Bernard Charles Ecclestone (born 28 October 1930) is a British business magnate, motorsport executive and former racing driver. Widely known in journalism as the F1 Supremo,[a] Ecclestone founded the Formula One Group in 1987, controlling the commercial rights to Formula One until 2017.

Bernie Ecclestone | |

|---|---|

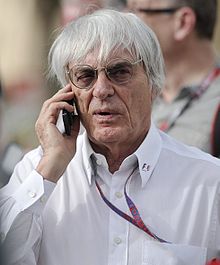

Ecclestone at the 2012 Bahrain Grand Prix | |

| Born | Bernard Charles Ecclestone 28 October 1930 St Peter South Elmham, Suffolk, England |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1950–present |

| Known for | Founder and CEO of the Formula One Group (1987–2017) |

| Spouses | Ivy Bamford

(m. 1952; div. 1967)Fabiana Flosi (m. 2012) |

| Children | 4, including Tamara and Petra[1][2] |

| Formula One World Championship career | |

| Nationality | |

| Active years | 1958 |

| Teams | Connaught |

| Entries | 2 (0 starts) |

| Championships | 0 |

| Wins | 0 |

| Podiums | 0 |

| Career points | 0 |

| Pole positions | 0 |

| Fastest laps | 0 |

| First entry | 1958 Monaco Grand Prix |

| Last entry | 1958 British Grand Prix |

Ecclestone began his career as a racing driver and entered two Grand Prix races during the 1958 season, but failed to qualify for either of them. Later, he became manager of drivers Stuart Lewis-Evans and Jochen Rindt. In 1972, he bought the Brabham team, which he ran for 15 years.[6] As a team owner he became a member of the Formula One Constructors Association, whom he led through the FISA–FOCA war. His control of the sport, which grew from his pioneering sale of the television rights in the late 1970s, was chiefly financial; under the terms of the Concorde Agreement, Ecclestone and his companies also controlled the administration, setup and logistics of each Grand Prix,[7] thus making him one of the richest men in the United Kingdom.[8] Ecclestone was replaced by Chase Carey as chief executive of the Formula One Group in 2017. He was subsequently appointed as chairman emeritus and acted as an adviser to the board.

Ecclestone and Flavio Briatore also owned the English football club Queens Park Rangers between 2007 and 2011.[9]

In October 2023, Ecclestone was convicted of tax fraud by false representation, and had to pay HM Revenue and Customs nearly £653m in back tax and penalties. He was sentenced to 17 months in prison, suspended for two years.

Early life

editEcclestone was born on 28 October 1930 in St Peter, South Elmham,[10] a hamlet three miles south of Bungay.[11][12] He was the son of Sidney Ecclestone, a fisherman, whose family was originally from Kent, and his wife Bertha Sophia (née Westley).[10] Ecclestone attended primary school in Wissett in Suffolk before the family moved to Danson Road,[13] Bexleyheath, southeast London, in 1938.[12] He was not evacuated to the countryside during the Second World War and remained with his family.[10]

Ecclestone left Dartford West Central Secondary School[10] at the age of 16 to work as an assistant in the chemical laboratory at the local gasworks[14] testing gas purity. He also studied chemistry at Woolwich Polytechnic[10] and pursued his hobby of motorcycles.

Motorsports career

editEarly career

editImmediately after the end of the Second World War, Ecclestone went into business trading in spare parts for motorcycles, and formed the Compton & Ecclestone motorcycle dealership with Fred Compton. His first racing experience came in 1949 in the 500cc Formula 3 Series, acquiring a Cooper Mk V in 1951.

He drove only a limited number of races, mainly at his local circuit, Brands Hatch, but achieved a number of good placings and an occasional win.[6] He initially retired from racing following several accidents at Brands Hatch, intending to focus on his business interests.[15]

Team ownership

editAfter his accident, Ecclestone temporarily left racing to make a number of eventually lucrative investments in property and loan financing and to manage the Weekend Car Auctions firm.

He returned to racing in 1957 as manager of driver Stuart Lewis-Evans, and purchased two chassis from the disbanded Connaught Formula One team. Ecclestone even tried, unsuccessfully, to qualify a car himself at Monaco in 1958, although this has since been described as "not a serious attempt".[16]

He also entered the British Grand Prix, but the car was raced by Jack Fairman.[17] He continued to manage Lewis-Evans when he moved to the Vanwall team; Roy Salvadori moved on to manage the Cooper team. Lewis-Evans suffered severe burns when his engine exploded at the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix and died six days later; Ecclestone was shocked and once again retired from racing.[18]

His friendship with Salvadori led to his becoming manager of driver Jochen Rindt[6] and a partial owner[19] of Rindt's 1970 Lotus Formula 2 team, whose other driver was Graham Hill. Rindt, on his way to the 1970 World Championship, died in a crash at the Monza circuit, though he was awarded the championship posthumously.[20]

Brabham

editDuring the 1971 season, Ecclestone was approached by Ron Tauranac, owner of the Brabham team, who was looking for a suitable business partner. Ecclestone made him an offer of £100,000 for the whole team, which Tauranac eventually accepted.[6] Tauranac stayed on as designer and to run the factory, while Colin Seeley was briefly brought in against Tauranac's wishes to assist in design and management.[21]

Ecclestone and Tauranac were both dominant personalities and Tauranac left Brabham early in the 1972 season. The team achieved little during 1972, as Ecclestone moulded the team to fit his vision of a Formula One team. He abandoned the highly successful customer car production business established by Jack Brabham and Tauranac – reasoning that to compete at the very front in Formula One you must concentrate all of your resources there. For the 1973 season, Ecclestone promoted Gordon Murray to chief designer. The young South African produced the triangular cross-section BT42, the first of a series of Ford-powered cars with which the Brabham team would take several victories in 1974 and 1975 with Carlos Reutemann and Carlos Pace.

Despite the increasing success of Murray's nimble Ford-powered cars, Ecclestone signed a deal with Alfa Romeo to use its powerful but heavy flat-12 engine from the 1976 season. Although this was financially beneficial, the new BT45s were unreliable and the Alfa engines rendered them significantly overweight. The 1976 and 1977 seasons saw Brabham fall towards the back of the field again, before winning two races again in the 1978 season when Ecclestone signed the Austrian double world champion Niki Lauda, intrigued by Murray's radical BT46 design.

The Brabham-Alfa era ended in 1979, the team's first season with the up-and-coming young Brazilian Nelson Piquet when Alfa Romeo started testing its own Formula One car during that season. This prompted Ecclestone to revert to Cosworth DFV engines – a move Murray described as "like having a holiday".

Piquet formed a close and long-lasting relationship with Ecclestone and the team, losing the title after a narrow battle with Alan Jones in 1980 and eventually winning in 1981 and 1983. In the summer of 1981 Brabham had tested a car powered by a BMW turbo engine, and 1982's new BT50 was powered by BMW's turbocharged four-cylinder M10. Brabham continued to run the Ford-powered BT49D in the early part of the season while reliability and driveability issues were sorted out by BMW and its technical partner Bosch. Ecclestone and BMW came close to splitting before the turbo car duly took its first win at the 1982 Canadian Grand Prix but the partnership took the first turbo-powered world championship in 1983.

The team continued to be competitive until 1985. At the end of the year, Piquet left after seven years. He was unhappy with the money that Ecclestone was willing to offer him and went to Williams where he would win his third championship. The following year, Murray, who since 1973 had designed cars that had scored 22 GP wins, left Brabham to join McLaren. Brabham continued under Ecclestone's leadership to the end of the 1987 season, in which the team scored only eight points. BMW withdrew from Formula One after the 1987 season.

Having bought the team from Ron Tauranac for approximately $120,000 at the end of 1971, Ecclestone eventually sold it for over US$5 million to a Swiss businessman, Joachim Luhti in 1988.[10]

Formula One executive

editIn parallel to his activities as team owner, Ecclestone formed the Formula One Constructors Association (FOCA) in 1974 with Frank Williams, Colin Chapman, Teddy Mayer, Ken Tyrrell, and Max Mosley. He became increasingly involved with his roles at FISA and the FOCA in the 1970s, in particular with negotiating the sport's television rights, in his decades-long advocacy for team control.[6]

Ecclestone became chief executive of FOCA in 1978 with Mosley as his legal adviser; together, they negotiated a series of legal issues with the FIA and Jean-Marie Balestre, culminating in Ecclestone's famous coup, his securing the right for FOCA to negotiate television contracts for the Grands Prix. For this purpose Ecclestone established Formula One Promotions and Administration, giving 47% of television revenues to teams, 30% to the FIA, and 23% to FOPA (i.e. Ecclestone himself); in return, FOPA put up the prize money – grand prix could literally be translated from French as "great prize".

Television rights shuffled between Ecclestone's companies, teams, and the FIA in the late 1990s, but Ecclestone emerged on top again in 1997 when he negotiated the fourth Concorde Agreement: in exchange for annual payments, he maintained the television rights.[22]

Also in 1978, Ecclestone hired Sid Watkins as official Formula One medical doctor. Following the crash at the 1978 Italian Grand Prix, Watkins demanded that Ecclestone provide better safety measures, which were provided at the next race. This way, Formula One began to improve safety, decreasing the number of deaths and serious injuries along the decades.[23]

At the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, following Ayrton Senna's fatal accident but while Senna was still alive, Ecclestone inadvertently misinformed Senna's family that Senna had died. Ecclestone had used a walkie-talkie to ask Sid Watkins - who was at the crash scene - about Senna's condition. Over the static of the walkie-talkie, Ecclestone misheard Watkins' response of "His head" as "He's dead". Based on this, Ecclestone told Senna's brother Leonardo, who was attending the race, that Senna had died. Senna in fact remained biologically alive for several more hours. This misunderstanding caused a rift in the hitherto friendly relations between Ecclestone and the Senna family; although Ecclestone travelled to Sâo Paulo at the time of Senna's funeral, he did not attend the funeral itself, instead watching it on television at his hotel.[24]

Despite heart surgery and triple coronary bypass in 1999, Ecclestone remained as energetic as always in promoting his own business interests.[25] In the late 1990s he reduced his share in SLEC Holdings (owner of the various F1 managing firms) to 25%, though despite his minority share he retained complete control of the companies.[26]

Ecclestone came under fire in October 2004 when he and British Racing Drivers' Club president Jackie Stewart were unable to come to terms regarding the future British Grand Prix, causing the race to be dropped from the 2005 provisional season calendar.[27] Negotiations with Ecclestone to keep the race in Formula One ended in the signing of a contract on 9 December to guarantee the continuation of the British Grand Prix for the following five years.[28] In mid-November 2004, the three banks comprising Speed Investments, which owns a 75% share in SLEC, which in turn controls Formula One – Bayerische Landesbank, J.P. Morgan Chase, and Lehman Brothers – sued Ecclestone for more control over the sport, prompting speculation that Ecclestone might altogether lose the control he had maintained for more than 30 years.[25][29]

A two-day hearing began on 23 November. After the proceedings ended the following day, Justice Andrew Park announced his intention to reserve ruling for several weeks. On 6 December 2004, Park read his verdict, stating that "In [his] judgment it is clear that Speed's contentions are correct and [he] should therefore make the declarations which it requests."[30] However, Ecclestone insisted that the verdict – seen almost universally as a legal blow to his control of Formula One – would mean "nothing at all".[31] He stated his intention to appeal against the decision. The following day, at a meeting of team bosses at Heathrow Airport in London, Ecclestone offered the teams a total of £260,000,000 over three years in return for unanimous renewal of the Concorde Agreement, which expired in 2008.[32] Two weeks later, Gerhard Gribkowsky, a board member of Bayerische Landesbank and the chairman of SLEC, said that the banks had no intention to remove Ecclestone from his position of control.[33]

Ecclestone saw 14 of 20 cars pull out of the 2005 United States Grand Prix at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The seven teams which refused to participate, stating concern over the safety of their Michelin tyres, requested rule changes and/or a change to the track configuration. Despite a series of meetings between Ecclestone, Max Mosley and the team principals, no compromise was reached by race time, and Ecclestone became an object of the public's frustration at the resultant six-car race. Despite him not having caused the problem, fans and journalists blamed him for failing to take control and enforce a solution, given the position of power in which he had placed himself.

On 25 November 2005 CVC Capital Partners announced it was to purchase both the Ecclestone shares of the Formula One Group (25% of SLEC) and Bayerische Landesbank's 48% share (held through Speed Investments).[34][35] This left Alpha Prema owning 71.65% of the Formula One Group.[36] Ecclestone used the proceeds of this sale to purchase a stake in this new company (the exact ratio of the CVC/Ecclestone shareholding is unknown). On 6 December Alpha Prema acquired JP Morgan's share of SLEC to increase its ownership of Formula One to 86%; the remaining 14% was held by Lehman Brothers.[37]

On 21 March 2006 the EU competition authorities approved the transaction subject to CVC selling Dorna, which controls the rights to MotoGP.[38] CVC announced the completion of the transaction on 28 March.[39] CVC acquired Lehman Brothers' share at the end of March 2006.[40] Allsport Management SA, owned by Paddy McNally was also acquired by CVC on 30 March.[41][42] On 21 July 2007, Ecclestone announced in the media that he would be open to discussing the purchase of Arsenal Football Club. As a close friend to former director of Arsenal David Dein, it was believed that the current board of the north London–based football club would prefer to sell to a British party, this after American-based investment company KSE headed by Stan Kroenke was thought to be preparing a £650 million takeover bid for Arsenal Holdings plc.[43]

The revenue sharing with the various teams, the Concorde Agreement, expired on the last day of 2007, and the contract with the FIA expired on the last day of 2012.

After the loss of Silverstone as the venue for the British Grand Prix in 2008, Ecclestone came under fire from several high-profile names for his handling of Formula One's revenues. Damon Hill blamed Formula One Management as a key factor in the loss of the event: "There's always been the question of the FOM fee, and ultimately that is the deciding factor. To quote Bernie, he once said: 'You can have anything you like, as long as you pay too much for it,' but we can't pay too much for something ... The problem is money goes out and away. There's a question whether that money even returns to Formula One."[44] Flavio Briatore also criticised FOM: "Nowadays Ecclestone takes 50% of all revenues, but we are supposed to be able to reduce our costs by 50%".[45]

Ecclestone was removed from his position as chief executive of Formula One Group on 23 January 2017, following its takeover by Liberty Media in 2016.[46]

Other activities

editIn 1996, Ecclestone's International Sportsworld Communicators signed a 14-year agreement with the FIA for the exclusive broadcasting rights for 18 FIA championships. In 1999, the European Commission investigated FIA, ISC and FOA for abusing dominant position and restricting competition.[47] As a result, in early 2000 the ISC and FIA made a new agreement to reduce the number of rights packages to two, the World Rally and Regional Rally Championships. In April 2000 Ecclestone sold ISC to a group led by David Richards.[48][49]

On 17 June 2005, Ecclestone made American headlines with his reply to a question about Danica Patrick's fourth-place finish at the Indianapolis 500, during an interview with Indianapolis television station WRTV: "She did a good job, didn't she? Super. Didn't think she'd be able to make it like that. You know, I've got one of these wonderful ideas that women should be all dressed in white like all the other domestic appliances." Following Patrick's 2008 victory at Twin Ring Motegi, Ecclestone personally sent her a congratulatory letter.[50]

On 7 January 2010, it was announced that Ecclestone had, together with Genii Capital, submitted a bid for Swedish car brand Saab Automobile.[51]

Queens Park Rangers

editOn 3 September 2007, it was announced that Ecclestone and Flavio Briatore had bought Queens Park Rangers (QPR) Football Club.[52] In December 2007, they were joined as co-owners by businessman Lakshmi Mittal, the fifth richest person in the world, who bought 20% of the club.[53]

On 17 December 2010 it was announced that Ecclestone had purchased the majority of shares from Flavio Briatore becoming the majority shareholder with 62% of the shares.[54] It was announced on 18 August 2011 that Ecclestone and Briatore had sold their entire shareholding in the club to Tony Fernandes, known for his ownership of the Caterham Formula 1 team.[9]

Controversies

editThis article's "criticism" or "controversy" section may compromise the article's neutrality. (March 2022) |

Great Train Robbery

editFor many years Ecclestone was rumoured to have been involved in the Great Train Robbery (1963). In a 2014 interview Ecclestone claimed that this rumour arose from his acquaintance with robber Roy James, the getaway driver who was an amateur racing driver. James later produced the silver trophy given to Formula One promoters.[55]

Labour Party controversy

editIn 1997, Ecclestone was involved in a political controversy over the British Labour Party's policy on tobacco sponsorship. Labour had pledged to ban tobacco advertising in its manifesto ahead of its 1997 general election victory, supporting a proposed European Union Directive banning tobacco advertising and sponsorship.[56] At this time all leading Formula One Teams carried significant branding from tobacco brands. The Labour Party's stance on banning tobacco advertising was reinforced following the general election by forceful statements from the Health Secretary Frank Dobson and Minister for Public Health Tessa Jowell.[57] Ecclestone appealed 'over Jowell's head' to Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair's chief of staff, who arranged a meeting with Blair. Ecclestone and Max Mosley, both Labour Party donors, met Blair on 16 October 1997, where Mosley argued:

"Motor racing was a world class industry which put Britain at the hi-tech edge. Deprived of tobacco money, Formula One would move abroad at the loss of 50,000 jobs, 150,000 part-time jobs and £900 million of exports."[57]

On 4 November the "fiercely anti-tobacco Jowell" argued in Brussels for an exemption for Formula One. Media attention initially focused on Labour bending its principles for a "glamour sport" and on the "false trail" of Jowell's husband's links to Benetton.[57] On 6 November correspondents from three newspapers inquired whether Labour had received any donations from Ecclestone; he had donated £1 million in January 1997. On 11 November Labour promised to return the money on the advice of Sir Patrick Neill.[58] On 17 November, Blair apologised for his government's mishandling of the affair and stated "the decision to exempt Formula One from tobacco sponsorship was taken two weeks later. It was in response to fears that Britain might lose the industry overseas to Asian countries who were bidding for it."[59] In 2008, the year after Blair stepped down as Prime Minister, internal Downing Street memos revealed that the decision had been made at the time of the meeting, and not two weeks later as Blair stated in Parliament.[60]

Tax avoidance (2008)

editInterviews conducted by a German prosecutor in the Gerhard Gribkowsky case showed that Ecclestone had been under investigation by the UK tax authorities for nine years, and that he had avoided the payment of £1.2 billion through a legal tax avoidance scheme. HM Revenue and Customs agreed to conclude the matter in 2008 with a payment of £10 million.[61]

Hitler remarks

editIn a Times interview published on 4 July 2009, Ecclestone said "terrible to say this I suppose, but apart from the fact that Hitler got taken away and persuaded to do things that I have no idea whether he wanted to do or not, he was – in the way that he could command a lot of people – able to get things done."[62] According to Ecclestone: "If you have a look at a democracy it hasn't done a lot of good for many countries — including this one", in reference to the United Kingdom.[62] He also said that his friend of 40 years Max Mosley, the son of British fascist leader Oswald Mosley, "would do a super job" as Prime Minister and added "I don't think his background would be a problem."[62]

Stephen Pollard, editor of The Jewish Chronicle, said: "Mr Ecclestone is either an idiot or morally repulsive. Either he has no idea how stupid and offensive his views are or he does and deserves to be held in contempt by all decent people."[63] In a subsequent interview with The Jewish Chronicle, Ecclestone said that his comments were taken the wrong way, but apologised, saying, "I'm just sorry that I was an idiot. I sincerely, genuinely apologise."[64] However, when Ecclestone was later told by Associated Press that the World Jewish Congress had called for his resignation, he said: "It's a pity they didn't sort the banks out," referring to the 2007–2008 financial crisis, and stated: "They have a lot of influence everywhere."[65]

Bribery accusation

editIn a 2012 trial against the former BayernLB chief risk officer Gerhard Gribkowsky, the public prosecutor accused Ecclestone of being a co-perpetrator in the case. Gribkowsky confessed to the charges of tax evasion, breach of trust and for accepting bribes. In closing arguments at a Munich trial the public prosecutor told the court Ecclestone "hasn't been blackmailed, he is a co-perpetrator in a bribery case". According to the prosecutor and defendant, Ecclestone paid about $44 million to the former banker to get rid of the lender's stake in Formula One. Ecclestone told prosecutors he paid Gribkowsky because he blackmailed him with telling UK tax authorities about a family trust controlled by Ecclestone's former wife.[66] In November 2012 private equity firm Bluewaters Communications Holdings filed a £409m lawsuit against the 2005 sale of Formula One, alleging it was the sport's rightful owner.[67]

In May 2013, Süddeutsche Zeitung reported that the Munich prosecutors' office had charged Ecclestone on two counts of bribery after a two-year investigation into his relationship with Gribkowsky.[68] In July 2013, German prosecutors indicted Ecclestone for alleged bribery. The charge relates to a $44 million (£29m) payment to Gribkowsky. It was linked to the sale of a stake in Formula 1.[69] Gribkowsky, the BayernLB bank executive, was found guilty of taking $44m in bribes and failing to pay tax on the money.[70]

On 14 January 2014, a court in Munich ruled that Ecclestone would indeed be tried on bribery charges in Germany,[71] and on 5 August 2014, the same court ruled that Ecclestone could pay a £60m settlement, without admitting guilt, to end the trial.[72]

Comments on diversity and racism

editIn the weeks following the events of the murder of George Floyd, seven-time world champion Lewis Hamilton, F1's only black driver, had launched his own commission to tackle racism and increase diversity, with Formula One launching a We Race As One initiative to fight global inequality. In an interview with CNN, Ecclestone initially praised Hamilton's efforts but then questioned whether it would "do anything bad or good for Formula One", before saying that "In a lot of cases, black people are more racist than what white people are."[73] In response, Hamilton has countered Ecclestone, criticising him on Instagram for being "ignorant and uneducated", and that he has realised why nothing much has been done to address diversity and racism.[74][75] Formula One Group also issued a statement, saying that they "completely disagree with Bernie Ecclestone's comments that have no place in Formula 1 or society", and had added that his title as a chairman emeritus had since expired in January 2020.[76]

Illegal possession of a firearm

editEcclestone was arrested by Brazilian authorities on 25 May 2022 for illegally carrying a firearm while boarding a private plane to Switzerland. An undocumented LW Seecamp .32 gun was found in his luggage during an x-ray screening. Ecclestone acknowledged owning the gun, but said he was unaware it was in his luggage at the time. He subsequently paid bail and was freed to travel to Switzerland.[77]

Comments on the Russian invasion of Ukraine

editOn 30 June 2022 Ecclestone appeared on an interview on ITV's Good Morning Britain. Co-host Kate Garraway asked if Ecclestone was "still a friend" of Vladimir Putin, to which he replied that he would "take a bullet" for him because he was a "first class person."[78] Ecclestone argued that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was just a "mistake" that all business men make. Ecclestone then went on to mention that he believed President Zelenskyy could have prevented the invasion of Ukraine.[79] GMB's other co-host Ben Shephard asked about the death of innocent Ukrainian citizens, to which Ecclestone said it was not "intentional" and gave examples of American invasions into other countries.

In the same interview, Ecclestone argued against the ban on Russian drivers taking part in Formula One. He suggested that he would not have removed the Russian Grand Prix or banned Russian drivers had he been a part of the decision-making process.[80][better source needed] In response, Formula One released a statement that said: "The comments made by Bernie Ecclestone are his personal views and are in very stark contrast to position of the modern values of the sport."[81]

Tax fraud

editOn 11 July 2022 Ecclestone was officially charged with tax fraud ("fraud by false representation") by the Crown Prosecution Service after an examination of a file sent to the CPS by HM Revenue and Customs which reported he had failed to declare foreign assets of £400 million.[82]

The first hearing into the case was scheduled for 22 August at Westminster Magistrates' Court.[83] In January 2023 the trial date was pushed back to November 2023 at an administrative hearing at Southwark Crown Court.[84]

On 12 October 2023 at Southwark Crown Court Ecclestone pleaded guilty to fraud, after agreeing to pay nearly £653m in back tax and fines. He was sentenced to 17 months in prison, suspended for two years.[85]

Tom Bower biography

editIn 2011, Faber and Faber published Tom Bower's biography No Angel: The Secret Life of Bernie Ecclestone, which was written with Ecclestone's co-operation. Bower's previous exposé biographies of figures such as Robert Maxwell led commentators such as Bryan Appleyard, writing for the New Statesman, to express surprise over Ecclestone's co-operation.[86]

The book recounts an episode at the 1979 Argentine Grand Prix in which Colin Chapman offered Mario Andretti $1000 to push Ecclestone into a hotel swimming pool in Buenos Aires. A nervous Andretti approached Ecclestone and confessed the plot, to which Ecclestone replied: "Pay me half and you can".[87]

Personal life

editAs of February 2024, Forbes World's Billionaires List estimated Ecclestone's net worth at $2.9 billion.[88] In early 2004, he sold one of his London residences in Kensington Palace Gardens, never having lived in it, to Indian steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal for £57.1 million.[89] At Grand Prix venues, Ecclestone used a grey mobile home, known as "Bernie's bus", as his headquarters.[90] In 2005, Ecclestone sold his £9 million yacht Va Bene to his friend Eric Clapton. Terry Lovell published a biography of Ecclestone, Bernie's Game: Inside the Formula One World of Bernie Ecclestone in March 2003 after legal issues had delayed its publication from its original date of November 2001.[91] Ecclestone turned down a knighthood in the early 2000s as he did not believe that he deserved it. In a 2019 interview, he stated that if he had brought some good to the country, he was glad, but he did not set out with this purpose in mind, so did not deserve recognition.[24]

Ecclestone has been married three times. With first wife Ivy, he has a daughter, Deborah, through whom he is a great-grandfather. He has five grandchildren — two granddaughters and three grandsons.[92] Ecclestone had a 17-year relationship with Tuana Tan, which ended in 1984 when Slavica Radić, later his second wife, became pregnant.[93] Ecclestone was then married to Yugoslav-born former Armani model Radić for 23 years.[94] The couple have two daughters, Tamara (born 1984) and Petra (born 1988). In 2008, Slavica Ecclestone filed for divorce.[95] Slavica settled their divorce amicably with her receiving a reported $1 billion to $1.5 billion settlement.[96] The divorce was granted on 11 March 2009.[97] In August 2012 Ecclestone married Fabiana Flosi, the vice-president of marketing for the Brazilian Grand Prix.[98] Flosi is 46 years younger than Ecclestone.[99] Ecclestone's son with Flosi was born in July 2020.[100][101] He is one of the oldest known fathers.

Complete Formula One World Championship results

edit(key)

| Year | Entrant | Chassis | Engine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | WDC | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | B C Ecclestone | Connaught Type B | Alta Straight-4 | ARG | MON DNQ |

NED | 500 | BEL | FRA | GBR DNP |

GER | POR | ITA | MOR | NC | 0 |

Awards and honours

edit- 2000 Grand Decoration of Honour in Gold for Services to the Republic of Austria[104]

- 2006 Commander of the Order of Saint-Charles, Monaco[105]

- 2008 Imperial College Honorary Doctorate[106]

Notes

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone: A Short History of F1's Billion-Dollar Brain". Bleacher Report. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Home of the Daily and Sunday Express | Express Yourself :: Fast life of billionaire Bernie Ecclestone". Daily Express. 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Weaver, Paul (15 May 2013). "Bernie Ecclestone F1 future under cloud as bribery charges are prepared". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Mark Webber v Sebastian Vettel clash: F1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone unhappy with Red Bull's tactics". The Independent. London. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Bervanakis, Maria (23 January 2012). "The fast life of 'F1 Supremo' Bernie Ecclestone". News Limited Network. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Tremayne, David (1996). Formula One: A Complete Race by Race Guide (1st ed.). Avonmouth, Bristol, United Kingdom: Parragon Book Service. p. 8. ISBN 0-7525-1762-7. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Grand prix, grand prizes". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone net worth — Sunday Times Rich List 2021". The Sunday Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Malaysian executive buys QPR from Ecclestone". The Washington Times. 18 August 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Bower, Tom (2011). No Angel: The Secret Life of Bernie Ecclestone. Faber and Faber. pp. 11–15. ISBN 9780571269365.

- ^ Cary, Tom (28 October 2010). "Bernie Ecclestone at 80: timeline". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ a b Poor Suffolk boy to Formula One billionaire Archived 10 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Eastern Daily Press, 3 March 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Surnames beginning with E". bexley.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Bernie Ecclestone Biography at Grand Prix.com.. Retrieved 10 February 2014

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone – F1 Driver Profile". ESPN. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Lovell, Terry (2009). Bernie Ecclestone: King of Sport. London: John Blake. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-84454-826-2.

- ^ Small, Steve (1994). The Guinness Complete Grand Prix Who's Who. Enfield: Guinness Publishing. p. 411. ISBN 0-85112-702-9.

- ^ Sylt, Christian (10 November 2013). "Bernie Ecclestone signs $600 million Formula One deal". Autoweek. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "8W – Who – Graham Hill". Autosport. 10 June 2002. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ O'Keefe, Thomas C. (6 October 1999). "Formula Bernie (Tobacco + TV + Tracks = $2 Billion)". Atlas F1. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Lawrence (1999) p. 116 Tauranac claims that Ecclestone initially offered £130,000, but lowered the offer at the last minute. Ecclestone denies that this happened. Lovell (2004) pp.32–33

- ^ Henry, Alan (2003). The Power Brokers: The Battle for F1's Billions. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-61059-216-1.

- ^ Garrett, Jerry (1 October 2002). "Dr. Watkins, Guardian Angel". Car and Driver. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ a b "MUST-LISTEN: Bernie Ecclestone guests on F1's official podcast". www.formula1.com. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ a b Edmondson, Lawrence (27 October 2010). "Ecclestone at 80: Bernie Ecclestone timeline". ESPN. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Saward, Joe (7 March 2002). "Who owns what in Formula 1?". GrandPrix.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2002. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Tremayne, David (1 October 2004). "Stewart in plea to Ecclestone after British Grand Prix is axed". The Independent. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Silverstone seals British GP deal". BBC Sport. 9 December 2004. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Henry, Alan (23 November 2004). "Ecclestone faces his greatest challenge for control". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Legal blow for Ecclestone". ITV F1. 7 December 2004. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Bernie defiant". ITV F1. 6 December 2004. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Bernie offers £260m payday". ITV F1. 7 December 2004. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Ecclestone to remain in charge". ITV F1. 22 December 2004. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ Downes, Steven (25 November 2005). "Ecclestone sells F1 stake for £1bn". The Times. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Duff, Alex (25 November 2005). "Ecclestone Sells Part of Formula One Stake to CVC". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "JP Morgan sells out". GrandPrix.com. 6 December 2005. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Wallop, Harry (7 December 2005). "CVC moves into F1 driving seat". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Noble, Jonathan (21 March 2006). "CVC gets EU approval; must sell MotoGP". Autosport. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Olson, Penny (28 March 2006). "CVC Gets Into Gear With Ecclestone's F1 Stake". Forbes. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "CVC buys Lehman Brothers' F1 shares". Autosport. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "CVC acquires Allsport". www.autosport.com. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Rights holders CVC buy further into Formula One". Times of Malta. 2 April 2006. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Mossop, James (22 July 2007). "Bernie Ecclestone to fight American Stan Kroenke for control of Arsenal". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "Hill blames F1's economy for losing GP". Autosport. 4 July 2008.

- ^ "Briatore says F1 needs an overhaul". Autosport. 29 July 2008.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (23 January 2017). "Bernie Ecclestone removed as Liberty Media completes $8bn takeover". BBC Sport. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Brussels accuses F1 motor racing of abusing its dominant position - The Irish Times, 30 June 1999

- ^ "Richards gets rallying". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 17 April 2000.

- ^ "Ecclestone sells rally rights". Crash. 11 April 2000. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ McEntegart, Pete (20 June 2005). "The 10 Spot: 20 June 2005". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 29 August 2005. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

6. Formula One's planned invasion of the U.S. market will have to wait a few years...

- ^ "Genii team up with Bernie Ecclestone to bid for Saab Automobile". Saabs United. 8 January 2010. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ "CLUB STATEMENT". Queens Park Rangers F.C. 3 September 2007. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Lakshmi Mittal invests in QPR". 20 December 2007. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone is now majority shareholder of Queens Park Rangers". The Guardian. London. 17 December 2010. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ Benson, Andrew. "BBC Sport – Bernie Ecclestone – the man, the myths and the motors". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Timeline: Smoking and disease". BBC News. 30 June 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ a b c Rawnsley, Andrew (2001). Servants of The People. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-027850-8.

- ^ "How the Ecclestone affair unfolded". BBC News. 22 September 2000. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ "Blair apologises for mishandling F1 row". BBC News. 17 November 1997. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ Oliver, Jonathan; Oakeshott, Isabel (12 October 2008). "Secret papers reveal Tony Blair's F1 tobacco deal". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Darragh, MacIntyre (28 April 2014). "F1's Ecclestone avoided potential £1.2bn tax bill". BBC News. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Alice Thomson and Rachel Sylvester "Bernie Ecclestone, the Formula One boss, says despots are underrated", The Times, 4 July 2009; (archived version)

- ^ Steve Bird, Ruth Gledhill and Sam Coates "Hitler? He got things done, says Formula One chief Bernie Ecclestone", The Times, 4 July 2009

- ^ Simon Rocker "Ecclestone: I was an idiot over Hitler", The Jewish Chronicle, 6 July 2009

- ^ Associated Press "Ecclestone says he won't resign over Hitler remarks", USA Today, 6 July 2009

- ^ Oliver Suess "Ecclestone 'Co-Perpetrator' in Bribery, Prosecutor Says", Bloomberg BusinessWeek, 27 June 2012

- ^ "£409m lawsuit against Ecclestone and CVC revealed". Pitpass.com. 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone: Formula 1 boss reportedly facing charges". BBC News. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ "Formula 1 boss Ecclestone indicted". BBC. 17 July 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Bernie Ecclestone indicted by German court for alleged bribery Guardian 17 July 2013

- ^ "Formula 1: Ecclestone to face Germany bribery charges". BBC News. 16 January 2014.

- ^ "F1 boss Ecclestone pays to end bribery trial". BBC News. 5 August 2014.

- ^ Amanda Davies; George Ramsay (26 June 2020). "Often 'Black people are more racist than White people,' says ex-F1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone". CNN. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Ecclestone comments ignorant - Hamilton". BBC Sport. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Hamilton: Lack of F1 diversity under Ecclestone makes 'sense'". www.motorsport.com. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "F1 issues statement following recent comments made by Bernie Ecclestone". www.formula1.com. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone: Former F1 CEO arrested in Brazil for illegally carrying a gun". Sky Sports. 26 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Jackson, Siba (30 June 2022). "Bernie Ecclestone says he would 'take a bullet' for 'first class' Vladimir Putin as he defends war in Ukraine". Sky News. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Simone, Carlo (30 June 2022). "GMB fans react to Bernie Ecclestone's praise of Vladimir Putin". Telegraph & Argus. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Llewellyn, Liam (30 June 2022). "Bernie Ecclestone wants Russian drivers back in F1 amid Vladimir Putin defence". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Noble, Jonathon (30 June 2022). "F1 hits out at Bernie Ecclestone's Putin defence". au.motorsport.com. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Chappell, Peter (11 July 2022). "Bernie Ecclestone charged with tax fraud". The Times. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Jolly, Jasper (11 July 2022). "Bernie Ecclestone charged with fraud over £400m assets". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone in court ahead of fraud trial for 'failing to declare £400m worth of assets held overseas'". uk.finance.yahoo.com. 20 January 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone pleads guilty to fraud". BBC News. 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Appleyard, Bryan (27 April 2011). "No Angel: The Secret Life of Bernie Ecclestone". New Statesman. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Bower, Tom (2011). No Angel: The Secret Life of Bernie Ecclestone. Faber and Faber. p. 98. ISBN 9780571269365.

- ^ "Bernard Ecclestone & family". Forbes. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Most-Expensive.net, 28 January 2009 Archived 1 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Daily Telegraph. "Bernie Ecclestone: Interview". Ukmotorsport.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ Green, Andrew (28 February 2003). "Formula One: Playing Bernie's game". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Ahmed, Murad (24 November 2017). "Bernie Ecclestone on mischief-making and why Putin should run Europe". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ Bower, Tom (2012). No Angel: The Secret Life of Bernie Ecclestone. Faber & Faber. p. 133. ISBN 9780571269365.

- ^ Lovell (2004) p.345

- ^ Quinn, Ben (21 November 2008). "Bernie Ecclestone wife in line for big divorce payout". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ The 5 Most Expensive Divorces [Gastelum Law], |3 December 2014

- ^ F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone's Divorce Finalized, 11 March 2009

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone, 89, Welcomes 4th Child, His 1st With Fabiana Flosi, 44". Us Weekly. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ "Formula One boss's daughter won't go to his wedding". Independent. 29 May 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "Former Formula 1 Chief Bernie Ecclestone, 89, Welcomes Son with Wife Fabiana Flosi, 44". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone to become a father for fourth time at 89". Independent. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Bernie Ecclestone". Motor Sport. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Carter, Ben (2 March 2011). "Bernie Ecclestone's shower of madness". The Roar. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "staatliche Auszeichnungen bis 2012" (PDF). Sportsektion des Bundesministeriums für Landesverteidigung und Sport. 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Nomination by Sovereign Ordonnance Archived 15 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine n° 528 of 27 May 2006 (French)

- ^ "Imperial awards honorary degrees to leading figures in business and academia". Imperial College. 14 May 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

Bibliography

edit- Bernie Ecclestone, the man behind Formula One BBC News, 12 November 1997

- Chicanery in Formula One? The Economist, 26 August 2004

- Grand prix, grand prizes. The Economist, 13 July 2004

- Griffiths, John The case that will decide Formula One's future. Financial Times, 23 November 2004

- Lovell, Terry (2004). Bernie's Game. Metro Books. ISBN 1-84358-086-1.

- Mott, Sue The funny billionaire in trapped in the body of a tyrant Telegraph, 20 March 2004

- Mr Formula One The Economist, 13 March 1997

- The main men in F1 BBC Sport, 11 October 2004

- The Governor of Grand Prix UK Motorsport, from Daily Telegraph, 1997

External links

edit- Bernie Ecclestone at IMDb

- #212 Bernard Ecclestone & Family at Forbes Billionaires, 2010, 10 March 2010

- Bernie Ecclestone collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Bernie Ecclestone collected news and commentary at The New York Times