Beatus of Liébana (Spanish: Beato; c. 730 – c. after 785) was a monk, theologian, and author of the Commentary on the Apocalypse, mostly a compendium of previous authorities' views on the biblical Book of Revelation or Apocalypse of John. This had a local influence, mostly in the Iberian Peninsula, up to about the 13th century, but is today remembered mainly for the 27 surviving manuscript copies that are heavily illustrated in an often spectacular series of miniatures that are outstanding monuments of Mozarabic art. Examples include the Morgan Beatus and Saint-Sever Beatus; these are covered further at the article on the book. Most unusually for a work of Christian theology, it appears that Beatus always intended his book to be illustrated, and he is attributed with the original designs, and possibly the execution, of the first illustrations, which have not survived.[2]

Saint Beatus | |

|---|---|

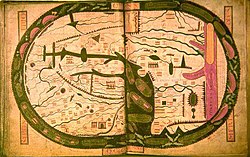

The world map from the Saint-Sever Beatus. Painted c. 1050 as an illustration to Beatus's work at the Abbey of Saint-Sever in Aquitaine. | |

| Born | c. 730 |

| Died | after 785 |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church, Orthodox Church |

| Feast | February 19 |

Aside from his work, almost nothing is known about Beatus. He was a monk and probably an abbot at the monastery of Santo Toribio de Liébana in the Kingdom of Asturias, the only region of Spain remaining outside of Muslim control. It is thought that he was probably one the large number of monastic refugees who moved north, to lands remaining under Christian rule after the Muslim conquest of southern and central Spain.[3][4] Beatus appears to have been well known by his contemporaries. He was a correspondent with the notable Christian scholar, Alcuin, and a confidant of queen Adosinda, daughter of Alfonso I of Asturias and wife of Silo of Asturias.[5][6] He was present when Adosinda took her vows as a nun in 785,[7] the last record we have of his life. A supposed biography, the Life of Beatus, has been identified as a 17th-century fraud with no historical value.[5][4]

For Beatus, the observation and reading of such works was a sacred action, akin to communion. Beatus treats the reading of the book as the same as the body, and so by reading the book, the reader is one with Christ.[8] He also led the opposition against a Spanish variant of Adoptionism, the heretical belief that Christ was the son of God by adoption, an idea first propounded in Spain by Elipandus, the bishop of Toledo.

An important, and enduring, influence of Beatus seems to be that he established the idea in Spain that Iberia had been converted by the Apostle James.[9]

Apocalypse commentary

editHe is best remembered today as the author of the Commentary on the Apocalypse, written in 776, then revised in 784 and again in 786.[10] The Commentary is a work of erudition but without great originality, made up principally of extracts from the texts of Church authorities including Augustine of Hippo, Tyconius, Ambrose, Irenaeus, and Isidore of Seville. He relied most heavily on the lost Commentary by Tyconius, whose writing provided Beatus with much of the text for his work.[11] Later versions added the commentary by Jerome on the Book of Daniel,and other material to most manuscripts.[4]

The Commentary was popular in Iberia during the Middle Ages and survives in at least 32 manuscripts (usually called a Beatus) from the 9th through the 13th centuries.[12] No contemporary copies of Beatus's work have survived. Not all of the manuscripts are complete, and some exist only in fragmentary form. Twenty-six of these manuscripts are lavishly decorated and have been recognized as some of the best examples of the Mozarabic style of illumination.[10][13][5]

Beatus map

editOf special interest to cartographers is a world map included in the second book of the Commentary. Unlike most medieval maps which showed only the three known continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa, the Beatus map also displayed a fourth, unknown continent. The original purpose of the map was evangelical, displaying the apostles preaching in every part of the world, including the fourth continent. The original map has been lost but several copies have survived, all featuring an eastern orientation and paradise with four rivers flowing from it.[14]

Adoptionism controversy

editBeatus was a vocal opponent of a Spanish variant of adoptionism, the belief that Christ was the son of God by adoption, an idea first put forward by Elipandus, Bishop of Toledo and Bishop Felix of Urgell on the Iberian Peninsula. Elipandus and Felix declared that Jesus, in respect to his human nature, was the adopted son of God by God's grace, thus emphasizing the distinction between the divinity and the humanity of Christ. Beatus and other opponents of adoptionism, such as Alcuin and Paulinus II of Aquileia, feared that this view would so divide the person of the Savior that the reality of the incarnation would be lost. In addition, many theologians were concerned that this adoptionism was a new version of the Nestorianism advanced by Nestorius.[15]

In 794, Elipandus attacked Beatus in a letter to the bishops of Gaul, calling Beatus a pseudo-prophet and accusing him of having falsely announced the imminent end of the world. In response to the controversy, Charlemagne called together the Council of Frankfurt in 794. The assembled bishops condemned adoptionism as a heresy and in 798, Pope Leo III confirmed the heresy of adoptionism.[10]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Beatus of Liébana. "Monstrous Cavalry, Beatus de Saint-Sever". Commentary on the Apocalypse.

- ^ Williams (2017), 23-25

- ^ Williams (2017), 22

- ^ a b c Vivancos Gomez.

- ^ a b c Collins 2000, p. 225.

- ^ Cavadini 1993, p. 45.

- ^ Williams (2017), 21

- ^ Brown, Catherine (May 2009). "Love Letters from Beatus of Liébana to Modern Philologists". Modern Philology. 106 (4): 579–600 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Williams (2017), 21-22

- ^ a b c Wolf 2003, p. 155.

- ^ Cavadini 1993, p. 46.

- ^ Williams 1992, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Piera 2010.

- ^ Woodward 1987, pp. 303–304.

- ^ González 2010, pp. 109–111.

Bibliography

edit- Beazley, Charles Raymond (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). p. 584.

- Cavadini, John C. (1993). The Last Christology of the West: Adoptionism in Spain and in Gaul 785 - 817. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3186-1.

- Collins, Roger (2000). The Arab Conquest of Spain: 710 - 797. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19405-7.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2012). Apocalypse: The Illustrated Book of Revelation. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B008WAK9SS

- González, Justo L. (2010). A History of Christian Thought Volume II: From Augustine to the Eve of the Reformation. Abingdon Press. pp. 109–111. ISBN 9781426721915.

- Piera, Montserrat (2010). "Beatus of Liébana (d. 798)". The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Oxford University Press.

- Vivancos Gomez, Miguel C. "Beato de Liébana". Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish).

- Williams, John; Shailor, Barbara A. (1991). A Spanish Apocalypse: the Morgan Beatus manuscript. New York: G. Braziller the Pierpont Morgan Library. ISBN 978-0-8076-1262-0.

- Williams, John (1992). "Purpose and Imagery in the Apocalypse Commentary of Beatus of Liébana". In Emmerson, Richard Kenneth (ed.). The Apocalypse in the Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-2282-9.

- Williams, John (1997). "Isidore, Orosius and the Beatus Map". Imago Mundi. 49: 7–32. ISSN 0308-5694. JSTOR 1151330.

- Williams, John (2017), “Visions of the End in Medieval Spain: Introductory Essay.” In Visions of the End in Medieval Spain, edited by Therese Martin, 21–66. Amsterdam University Press, 2017, JSTOR free access. This is Williams' final summary, several years after his main work.

- Wolf, Kenneth B. (2003). "Beatus of Liébana". In Gerli, E. Michael (ed.). Medieval Iberia : An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93918-6.

- Woodward, David (1987). "18 - Medieval Mappaemundi". Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31633-8.