The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisfaction of the Greek cities of Asia Minor with the tyrants appointed by Persia to rule them, along with the individual actions of two Milesian tyrants, Histiaeus and Aristagoras. The cities of Ionia had been conquered by Persia around 540 BC, and thereafter were ruled by native tyrants, nominated by the Persian satrap in Sardis. In 499 BC, the tyrant of Miletus, Aristagoras, launched a joint expedition with the Persian satrap Artaphernes to conquer Naxos, in an attempt to bolster his position. The mission was a debacle, and sensing his imminent removal as tyrant, Aristagoras chose to incite the whole of Ionia into rebellion against the Persian king Darius the Great.

| Ionian Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||

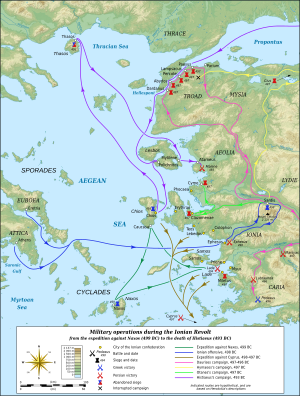

Location and main events of the Ionian Revolt. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Achaemenid Empire | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

In 498 BC, supported by troops from Athens and Eretria, the Ionians marched on, captured, and burnt Sardis. However, on their return journey to Ionia, they were followed by Persian troops, and decisively beaten at the Battle of Ephesus. This campaign was the only offensive action by the Ionians, who subsequently went on the defensive. The Persians responded in 497 BC with a three pronged attack aimed at recapturing the outlying areas of the rebellion, but the spread of the revolt to Caria meant that the largest army, under Daurises, relocated there. While initially campaigning successfully in Caria, this army was annihilated in an ambush at the Battle of Pedasus. This battle had started a stalemate for the rest of 496 BC and 495 BC.

By 494 BC the Persian army and navy had regrouped, and they made straight for the epicentre of the rebellion at Miletus. The Ionian fleet sought to defend Miletus by sea, but was decisively beaten at the Battle of Lade, after the defection of the Samians. Miletus was then besieged, captured, and its population was brought under Persian rule. This double defeat effectively ended the revolt, and the Carians surrendered to the Persians as a result. The Persians spent 493 BC reducing the cities along the west coast that still held out against them, before finally imposing a peace settlement on Ionia which was generally considered to be both just and fair.

The Ionian Revolt constituted the first major conflict between Greece and the Persian Empire, and as such represents the first phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. Although Asia Minor had been brought back into the Persian fold, Darius vowed to punish Athens and Eretria for their support of the revolt. Moreover, seeing that the myriad city states of Greece posed a continued threat to the stability of his Empire, according to Herodotus, Darius decided to conquer the whole of Greece. In 492 BC, the first Persian invasion of Greece, the next phase of the Greco-Persian Wars, began as a direct consequence of the Ionian Revolt.

Sources

editPractically the only primary source for the Ionian Revolt is the Greek historian Herodotus.[2] Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History',[3] was born in 484 BC in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his 'Enquiries' (Greek—Historia; English—(The) Histories) around 440–430 BC, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 450 BC).[4] Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least from the point of view of Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it.[4] As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."[4]

Some subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, criticised Herodotus, starting with Thucydides.[5][6] Nevertheless, Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the siege of Sestos), and therefore presumably felt that Herodotus's history was accurate enough not to need re-writing or correcting.[6] Plutarch criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as philobarbaros (φιλοβάρβαρος, "barbarian-lover") and for not being pro-Greek enough, which suggests that Herodotus might actually have done a reasonable job of being even-handed.[7] A negative view of Herodotus was passed on to Renaissance Europe, though he remained widely read.[8] However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by the age of democracy and some archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events.[9] The prevailing modern view is that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism.[9] Nevertheless, there are still many historians who believe Herodotus' account has an anti-Persian bias and that much of his story was embellished for dramatic effect.[10]

Background

editIn the 12th century BC, the Mycenaean civilization fell as part of the Late Bronze Age collapse. During the subsequent dark age, significant numbers of Greeks emigrated to Asia Minor and settled there. These settlers were from three tribal groups: the Aeolians, Dorians and Ionians.[11] The Ionians had settled along the coasts of Lydia and Caria, founding the twelve cities which made up Ionia.[11] These cities (part of the Ionian League) were Miletus, Myus and Priene in Caria; Ephesus, Colophon, Lebedos, Teos, Clazomenae, Phocaea and Erythrae in Lydia; and the islands of Samos and Chios.[12] Although the Ionian cities were independent from each other, they acknowledged their shared heritage, and had a common temple and meeting place, the Panionion. They thus formed a 'cultural league', to which they would admit no other cities, or even other tribal Ionians.[13][14] The cities of Ionia had remained independent until they were conquered by the famous Lydian king Croesus, in around 560 BC.[15] The Ionian cities then remained under Lydian rule until Lydia was in turn conquered by the nascent Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus the Great.[16]

While fighting the Lydians, Cyrus had sent messages to the Ionians asking them to revolt against Lydian rule, which the Ionians had refused to do.[16] After Cyrus completed the conquest of Lydia, the Ionian cities now offered to be his subjects under the same terms as they had been subjects of Croesus.[16] Cyrus refused, citing the Ionians' unwillingness to help him previously. The Ionians thus prepared to defend themselves, and Cyrus sent the Median general Harpagus to conquer Ionia.[17] He first attacked Phocaea; the Phocaeans decided to entirely abandon their city and sail into exile in Sicily, rather than become Persian subjects (although many subsequently returned).[18] Some Teians also chose to emigrate when Harpagus attacked Teos, but the rest of the Ionians remained, and were in turn conquered.[19]

The Persians found the Ionians difficult to rule. Elsewhere in the empire, Cyrus was able to identify elite native groups to help him rule his new subjects – such as the priesthood of Judea.[20] No such group existed in Greek cities at this time; while there was usually an aristocracy, this was inevitably divided into feuding factions.[20] The Persians thus settled for sponsoring a tyrant in each Ionian city, even though this drew them into the Ionians' internal conflicts. Furthermore, a tyrant might develop an independent streak, and have to be replaced.[20] The tyrants themselves faced a difficult task; they had to deflect the worst of their fellow citizens' hatred, while staying in the favour of the Persians.[20]

About 40 years after the Persian conquest of Ionia, and in the reign of the fourth Persian king, Darius the Great, the stand-in Milesian tyrant Aristagoras found himself in this familiar predicament.[21] Aristagoras's uncle Histiaeus had accompanied Darius on campaign in 513 BC, and when offered a reward, had asked for part of the conquered Thracian territory. Although this was granted, Histiaeus's ambition alarmed Darius's advisors, and Histiaeus was thus further 'rewarded' by being compelled to remain in Susa as Darius's "Royal Table-Companion".[21] Taking over from Histiaeus, Aristagoras was faced with bubbling discontent in Miletus. In 500 BC, Aristagoras was approached by some exiles from Naxos, who asked him to take control of the island.[22] Seeing an opportunity to strengthen his position in Miletus by conquering Naxos, Aristagoras approached the satrap of Lydia, Artaphernes, with a proposal. If Artaphernes provided an army, Aristagoras would conquer the island, thus extending the boundaries of the empire for Darius, and he would then give Artaphernes a share of the spoils to cover the cost of raising the army.[23] Artaphernes agreed in principle, and asked Darius for permission to launch the expedition. Darius assented to this, and a force of 200 triremes was assembled in order to attack Naxos the following year.[24]

Naxos campaign (499 BC)

editIn the spring of 499 BC, Artaphernes readied the Persian force, and placed his cousin Megabates in command.[24] He then sent ships on to Miletus, where the Ionian troops levied by Aristagoras embarked, and the force then set sail for Naxos.[25]

The expedition quickly descended into a debacle. Aristagoras fell out with Megabates on the journey towards Naxos, and Herodotus says that Megabates then sent messengers to Naxos, warning the Naxians of the force's intention.[25] It is also possible, however, that this story was spread by Aristagoras after the event, by way of a justification for the subsequent failure of the campaign.[2] At any rate, the Naxians were able to prepare properly for a siege, and the Persians arrived to a well-defended city.[26] The Persians laid siege to the Naxians for four months, but eventually they and Aristagoras both ran out of money. The force sailed back to the mainland without a victory.[26]

Start of the Ionian Revolt (499 BC)

editWith the failure of his attempt to conquer Naxos, Aristagoras found himself in dire straits; he was unable to repay Artaphernes, and had, moreover, alienated himself from the Persian royal family. He fully expected to be stripped of his position by Artaphernes. In a desperate attempt to save himself, Aristagoras chose to incite his own subjects, the Milesians, to revolt against their Persian masters, thereby beginning the Ionian Revolt.[27]

In autumn 499 BC, Aristagoras held a meeting with the members of his faction in Miletus. He declared that in his opinion the Milesians should revolt, to which all but the historian Hecataeus agreed.[28] At the same time, a messenger sent by Histiaeus arrived in Miletus, imploring Aristagoras to rebel against Darius. Herodotus suggests that this was because Histiaeus was desperate to return to Ionia, and thought he would be sent to Ionia if there was a rebellion.[27] Aristagoras therefore openly declared his revolt against Darius, abdicated from his role as tyrant, and declared Miletus to be a democracy.[29] Herodotus has no doubt that this was only a pretence on Aristagoras's part of giving up power. Rather it was designed to make the Milesians enthusiastically join the rebellion.[30] The army that had been sent to Naxos was still assembled at Myus[28] and included contingents from other Greek cities of Asia Minor (i.e. Aeolia and Doris) as well as men from Mytilene, Mylasa, Termera and Cyme.[30] Aristagoras sent men to capture all the Greek tyrants present in the army and handed them over to their respective cities in order to gain the cooperation of those cities.[30] Bury and Meiggs stated that the handovers were done without bloodshed with the exception of Mytilene, whose tyrant was stoned to death; tyrants elsewhere were simply banished.[31][32] It has also been suggested (Herodotus does not explicitly say so) that Aristagoras incited the whole army to join his revolt,[2] and also took possession of the ships that the Persians had supplied.[29] If the latter is true, it may explain the length of time it took for the Persians to launch a naval assault on Ionia, since they would have needed to build a new fleet.[33]

Although Herodotus presents the revolt as a consequence of Aristagoras and Histiaeus's personal motives, it is clear that Ionia must have been ripe for rebellion anyway. The primary grievance was the tyrants installed by the Persians.[2] While Greek states had in the past often been ruled by tyrants, this was a form of government on the decline. Moreover, past tyrants had tended (and needed) to be strong and able leaders, whereas the rulers appointed by the Persians were simply the representatives of the Persians. Backed by Persian military might, these tyrants did not need the support of the population, and could thus rule absolutely.[2] Aristagoras's actions have thus been likened to tossing a flame into a kindling box; they incited rebellion across Ionia, and tyrannies were everywhere abolished, and democracies established in their place.[29]

Aristagoras had brought all of Hellenic Asia Minor into revolt, but evidently realised that the Greeks would need other allies in order to successfully fight the Persians.[32][34] In the winter of 499 BC, he first sailed to Sparta, the pre-eminent Greek state in matters of war. However, despite Aristagoras's entreaties, the Spartan king Cleomenes I turned down the offer to lead the Greeks against the Persians. Aristagoras therefore turned instead to Athens.[34]

Athens had recently become a democracy, overthrowing its own tyrant Hippias. In their fight to establish the democracy, the Athenians had asked the Persians for aid (which was not in the end needed), in return for submitting to Persian overlordship.[35] Some years later, Hippias had attempted to regain power in Athens, assisted by the Spartans. This attempt failed and Hippias fled to Artaphernes, and tried to persuade him to subjugate Athens.[36] The Athenians dispatched ambassadors to Artaphernes to dissuade him from taking action, but Artaphernes merely instructed the Athenians to take Hippias back as tyrant.[34] Needless to say, the Athenians had balked at this, and resolved instead to be openly at war with Persia.[36] Since they were already an enemy of Persia, Athens was already in a position to support the Ionian cities in their revolt.[34] The fact that the Ionian democracies were inspired by the example of the Athenian democracy no doubt helped persuade the Athenians to support the Ionian Revolt, especially since the cities of Ionia were (supposedly) originally Athenian colonies.[34]

Aristagoras was also successful in persuading the city of Eretria to send assistance to the Ionians for reasons that are not completely clear. Possibly commercial reasons were a factor; Eretria was a mercantile city, whose trade was threatened by Persian dominance of the Aegean.[34] Herodotus suggests that the Eretrians supported the revolt in order to repay the support the Milesians had given Eretria some time previously, possibly referring to the Lelantine War.[37] The Athenians sent twenty triremes to Miletus, reinforced by five from Eretria. Herodotus described the arrival of these ships as the beginning of troubles between Greeks and barbarians.[31]

Ionian offensive (498 BC)

editOver the winter, Aristagoras continued to foment rebellion. In one incident, he told a group of Paeonians (originally from Thrace), who Darius had brought to live in Phrygia, to return to their homeland. Herodotus says that his only purpose in doing this was to vex the Persian high command.[38]

Sardis

editIn the spring of 498 BC, an Athenian force of twenty triremes, accompanied by five from Eretria, set sail for Ionia.[33] They joined up with the main Ionian force near Ephesus.[40] Declining to personally lead the force, Aristagoras appointed his brother Charopinus and another Milesian, Hermophantus, as generals.[37]

This force was then guided by the Ephesians through the mountains to Sardis, Artaphernes's satrapal capital.[33] The Greeks caught the Persians unaware, and were able to capture the lower city. However, Artaphernes still held the citadel with a significant force of men.[40] The lower city then caught on fire, Herodotus suggests accidentally, which quickly spread. The Persians in the citadel, being surrounded by a burning city, emerged into the market-place of Sardis, where they fought with the Greeks, forcing them back. The Greeks, demoralised, then retreated from the city, and began to make their way back to Ephesus.[41]

Herodotus reports that when Darius heard of the burning of Sardis, he swore vengeance upon the Athenians (after asking who they indeed were), and tasked a servant with reminding him three times each day of his vow: "Master, remember the Athenians".[42]

Battle of Ephesus

editHerodotus says that when the Persians in Asia Minor heard of the attack on Sardis, they gathered together, and marched to the relief of Artaphernes.[43] When they arrived at Sardis, they found the Greeks recently departed. So they followed their tracks back towards Ephesus.[43] They caught up with the Greeks outside Ephesus and the Greeks were forced to turn and prepare to fight.[43] Holland suggests that the Persians were primarily cavalry (hence their ability to catch up with the Greeks).[33] The typical Persian cavalry of the time were probably missile cavalry, whose tactics were to wear down a static enemy with volley after volley of arrows.[44]

It is clear that the demoralised and tired Greeks were no match for the Persians, and were completely routed in the battle which ensued at Ephesus.[33][43] Many were killed, including the Eretrian general, Eualcides.[43] The Ionians who escaped the battle made for their own cities, while the remaining Athenians and Eretrians managed to return to their ships and sailed back to Greece.[33][43]

Spread of the revolt

editThe Athenians now ended their alliance with the Ionians, since the Persians had proved to be anything but the easy prey that Aristagoras had described.[45] However, the Ionians remained committed to their rebellion and the Persians did not seem to follow up their victory at Ephesus.[45] Presumably these ad hoc forces were not equipped to lay siege to any of the cities. Despite the defeat at Ephesus, the revolt actually spread further. The Ionians sent men to the Hellespont and Propontis and captured Byzantium and the other nearby cities.[45] They also persuaded the Carians to join the rebellion.[45] Furthermore, seeing the spread of the rebellion, the kingdoms of Cyprus also revolted against Persian rule without any outside persuasion.[46]

Persian counter-offensive (497–495 BC)

editHerodotus's narrative after the Battle of Ephesus is ambiguous in its exact chronology; historians generally place Sardis and Ephesus in 498 BC.[33][47] Herodotus next describes the spread of the revolt (thus also in 498 BC), and says that the Cypriots had one year of freedom, therefore placing the action in Cyprus to 497 BC.[48] He next says that

Daurises, Hymaees, and Otanes, all of them Persian generals and married to daughters of Darius, pursued those Ionians who had marched to Sardis, and drove them to their ships. After this victory they divided the cities among themselves and sacked them.[48]

This passage implies these Persian generals counter-attacked immediately after the Battle of Ephesus. However, the cities that Herodotus describes Daurises as besieging were on the Hellespont,[49] which (by Herodotus's own reckoning) did not become involved in the revolt until after Ephesus. It is therefore easiest to reconcile the account by assuming that Daurises, Hymaees, and Otanes waited until the next campaigning season (i.e., 497 BC), before going on the counter-offensive. The Persian actions that Herodotus described at the Hellespont and in Caria seem to be in the same year, and most commentators place them in 497 BC.[47]

Cyprus

editIn Cyprus, all the kingdoms had revolted except that of Amathus. The leader of the Cypriot revolt was Onesilus, brother of the king of Salamis, Gorgus. Gorgus did not want to revolt, so Onesilus locked his brother out of the city and made himself king. Gorgus went over to the Persians, and Onesilus persuaded the other Cypriots, apart from the Amathusians, to revolt. He then settled down to besiege Amathus.[46]

The following year (497 BC), Onesilus (still besieging Amathus), heard that a Persian force under Artybius had been dispatched to Cyprus. Onesilus thus sent messengers to Ionia, asking them to send reinforcements, which they did, "in great force".[50] A Persian army eventually arrived in Cyprus, supported by a Phoenician fleet. The Ionians opted to fight at sea and defeated the Phoenicians.[51] In the simultaneous land battle outside Salamis, the Cypriots gained an initial advantage, killing Artybius. However, the defection of two contingents to the Persians crippled their cause, they were routed and Onesilus and Aristocyprus, king of Soli, were both killed. The revolt in Cyprus was thus crushed and the Ionians sailed home.[52]

Hellespont and Propontis

editThe Persian forces in Asia Minor seem to have been reorganised in 497 BC, with three of Darius's sons-in-law, Daurises, Hymaees, and Otanes, taking charge of three armies.[47] Herodotus suggests that these generals divided up the rebellious lands between themselves and then set out to attack their respective areas.[48]

Daurises, who seems to have had the largest army, initially took his army to the Hellespont.[47] There, he systematically besieged and took the cities of Dardanus, Abydos, Percote, Lampsacus, and Paesus, each in a single day according to Herodotus.[49] However, when he heard that the Carians were revolting, he moved his army southwards to attempt to crush this new rebellion.[49] This places the timing of the Carian revolt to early 497 BC.[47]

Hymaees went to the Propontis and took the city of Cius. After Daurises moved his forces towards Caria, Hymaees marched towards the Hellespont and captured many of the Aeolian cities as well as some of the cities in the Troad. However, he then fell ill and died, ending his campaign.[53] Meanwhile, Otanes, together with Artaphernes, campaigned in Ionia (see below).[54]

Caria (496 BC)

editBattle of the Marsyas

editHearing that the Carians had rebelled, Daurises led his army south into Caria. The Carians gathered at the "White Pillars", on the Marsyas River (the modern Çine), a tributary of the Meander.[55] Pixodorus, a relative of the king of Cilicia, suggested that the Carians should cross the river and fight with it at their backs, so as to prevent retreat and thus make them fight more bravely. This idea was rejected and the Carians made the Persians cross the river to fight them.[55] The ensuing battle was, according to Herodotus, a long affair, with the Carians fighting obstinately before eventually succumbing to the weight of Persian numbers. Herodotus suggests that 10,000 Carians and 2,000 Persians died in the battle.[56]

Battle of Labraunda

editThe survivors of Marsyas fell back to a sacred grove of Zeus at Labraunda and deliberated whether to surrender to the Persians or to flee Asia altogether.[56] However, while deliberating, they were joined by a Milesian army, and with these reinforcements resolved instead to carry on fighting. The Persians then attacked the army at Labraunda, and inflicted an even heavier defeat, with the Milesians suffering particularly bad casualties.[57]

Battle of Pedasus

editAfter the double victory over the Carians, Daurises began the task of reducing the Carian strongholds. The Carians resolved to fight on, and decided to lay an ambush for Daurises on the road through Pedasus.[58] Herodotus implies that this occurred more or less directly after Labraunda, but it has also been suggested that Pedasus occurred the following year (496 BC), giving the Carians time to regroup.[47] The Persians arrived at Pedasus during the night, and the ambush was sprung to great effect. The Persian army was annihilated and Daurises and the other Persian commanders were slain.[58] The disaster at Pedasus seems to have created a stalemate in the land campaign, and there was apparently little further campaigning in 496 BC and 495 BC.[47]

Ionia

editThe third Persian army, under the command of Otanes and Artaphernes, attacked Ionia and Aeolia.[59] They re-took Clazomenae and Cyme, probably in 497 BC, but then seem to have been less active in 496 BC and 495 BC, probably as a result of the calamity in Caria.[47]

At the height of the Persian counter-offensive, Aristagoras, sensing his untenable position, decided to abandon his responsibilities as leader of Miletus and of the revolt. He left Miletus with all the members of his faction who would accompany him, and went to the part of Thrace that Darius had granted to Histiaeus after the campaign of 513 BC.[60] Herodotus, who evidently has a rather negative view of him, suggests that Aristagoras simply lost his nerve and fled. Some modern historians have suggested that he went to Thrace to exploit the greater natural resources of the region, and thus support the revolt.[2] Others have suggested that finding himself at the centre of an internal conflict in Miletus, he chose to go into exile rather than exacerbate the situation.[47]

In Thrace, he took control of the city that Histiaeus had founded, Myrcinus (site of the later Amphipolis), and started campaigning against the local Thracian population.[60] However, during one campaign, probably in either 497 BC or 496 BC, he was killed by the Thracians.[61] Aristagoras was the one man who might have been able to provide the revolt with a sense of purpose, but after his death the revolt was left effectively leaderless.[33][47]

Shortly after this, Histiaeus was released from his duties in Susa by Darius and sent to Ionia. He had persuaded Darius to let him travel to Ionia by promising to make the Ionians end their revolt. However, Herodotus leaves us in no doubt that his real aim was simply to escape his quasi-captivity in Persia.[62] When he arrived in Sardis, Artaphernes directly accused him of fomenting the rebellion with Aristagoras: "I will tell you, Histiaeus, the truth of this business: it was you who stitched this shoe, and Aristagoras who put it on."[63] Histiaeus fled that night to Chios and eventually made his way back to Miletus.[64] However, having just got rid of one tyrant, the Milesians were in no mood to receive Histiaeus back. He therefore went to Mytilene in Lesbos and persuaded the Lesbians to give him eight triremes. He set sail for Byzantium with all those who would follow him. There he established himself, seizing all ships that attempted to sail through the Bosporus, unless they agreed to serve him.[64]

End of the revolt (494–493 BC)

editBattle of Lade

editBy the sixth year of the revolt (494 BC), the Persian forces had regrouped. The available land forces were gathered into one army, and were accompanied by a fleet supplied by the re-subjugated Cypriots, along with Egyptians, Cilicians and Phoenicians. The Persians headed directly to Miletus, paying little attention to other strongholds, presumably intending to tackle the revolt at its epicentre.[65] The Median general Datis, an expert on Greek affairs, was certainly dispatched to Ionia by Darius at this time. It is therefore possible that he was in overall command of this Persian offensive.[2]

Hearing of the approach of this force, the Ionians met at the Panionium, and decided not to attempt to fight on land, leaving the Milesians to defend their walls. Instead, they opted to gather every ship they could and make for the island of Lade, off the coast of Miletus, in order to "fight for Miletus at sea".[65] The Ionians were joined by the Aeolian islanders from Lesbos, and altogether they had 353 triremes.[66]

According to Herodotus, the Persian commanders were concerned that they would not be able to defeat the Ionian fleet and, therefore, would not be able to take Miletus. So they sent the exiled Ionian tyrants to Lade, where each tried to persuade his fellow citizens to desert to the Persians.[67] This approach was initially unsuccessful,[68] but in the week-long delay before the battle, divisions arose in the Ionian camp.[69] These divisions led to the Samians secretly agreeing to the terms offered by the Persians, but remained with the other Ionians for the time being.[70]

Soon after, the Persian fleet moved to attack the Ionians, who sailed out to meet them. However, as the two sides neared each other, the Samians sailed away back to Samos, as they had agreed with the Persians. The Lesbians, seeing their neighbours in the battle-line sail away, promptly fled as well, causing the rest of the Ionian line to dissolve.[71] The Chians, together with a small number of ships from other cities, stubbornly remained and fought the Persians, but most of the Ionians fled to their cities.[72] The Chians fought valiantly, at one point breaking the Persian line and capturing many ships, but sustaining many losses of their own; eventually the remaining Chian ships sailed away, thereby ending the battle.[73]

Fall of Miletus

editWith the defeat of the Ionian fleet, the revolt was effectively over. Miletus was closely invested, the Persians "mining the walls and using every device against it, until they utterly captured it". According to Herodotus, most of the men were killed, and the women and children were enslaved.[74] Archaeological evidence partially substantiates this, showing widespread signs of destruction, and abandonment of much of the city in the aftermath of Lade.[47] However, some Milesians did remain in (or quickly returned to) Miletus, though the city would never recapture its former greatness.[2]

Miletus was thus notionally "left empty of Milesians";[75] the Persians took the city and coastal land for themselves, and gave the rest of the Milesian territory to Carians from Pedasus.[76] The captive Milesians were brought before Darius in Susa, who settled them at "Ampé"[77] on the coast of the Persian Gulf, near the mouth of the Tigris.

Many Samians were appalled by the actions of their generals at Lade, and resolved to emigrate before their old tyrant, Aeaces of Samos, returned to rule them. They accepted an invitation from the people of Zancle to settle on the coast of Sicily, and took with them the Milesians who had managed to escape from the Persians.[75] Samos itself was spared from destruction by the Persians because of the Samian defection at Lade.[78] Most of Caria now surrendered to the Persians, although some strongholds had to be captured through force.[78]

Histiaeus's campaign (493 BC)

editChios

editWhen Histiaeus heard of the fall of Miletus, he seems to have appointed himself as leader of the resistance against Persia.[47] Setting out from Byzantium with his force of Lesbians, he sailed to Chios. The Chians refused to receive him, so he attacked and destroyed the remnants of the Chian fleet. Crippled by the two defeats at sea, the Chians then acquiesced to Histiaeus's leadership.[79]

Battle of Malene

editHistiaeus now gathered a large force of Ionians and Aeolians and went to besiege Thasos. However, he then received the news that the Persian fleet was setting out from Miletus to attack the rest of Ionia, so he quickly returned to Lesbos.[80] In order to feed his army, he led foraging expeditions to the mainland near Atarneus and Myus. A large Persian force under Harpagus was in the area and eventually intercepted one foraging expedition near Malene. The ensuing battle was hard fought, but was ended by a successful Persian cavalry charge, routing the Greek line.[81] Histiaeus himself surrendered to the Persians, thinking that he would be able to talk himself into a pardon from Darius. However, he was taken to Artaphernes instead, who, fully aware of Histiaeus's past treachery, impaled him and then sent his embalmed head to Darius.[82]

Final operations (493 BC)

editThe Persian fleet and army wintered at Miletus, before setting out in 493 BC to finally stamp out the last embers of the revolt. They attacked and captured the islands of Chios, Lesbos, and Tenedos. On each, they made a 'human-net' of troops and swept across the whole island to flush out any hiding rebels.[83] They then moved over to the mainland and captured each of the remaining cities of Ionia, similarly seeking out any remaining rebels.[83] Although the cities of Ionia were undoubtedly harrowed in the aftermath, none seems to have suffered quite the fate of Miletus. Herodotus says that the Persians chose the most handsome boys from each city and castrated them, and chose the most beautiful girls and sent them away to the king's harem, and then burnt the temples of the cities.[84] While this is possibly true, Herodotus also probably exaggerates the scale of devastation.[2] In a few years, the cities had more-or-less returned to normal and they were able to equip a large fleet for the second Persian invasion of Greece, just 13 years later.[2][85]

The Persian army then re-conquered the settlements on the Asian side of the Propontis, while the Persian fleet sailed up the European coast of the Hellespont, taking each settlement in turn. With all of Asia Minor now firmly returned to Persian rule, the revolt was finally over.[86]

Aftermath

editOnce the inevitable punishment of the rebels had occurred, the Persians were in the mood for conciliation. Since these regions were now Persian territory again, it made no sense to harm their economies further or to drive the people to further rebellions. Artaphernes thus set out to re-establish a workable relationship with his subjects.[88] He summoned representatives from each Ionian city to Sardis, and told them that henceforth, rather than continually quarrelling and fighting between themselves, disputes would be resolved by arbitration, seemingly by a panel of judges.[47] Furthermore, he re-surveyed the land of each city, and set their tribute level in proportion to its size.[89] Artaphernes had also witnessed just how much the Ionians disliked tyrannies, and began to reconsider his position on the local governance of Ionia.[88] The following year, Mardonius, another son-in-law of Darius, would travel to Ionia and abolish the tyrannies, replacing them with democracies.[90] The peace established by Artaphernes would long be remembered as just and fair.[88] Darius actively encouraged the Persian nobility of the area to participate in Greek religious practices, especially those dealing with Apollo.[91] Records from the period indicate that the Persian and Greek nobility began to intermarry, and the children of Persian nobles were given Greek names instead of Persian names. Darius' conciliatory policies were used as a type of propaganda campaign against the mainland Greeks, so that in 491 BC, when Darius sent heralds throughout Greece demanding submission (earth and water), initially most city-states accepted the offer, Athens and Sparta being the most prominent exceptions.[92]

For the Persians, the only unfinished business that remained by the end of 493 BC was to exact punishment on Athens and Eretria for supporting the revolt.[88] The Ionian Revolt had severely threatened the stability of Darius's empire, and the states of mainland Greece would continue to threaten that stability unless dealt with. Darius thus began to contemplate the complete conquest of Greece, beginning with the destruction of Athens and Eretria.[88]

Therefore, the first Persian invasion of Greece effectively began in the following year, 492 BC, when Mardonius was dispatched (via Ionia) to complete the pacification of the land approaches to Greece and push on to Athens and Eretria if possible.[90] Thrace was re-subjugated, having broken loose from Persian rule during the revolts and Macedon compelled to become a vassal of Persia. However, progress was halted by a naval disaster.[90] A second expedition was launched in 490 BC under Datis and Artaphernes, son of the satrap Artaphernes. This amphibious force sailed across the Aegean, subjugating the Cyclades, before arriving off Euboea. Eretria was besieged, captured and destroyed, and the force then moved onto Attica. Landing at the Bay of Marathon, they were met by an Athenian army and defeated in the famous Battle of Marathon, ending the first Persian attempt to subdue Greece.[93]

Significance

editThe Ionian Revolt was primarily of significance as the opening chapter in, and causative agent of, the Greco-Persian Wars, which included the two invasions of Greece and the famous battles of Marathon, Thermopylae and Salamis.[2] For the Ionian cities themselves, the revolt ended in failure, and substantial losses, both material and economic. However, Miletus aside, they recovered relatively quickly and prospered under Persian rule for the next forty years.[2] For the Persians, the revolt was significant in drawing them into an extended conflict with the states of Greece which would last for fifty years, over which time they would sustain considerable losses.[94]

Militarily, it is difficult to draw too many conclusions from the Ionian Revolt, save for what the Greeks and Persians may (or may not) have learnt about each other. Certainly, the Athenians, and Greeks in general, seem to have been impressed by the power of Persian cavalry, with the Greek armies displaying considerable caution during the following campaigns when confronted by the Persian cavalry.[95][96] Conversely, the Persians seem not to have realised or noticed the potential of the Greek hoplites as heavy infantry. At the Battle of Marathon, in 490 BC, the Persians took little heed of a primarily hoplitic army, resulting in their defeat. Furthermore, despite the possibility of recruiting heavy infantry from their domains, the Persians began the second invasion of Greece without doing so, and again encountered major problems in the face of Greek armies.[97] It is possible that, given the ease of their victories over the Greeks at Ephesus, and similarly armed forces at the battles of the Marsyas River and Labraunda, the Persians simply disregarded the military value of the hoplite phalanx—to their cost.[98]

Manville's theory of a power struggle between Aristagoras and Histiaeus

editHerodotus’ account is the best source available on the events that amounted to a collision between Persia, which was expanding westward, and classical Greece at its peak. Nevertheless, its depictions are often scanty and uncertain, or incomplete. One of the major uncertainties of the Ionian revolt in Herodotus is why it occurred in the first place.

In retrospect the case seems obvious: Persia disputed the Hellenes for control of cities and territories. The Hellenes had either to fight for their freedom or submit. The desirability of these material objects was certainly economic, although considerations of defence and ideology may well have played a part. These are the motives generally accepted today, after long retrospect.

Herodotus apparently knew of no such motives, or if he did, he did not care to analyse history at that level. P. B. Manville characterises his approach as the attribution of "personal motivation" to players such as Aristagoras and Histiaeus. In his view, Herodotus "may seem to overemphasise personal motivation as a cause," but he really does not. We have either to fault Herodotus for his lack of analytical perspicacity or try to find credible reasons in the historical context for actions to which Herodotus gives incomplete explanations.

Manville suggests that the unexplained places mark events in a secret scenario about which Herodotus could not have known, but he records what he does know faithfully. It is up to the historian to reconstruct the secret history by re-interpretation and speculation, a technique often used by historical novelists. Manville puts it forward as history.

The main players are portrayed by Herodotus as naturally hypocritical. They always have an ulterior motive which they go to great lengths to conceal behind persuasive lies. Thus neither Aristagoras nor Histiaeus are fighting for freedom, nor do they cooperate or collaborate. Each has a personal motive related to greed, ambition, or fear. Manville fills in the uncertainties with hypothetical motives. Thus he arrives, perhaps less credibly for his invention, at a behind-the-scenes struggle for dominance between Aristagoras and Histiaeus. They can best be described as rivals or even enemies.[99] Some of the high points of the argument are as follows.

While Histiaeus was away serving Darius, Aristagoras acted in his stead as deputy of Miletus where, it is argued, he worked on securing his own power. The word for deputy is epitropos, which he was when the Naxian deputation arrived. By the time the fleet departs for Naxos, Aristagoras has promoted himself to "tyrant of Miletus." There is no explicit statement that he asked Histiaeus' permission or was promoted by Histaeus. Instead, Aristagoras turned to Artaphernes, who was said to be jealous of Histiaeus. It is true that Artaphernes would not move without consulting the Great King, and that the latter's advisor on Greek affairs was Histiaeus. However, Manville sees a coup by Aristagoras, presuming not only that the Great King's advisor did not advise, but was kept in the dark about his own supersession.

When the expedition failed, Histiaeus sent his tattooed slave to Aristagoras, not as encouragement to revolt, but as an ultimatum. Manville provides an underlying value system to fill in the gap left by Herodotus: revolt was so unthinkable that Histiaeus could bring the fantasies of his opponent back to reality by suggesting that he do it, a sort of "go ahead, commit suicide." Histiaeus was, in Manville's speculation, ordering Aristagoras to give up his rule or suffer the consequences. Apparently, he was not being kept in the dark by the king after all. Manville leaves us to guess why the king did not just crush the revolt by returning the supposedly loyal Histiaeus to power.

However, at this time Histiaeus was still required to remain in Susa and, despite his threat, he was unable to do anything if Aristagoras did revolt. Realising that this would be his last chance to gain power Aristagoras started the revolt despite Histiaeus' threat. This is a surprise to Manville's readers, as we thought he already had power via a coup. Manville does note the contradiction mentioned above, that Aristagoras gave up tyranny, yet was able to force democracy on the other cities and command their obedience to him. We are to see in this paradox a strategy to depose Histiaeus, whom we thought was already deposed.

The tale goes on to an attempt by Histiaeus to form an alliance with Artaphernes to depose the usurper and regain his power at Miletus. Artaphernes, though he was involved in open war with Aristagoras, refuses.[100] The tale told by Manville thus contains events related by Herodotus supplemented by non-events coming from Manville's imagination.

Myres' Theory of a balance of power between thalassocracies

editJohn Myres, classical archaeologist and scholar, whose career began in the reign of Queen Victoria and did not end until 1954, close friend and companion of Arthur Evans, and intelligence officer par excellence of the British Empire, developed a theory of the Ionian Revolt that explains it in terms of the stock political views of the empire, balance of power and power vacuum. Those views, still generally familiar, assert that peace is to be found in a region controlled by competing geopolitical powers, none of which are strong enough to defeat the others. If a power drops from the roster for any reason, a "vacuum" then exists, which causes violent competition until the balance is readjusted.

In a key article of 1906, while Evans was excavating Knossos, the Ottoman Empire had lost Crete due to British intervention, and questions of the "sick man of Europe" were being considered by all the powers. Referring to the failing Ottoman Empire and the power vacuum that would be left when it fell, the young Myres published an article studying the balance of what he termed "sea-power" in the eastern Mediterranean in classical times. The word "sea-power" was intended to define his "thalassocracy."

Myres was using sea-power in a specifically British sense for the times. The Americans had their own idea of sea power, expressed in Alfred Thayer Mahan's great strategic work, "The Influence of Sea Power upon History". which advocated maintaining a powerful navy and using it for strategic purposes, such as "command of the sea," a kind of domination. The United States Naval Academy used this meaning for its motto, "ex scientia tridens", "sea-power through knowledge." It named one of its buildings, Mahan Hall.

Far different is Myres' "sea-power" and the meaning of thalassocracy, which means "rule of the seas." In contrast to "tridens," rule of the seas is not a paternalistic but democratic arrangement. Where there are rulers, there are the ruled. A kind of exclusivity is meant, such as in Rule, Britannia!. Specifically, in a thalassocracy, the fleets of the ruler may go where they will and do as they please, but the ruled may go nowhere and engage in no operation without express permission of the ruler. You need a license, so to speak, to be on ruled waters, and if you do not have it, your ships are attacked and destroyed. "Shoot on sight" is the policy. And so Carthaginian ships sank any ships in their waters, etc.

The list of thalassocracies

editThalassocracy was a new word in the theories of the late 19th century, from which some conclude it was a scholarly innovation of the times. It was rather a resurrection of a word known from a very specific classical document, which Myres calls "the List of Thalassocracies." It occurs in the Chronicon of Eusebius, the early 4th century Bishop of Caesarea Maritima, the ruins now in Israel.[101] In Eusebius, the list is a separate chronology. Jerome, 4th-century theologian and historian, creator of the Vulgate, interspersed the same items, translated into Latin, in his Chronicon of world events.[102] The items contain the words "obtinuerunt mare," strictly speaking, "obtained the sea," and not "hold sea power," although the latter meaning may be implied as a result. Just as Jerome utilised the chronology of Eusebius, so Eusebius utilised the chronology of Castor of Rhodes, a 1st-century BC historian. His work has been entirely lost except for fragments, including his list of thalassocracies. A thousand years later, the Byzantine monk, George Syncellus, also used items from the list in his massive Extract of Chronography.

Over the centuries the realisation grew that all these references to sea-power in the Aegean came from a single document, a resource now reflected in the fragments of those who relied on it. C Bunsen, whose translator was one of the first to use thalassocracy, attributed its discovery to the German scholar, Christian Gottlob Heyne[103] In a short work composed in 1769, published in 1771,[104] Eusebius’ Chronicon being known at that time only through fragments in the two authors mentioned, Heyne reconstructed the list in their Greek and Latin (with uncanny accuracy), the whole title of the article being Super Castoris epochis populorum thalattokratesanton H.E. (hoc est) qui imperium maris tenuisse dicuntur, "About Castor's epochs of thalattocratizing peoples; that is, those who are said to have held the imperium over the sea." To thalattokratize is “to rule the sea,” not just to hold sea power like any other good fellow with a strong navy. The thalattokratizer holds the imperium over the watery domain just as if it were a country, which explains how such a people can "obtain" and "have" the sea. The list presented therefore is one of successive exclusive domains. No two peoples can hold the same domain or share rule over it, although they can operate under the authority of the thalassocrat, a privilege reserved for paying allies.

According to Bunsen, the discovery and translation of the Armenian version of Eusebius' Chronicon changed the nature of the search for thalassocracy. It provided the original document, but there was a disclaimer attached, that it was in fact "an extract from the epitome of Diodorus," meaning Diodorus Siculus, a 1st-century BC historian. The disclaimer cannot be verified, as that part of Diodorus' work is missing, which, however, opens the argument to another question: if Eusebius could copy a standard source from Diodorus, why cannot Diodorus have copied it from someone else?

It is at this point that Myres picks up the argument. Noting that thalassokratesai, "be a thalassocrat," meaning "rule the waves," was used in a number of authors: elsewhere by Diodorus, by Polybius, 2nd century BC historian, of Carthage, of Chios by Strabo, 1st century BC geographer and some others, he supposes that the source document might have been available to them all (but not necessarily, the cautious Myres points out).[105] The document can be dated by its content: a list of 17 thalassocracies extending from the Lydian after the fall of Troy to the Aeginetan, which ended with the cession of power to Athens in 480 BC. The Battle of Salamis included 200 new Athenian triremes plus all the ships of its new ally, Aegina. Despite various revolts Aegina went on to become part of the Delian League, an imperial treaty of the new Athenian thalassocracy. Thucydides writes of it after 432 BC, but Herodotus, who visited Athens "as late as 444 B.C." does not know a thing about it. This tentative date for the Eusebian list does not exclude the possibility of an earlier similar document used by Herodotus.[106]

Myres' historical reconstruction of the list

editThe order of thalassocracies in the various versions of the list is nearly fixed, but the dates need considerable adjustment, which Myres sets about to reconcile through all historical sources available to him. He discovers some gaps. The solidest part of the list brackets the Ionian Revolt. The Milesian thalassocracy is dated 604-585 BC. It was ended by Alyattes of Lydia, founder of the Lydian Empire, who also fought against the Medes. The latter struggle was ended by the Eclipse of Thales at the Battle of the Halys River in 585 BC, when the combatants, interpreting the phenomenon as a sign, made peace. The Lydians were now free to turn on Miletus, which they did for the next 11 years, reducing it. When the Persians conquered Lydia in 547/546 they acquired the Ionian cities.

After 585 BC there is a gap in the list. Lesbos and one or more unknown thalassocrats held the sea in unknown order.[107] In 577 BC began the thalassocracy of Phocaea. Breaking out of its Anatolian cage, it founded Marseilles and cities in Spain and Italy, wresting a domain away from Carthage and all other opponents.[108] Their thalassocracy ended when, in the revolt of the Lydian Pactyas, who had been instructed to collect taxes by the Persians, but used them to raise an army of revolt, the Ionian cities were attacked by the Persians. The Phocaeans abandoned Phocaea about 534 BC and after much adventuring settled in the west.

The thalassocracy of Samos spans the career of the tyrant, Polycrates, there.[109] The dates of the tyrant are somewhat uncertain and variable, but at some time prior to 534 BC, he and his brothers staged a coup during a festival at Samos. Samos happened to have a large navy of pentekonters. Becoming a ship collector, he attacked and subdued all the neighbouring islands, adding their ships to his fleet. Finally he added a new model, the trireme. His reign came to an end about 517 BC when, taking up the Great King's invitation to a friendly banquet for a discussion of prospects, he was suddenly assassinated. There were no prospects.

However, if he had chosen not to attend, he was doomed anyway. Some of his trireme captains, learning of a devious plot by him to have them assassinated by Egyptian dignitaries while on official business, sailed to Sparta to beg help, which they received. The adventurous young king, Cleomenes I, was spared the trouble of killing Polycrates, but led an expedition to Samos anyway, taking the thalassocracy for two years, 517-515. Adventure and piracy not being activities approved by the Spartan people, they tagged him as insane and insisted he come home.[110] The sea was now available to Naxos, 515-505.

In modern literature

editGore Vidal describes the Ionian Revolt in his historical novel Creation, presenting events from the Persian point of view. Vidal suggests that the Ionian Revolt might have had far-reaching results not perceived by the Greeks, i.e., that King Darius had contemplated an extensive campaign of conquest in India, coveting the wealth of its kingdoms, and that this Indian campaign was aborted due to the Persians needing their military resources on the western side of their empire.

References

edit- ^ a b "a worn Chiot stater" described in Kagan p.230, Kabul hoard Coin no.12 in Daniel Schlumberger Trésors Monétaires d'Afghanistan (1953).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fine, pp 269–277.

- ^ Cicero, On the Laws I, 5.

- ^ a b c Holland, pp. xvi–xvii.

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, e.g. I, 22.

- ^ a b Finley, p. 15.

- ^ Holland, p. xxiv.

- ^ David Pipes. "Herodotus: Father of History, Father of Lies". Archived from the original on December 27, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ a b Holland, p. 377.

- ^ Fehling, pp. 1–277.

- ^ a b Herodotus I, 142–151.

- ^ Herodotus I, 142.

- ^ Herodotus I, 143.

- ^ Herodotus I, 148.

- ^ Herodotus I, 26.

- ^ a b c Herodotus I, 141.

- ^ Herodotus I, 163.

- ^ Herodotus I, 164.

- ^ Herodotus I, 169.

- ^ a b c d Holland, pp. 147–151.

- ^ a b Holland, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Herodotus V, 30.

- ^ Herodotus V, 31.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 32.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 33.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 34.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 35.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 36.

- ^ a b c Holland, pp. 155–157.

- ^ a b c Herodotus V, 37.

- ^ a b Bury & Meiggs 1975, p. 155

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 38.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Holland, pp. 160–162.

- ^ a b c d e f Holland, pp. 157–159.

- ^ Holland, p. 142.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 96.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 99.

- ^ Herodotus V, 98.

- ^ CROESUS – Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 100.

- ^ Herodotus V, 101.

- ^ Herodotus V, 105.

- ^ a b c d e f Herodotus V, 102.

- ^ Lazenby, p. 232.

- ^ a b c d Herodotus V, 103.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 104.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Boardman et al, pp. 481–490.

- ^ a b c Herodotus V, 116.

- ^ a b c Herodotus V, 117.

- ^ Herodotus V, 108.

- ^ Herodotus V, 109.

- ^ Herodotus V, 113.

- ^ Herodotus V, 122.

- ^ Herodotus V, 123.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 118.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 119.

- ^ Herodotus V, 120.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 121.

- ^ Herodotus V, 123.

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 124–126.

- ^ Thucydides IV, 102.

- ^ Herodotus V, 106–107.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 1.

- ^ a b Herodotus VI, 5.

- ^ a b Herodotus VI, 6.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 8.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 9.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 10.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 12.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 13.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 14.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 15.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 16.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 19.

- ^ a b Herodotus VI, 22.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 20.

- ^ "Deportations". Encyclopedia Iranica. Iranica Online. 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ a b Herodotus VI, 25.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 26.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 28.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 29.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 30.

- ^ a b Herodotus VI, 31.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 32.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 94.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 33.

- ^ Darius I, DNa inscription, Line 28.

- ^ a b c d e Holland, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 42.

- ^ a b c Herodotus VI, 43.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 42–45.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 49.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 94–116.

- ^ Holland, pp. 362–363.

- ^ Holland, pp. 191–193.

- ^ Lazenby, pp. 217–219.

- ^ Lazenby, pp. 23–29.

- ^ Lazenby, p. 258.

- ^ Manville 1977, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Manville 1977, pp. 82–90.

- ^ A translation can be found in "Eusebius: Chronicle". attalus.org. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ The relevant section of the Chronicon in Latin may be found at "Hieronymi Chronicon pp.16-187". tertullian.org. Retrieved 29 May 2017..

- ^ Bunsen, Christian C.J. Baron (1860). Egypt's Place in Universal History: an Historical Investigation in Five Books. Vol. 4. Translated by Cottrell, Charles H. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. p. 539.

Heyne, in his classical treatise of 1771 and 1772, submitted for the first time the Whole series to connected criticism, according to the authorities then existing, especially Syncellus and Hieronymus.

- ^ Heyne, Christian Gottlob (1771). "Commentario I: Super Castori Epochis etc". Novi Commentarii Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis.

- ^ Myres 1906, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Myres 1906, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Myres 1906, pp. 103–107.

- ^ Myres 1906, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Myres 1906, pp. 101–102

- ^ Myres 1906, pp. 99–101.

Bibliography

editAncient sources

edit- Herodotus, The Histories

- Thucydides, History of The Peloponnesian Wars

- Diodorus Siculus, Library

- Cicero, On the Laws

Modern sources

edit- Boardman J; Bury JB; Cook SA; Adcock FA; Hammond NGL; Charlesworth MP; Lewis DM; Baynes NH; Ostwald M; Seltman CT (1988). The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22804-2.

- Bury, J. B.; Meiggs, Russell (1975). A History of Greece (Fourth ed.). London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 0-333-15492-4.

- Fehling, D. (1989). Herodotus and His "Sources": Citation, Invention, and Narrative Art (Translated by J.G. Howie). Francis Cairns.

- Fine, JVA (1983). The Ancient Greeks: A Critical History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-03314-0.

- Finley, Moses (1972). "Introduction". Thucydides – History of the Peloponnesian War (translated by Rex Warner). Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044039-9.

- Holland, Tom (2006). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-51311-9.

- Lazenby, JF (1993). The Defence of Greece 490–479 BC. Aris & Phillips Ltd. ISBN 0-85668-591-7.

- Manville, P.B. (1977). "Aristagoras and Histiaios: The Leadership Struggle in the Ionian Revolt". The Classical Quarterly. 27 (1): 80–91. doi:10.1017/S0009838800024125. JSTOR 638371. S2CID 170997038.

- Myres, John L. (1906). "On the 'List of Thalassocracies' in Eusebius". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 26: 84–130. doi:10.2307/624343. JSTOR 624343. S2CID 163998082.