The Battle of Sittang Bridge was part of the Burma campaign during the Second World War. Fought on 22 and 23 February 1942, the battle was a victory for the Empire of Japan, with many losses for the British Indian Army, which was forced to retreat in disarray. Brigadier Sir John George Smyth, V.C.—who commanded the British Indian Army at Sittang Bridge—called it "the Sittang disaster".[1]

| Battle of Sittang Bridge | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Burma campaign, the South-East Asian theatre of World War II and the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

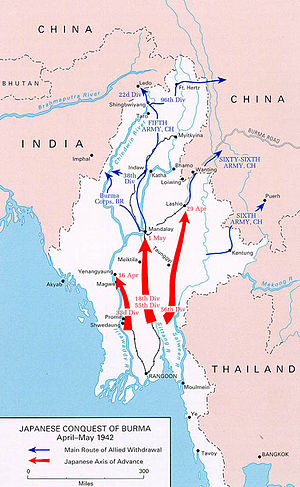

Japanese Conquest of Burma April–May 1942 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1 understrength division | 1 regiments | ||||||

The Sittang Bridge was an iron railway bridge spanning several hundred yards across the River Sittang (now Sittaung) near the south coast of Burma (now Myanmar). The 17th Indian Infantry Division had given "everything it had" at the Battle of Bilin River and was already weak.[2] Now in retreat, they finally received permission to withdraw across the Sittang on 19 February. They disengaged from the enemy under cover of night, and fell back 30 miles (50 km) westwards along the track that led to the bridge.

The Japanese 214th and 215th Regiments advanced, aiming to cut the British forces off at Sittang. Lieutenant General William Slim (later Field Marshal Sir William Slim), who took command of the Burmese theatre shortly after the battle ended, called the Sittang Bridge "the decisive battle of the first campaign".[3]

Battle

editDesperately and gallantly the two brigades still east of the river fought to break through to the great Sittang railway bridge, held by their comrades, their only hope of getting their vehicles, and indeed themselves, over the six-hundred-yard-wide stream. Then came tragedy.

—Field Marshal Sir William Slim.[4]

Retreat to the bridge

edit21 February dawned bright and hot, and the 17th Division was short of water. Japanese aircraft strafed and bombed them on the road, inflicting serious casualties and forcing them to abandon vehicles and equipment. Many men took cover in a nearby rubber plantation, the Bogyagi Rubber Estate. At 05:00, the 17th Division's headquarters came under attack at Kyaikto, but the Japanese were beaten back. A small British Indian force made up of detachments from several different units (including the Duke of Wellington's Regiment) defended the bridge.

On 22 February, the Malerkotla Sappers and Miners, led by Richard Orgill, had prepared the rail-cum-road bridge for demolition. However, the 16th Indian Infantry Brigade and 46th Indian Infantry Brigade of the 17th Division were still further to the east, cut off.[5]

Fearing paratroop landings, Smyth deployed the 1/4th Gurkhas to the western end of the bridge to hold it against attacks from the rear while the 17th Division crossed. He was obliged to send them back again when the Japanese 33 Division attacked from the east. Their first charge nearly took the east end of the bridge, and a British field hospital was captured. 3rd and 5th Gurkhas, approaching the bridge from the east, counterattacked and drove off the Japanese in "a furious battle".[6][5]

Jungle fighting at close quarters ensued, which lasted most of the day. The bridge was again nearly taken, and the attackers again beaten off. At dusk on 22 February, the British Indian Army still held the bridge.[6]

"My unpleasant and devastating news"

editSmyth had ordered his sappers to get ready to blow the bridge. At 4:30 am, in the early morning on 22 February, it became clear that it might fall within the hour. Smyth's choices were to destroy the bridge, stranding more than half of his own troops on the wrong side, or to let it stand and give the Japanese a clear march to Rangoon. According to Smyth, "Hard though it is, there is very little doubt as to what is the correct course: I give the order that the bridge shall be blown immediately." Yet only the Number 5 Span, counting from the east bank, dropped into the river, while Spans 4 and 6 were damaged but remained in place.[5]

Smyth reported this "unpleasant and devastating news"[6] to General Hutton, overall commander of the Burmese forces. Slim (1956) says: "It is easy to criticize this decision; it is not easy to make such a decision. Only those who have been faced with the immediate choice of similar grim alternatives can understand the weight of the decision that presses on a commander."[4] But Slim does not actually endorse Smyth's choice, and indeed Smyth was dismissed. He never received another command. Brigadier David "Punch" Cowan replaced him in command of the division.

The Official History records that Smyth had wanted to move his troops across the Sittang much earlier, and had been refused. It says: "In view of the great importance of getting 17th Division safely across the Sittang, Hutton might have been wiser, once action had been joined on the Bilin, to give Smyth a free hand."[7]

Aftermath

editThe Japanese could have wiped out the 17th Division, but they did not. They wanted to take Rangoon fast, and the delays involved in a mopping up operation were unacceptable; so they disengaged and headed north in search of another crossing-point. Later on 22 February, survivors of the 17th Division swam and ferried themselves over the Sittang in broad daylight. After smaller actions at the Battle of Pegu and Taukkyan Roadblock, the Japanese went on to take Rangoon unopposed, on 9 March. Fortunately for the survivors of 17th Division, they had dismantled their roadblocks, so those Indians who had escaped Sittang Bridge were able to slip away to the north.[4]

The 17th Division's infantry manpower after Sittang was 3,484—just over 40% of its establishment, though it was already well under-strength before the battle started.[1] Most of its artillery, vehicles and other heavy equipment was lost. Between them, they had 550 rifles, ten Bren guns and 12 tommy guns remaining. Most had lost their boots swimming the river.[3] Still, 17th Division could be replenished and re-equipped, and it was. The artillery losses were of First World War-vintage 18-pounders, and the anti-aircraft provision had only been Lewis guns.[8] 17th Division remained in almost constant contact with the Japanese from December 1941 to July 1944, when it was taken out of the front line at the end of the Battle of Imphal.[9]

According to Louis Allen, "The blowing of the Sittang Bridge with two brigades still on the wrong side of the river was the turning point in the first Burma campaign. Once the Sittang Bridge had gone and the 17th Division rendered powerless, the road to Rangoon was open, and the fate of Burma sealed."[5]

References

editNotes

- ^ a b Liddell Hart 1970, p. 218.

- ^ Liddell Hart 1970, p. 216.

- ^ a b Slim 1956, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Slim 1956, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Allen, Louis (1984). Burma: The Longest War 1941-45. London: Phoenix Press. pp. 1–3, 36–44. ISBN 9781842122600.

- ^ a b c Liddell Hart 1970, p. 217.

- ^ Quoted in Liddell Hart, p.216

- ^ Jeffries & Anderson 2005, p.65.

- ^ Slim 1956, p. 294.

Bibliography

- Liddell Hart, B.H., History of the Second World War. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1970. ISBN 0-306-80912-5.

- Slim, William (1956), Defeat Into Victory. Citations from the Four Square Books 1958 edition which lacks an ISBN, but also available from NY: Buccaneer Books ISBN 1-56849-077-1, Cooper Square Press ISBN 0-8154-1022-0; London: Cassell ISBN 0-304-29114-5, Pan ISBN 0-330-39066-X.

- Jeffreys and Anderson, British Army in the Far East 1941–45. Osprey Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-84176-790-5.