The Banda people are an ethnic group of the Central African Republic. They are likewise found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, and South Sudan.[1] They were severely affected by slave raids of the 19th century and slave trading out of Africa.[2][3][4] Under French colonial rule, most converted to Christianity but retained elements of their traditional religious systems and values.[5]

Banda | |

|---|---|

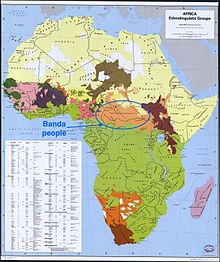

The approximate geographical distribution of Banda people[1] | |

| Total population | |

| Over 1 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Religion | |

| Catholicism Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Gbaya people, Ngbandi people, African-Americans, Afro-Brazilians, other people of the African diaspora |

Demographics

editEstimated to be around 1.3 million people at the turn of the 21st century, they constitute one of the largest ethnic groups in the Central African Republic, traditionally found in the northeastern part of the country.[2][5][6]

The Banda people speak languages belonging to the Niger-Congo family,[7] known as Banda or Ubangian languages.[1][6] The Banda languages have variations; nine distinct geographically distributed vernaculars are known.[8]

Slavery

editThe Banda people were severely affected by slave raids from the north, particularly from Wadai and Darfur, in the early 19th century, and later by Khartoumers led by al-Zubayr. These captured and sold the Banda people into slavery. Many migrated south and west along the Ubangi River.[2][3]

According to Ann Brower Stahl, a professor of Anthropology specializing in Africa studies, the medieval towns of Banda people such as Begho were probably a source of slaves between 1400 and 1600 CE, with slaves going to Islamic North Africa, the primary trade being in women and children before 1500 CE.[9] By the 16th century, slaves from the Banda regions were in use as production labor in Sudanese Islamic states, and this trade in slaves remained fairly steady in the centuries that followed.[9] Dennis Cordell, a professor of History specializing on Africa, places the slave raiding and trade practices earlier to the 11th- and 12th-century raids in southern Libya, then to Lake Chad area, which he states thereafter expanded south into the Banda people's region.[10]

The killing, enslavement and carrying away of the Banda people by slave raiders from regions that are now part of Chad, South Sudan and southeastern Central African Republic led to their depopulation, a situation further worsened when European colonialists gave weapons to the slave-raiding states.[11] In the late 19th century, they were raided by "slave hunters" from the south by armies of the Zande states now part of Congo and South Sudan, led by Arab traders who had set up Zariba (slave trading centers).[2][3][4] The slave raiding of the Banda people was suppressed when the French Ubangi-Shari colony was established in this region.[11]

According to American history professor Richard Bradshaw, the Banda people along with their neighbors, the Gbaya people, lived a generally peaceful life before the 19th century, after which Kevin Shillington states "African slave traders and then European colonialists introduced unprecedented violence and economic exploitation into their lives".[2] Greek social anthropology professor G. P. Makris states that the Banda people, along with the Nuba and Gumuz ethnic groups, were also a major victim of slave trading by Turco-Egyptians.

Society

editStructure

editThe Banda are a patrilineal ethnic group, who traditionally have lived in the Savannas north of the Congo, in dispersed home groups guided by a headman.[2] They sustain themselves by hunting, fishing, gathering wild foods and growing crops.[1] During times of crisis, to resist slave raids and to respond to wars, the Banda selected war chiefs. After the crisis was over, they relieved their warriors of their powers.[1]

Culture

editThe ethnic group is locally famous for craftsmanship, specifically carved wooden objects used for rituals and general utility, as well as their large animal-shaped slit drums.[1] These drums, now attributed by various names such as Banda-Yangere,[12] were used by the Banda people for musical celebrations and as tools for transmitting messages.[13] The Banda-Linda group is known for their music using wooden pipes, also called Banda-Linda Horns.

In contemporary times, the Banda people are settled farmers in the Savannas.[14] Cotton and cassava farming was promoted among the Banda people by the French colonial officials, while Christian missionaries won many converts during the French rule.[5] Most Banda people are now Protestants (52%) or Catholic (38%). However, they have retained many of their traditional beliefs alongside those of Christianity, such as making sacrificial offerings to ancestral spirits for seasonal success for crops.[5]

The Banda people have their rites of passage, such as Semali which recognizes the crossing into adulthood. At weddings, dowries in the form of bridewealth have traditionally included iron implements for the family.[7] Polygyny was practiced historically among the Banda people, but this practice has declined in modern times.[1]

Notable People

edit- Ginette Amara, former Minister of Scientific Research and Technological Innovation

- Sonny M'Pokomandji, Central African basketball player

- Henri Pouzère, Central African politician and lawyer.[15]

- Marie Solange Pagonendji-Ndakala, former minister of tourism and social affairs

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Banda (people)

- ^ a b c d e f Kevin Shillington (2013). Encyclopedia of African History. Routledge. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-1-135-45670-2.

- ^ a b c Richard Bradshaw; Juan Fandos-Rius (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-8108-7992-8.

- ^ a b Sylviane A. Diouf (2003). Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies. Ohio University Press. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-0-8214-4180-0.

- ^ a b c d Richard Bradshaw; Juan Fandos-Rius (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-8108-7992-8.

- ^ a b Robert C. Mitchell; Donald G. Morrison; John N. Paden (1989). Black Africa: A Comparative Handbook. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 404–405. ISBN 978-1-349-11023-0.

- ^ a b Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- ^ Toyin Falola; Daniel Jean-Jacques (2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-59884-666-9.

- ^ a b Ann Brower Stahl (2001). Making History in Banda: Anthropological Visions of Africa's Past. Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–88, 23–24. ISBN 978-1-139-42886-6.

- ^ Dennis Cordell (2003). Sylviane A. Diouf (ed.). Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies. Ohio University Press. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-0-8214-1517-7.

- ^ a b Richard Bradshaw; Juan Fandos-Rius (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8108-7992-8., Quote: "During the 19th century, slave raiders from what are now Chad, South Sudan and southeastern CAR began to penetrate Banda territory and killed or carried away many of its inhabitants. The arrival of European colonialists at the turn of the 20th century initially provided slave-raiding states with more weapons and this contributed to the depopulation of much of eastern CAR, but the French suppressed slave raiding once they established the colony of Ubangi-Shari. By this time, however, many Banda communities in eastern CAR had disappeared altogether."

- ^ Library of Congress, United States (2010). "Yangere (African people), Variants: Banda-Yangere (African people), Yanguere". LOC Linked Data Service. Retrieved 2016-10-19.

- ^ Toyin Falola; Daniel Jean-Jacques (2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-59884-666-9.

- ^ Jacqueline Cassandra Woodfork (2006). Culture and Customs of the Central African Republic. Greenwood. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-313-33203-6.

- ^ Bradshaw, Richard; Rius, Juan Fandos (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic (Historical Dictionaries of Africa). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 528.