barun Goyot Formation. The sediments of this formation were deposited in alluvial plain (flat land consisting of sediments deposited by highland rivers), lacustrine, and aeolian paleoenvironments, under relatively arid to semiarid climates.[17][18][16]

Bagaceratops is the most common taxon across the Barun Goyot Formation,[1][13] which was also home to many other vertebrates, including the ankylosaurids Saichania, Tarchia and Zaraapelta;[19][20] alvarezsaurids Khulsanurus and Parvicursor;[21] birds Gobipipus, Gobipteryx and Hollanda;[22] fellow protoceratopsid Breviceratops;[13] dromaeosaurids Kuru and Shri;[23][24] halszkaraptorine Hulsanpes;[25] pachycephalosaurid Tylocephale;[26] and oviraptorids Conchoraptor, Heyuannia and Nemegtomaia.[27][28] Other taxa are represented by the large titanosaur Quaesitosaurus,[29] and a wide diversity of mammals and squamates.[30][31][32]

Bayan Mandahu Formation

editThe Bayan Mandahu Formation, which yielded Magnirostris (now synonym of Bagaceratops),[13] is considered to be Late Cretaceous in age, roughly Campanian. The dominant lithology is reddish-brown, poorly cemented, fine grained sandstone with some conglomerate, and caliche. Other facies include alluvial (stream-deposited) and aeolian (wind-deposited) sediments. It is likely that sediments at Bayan Mandahu were deposited by short-lived rivers and lakes on an alluvial plain with a combination of dune field paleoenvironments, under a semi-arid climate. The formation is known for its vertebrate fossils in life-like poses, most of which are preserved in unstructured sandstone, indicating a catastrophic rapid burial.[33][34]

This formation has produced numerous dinosaurs, such as closely related protoceratopsid Protoceratops;[35] ankylosaurid Pinacosaurus;[36][37] alvarezsaurid Linhenykus;[38] dromaeosaurids Linheraptor and Velociraptor;[39][40] oviraptorids Machairasaurus and Wulatelong;[41][42] and troodontids Linhevenator, Papiliovenator, and Philovenator.[43] Other paleofauna from this unit comprises a variety of squamates and mammals,[44][45] and nanhsiungchelyids turtles.[46]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Maryańska, T.; Osmólska, H. (1975). "Protoceratopsidae (Dinosauria) of Asia" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 33: 134−143.

- ^ Watabe, M., Suzuki, S., 2000a. Report on the Japan-Mongolia Joint Paleontological Expedition to the Gobi desert, 1993. Hayashibara Museum of Natural SciencesResearch Bulletin 1, 17 29.

- ^ Matsumoto, Y.; Saneyoshi, M. (2010). "Bored dinosaur skeletons". The Journal of the Geological Society of Japan. 116 (1): I–II. doi:10.5575/geosoc.116.1.I_II.

- ^ Saneyoshi, M.; Watabe, M.; Suzuki, S.; Tsogtbaatar, K. (2011). "Trace fossils on dinosaur bones from Upper Cretaceous eolian deposits in Mongolia: Taphonomic interpretation of paleoecosystems in ancient desert environments". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 311 (1–2): 38−47. Bibcode:2011PPP...311...38S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.07.024.

- ^ a b c Kim, B.; Yun, H.; Lee, Y.-N. (2019). "The postcranial skeleton of Bagaceratops (Ornithischia: Neoceratopsia) from the Baruungoyot Formation (Upper Cretaceous) in Hermiin Tsav of southwestern Gobi, Mongolia". Journal of the Geological Society of Korea. 55 (2): 179−190. doi:10.14770/jgsk.2019.55.2.179. S2CID 150321203.

- ^ Czepiński, Ł. (2020). "New protoceratopsid specimens improve the age correlation of the Upper Cretaceous Gobi Desert strata". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 65 (3): 481−497. doi:10.4202/app.00701.2019.

- ^ Kurzanov, S. M. (1990). "Новый род протоцератопсид из позднего мела Монголии" [A new Late Cretaceous protoceratopsid genus from Mongolia] (PDF). Paleontological Journal (in Russian) (4): 91−97.

- ^ Sereno, P. C. (2000). "The fossil record, systematics and evolution of pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians from Asia" (PDF). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 488–489.

- ^ Alifanov, V. R. (2003). "Two new dinosaurs of the infraorder Neoceratopsia (Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Nemegt Depression, Mongolian People's Republic". Paleontological Journal. 37 (5): 524–534.

- ^ You, H.; Dong, Z. (2003). "A New Protoceratopsid (Dinosauria: Neoceratopsia) from the Late Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia, China". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition). 77 (3): 299−303. Bibcode:2003AcGlS..77..299Y. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2003.tb00745.x.

- ^ Makovicky, P. J.; Norell, M. A. (2006). "Yamaceratops dorngobiensis, a New Primitive Ceratopsian (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Cretaceous of Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3530): 1–42. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2006)3530[1:YDANPC]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5808.

- ^ Alifanov, V. R. (2008). "The Tiny Horned Dinosaur Gobiceratops minutus gen. et sp. nov. (Bagaceratopidae, Neoceratopsia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". Paleontological Journal. 42 (6): 621–633. Bibcode:2008PalJ...42..621A. doi:10.1134/S0031030108060087. S2CID 129893753.

- ^ a b c d e f g Czepiński, Ł. (2019). "Ontogeny and variation of a protoceratopsid dinosaur Bagaceratops rozhdestvenskyi from the Late Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert". Historical Biology. 32 (10): 1394–1421. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1593404. S2CID 132780322.

- ^ Dodson, P. (1993). "Dinosaurs Rule The World". The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7853-0443-2.

- ^ Holtz, T. R.; Rey, L. V. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House. Supplementary Information 2012 Weight Information

- ^ a b Eberth, D. A. (2018). "Stratigraphy and paleoenvironmental evolution of the dinosaur-rich Baruungoyot-Nemegt succession (Upper Cretaceous), Nemegt Basin, southern Mongolia". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 494: 29–50. Bibcode:2018PPP...494...29E. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.11.018.

- ^ Gradziński, R.; Jerzykiewicz, T. (1974). "Sedimentation of the Barun Goyot Formation" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 30: 111−146.

- ^ Gradziński, R.; Jaworowska, Z. K.; Maryańska, T. (1977). "Upper Cretaceous Djadokhta, Barun Goyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia, including remarks on previous subdivisions". Acta Geologica Polonica. 27 (3): 281–326.

- ^ Arbour, V. M.; Currie, P. J.; Badamgarav, D. (2014). "The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 172 (3): 631−652. doi:10.1111/zoj.12185.

- ^ Park, J.-Y.; Lee, Y. N.; Currie, P. J.; Ryan, M. J.; Bell, P.; Sissons, R.; Koppelhus, E. B.; Barsbold, R.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H. (2021). "A new ankylosaurid skeleton from the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot Formation of Mongolia: its implications for ankylosaurid postcranial evolution". Scientific Reports. 11 (4101): 4101. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83568-4. PMC 7973727. PMID 33737515.

- ^ Averianov, A. O.; Lopatin, A. V. (2022). "A re-appraisal of Parvicursor remotus from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia: implications for the phylogeny and taxonomy of alvarezsaurid theropod dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 19 (16): 1097–1128. doi:10.1080/14772019.2021.2013965. S2CID 247222017.

- ^ Bell, A. K.; Chiappe, L. M.; Erickson, G. M.; Suzuki, S.; Watabe, M.; Barsbold, R.; Tsogtbaatar, K. (2010). "Description and ecologic analysis of Hollanda luceria, a Late Cretaceous bird from the Gobi Desert (Mongolia)". Cretaceous Research. 31 (1): 16−26. Bibcode:2010CrRes..31...16B. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.09.001.

- ^ Turner, A. H.; Montanari, S.; Norell, M. A. (2021). "A New Dromaeosaurid from the Late Cretaceous Khulsan Locality of Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3965): 1–48. doi:10.1206/3965.1. hdl:2246/7251. ISSN 0003-0082. S2CID 231597229.

- ^ Napoli, J. G.; Ruebenstahl, A. A.; Bhullar, B.-A. S.; Turner, A. H.; Norell, M. A. (2021). "A New Dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Coelurosauria) from Khulsan, Central Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3982): 1–47. doi:10.1206/3982.1. hdl:2246/7286. ISSN 0003-0082. S2CID 243849373.

- ^ Cau, A.; Madzia, D. (2018). "Redescription and affinities of Hulsanpes perlei (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". PeerJ. 6: e4868. doi:10.7717/peerj.4868. PMC 5978397. PMID 29868277.

- ^ Sullivan, R. M. (2006). "A taxonomic review of the Pachycephalosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin (35): 347–365.

- ^ Fanti, F.; Currie, P. J.; Badamgarav, D.; Lalueza-Fox, C. (2012). "New specimens of Nemegtomaia from the Baruungoyot and Nemegt Formations (Late Cretaceous) of Mongolia". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e31330. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731330F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031330. PMC 3275628. PMID 22347465.

- ^ Funston, G. F.; Mendonca, S. E.; Currie, P. J.; Barsbold, R.; Barsbold, R. (2018). "Oviraptorosaur anatomy, diversity and ecology in the Nemegt Basin". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 494: 101–120. Bibcode:2018PPP...494..101F. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.10.023.

- ^ Kurzanov, S. M.; Bannikov, A. F. (1983). "A new sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". Paleontological Journal. 2: 90−96.

- ^ Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. (1974). "Multituberculate succession in the Late Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert (Mongolia)" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 30: 23–44.

- ^ Gradziński, R.; Jerzykiewicz, T. (1974). "Dinosaur- and mammal-bearing aeolian and associated deposits of the Upper Cretaceous in the Gobi Desert (Mongolia)". Sedimentary Geology. 12 (4): 249–278. Bibcode:1974SedG...12..249G. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(74)90021-9.

- ^ Keqin, G.; Norell, M. A. (2000). "Taxonomic composition and systematics of late Cretaceous lizard assemblages from Ukhaa Tolgod and adjacent localities, Mongolian Gobi Desert". American Museum Novitates (249): 1−118. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2000)249<0001:TCASOL>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/1596. S2CID 129367764.

- ^ Jerzykiewicz, T.; Currie, P. J.; Eberth, D. A.; Johnston, P. A.; Koster, E. H.; Zheng, J.-J. (1993). "Djadokhta Formation correlative strata in Chinese Inner Mongolia: an overview of the stratigraphy, sedimentary geology, and paleontology and comparisons with the type locality in the pre-Altai Gobi". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10): 2180−2195. Bibcode:1993CaJES..30.2180J. doi:10.1139/e93-190.

- ^ Eberth, D. A. (1993). "Depositional environments and facies transitions of dinosaur-bearing Upper Cretaceous redbeds at Bayan Mandahu (Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10): 2196−2213. Bibcode:1993CaJES..30.2196E. doi:10.1139/e93-191.

- ^ Lambert, O.; Godefroit, P.; Li, H.; Shang, C.-Y.; Dong, Z. (2001). "A new Species of Protoceratops (Dinosauria, Neoceratopsia) from the Late Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia (P. R. China)" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre. 71: 5−28.

- ^ Godefroit, P.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X.; Li, H.; Dong, Z. M. (1999). "A new species of the ankylosaurid dinosaur Pinacosaurus from the Late Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia (P.R. China)" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre. 69 (supp. B): 17–36.

- ^ Currie, P. J.; Badamgarav, D.; Koppelhus, E. B.; Sissons, R.; Vickaryous, M. K. (2011). "Hands, feet and behaviour in Pinacosaurus (Dinosauria: Ankylosauridae)" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (3): 489–504. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0055. S2CID 129291148.

- ^ Xing, X.; Sullivan, Corwin; Pittman, M.; Choiniere, J. N.; Hone, D. W. E.; Upchurch, P.; Tan, Q.; Xiao, Dong; Lin, Tan; Han, F. (2011). "A monodactyl nonavian dinosaur and the complex evolution of the alvarezsauroid hand". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (6): 2338–2342. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.2338X. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011052108. PMC 3038769. PMID 21262806.

- ^ Godefroit, P.; Currie, P. J.; Li, H.; Shang, C. Y.; Dong, Z.-M. (2008). "A new species of Velociraptor (Dinosauria: Dromaeosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of northern China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (2): 432–438. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[432:ANSOVD]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 20490961. S2CID 129414074.

- ^ Xing, X.; Choinere, J. N.; Pittman, M.; Tan, Q. W.; Xiao, D.; Li, Z. Q.; Tan, L.; Clark, J. M.; Norell, M. A.; Hone, D. W. E; Sullivan, C. (2010). "A new dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Wulansuhai Formation of Inner Mongolia, China" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2403 (1): 1–9. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2403.1.1.

- ^ Longrich, N. R.; Currie, P. J.; Dong, Z. (2010). "A new oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia". Palaeontology. 53 (5): 945−960. Bibcode:2010Palgy..53..945L. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00968.x.

- ^ Xing, X.; Qing-Wei, T.; Shuo, W.; Sullivan, C.; Hone, D. W. E.; Feng-Lu, H.; Qing-Yu, M.; Lin, T.; Dong, T. (2013). "A new oviraptorid from the Upper Cretaceous of Nei Mongol,China, and its stratigraphic implications" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 51 (2): 85–101.

- ^ Pei, R.; Qin, Yuying; Wen, Aishu; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Guo, W.; Liu, P.; Ye, W.; Wang, L.; Yin, Z.; Dai, R.; Xu, X. (2022). "A new troodontid from the Upper Cretaceous Gobi Basin of inner Mongolia, China". Cretaceous Research. 130 (105052): 105052. Bibcode:2022CrRes.13005052P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105052. S2CID 244186762.

- ^ Gao, K.; Hou, L. (1996). "Systematics and taxonomic diversity of squamates from the Upper Cretaceous Djadochta Formation, Bayan Mandahu, Gobi Desert, People's Republic of China". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 33 (4): 578−598. Bibcode:1996CaJES..33..578G. doi:10.1139/e96-043.

- ^ Wible, J. R.; Shelley, S. L.; Bi, S. (2019). "New Genus and Species of Djadochtatheriid Multituberculate (Allotheria, Mammalia) from the Upper Cretaceous Bayan Mandahu Formation of Inner Mongolia". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 85 (4): 285–327. doi:10.2992/007.085.0401. S2CID 210840006.

- ^ Brinkman, D. B.; Tong, H.-Y.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.-S.; Godefroit, P.; Zhang, Z.-M. (2015). "New exceptionally well-preserved specimens of "Zangerlia" neimongolensis from Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia, and their taxonomic significance". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 14 (6–7): 577−587. Bibcode:2015CRPal..14..577B. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2014.12.005.