The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and the United Kingdom and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2023) |

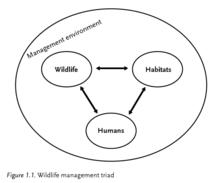

Wildlife management is the management process influencing interactions among and between wildlife, its habitats and people to achieve predefined impacts.[1][2][3] It attempts to balance the needs of wildlife with the needs of people using the best available science. Wildlife management can include wildlife conservation, population control, gamekeeping, wildlife contraceptive and pest control.[4]

Wildlife management aims to halt the loss in the Earth's biodiversity,[5][6] by taking into consideration ecological principles such as carrying capacity, disturbance and succession, and environmental conditions such as physical geography, pedology and hydrology.[7][8][9][10] Most wildlife biologists are concerned with the conservation and improvement of habitats; although rewilding is increasingly being undertaken.[11] Techniques can include reforestation, pest control, nitrification and denitrification, irrigation, coppicing and hedge laying.

Gamekeeping is the management or control of wildlife for the well-being of game and may include the killing of other animals which share the same niche or predators to maintain a high population of more profitable species, such as pheasants introduced into woodland. Aldo Leopold defined wildlife management in 1933 as the art of making land produce sustained annual crops of wild game for recreational use.[12]

History

editThe history of wildlife management begins with the game laws, which regulated the right to kill certain kinds of fish and wild animal (game). In Britain game laws developed out of the forest laws, which in the time of the Norman kings were very oppressive. Under William the Conqueror, it was as great a crime to kill one of the king's deer as to kill one of his subjects. A certain rank and standing, or the possession of a certain amount of property, were for a long time qualifications indispensably necessary to confer upon anyone the right of pursuing and killing game.

United Kingdom

editThe late 19th century saw the passage of the first pieces of wildlife conservation legislation and the establishment of the first nature conservation societies. The Sea Birds Preservation Act of 1869 was passed in the United Kingdom as the first nature protection law in the world[13] after extensive lobbying from the Association for the Protection of Sea-Birds.[14]

The Game Act 1831 (1 & 2 Will. 4. c. 32) protected game birds by establishing close seasons when they could not be legally taken. The act made it lawful to take game only with the provision of a game license and provided for the appointment of gamekeepers around the country. The purposes of the law was to balance the needs for preservation and harvest and to manage both environment and populations of fish and game.[15]

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds was founded as the Plumage League in 1889 by Emily Williamson at her house in Manchester[16] as a protest group campaigning against the use of great crested grebe and kittiwake skins and feathers in fur clothing. The group gained popularity and eventually amalgamated with the Fur and Feather League in Croydon to form the RSPB.[17] The Society attracted growing support from the suburban middle-classes as well as support from many other influential figures, such as the ornithologist Professor Alfred Newton.[16]

The National Trust formed in 1895 with the manifesto to "...promote the permanent preservation, for the benefit of the nation, of lands, ...to preserve (so far practicable) their natural aspect." On 1 May 1899, the Trust purchased two acres of Wicken Fen with a donation from the amateur naturalist Charles Rothschild, establishing the first nature reserve in Britain.[18] Rothschild was a pioneer of wildlife conservation in Britain, and went on to establish many other nature reserves, such as one at Woodwalton Fen, near Huntingdon, in 1910.[19] During his lifetime he built and managed his estate at Ashton Wold[20] in Northamptonshire to maximise its suitability for wildlife, especially butterflies. Concerned about the loss of wildlife habitats, in 1912 he set up the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves, the forerunner of The Wildlife Trusts partnership.

During the society's early years, membership tended to be made up of specialist naturalists and its growth was comparatively slow. The first independent Trust was formed in Norfolk in 1926 as the Norfolk Naturalists Trust, followed in 1938 by the Pembrokeshire Bird Protection Society which after several subsequent changes of name is now the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales and it was not until the 1940s and 1950s that more Naturalists' Trusts were formed in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Leicestershire and Cambridgeshire. These early Trusts tended to focus on purchasing land to establish nature reserves in the geographical areas they served.

In the later 20th century, wildlife management is undertaken by several organizations including government bodies such as the Forestry Commission, Charities such as the RSPB and The Wildlife Trusts and privately hired gamekeepers and contractors. Legislation has also been passed to protect wildlife such as the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. The UK government also give farmers subsidies through the Countryside Stewardship Scheme to improve the conservation value of their farms.

United States

editEarly game laws were enacted in the United States in 1839 when Rhode Island closed the hunting season for white-tailed deer from May to November. Other regulations during this time focused primarily on restricting hunting. At this time, lawmakers did not consider population sizes or the need for preservation or restoration of wildlife habitats.[21]

The profession of wildlife management was established in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s by Aldo Leopold and others who sought to transcend the purely restrictive policies of the previous generation of conservationists, such as anti-hunting activist William T. Hornaday. Leopold and his close associate Herbert Stoddard, who had both been trained in scientific forestry, argued that modern science and technology could be used to restore and improve wildlife habitat and thus produce abundant "crops" of ducks, deer, and other valued wild animals.[22]

The institutional foundations of the profession of wildlife management were established in the 1930s, when Leopold was granted the first university professorship in wildlife management (1933, University of Wisconsin, Madison), when Leopold's textbook 'Game Management' was published (1933), when The Wildlife Society was founded, when the Journal of Wildlife Management began publishing, and when the first Cooperative Wildlife Research Units were established. Conservationists planned many projects throughout the 1940s. Some of which included the harvesting of female mammals such as deer to decrease rising populations. Others included waterfowl and wetland research. The Fish and Wildlife Management Act was put in place to urge farmers to plant food for wildlife and to provide cover for them.[22]

In 1937, the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (also known as the Pittman-Robertson Act) was passed in the U.S.. This law was an important advancement in the field of wildlife management. It placed a 10% tax on sales of guns and ammunition. The funds generated were then distributed to the states for use in wildlife management activities and research. This law is still in effect today.[23]

Wildlife management grew after World War II with the help of the GI Bill and a postwar boom in recreational hunting. An important step in wildlife management in the United States national parks occurred after several years of public controversy regarding the forced reduction of the elk population in Yellowstone National Park.[citation needed] In 1963, United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall appointed an advisory board to collect scientific data to inform future wildlife management. In a paper known as the Leopold Report, the committee observed that culling programs at other national parks had been ineffective, and recommended active management of Yellowstone's elk population.[24]

Elk overpopulation in Yellowstone is thought by many wildlife biologists, such as Douglas Smith, to have been primarily caused by the extirpation of wolves from the park and surrounding environment. After wolves were removed, elk herds increased in population, reaching new highs during the mid-1930s. The increased number of elk resulted in overgrazing in parts of Yellowstone. Park officials decided that the elk herd should be managed. For approximately thirty years, the park elk herds were culled: Each year some were captured and shipped to other locations, a certain number were killed by park rangers, and hunters were allowed to take more elk that migrated outside the park. By the late 1960s the herd populations dropped to historic lows (less than 4,000 for the Northern Range herd). This caused outrage among both conservationists and hunters. The park service stopped culling elk in 1968. The elk population then rebounded. Twenty years later there were 19,000 elk in the Northern Range herd, a historic high.[25]

Since the tumultuous 1970s, when animal rights activists and environmentalists began to challenge some aspects of wildlife management, the profession has been overshadowed by the rise of conservation biology. Although wildlife managers remain central to the implementation of the Endangered Species Act and other wildlife conservation policies, conservation biologists have shifted the focus of conservation away from wildlife management's concern with the protection and restoration of single species and toward the maintenance of ecosystems and biodiversity. In the United States, wildlife management practices are implemented by a governmental agency, such as the Endangered Species Act.[25]

Types of wildlife management

editCustodial management is preventive or protective. The aim is to minimize external influences on the population and its habitat. It is appropriate in a national park where one of the stated goals is to protect ecological processes. It is also appropriate for conservation of a threatened species where the threat is of external origin rather than being intrinsic to the system. Feeding of animals by visitors is discouraged.[26][27]

Manipulative management acts on a population, either changing its numbers by direct means or influencing numbers by the indirect means of altering food supply, habitat, density of predators, or prevalence of disease. This is appropriate when a population is to be harvested, or when it slides to an unacceptably low density or increases to an unacceptably high level. Such densities are inevitably the subjective view of the land owner, and may be disputed by animal welfare interests.[28]

Pest control is the control of real or perceived pests and can be used for the benefit of wildlife, farmers, gamekeepers or human safety.

Hunting limitations

editWildlife management studies, research and lobbying by interest groups help designate times of the year when certain wildlife species can be legally hunted, allowing for surplus animals to be removed. In the United States, hunting season and bag limits are determined by guidelines set by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for migratory game such as waterfowl and other migratory gamebirds. The hunting season and bag limits for state regulated game species such as deer are usually determined by State game Commissions, which are made up of representatives from various interest groups, wildlife biologists, and researchers.[29]

Open season is when wildlife is allowed to be hunted by law and is usually not during the breeding season. Hunters may be restricted by sex, age or class of animal, for instance there may be an open season for any male deer with 4 points or better on at least one antler. Closed season is when wildlife is protected from hunting and is usually during its breeding season. Closed season is enforced by law, any hunting during closed season is punishable by law and termed as illegal hunting or poaching. Open and closed season on deer in the United Kingdom is legislated for in the Deer Act.[30][31]

In wildlife management one of the conservation principles is that the weapon used for hunting should be the one that causes the least suffering to the animal and is sufficiently effective so that it hits the target. Given State and Local laws, types of weapon can also vary depending on type, size, sex of game and also the geographical layout of that specific hunting area.

Impact on ecosystems

editHabitat destruction and fragmentation are major drivers of biodiversity loss in the United Kingdom,[32] however landowners that participate in field sports, particularly hunting and shooting, are more likely to conserve and reinstate woodlands[33] and hedgerows[34] because they are used by quarry species. A study in 2003 showed that they are around 2.5 times more likely to plant new woodlands than landowners without game or hunting interests, and also conserve a far greater woodland area.[33]

Landowners undertake management measures to improve habitats for quarry species, including shrub planting, coppicing[35] and skylighting[36] to encourage understory growth. Roger Draycott of the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust has reported the conservation benefits of game management schemes in the UK, including woodlands with denser undergrowth and higher abundances of native birds.[37] However, overall evidence that game shooting is beneficial to wider biodiversity has been inconclusive: high densities of game birds are known to negatively impact ecosystems, resulting in shorter grassland vegetation,[38] lower floral diversity in semi-natural woodlands,[39] fewer saplings in hedgerows leading from such woodlands,[40] and reductions in arthropod biomass attributable to predation.

The rearing of both wild and released game birds requires the provision of food and shelter during the winter months,[41] and to achieve this landowners plant cover crops. Generally species such as maize or quinoa, these are planted in strips alongside arable land. Cover crops are also utilised by a variety of nationally declining farmland birds such as linnets and finches,[42][43][44] providing valuable food resources and refuge from predators.[45]

Prior to the Hunting Act, fox hunting also provided a major incentive for woodland conservation and management throughout England and Wales, with higher species diversity and abundance of plants and butterflies found in woodlands managed for foxes according to a survey of mounted hunts in 2006, verified by The Council of Hunting Associations.[46]

Opposition

editThe control of wildlife through killing and hunting has created an opposition to hunting by animal rights and animal welfare activists.[47] Critics object to the real or perceived cruelty involved in some forms of wildlife management. They also argue against the deliberate breeding of certain animals by environmental organizations—who hunters pay money to kill—in pursuit of profit.[48] Additionally, they draw attention to the attitude that it is acceptable to kill animals in the name of ecosystem or biodiversity preservation, yet it is seen as unacceptable to kill humans for the same purpose; asserting that such attitudes are a form of discrimination based on species-membership i.e. speciesism.[49][50]

Environmentalists have also opposed hunting where they believe it is unnecessary or will negatively affect biodiversity.[51] Critics of game keeping note that habitat manipulation and predator control are often used to maintain artificially inflated populations of valuable game animals (including introduced exotics) without regard to the ecological integrity of the habitat.[52][53]

Gamekeepers in the UK claim it to be necessary for wildlife conservation as the amount of countryside they look after exceeds by a factor of nine the amount in nature reserves and national parks.[54]

References

edit- ^ Decker, Daniel J.; Riley, Shawn J. (Shawn James); Siemer, William F. (2012). Human dimensions of wildlife management (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4214-0654-1. OCLC 778244877.

- ^ Sinclair, Anthony R. E.; Fryxell, John M.; Caughley, Graeme (2006). Wildlife ecology, conservation, and management (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4051-0737-2. OCLC 58526307.

- ^ Raj, A. J.; Lal, S. B. (2013). Forestry Principles and Applications. Jodhpur: Scientific Publishers (India). p. 359. ISBN 978-93-8623774-3. OCLC 972943172.

- ^ Potter, Dale R.; Kathryn M. Sharpe; John C. Hendee (1973). Human Behavior Aspects Of Fish And Wildlife Conservation - An Annotated Bibliography (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. p. 290.

- ^ James, Frances C. (1980-07-11). "Ecological Recommendations: Conservation Biology. An Evolutionary-Ecological Perspective". Science. 209 (4453): 267–268. doi:10.1126/science.209.4453.267.b. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Soulé, Michael E. (1985-12-01). "What is Conservation Biology?: A new synthetic discipline addresses the dynamics and problems of perturbed species, communities, and ecosystems". BioScience. 35 (11): 727–734. doi:10.2307/1310054. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ^ Soule, Michael E. (1986). Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity. Sinauer Associates. p. 584. ISBN 9780878937950.

- ^ Hunter, M. L. (1996). Fundamentals of Conservation Biology. Blackwell Science Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts., ISBN 0-86542-371-7.

- ^ Groom, M.J., Meffe, G.K. and Carroll, C.R. (2006) Principles of Conservation Biology (3rd ed.). Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. ISBN 0-87893-518-5

- ^ van Dyke, Fred (2008). Conservation Biology: Foundations, Concepts, Applications, 2nd ed. Springer Verlag. p. 478. ISBN 978-1-4020-6890-4.

- ^ Torres, Aurora; Fernández, Néstor; zu Ermgassen, Sophus; Helmer, Wouter; Revilla, Eloy; Saavedra, Deli; Perino, Andrea; Mimet, Anne; Rey-Benayas, José M.; Selva, Nuria; Schepers, Frans (2018-12-05). "Measuring rewilding progress". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170433. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0433. PMC 6231071. PMID 30348877.

- ^ Leopold, Aldo (1996). Game management. ISBN 81-85019-54-1. OCLC 971482354.

- ^ G. Baeyens, M. L. Martinez (2007). Coastal Dunes: Ecology and Conservation. Springer. p. 282.

- ^ "Protecting seabirds at Bempton Cliffs". 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Wildlife Conservation and Management" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on Dec 30, 2006.

- ^ a b "Milestones". RSPB. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ "History of the RSPB". RSPB. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ "Wicken Fen National Nature Reserve". Wicken Fen..

- ^ Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire and Peterborough

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1961). The Buildings of England – Northamptonshire. London and New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 94–5. ISBN 978-0-300-09632-3.

- ^ Bolen, Eric G.; Robinson, William L. (2003). Wildlife ecology and management (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-13-066250-7. OCLC 49558956.

- ^ a b Mahoney, Shane P., ed. (2019). The North American model of wildlife conservation. Wildlife management and conservation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-3280-9.

- ^ Ryder, Thomas J. (2018). State wildlife management and conservation. Wildlife management and conservation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins university press. ISBN 978-1-4214-2446-0.

- ^ Leopold, A. Starker, et al. 1963. "The Goal of Park Management in the United States". Wildlife Management in the National Parks. National Park Service. Retrieved on September 19, 2009.

- ^ a b Silvy, Nova J. (2020). The wildlife techniques manual (8 ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins university press. ISBN 978-1-4214-3669-2.

- ^ McComb, Brenda C. (2015). Wildlife habitat management: concepts and applications in forestry (2 ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-4398-7856-9.

- ^ Tallamy, Douglas W. (2019). Nature's best hope: a new approach to conservation that starts in your yard. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-1-60469-900-5. OCLC 1078889529.

- ^ Krausman, Paul R.; Cain, James W., eds. (2013). Wildlife management and conservation: contemporary principles and practices. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, published in affiliation with The Wildlife Society. ISBN 978-1-4214-0986-3.

- ^ Salzman, James; Thompson, Barton H. (2019). Environmental law and policy. Concepts and insights series (5 ed.). St. Paul, MN: Foundation Press. ISBN 978-1-68328-790-2.

- ^ "Deer Act". Legislation.gov.uk. 1991.

- ^ "Deer (Scotland) Act". Legislation.gov.uk. 1996.

- ^ "Lost life: England's lost and threatened species - NE233". Natural England. 2010-03-10.

- ^ a b Oldfield, T. E. E.; Smith, R. J.; Harrop, S. R.; Leader-Williams, N. (2003-05-29). "Field sports and conservation in the United Kingdom". Nature. 423 (6939): 531–533. doi:10.1038/nature01678. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12774120.

- ^ Draycott, Roger A. H.; Hoodless, Andrew N.; Cooke, Matthew; Sage, Rufus B. (2012-02-01). "The influence of pheasant releasing and associated management on farmland hedgerows and birds in England". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 58 (1): 227–234. doi:10.1007/s10344-011-0568-0. ISSN 1439-0574.

- ^ Robertson, P.A. (1992). "Woodland management for pheasants" (PDF). Forestry Commission Archive.

- ^ Ludolf, I.C.; Robertson, P.A.; Woodburn, M.I.A. (1989). "Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust". Biological Habitat Conservation. London: Belhaven Press. pp. 312–327.

- ^ Draycott, Roger A. H.; Hoodless, Andrew N.; Sage, Rufus B. (2008). "Effects of pheasant management on vegetation and birds in lowland woodlands". Journal of Applied Ecology. 45 (1): 334–341. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01379.x. ISSN 0021-8901.

- ^ Callegari, Sarah E.; Bonham, Emma; Hoodless, Andrew N.; Sage, Rufus B.; Holloway, Graham J. (2014-10-01). "Impact of game bird release on the Adonis blue butterfly Polyommatus bellargus (Lepidoptera Lycaenidae) on chalk grassland". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 60 (5): 781–787. doi:10.1007/s10344-014-0847-7. ISSN 1439-0574.

- ^ Sage, Rufus B.; Ludolf, Clare; Robertson, Peter A. (2005-03-01). "The ground flora of ancient semi-natural woodlands in pheasant release pens in England". Biological Conservation. 122 (2): 243–252. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.07.014. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Sage, R. B.; Woodburn, M. I. A.; Draycott, R. A. H.; Hoodless, A. N.; Clarke, S. (2009-07-01). "The flora and structure of farmland hedges and hedgebanks near to pheasant release pens compared with other hedges". Biological Conservation. 142 (7): 1362–1369. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2009.01.034. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Parish, David M. B.; Sotherton, Nicolas W. (2004-12-01). "Game crops as summer habitat for farmland songbirds in Scotland". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 104 (3): 429–438. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2004.01.037. ISSN 0167-8809.

- ^ Stoate, Chris; Szczur, John; Aebischer, Nicholas J. (2003). "Winter use of wild bird cover crops by passerines on farmland in northeast England". Bird Study. 50 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1080/00063650309461285. ISSN 0006-3657.

- ^ Henderson, I. G; Vickery, J. A; Carter, N (2004-06-01). "The use of winter bird crops by farmland birds in lowland England". Biological Conservation. 118 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2003.06.003. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Sage, Rufus B.; Parish, David M. B.; Woodburn, Maureen I. A.; Thompson, Peter G. L. (2005-12-01). "Songbirds using crops planted on farmland as cover for game birds". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 51 (4): 248–253. doi:10.1007/s10344-005-0114-z. ISSN 1439-0574.

- ^ Stoate, C. (2002-04-01). "Multifunctional use of a natural resource on farmland: wild pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) management and the conservation of farmland passerines". Biodiversity & Conservation. 11 (4): 561–573. doi:10.1023/A:1015564806990. ISSN 1572-9710.

- ^ Ewald, J. A.; Callegari, S. E.; Kingdon, N. G.; Graham, N. A. (2006-12-01). "Fox-hunting in England and Wales: its contribution to the management of woodland and other habitats". Biodiversity & Conservation. 15 (13): 4309–4334. doi:10.1007/s10531-005-3739-z. ISSN 1572-9710.

- ^ Gamborg, Christian; Palmer, Clare; Sandoe, Peter (2012). "Ethics of Wildlife Management and Conservation: What Should We Try to Protect?". Nature Education Knowledge. 3 (10): 8.

- ^ "Hunting". PETA. 2010-06-24. Retrieved 2019-10-11.

- ^ "Hunting". Animal Ethics. 2016-03-29. Retrieved 2019-10-11.

- ^ Carson, Rachel (1962). Silent spring (40 ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-24906-0. OCLC 50751491.

- ^ "Does Hunting Help or Hurt the Environment?". Scientific American. 2009-11-10. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ Salem, Deborah J.; Rowan, Andrew N.; Humane Society of the United States, eds. (2003). The state of the animals II, 2003. Public policy series. Washington, D.C: Humane Society Press. ISBN 978-0-9658942-7-2.

- ^ Juniper, Tony, ed. (2019). The ecology book. Big ideas simply explained. New York, New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4654-7958-7. OCLC 1044554389.

- ^ National Gamekeepers' Organisation Charitable Trust

External links

editMedia related to Wildlife management at Wikimedia Commons