Battle of the Col des Beni Aïcha

The Battle of the Col des Beni Aïcha or Battle of Thenia, which broke out on 19 April 1871, was a battle of the Mokrani Revolt between the Algerian rebels, and the France, which was the colonial power in the region since 1830.[1]

| Battle of the Col des Beni Aïcha (1871) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mokrani Revolt | |||||||

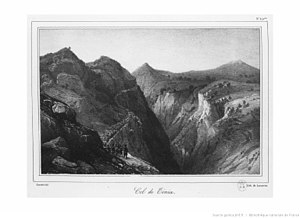

Meraldene valley in Thenia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000 warriors | 2,300 infantrymen | ||||||

Presentation

editAfter the Algerian rebels took control of Palestro on 14 April 1871 after the Battle of Palestro, they wanted to conquer Mitidja and the city of Algiers.

In order to achieve this, Cheikh Mokrani's troops had to bypass the region of Réghaïa via Lower Kabylia, while the spring of 1871 had begun and the Oued Isser was in flood.[2]

The Algerian soldiers went up from Palestro towards the northeast, far from the French garrisons and bivouacs from April 14, 1871, to reach after three days the French colony of Laazib Zamoum on April 17 where they lit wood fires all around this bud of French town.

The French settlers and soldiers began after the Battle of Laazib Zamoum to flee the Issers plain towards Algiers, but the Algerian rebels pursued them towards Bordj Menaïel which was burned during the Battle of Bordj Ménaïel, and similarly during the Battle of the Issers.[3]

Settlement of the Col des Beni Aïcha

editSince 17 May 1837, Colonel Maximilien Joseph Schauenburg and his French soldiers during the Expedition of the Col des Beni Aïcha understood that control of the Col des Beni Aïcha region was crucial for the pacification of eastern Algiers and Kabylia.[4]

Several battles followed one another in this region until 1857 when Kabylia was pacified and the process of human and agricultural colonization began on the sequestered and despoiled land of the natives.[5]

Thus in July 1860, colonist Paul Just, a native of Embrun in the Hautes Alpes, by order of Governor General Patrice de MacMahon, arrived on the Col des Beni Aïcha escorted by a military garrison to found an agricultural concession.

Followed by several other settlers, Paul Just built wooden houses to found the new settlement, hence the name "Wooden Village".[6]

The Col des Beni Aïcha colony quickly became a stage coach, and a café was opened there as well as a wooden chapel and a distillery.[7]

The colonial village thus evolved slowly from 1860 until 1871 when the Pieds-Noirs lived on the meager product of the land and the stopping of travelers at the stage of the diligence.[8]

Battle

editDuring the day of 19 April 1837, the Algerian rebels sprang from the south of the colonial village of Col des Beni Aïcha coming from liberated Palestro, and arriving from the Issers and the heights of the Iflissen, and invaded the entire periphery of the future Menerville then Thenia.[9]

The rebels were commanded in this battle by the Marabout Cheikh Boumerdassi, Cheikh of the Zawiyet Sidi Boumerdassi, and Marabout Cheikh Boushaki, Cheikh of the Zawiyet Sidi Boushaki, who led this Algerian attack against the French colonies in Lower Kabylia.

The rebels of the Iflissen (Flissas), the Issers, the Beni Aïcha, the Beni-Amran and the Khachnas then went to the colonial village of the Col des Beni-Aïcha, from which the settlers were able to escape in time, but who was looted, then set on fire.[10]

Indeed, around noon on 19 April 1871, almost all the French colonists had left the village of the Col des Beni Aïcha, and almost immediately the hamlet was invaded by Algerian rebels.

Cheikh Mokrani, for his part, remained entrenched in liberated Palestro and gave his orders to the rebel troops, while orchestrating and preparing the coveted capture of Algiers.[11]

Counter attack

editAfter the Battle of Alma turned to defeat against the Algerian rebels on 23 April 1871, after the arrival of Colonel Alexandre Fourchault and his French reinforcements from Algiers, the Algerians entrenched themselves at the Col des Beni Aïcha to try to rebound again on Alma.

This is how Colonel Alexandre Fourchault, after having recaptured Alma, walked energetically on the Col des Beni Aïcha which he took up again after sharp clashes on 30 April 1871 with the rebels.

But the Algerians continued until 8 May 1871 to attack the hamlet of Col des Beni Aïcha from all sides, since it is located in a basin surrounded by mountains to the north and south.

Colonel Fourchault had barricaded himself in the burnt and looted village while waiting for reinforcements from General Orphis Léon Lallemand who had gathered in Alma to rush on the Col des Beni Aïcha to free it from the insurrection of Cheikh Mokrani.[12]

Without hesitating a second, and without waiting for reinforcements, General Lallemand left Alma with his head down, and the next day, Tuesday 9 May 1871, at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, his military column was encamped at the Col des Beni Aïcha, which gives access to Great Kabylia.[13]

Punishment of villages

editOn 7 May 1871, Colonel Fourchault was thus instructed to go and burn the villages of the Ammal on the left bank of the Oued Isser, which were abandoned by their inhabitants, and he had to operate with a light column of infantry without bags and cavalry. Left at 11 a.m. to chastise the rebel villages and try to capture the two Sheikhs, he returned to Alma camp at 7 p.m., and had earlier sent a report to General Lallemand where he said that everything was 'had gone for the best.

The two villages (decheras) to which Lallemand wanted to inflict punishment were razed and burned without any gunshot, with the exception of two Algerians who were taken with arms and who were executed on the spot. The skirmishers burned a few gourbis, and the Turcos and Zouaves took charge of the loot collected.[14]

On May 8, 1871, at 5 a.m., General Lallemand's column set out for the Beni-Aïcha pass, following the ridges which form the dividing line between the Isser valley and that of Corso. This road had the advantage of leading to the pass through the ridge line, avoiding the difficulties that would have had to be overcome if we had to force the passage directly. A big stop was made at the fountains of Azela and Tilfaouïn.

The Khachna of the civilian territory had made their submission and sent hostages; they had returned to their villages, where they were not disturbed. Shortly before arriving at the Beni Aïcha pass, General Lallemand had doubts as to whether the villages of Soumâa, Gueddara, Meraldene, Tabrahimt and Azela had really provided hostages.

Colonel Fourchault, who marched in the vanguard, asked the native affairs officer who accompanied him for information on this subject; the latter replied that he was not sure about it, but that General Lallemand was not far behind and that it would be easy to consult him. The people of these villages came out of their houses unarmed and came to meet the column to make an act of submission.

Colonel Fourchault, considering that these villagers were among the rebels who looted the houses of the Beni-Aïcha pass, ordered them to be slashed by the peloton of hunters on horseback who marched as scouts on the village, followed by a group of infantry.

The hunters surrounded the people of Soumâa, Gueddara, Meraldene, Tabrahimt and Azela who had advanced and began to fire rifle shots at them almost at close range. They were so taken by this macabre reception, which they were far from expecting, that they did not even think of fleeing and fifteen of them fell dead one after the other. Fourchault marched on the village which was pillaged and his soldiers shot at the women who were fleeing in the ravines with the men who had not been hit.

One of the villagers who had fallen under the bullets was only wounded and he remained motionless pretending to be dead, and when the shooters went to take off his burnous, he took his course in the ravine and managed to escape, but five other men from the villages were similarly killed, and a woman was also killed while fleeing into the ravine.

After this raid of punishment, the column of Fourchault established its bivouac at the deserted Col des Beni-Aïcha, at 4 o'clock in the afternoon after having traveled 20 kilometers, and it found water there at the fountain of the village and to a fairly abundant spring located above the camp. Orders were given to rally the convoy and the luggage left at the Alma to spend the day of May 9 resting at the Beni Aïcha pass before continuing to hunt down the rebels.[15]

Captures of Cheikhs

editBefore reaching the Col des Beni Aïcha, General Lallemand had given on 8 April 1871 the orders to intercept and capture Cheikh Boumerdassi and Cheikh Mohamed Boushaki in their entrenchments and hiding places in the mountains of Khachna and Ammal.[16][17]

Finally Cheikh Boumerdassi, his brother Abdelkader Boumerdassi, as well as Cheikh Mohamed Boushaki were flushed out and captured before being imprisoned.[18]

Cheikh Mohamed Boumerdassi was deported to New Caledonia in 1874, aged 56 at the time and whose name was Mohamed ben Hamou ben Ali Boumerdassi, with the order number: 130133.[19]

After the complete stifling of this insurrection of Sheikh Mokrani, the orders of sequestration and spoliation of the lands of the Algerian insurgents were promulgated.[20]

If insurgents were then sentenced to the death penalty or to hard labor for life, others were simply deported to New Caledonia after being taken prisoner at Fort Quélern, then transported by the ship La Loire to on board thirty-four Algerian political deportees via the ninth convoy that left the port of Brest on 5 June 1874 and arrived at the port of Nouméa on 16 October 1874.[21]

See also

editExternal links

edit- (fr) Information on the capture of Algiers in 1830 on YouTube

- (fr) The conquest of Algeria: Interview with Ahmed Djebbar on YouTube

- 1- (fr) The conquest of Algeria (1830-1847) on YouTube

- 2- (fr) The conquest of Algeria (1830-1847) on YouTube

- (fr) The conquest of Algeria: Interview with Jacques Frémeaux on YouTube

- (fr) Conquest of Algeria - Marshal Bugeaud on YouTube

Bibliography

editReferences

edit- ^ Rinn, Louis (1891). "Histoire de l'insurrection de 1871 en Algérie".

- ^ "Maximilien Joseph de Schauenburg | Charge du 5e régiment de chasseurs à cheval contre des Cosaques, vers 1805-1807 | Images d'Art" (in French). Art.rmngp.fr. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "Historique Ménerville - Ville — 1830-1962 ENCYCLOPEDIE de L'AFN" (in French). Encyclopedie-afn.org. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "Collection de documents concernant l'Algérie. Dossier 1". culture.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "MENERVILLE - .1871: C'est le soulèvement qui embrasa la Kabylie à la suite des difficultés rencontrées - [PDF Document]". fdocuments.fr.

- ^ "Menerville" (PDF). jeanyvesthorrignac.fr (in French). Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Menerville nos souvenirs, col des Beni aïcha, Thenia, histoire". menerville.free.fr.

- ^ "Algérie - Ménerville — Geneawiki" (in French). Fr.geneawiki.com. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Lettres et carnets de route du commandant Briquelot de 1871 à 1896. ISBN 9782748113990.

- ^ "Revue des deux mondes". 1873.

- ^ Rinn, Louis (1891). "Histoire de l'insurrection de 1871 en Algérie".

- ^ Faucon, Narcisse (1890). "Le livre d'or de l'Algérie: Histoire politique, militaire, administrative; événements et faits principaux; biographie des hommes ayant marqué dans l'armée, les sciences, les lettres, etc., de 1830 à 1889".

- ^ "Les Arabes Martyrs. Étude sur l'insurrection de 1871 en Algérie". 1873.

- ^ L'Insurrection de la Grande Kabylie en 1871 / Par le colonel Robin. 1901.

- ^ L'Insurrection de la Grande Kabylie en 1871 / Par le colonel Robin. 1901.

- ^ Rinn, Louis (1891). "Histoire de l'insurrection de 1871 en Algérie".

- ^ L'Insurrection de la Grande Kabylie en 1871 / Par le colonel Robin. 1901.

- ^ Histoire littéraire de la Nouvelle-Calédonie (1853-2005). 26 March 2014. ISBN 9782811109653.

- ^ Sarda, Gérard (2010). Le procès Konhu en Nouvelle-Calédonie : Une nouvelle affaire Outreau ?. ISBN 9782296113879.

- ^ Lallaoui, Mehdi (1994). Kabyles du Pacifique. ISBN 9782910780005.

- ^ Mailhé, Germaine (1994). Déportations en Nouvelle-Calédonie des communards et des révoltés de la Grande Kabylie (1872 à 1876). ISBN 9782738427960.