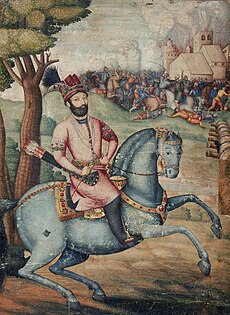

Emperor Nader Shah, the Shah of Iran (1736–1747) and the founder of the Afsharid dynasty, invaded Northern India, eventually attacking Delhi in March 1739. His army had easily defeated the Mughals at the Battle of Karnal and would eventually capture the Mughal capital in the aftermath of the battle.[4]

| Invasion of Northern India | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Naderian Wars | |||||||||

Representation of Nader Shah at the sack of Delhi | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

Nader Shah's victory against the weak and crumbling Mughal Empire in the far east meant that he could afford to turn back and resume war against Persia's archrival, the neighbouring Ottoman Empire, but also the further campaigns in the North Caucasus and Central Asia.[5]

The loss of the Mughal treasury, which was carried back to Persia, dealt the final blow to the effective power of the Mughal Empire in India.

Prelude

editBy the end of 1736, Nader Shah had consolidated his rule over Iran and dealt with the internal uprisings that had developed over the three years before that. He now shifted his focus towards the Afghan Ghilji tribe, who had been reorganised by their new leader Hussain Hotak (r. 1725–1738), a cousin of Ashraf Hotak. By the middle of the 1730s, Hussain Hotak had built up a substantial power base as the ruler of Herat and had been striving for some years to weaken Nader Shah's authority over present-day Afghanistan. By April 1737, Nader Shah had gone east and established his camp at a location close to the city Kandahar, where he ordered the construction of a city named Naderabad. He soon defeated Hussain Khan and captured Kandahar, thus putting an end to the Ghilji tribe's dominance.[6] On 21 May 1738, Nader Shah left Naderabad and marched towards the city of Kabul. On 11 June, he reached Ghazni after crossing the traditional border between Iran and the Mughal Empire.[7]

At first, Nader Shah told the Mughals that he had no issues with them and he only moved into their domain to look for runaway Afghans.[8] According to some contemporary Indian sources, the Mughal vassals plotting to weaken the authority of their suzerain were the reason behind Nader Shah's invasion of the Indian subcontinent. According to the Iranologist Laurence Lockhart, Nader Shah understood that he could fund his aspirations of expansion "with the spoils of India" because "the almost continual campaigns of the past few years had caused famine in Persia and brought her to the verge of bankruptcy." However, another Iranologist, Ernest S. Tucker, argues that "Long before the 1730s, though, Iran had already been in a state of financial crisis, partly because of the continued steady decline in Iranian exports that had caused a substantial reduction in state revenues."[9] According to the Iranologist Michael Axworthy, the aim of the invasion was because Nader Shah "needed a breathing space, for the country to recover, and a new source of cash to pay the army, before he renewed his attack on the Ottomans."[10]

By the start of the 18th century, the Mughals were struggling with a number of political issues. India started to fragment after the death of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, eventually becoming a collection of kingdoms ruled by individuals who claimed nominal allegiance to the Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah (r. 1719–1748), but essentially acted as independent rulers. Another political danger was the expansion of the Maratha Confederacy under Bajirao I. By challenging long-held beliefs about the necessity of Muslim political power in India, the Marathas presented a unique challenge to Mughal rule. By the beginning of the 18th century, the Indian subcontinent was still a huge and prosperous agricultural economy, but becoming more and more divided , making it an alluring target for a conqueror short on finance.[9]

Invasions

editNader Shah crossed Mughal territory at the Mukhur spring and halted at Qarabagh, south of Ghazni. A detachment was sent under Nader's son, Nasrullah, to attack the Afghans of Ghorband and Bamian.[11] When the governor of Ghazni fled upon hearing of Nader's approach, the Qadi, scholars and rich men of Ghazni gave the invaders presents and submitted to Nader when he entered on 31 May.[11] Meanwhile, the other detachment had defeated the Afghans, pardoning all who surrendered, and exacting cruel punishment on those who resisted.

With his flank secure, Nader was free to march on Kabul. The chief men of the city tried to give in peacefully, but Sharza Khan decided to give resistance. On 10 June, Nader reached the city and the garrison sallied out to try and attack the Persians, who then just retreated to a safe distance where they could besiege the city. Nader arrived on the 11th and surveyed the city's defences from atop the Black Rock.[11] The garrison tried to attack again, but were driven out by the Persian Army. The city was besieged for a week until on 19 June, the tower of Aqa-bin collapsed, and the citadel capitulated.

Nader settled down in Kabul to handle the province's affairs. He received word that the Mughal Emperor would not receive Nader's letter to him, nor would he let his ambassador leave. In response, he sent an envoy to the imperial court, and expressed that his only wish was to do the Mughals a favour and rid them of the Afghans; how they had done more damage to India, and that the Kabul garrison's hostility forced him to fight them. The envoy sent to deliver the letter was turned back at Jalalabad, and then murdered by a neighbouring chieftain.[11]

While this was going on, Nader left Kabul due to lack of supplies and started for Gandamak on 25 August. The Afsharid force reached Jalalabad and sacked the city on 7 September in revenge for the murder of Nader's courier. Nader sent his son, Reza to Iran (3 November).

Conquest of Punjab

editOn 6 November, the march through India was resumed. Nasir Khan, the Mughal governor of Kabul Subah, was in Peshawar when he heard of Nader Shah's invasion. He hastily assembled some 20,000 poorly-trained tribal levies that would be no match for Nader's veteran soldiery. Nader marched swiftly through the steep path and outflanked the Mughal army at the Khyber Pass and annihilated it. Three days after the battle, Nader occupied Peshawar without resistance.

On 12 December, they resumed marching. They built a bridge over the Indus river by Attock and crossed the Chenab near Wazirabad on 8 January 1739. In the Battle of Karnal on 24 February 1739, Nader led his army to victory over the Mughals. Muhammad Shah surrendered and both entered Delhi together.[12] The keys to the capital of Delhi were surrendered to Nader. He entered the city on 20 March 1739. The next day, Nader Shah held a durbar in Delhi.

Massacre of Delhi

editThe Afsharid occupation led to price increases in the city. The city administrator attempted to fix prices at a lower level and Afsharid troops were sent to the market at Paharganj, Delhi to enforce them. However, the local merchants refused to accept the lower prices and this resulted in violence during which some Afsharid troops were assaulted and killed.

When a rumour spread that Nader had been assassinated by a female guard at the Red Fort, some Indians attacked and killed 3,000 Afsharid troops during the riots that broke out on the night of 21 March.[13] Nader, furious at the killings, retaliated by ordering his soldiers to carry out the notorious qatl-e-aam (massacre – qatl = killing, aam = common public, in open) of Delhi.

On the morning of 22 March, Nader Shah sat at Sunehri Masjid of Roshan-ud-Daulah. He then, to the accompaniment of the rolling of drums and the blaring of trumpets, unsheathed his great battle sword in a grand flourish to the great and loud acclaim and wild cheers of the Afsharid troops present. This was the signal to start the onslaught and carnage. Almost immediately, the fully-armed Afsharid Army of occupation turned their swords and guns on to the unarmed and defenceless civilians in the city. The Afsharid soldiers were given full licence to do as they pleased and promised a share of the wealth as the city was plundered.

Areas of Delhi such as Chandni Chowk, Dariba Kalan, Fatehpuri, Faiz Bazar, Hauz Kazi, Johri Bazar and the Lahori, Ajmeri and Kabuli gates, all of which were densely populated by both Hindus and Muslims, were soon covered with corpses. Muslims, like Hindus, resorted to killing their women, children and themselves rather than submit to the Afsharid soldiers.

In the words of the Tazkira:

Here and there some opposition was offered, but in most places people were butchered unresistingly. The Persians laid violent hands on everything and everybody. For a long time, streets remained strewn with corpses, as the walks of a garden with dead leaves and flowers. The town was reduced to ashes.[14]

Muhammad Shah was forced to beg for mercy.[15] These horrific events were recorded in contemporary chronicles such as the Tarikh-e-Hindi of Rustam Ali, the Bayan-e-Waqai of Abdul Karim and the Tazkira of Anand Ram Mukhlis.[14]

Finally, after many hours of desperate pleading by the Mughals for mercy, Nader Shah relented and signalled a halt to the bloodshed by sheathing his battle sword once again.

Casualties

editIt has been estimated that during the course of six hours in one day, 22 March 1739, approximately 20,000 to 30,000 Indian men, women and children were slaughtered by the Afsharid troops during the massacre in the city.[16] Exact casualty figures are uncertain, as after the massacre, the bodies of the victims were simply buried in mass burial pits or cremated in grand funeral pyres without any proper record being made of the numbers cremated or buried. In addition, some 10,000 women and children were taken slaves, according to a representative of the Dutch East India Company in Delhi.[13]

Plunder

editThe city was sacked for several days. An enormous fine of 20 million rupees was levied on the people of Delhi. Muhammad Shah handed over the keys to the Imperial Treasury, and lost the Peacock Throne, to Nader Shah, which thereafter served as a symbol of Persian imperial might. Amongst a treasure trove of other fabulous jewels, Nader also gained the Koh-i-Noor and Darya-i-Noor ("Mountain of Light" and "Sea of Light", respectively) diamonds; they are now part of the British and Iranian National Jewels, respectively. Nader and his Afsharid troops left Delhi on 16 May 1739, but before they left, he ceded back all territories to the east of the Indus, which he had overrun, to Muhammad Shah.[17] The sack of the city and defeat of the Mughals was made easier since both parties were originally from Persian cultures.[18][page needed]

Aftermath

editOn Nader's return to Iran, Sikhs fell upon his army and seized a large amount of booty and freed the slaves in captivity and Nader's army could not pursue them successfully as they were oppressed by the scorching heat of May, and being overloaded with booty.[19][20][21][18][page needed] But, still the yield of plunder seized from Delhi was so great that Nader stopped taxation in Persia for a period of three years following his return.[4][22] The Governor of Sindh did not comply with Nader Shah's demands. Nader Shah's victory against the crumbling Mughal Empire in the East meant that he could afford to turn to the West and face the Ottomans. The Ottoman Sultan Mahmud I initiated the Ottoman–Persian War (1743–1746), in which Muhammad Shah closely cooperated with the Ottomans until his death in 1748.[23] According to Axworthy, Nader's Indian campaign alerted the East India Company to the extreme weakness of the Mughal Empire and the possibility of expanding to fill the power vacuum. Axworthy claims that without Nader, "eventual British rule in India would have come later and in a different form, perhaps never at all – with important global effects".[24]

Nader's son, Nasrollah, married a Mughal princess after the sack.[18][page needed]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Despite the defeat at Karnal and the triumphal entry of the Persians, the inhabitants of Delhi were not overawed by their conquerors at first."[1]

- ^ "Another significant incident marked the reception. The intrigues of Sa’adat Khan, the governor of Awadh (Oudh), and the Emperor’s other senior nobles, including the Nezam ol-Molk (the regent or viceroy of the Deccan) had done much to weaken the Moghul State prior to the Persian invasion. Sa’adat Khan’s rashness had led directly to the disastrous Moghul defeat at the battle of Karnal on 24 February, and his own capture."[2]

- ^ "Nader may well have intended, despite his reinstatement of Mohammad Shah before his departure from Delhi, that he or one of his sons would return to India at a later stage and establish permanent Persian rule there. His annexation of the former Moghul territories west of the Indus, confirmed before he left Delhi, would have facilitated this, as would his naval expansion in the Persian Gulf."[2]

References

edit- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 4.

- ^ a b Axworthy 2006, p. 3.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze, Alexander, ed. (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 271–272.

- ^ a b "Nadir Shah". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 March 2024.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 187.

- ^ Tucker 2006, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Tucker 2006, p. 60.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b c d "Nadir Shah in India : Sarkar, Jadunath : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming". Internet Archive. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "An Outline of the History of Persia During the Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722–1922)". Edward G. Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 33. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ a b William Dalrymple, Anita Anand (2017). Koh-i-Noor. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1408888858.

- ^ a b "When the dead speak". Hindustan Times. 7 March 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Marshman, P. 200

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 212, 216.

- ^ a b c Axworthy 2006.

- ^ Hari Ram Gupta (1999). History of the Sikhs: Evolution of Sikh confederacies, 1708–1769. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 54. ISBN 9788121502481.

- ^ Vidya Dhar Mahajan (2020). Modern Indian History. S. Chand Limited. p. 57. ISBN 9789352836192.

- ^ Paul Joseph (2016). The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781483359908.

- ^ This section: Axworthy 2006, pp. 1–16, 175–210

- ^ Naimur Rahman Farooqi (1989). Mughal-Ottoman relations: a study of political & diplomatic relations between Mughal India and the Ottoman Empire, 1556–1748. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. xvi.

Sources

edit- Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1850437062.

- Babaie, Sussan (2018). "Nader Shah, the Delhi Loot, and the 18th-Century Exotics of Empire". In Axworthy, Michael (ed.). Crisis, Collapse, Militarism and Civil War: The History and Historiography of 18th Century Iran. Oxford University Press. pp. 215–234. ISBN 978-0190250331.

- John Clark Marshman (1863). "Nadir Shah". The History of India. Serampore Press. p. 199.

- Tucker, Ernest S. (2006). Nadir Shah's Quest for Legitimacy in Post-Safavid Iran. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813029641.

Further reading

edit- "Muhammad Shah". The Cambridge History of India. CUP Archive. 358–364.

- Jassa Singh Ahluwalia:The Forgotten Hero of Punjab by Harish Dhillon

- Grant, RG: Battle

- (Nader Shah) Until His Assassination In A.D. 1747. A Literary History of Persia by Edward G. Browne. Publisher T. Fisher Unwin, 1924.