The Battle of Rain[a] took place on 15 April 1632 near Rain in Bavaria during the Thirty Years' War. It was fought by a Swedish army under Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, and a Catholic League force led by Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly. The battle resulted in a Swedish victory, while Tilly was severely wounded and later died of his injuries.

| Battle of Rain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Thirty Years' War | |||||||

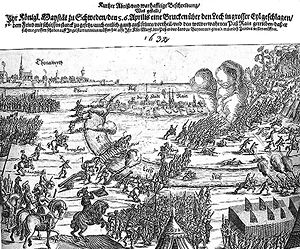

Battle of Rain (engraving) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 37,500 men, 72 guns [1] | c. 22,000 men, 20 guns[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000 killed or wounded |

2,000 killed or wounded 1,000 captured | ||||||

Outnumbered and with many inexperienced troops, Tilly built defensive works along the River Lech, centred on the town of Rain, hoping to delay Gustavus long enough for Imperial reinforcements under Albrecht von Wallenstein to reach him. On 14 April, the Swedes bombarded the defences with artillery, then crossed the river the next day, inflicting nearly 3,000 casualties, including Tilly. On 16th, Maximilian of Bavaria ordered a retreat, abandoning his supplies and guns.

Despite this victory, the Swedes had been drawn away from their bases in Northern Germany and when Maximilian linked up with Wallenstein found themselves besieged in Nuremberg. This led to the largest battle of the war on 3 September, when an assault on the Imperial camp outside the town was bloodily repulsed.

Background

editSwedish intervention in the Thirty Years' War began in June 1630 when nearly 18,000 troops under Gustavus Adolphus landed in Pomerania, financed by French subsidies. Supported by Saxony and Brandenburg-Prussia, victory at Breitenfeld in September 1631 gave Gustavus control over much of north and central Germany.[2] While Elector John George invaded Habsburg lands in Bohemia, Gustavus prepared to attack Austria, while his subordinate Gustav Horn advanced into Franconia.[3]

When Horn occupied the Bavarian town of Bamberg in February 1632, Tilly marched north from Nördlingen with 22,000 men, and briefly recaptured it on 9 March. He was too weak to follow up this success and withdrew to Ingolstadt, which controlled a major bridge over the Danube. However, fearing the impact of Tilly's advance on the morale of his German allies, Gustavus abandoned plans to invade Austria. Instead, he moved into Bavaria from his winter quarters in Mainz, where by combining his own forces with those led by Horn, Johan Banér, and William, Duke of Saxe-Weimar, he assembled around 37,500 men and 72 guns.[4]

The Swedes entered Nuremberg on 31 March, then captured Donauwörth on 6 April, near where Tilly had established a defensive line along the River Lech. His main force of 22,000 was entrenched around Rain, with a detachment of 5,000 covering another crossing at Augsburg (see Map). Although this meant Gustavus could outflank these positions by passing south of Augsburg, Tilly hoped this would provide time for the main Imperial army under Albrecht von Wallenstein to reach him.[1]

At this point, the Lech river divided into a number of parallel, fast flowing streams, each about 60 to 80 metres wide; the bridge at Rain had been destroyed by Tilly, who placed his inexperienced troops in a strong redoubt with 20 guns, making it a formidable challenge for an attacker. The only other practical route was about five kilometres south of Rain, where there was an island in the middle of the Lech. Bridging this obstacle is considered to be one of Gustavus' greatest military achievements.[5]

Battle

editDuring 13 April, Lennart Torstensson supervised the construction of Swedish artillery positions opposite Rain, creating three batteries of 24 guns each. The next day, he opened fire on Tilly's redoubt while Gustavus deployed his troops near the river bank, making it seem he intended an assault. However, this was only a feint, intended to distract their opponents while they gathered boats and materials to build a pontoon bridge over to the island.[1]

On the morning of 15th, three hundred Finnish Hakkapeliitta troops crossed over to the Bavarian side of the river. Having done so, they then dug earthworks for batteries which protected the rest of Gustavus' army as they followed.[6] Tilly immediately despatched troops to engage the Swedes and a fierce firefight developed as they tried to push them back. However, Gustavus had sent an additional 2,000 cavalry to ford the river two kilometres further north of Rain. These now circled round the redoubt and took the troops defending it in the flank. Tilly's right thigh was shattered early in the battle; he was taken unconscious to the rear and died two weeks later, [7] while his second in command, Johann von Aldringen, was temporarily blinded minutes later.[8]

Maximilian of Bavaria now assumed command and ordered an immediate retreat, covered by his cavalry under Scharffenstein. Both sides suffered around 2,000 casualties each, with the Swedes capturing another 1,000. Although Maximilian was forced to abandon his baggage and artillery, most of his army escaped, helped by a storm and high winds which blocked roads and delayed pursuit.[9]

Aftermath

editMaximilian reinforced his garrison at Ingolstadt, which repulsed a Swedish attack on 3 May, then withdrew north of the Danube, leaving Bavaria open to the Swedish army. The country was extensively pillaged, while Gustavus made a triumphal entry into Munich on 17 May, confiscating the ducal art collection and capturing over 100 pieces of artillery; it was another three years before Maximilian re-entered his capital.[10] On the other hand, the Swedes were now at the end of long and extremely vulnerable supply lines, while Bavarian peasants waged a bitter guerrilla war in the countryside against the invaders plundering their lands.[8]

Meanwhile Wallenstein raised an Imperial army of 65,000, which he used to expel the Saxons from Bohemia; concerned Saxony might make a separate peace and leave him isolated, Gustavus now summoned his German allies to Nuremberg. As he did so, Wallenstein took 30,000 troops and marched into Bavaria to link up with Maximilian advancing north from Ingoldstadt and on 11 July the two forces met up at Schwabach (see Map above).[11] Gustavus retreated to Fürth just outside Nuremberg where he was besieged by the combined Imperial-Bavarian army, leading to the Battle of the Alte Veste in early September.[12]

See also

editFootnotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Guthrie 2001, p. 166.

- ^ Wedgwood 1938, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Wilson 2009, pp. 494–495.

- ^ Guthrie 2001, p. 165.

- ^ Wilson 2009, p. 498.

- ^ Kankaanpää 2016, p. 790.

- ^ Harrison 2021, p. 114.

- ^ a b Wilson 2009, p. 499.

- ^ Wedgwood 1938, p. 315.

- ^ Parker 1984, p. 116.

- ^ Wedgwood 1938, p. 320.

- ^ Wilson 2009, p. 501.

Sources

edit- Guthrie, William (2001). Battles of the Thirty Years War: From White Mountain to Nordlingen, 1618–1635. Praeger. ISBN 978-0313320286.

- Harrison, Dick (2021). Sveriges stormaktstid (in Swedish). Historiska Media. ISBN 978-91-7789-624-1.

- Kankaanpää, Matti J (2016). Suomalainen ratsuväki Ruotsin ajalla (in Finnish). T:mi Toiset aijat. ISBN 978-952-99106-9-4.

- Parker, Geoffrey (1984). The Thirty Years' War (1997 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-12883-4.

- Wedgwood, CV (1938). The Thirty Years War (2005 ed.). New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1590171462.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2009). Europe's Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years War. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9592-3.