The Beheadings of Moca (Spanish: Degüello de Moca; French: Décapitation de Moca; Haitian Creole: Masak nan Moca)[3] was a massacre that took place in Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) in April 1805 when the invading Haitian army attacked civilians as ordered by Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe, during their retreat to Haiti after the failed attempt to end French rule in Santo Domingo. The event was narrated by survivor Gaspar Arredondo y Pichardo in his book Memoria de mi salida de la isla de Santo Domingo el 28 de abril de 1805 (Memory of my departure from the island of Santo Domingo on April 28, 1805), which was written nearly 40 years after the massacre is said to have taken place.[4][5] The broader invasion was part of a series of Haitian invasions into Santo Domingo, and occurred after the return from the Siege of Santo Domingo (1805).[6] Haitian historian Jean Price-Mars wrote that the troops killed the inhabitants of the targeted settlements irrespective of race.[7]

| Beheadings of Moca | |

|---|---|

| Part of Siege of Santo Domingo (1805) | |

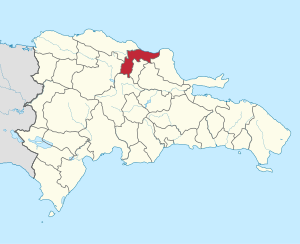

Espaillat in the Dominican Republic | |

| Location | Santo Domingo |

| Date | 3 April 1805 – 28 April 1805 |

| Target | Jean-Louis Ferrand and his troops, Dominicans. |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Weapons | Bayonets, machetes, axes, firearms, swords |

| Deaths | 500 (at Moca),[1] 400 at Santiago[2] |

| Victims | Civilians of Santo Domingo |

| Perpetrators | Army of the First Empire of Haiti |

| Motive | Reprisal[1][2] |

The raids, carried out by the Haitian invasion force, were headed by Henri Christophe and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who were present during the actions. Municipalities of Santo Domingo (Monte Plata, Cotuí, La Vega, Santiago, Moca, San Jose de las Matas, Monte Cristi, and San Juan de la Maguana) were burned, with reported massacres in Santiago and Moca and the killing of 500 civilians in Moca[1] and another 400 in Santiago[2] after an aborted attempt to expel the French forces led by Jean-Louis Ferrand. Ferrand would later be defeated by Juan Sánchez Ramírez in the Battle of Palo Hincado, after which he committed suicide with his own pistol.[8][2]

Events

editPrelude

editAfter the 1801 campaign by Toussaint Louverture into Santo Domingo which saw the emancipation of the enslaved population in the east, a large French force would land in Samaná Bay with the aid of the locals of Santo Domingo,[1] ending Louverture's unification with the eastern half of the island and using Santo Domingo as a springboard for a renewed French invasion of Haiti.[1][2] After gaining support from the Spaniard population for their rule on the island, the French forces under General François Marie Kerverseau and Jean-Luis Ferrand quickly moved to reinstate slavery, crushing the resistance of freedmen in the vicinity of the Nigua River.[2] The French forces sent on the Saint-Domingue expedition ultimately failed, resulting in the loss of almost all of the 50,000 strong invasion force sent to the island, although Louverture himself would be captured and die.[1][2] Seeking to consolidate the tenuous French position in the east, Ferrand executed a coup against the command of Kerverseau, combining their depleted forces and instituting a flurry of administrative changes. In an attempt to resuscitate Santo Domingo's collapsing economy which resulted from the continued emigration of white Spaniards, Ferrand gave a decree to expropriate the property of any person of the emigrant population who did not return by a given date,[2] as well as the reimportation of slaves to the island.[9] In 1804, boarder hostilities broke out, with the Haitians taking advantage of Ferrand's earlier evacuation of Santiago, La Vega and Cotuí to capture these towns, installing a mixed-race freedman of Santo Domingo named José Campos Tabares to lead them. French forces returned to expel the Haitians, but themselves abandoned the town due to fear of reprisal by Dessalines's forces. In May, Dessalines would address the following proclamation to the people of Santo Domingo:

To the inhabitants of the Spanish part. Scarce had the French army been expelled when you hastened to acknowledge my authority. By a free and spontaneous movement of your hearts, you ranged yourselves under my subjection. More careful of the prosperity than the ruin of that part which you inhabit, I gave to this homage a favorable reception. From that moment I considered you as my children and my fidelity to you remains undiminished. As a proof of my paternal forcitude, within the places which have submitted to my power, I have proposed for chiefs none but men chosen from among yourselves. Jealous of counting you in the ranks of my friends, that I might give you all the time necessary for recollection and I may assure myself of your fidelity. [...] The incensed Ferrand had not yet instilled into you the poison of falsehood and calumny. Writings originating in despair and weakness have been circulated, and immediately many amongst you, seduced by perfidious insinuations, solicited the friendship and protection of the French. They dare to outrage my kindness by coalescing with my cruel enemies. Spaniards, reflect! On the brink of the precipice which is dug under your feet, will that diabolical minister save you when with fire and sword I shall have pursued you to your last entrentchment? [...] To lure the Spaniards to their party, they propagate the report that vessels laden with troops have arrived at Santo Domingo. [...] To spread distrust and terror, they incessantly dwell upon the fate which the French have just experienced; but, have I not had reason to treat them so. The wrongs of the French, do they appertain to the Spaniards? And must I visit on the latter the crimes which the former have conceived, ordered, and executed upon our species? [...] A few moments more and I will crush the remnants of the French under the weight of my mighty power. Spaniards! You to whom I address solely because I wish to save you. You who, for having been guilty of evasion, shall speedily perserve your existence only so far as my clemency may deing to spare you. It is yet time, adjure an error which may be fatal to you and break off all connections with my enemy if you wish your blood may not be confounded with his. [...] Think of your preservation. Receive here the sacred promise which I make not do anything against your personal safety or your interests, if you seize upon this occasion to shew yourselves worthy of being admitted among the children of Haiti.

People would gradually return starting in July of that year, governed now by one José Serapio Reinoso del Orbe, to form military organizations to resist a future Haitian attack.[2] Ferrand would, in January 1805, declare the reinitiating of hostilities with Haiti and authorizing frontier forces and any of the denizens of Cibao and Ozama to raid Haiti for children to be enslaved on Dominican plantations and sold for export[2][1][11][9] (in part a measure meant to compensate the frontier forces for their defense), as well as ordering his comandante Joseph Ruiz to execute any Haitian male over the age of 14 found in Santo Domingo.[11] This would precipitate Dessalines's invasion in February of that year.[2]

Military campaign

editAfter crossing into Santo Domingo, a contingent of forces 2000 strong, led by Henri Christophe, had their march the capital opposed by the frontier forces of Santiago, despite their numbering only 200 men. The ensuing battle resulted in the total destruction of the smaller force, the men taken prisoner being beheaded and the town itself being sacked.[2] Those that fled to Moca were initially granted clemency on the condition that they no longer oppose the movement of Dessalines's army. Once the various forces met up on the outskirts of the capital, they found the city of 6000 had been fortified in anticipation of their attack, with all of the 2000 French soldiers on the island on the defense. They put the town to siege for three weeks, but upon seeing a local French fleet upon the horizon sail in the direction of Haiti, Dessalines broke off the assault, and rush to the defense of the country in the anticipation of a renewed French invasion.[2][6] Dessalines instead opted to raze various towns to deprive the French of militarily useful materiel.[6]

Massacre

editThese events were narrated in the accounts of witness Gaspar de Arredondo y Pichardo, a young law student living in Santiago, Santo Domingo, who would eventually come to live in Cuba.[5]

Dessalines, along with the army of Christophe, retreated to Haiti to brace for a renewed French invasion, and on the way, burned down towns on the retreat. According to Gaspar Arredondo y Pichardo, the town of Moca had its population massacred and the settlement itself burned.[5] As Price-Mars recounts his narrative, all persons encountered were killed, irrespective of their race.[7] As dictated by Pichardo:

The blacks entered the city like a fury of hell, cutting their throats sword in hand, trampling everything they found, and making blood run everywhere. Imagine what would be the consternation, terror and fright that that neighborhood, so neglected, fell silent for a moment, in view of similar events, when almost everyone was gathered in the main church, with their pastor imploring divine help, while it represented on the altar the sacrifice of our Redemption, and in readiness to receive communion, as one of the days of the year in which, by custom, even those in the country came to fulfill the annual precept. The throng of women fleeing without knowing where. The screams of children and the elderly who came out of their houses in terror. The ecclesiastical confused in the midst of those who asked him for comfort.

Speaking of the particulars of the events of Moca, and the massacre of the towns inhabitants in the church, Pichardo goes on to state:

A man who had not yet swallowed the sacramental species, was passed with a bayonet and was left lying at the door of the same sanctuary. From there, whoever was able to escape later fell into the hands of the caribes [Christophe's army] who roamed the city and did not spare any life they encountered.

[...]

All obeyed, believing that some pardon or grace was going to be proclaimed in their favor, but the pardon was to slaughter them all after the meeting like cornered sheep. The blacks after consummating the frightful, sacrilegious and barbarous sacrifice, left the town: that of all the women who were in the church, only two girls were left alive who were under the corpse of the mother, the aunt or the person who accompanied them, they pretended dead because they were covered with the blood that had spilled the corpse they had on top that in the presbytery. There were at least 40 children with their throats slit and on top of the altar a lady from Santiago, Mrs. Manuela Polanco, a woman from Don Francisco Campos, a member of the Departmental Council, who was sacrificed on the day of the invasion and hung on the arches of the Town Hall, with two or three mortal wounds from which he was dying.

The path of destruction by Dessalines's army on its return did not only carve through Moca, as explained in another excerpt of Pichardo, dictated by the survivor Eugenio Descamps, states that Dessalines's army burned each of the towns passed on the return journey, here saying:

There are in the Dominican south, the towns of San Jaun de la Maguana, Las Matas (de Farfán), Las Caobas; in the Dominican north (Cibao), the towns of Monte Plata, Cotuí, San Francisco de Macorís, Moca, La Vega, Santiago de los Caballeros and Monte Cristi. All ancient towns conserving in their traditions the horrors committed by those savage outlaws.

There are no colors to paint a picture of such terrible deeds.

Imagine a blind mass, possessed by the vertigo of crime, pushed as if by an insatiable wind to cross a people who, for tradition, for question of independence, for racial passion, were hated with they hatred of barbarians, with an implacable force. The career of the expeditionary army in its defeat is a sinister career that has as stages plundering, slaughter and burning. Plundered and burned are all the towns listed above. The most distinguished citizens and conspicuous families are vilely run over.

In Santiago de los Caballeros five priests were sent to the gallows. As the story goes, Dessalines himself set fire that illustrious city. Even before this, the ferocious invaders have adorned themselves with the songful bells of the beheadings of Moca, of which none speaks without horror.

The inhabitants of this industrious city ... with false promises they manage to return the population to the city. A suitable site for such a feast of human blood? Anywhere: the church suffices. There they make the innocent people go to give thanks for peace. Suddenly at a signal, the doors of the church are quickly closed, and that infamous soldiery commits [against them] unceasing evil! Ceasing neither before the innocent child who is bayoneted, nor before the venerable priest who officiates, and whose blood stains the pavement of the altar

The Otsego Herald newspaper, based in Cooperstown, New York, published details the Dessalines's 1805 campaign and reports on the Massacre at Santiago:

Haytian army had gone against Santo Domingo. They were said to amount to 40,000 men. Dessalines, the Emperor, had marched at the head of these until they reached Santiago, an inland town of considerable strength. A council of war was then held, when it was determined to storm the city. The Emperor, however, was requested not to risk his life in the attempt. The direction of the siege was given to General Brave, who, after a desperate and bloody conflict, succeeded in carrying the city; not, however, without considerable loss – It was rumored that General Brave was mortally wounded and had lost 1,000 of his best troops. The French and Spaniards found in the city, it was supposed, were all put to the sword. – Otsego Herald newspaper, April 25, 1805

On their retreat, prisoners from various city subject to destruction were rounded up by the army. In La Vegas and Santiago, Dominican men, women and children, a total of roughly 900 persons, were taken as captives. Forced to walk barefoot on their way to Haiti and prevented from wearing hats, they were treated brutally by their captors. They would be put to worked on Haitian state plantations system for a period of 4 years. [1]

Historicity

editAlthough the details of the massacre at Santiago and Moca are accepted by several historians, others have questioned the historicity of the events.[13] Renowned Dominican Historian and Priest, Fray Cipriano de Utrera, when addressing the matter, states that the event was "simply a criminal act carried out against several people, and not a general misery or misfortune of the population of Moca", further pointing out that priests writing histories which include 1805 never mention such beheadings.[14] Roberto Marte, another Dominican Historian of renown, argues that although the narrative of Pichardo offers some historical value, it cannot be accepted at face value.[4] He bases this on weaknesses and holes in the narrative, such the fact that this testimony was related nearly 40 years after the fact, claims to have observed events he was not present for, relies on hearsay which is not cited, and was constructed during Santo Domingo's war against Haiti.[4] Other historians have echoed Marte's critique of the text.[15]

Effect

editContemporary impacts

editPrior to the event, in response to the 1795 treaty of Basle which ceded all of Hispaniola to the French, large amounts of the white population began to emigrate off of the island and into nearby Spanish holdings, seeking to retain their status as Spanish subjects and possession of their property.[2][1] This flow rapidly accelerated after Louverture's unification of the island and formal abolition of slavery, with even more whites Spaniards departing from the island due to anxieties over being ruled by freedmen.[1] This would prove catastrophic to the economy, will almost all municipalities lacking laborers.[2] During the administration of Ferrand, the French general tried all possible methods to stem the emigration and entice back some portion of the departed whites. Whatever progress he had achieved to these ends was totally reversed by the 1805 invasion, with the path of destruction Dessalines carved on his return to Haiti and the abiding fear of future attacks this led to most of the remaining whites abandoning the colony in the years to come.[2][16] According to history writer Jan Rogoziński, the white emigration starting from 1801 would cause the population to drop nearly in half, from 125,000 in 1789 to 63,000 in 1819.[16] This would leave behind the largely mixed-race rural population to be the dominant demographic in Santo Domingo.[16] The efforts of Ferrand would eventually backfire, as upon Napoleon's 1808 invasion of Spain, local collaboration and support for his government would end, with the returned white population revolting — including Juan Sánchez Ramírez, who would defeat the general in battle, overthrow his government, and driving him to suicide.[8][2] The Haitians would assist the revolutionaries, who would go on to expel the last of the French forces from Santo Domingo.[1] This revolt would further devastate the country.[1]

Future impact

editThe nationalist sentiments prevailing among the Spaniard population of Santo Domingo would be vindicated, in their eyes, by the brutality of Dessalines's campaign.[17] In the aftermath of the event, and to a greater extent of the later conquest of the island which saw the upper classes lose much of their power, the white elite constructed a Dominican identity in opposition to Haiti: the people of Santo Domingo portrayed as White, Catholic, and culturally Hispanic — The Haitians being the opposite and inferior Black, Voodooist, who were culturally African.[17] In accordance with this, people in the colonial period of Santo Domingo would refer to themselves as blancos de la tierra (literally whites of the land) irrespective of race.[17]

Even after the Haitian aid to Dominican independence fighters in the Dominican Restoration War, Dominican elites would construct Antihaitianismo as a tool of Nationalism. The dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo would take this to new heights. Employing a team of Dominican intellectuals, he would reconstruct the history of the island into his nationalist narrative.[17] Peña Batlle would in an official address to the Dominican people state:

That type is frankly undesirable. Of pure African race, he cannot represent for us any ethnic incentive. Not well nourished and worse dressed, he is weak, though very prolific due to his low living conditions.

The memory of the Beheadings of Moca would be revived by the Trujillo regime, and be used to justify his policy of the extermination of Haitians from the Dominican Republic.[15]

In popular culture

editRecognized in The Feast of the Goat, a novel by Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Schoenrich, Otto (2013). Santo Domingo A Country with a Future. ISBN 978-3-8491-9198-6. OCLC 863932373.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Pons, Frank Moya (1991). "The Haitian Revolution in Santo Domingo (1789-1809)". Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas. 28 (1). Boehlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H. & Co. KG: 155. doi:10.7767/jbla.1991.28.1.125. ISSN 2194-3680.

- ^ Temboury, Francisco Javier (2016). El habla de Santo Domingo. Punto Rojo Libros S.L. p. 158. ISBN 978-8-416-97902-8.

- ^ a b c Marte, Roberto (2017). El pasado como historia (in Spanish). p. 208. ISBN 978-9945-9088-8-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Arredondo y Pichardo, Gaspar de (2008). Memoria de mi salida de la isla de Santo Domingo el 28 de abril de 1805.

- ^ a b c Sagás, E.; Inoa, O. (2003). The Dominican People: A Documentary History. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-55876-297-8. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- ^ a b Price-Mars, Jean (1953). La República de Haití y La República Dominicana (PDF).

- ^ a b Southley, Captain Thomas (1827). Chronological History of the West Indies. p. 421.

- ^ a b Matibag, E. (2003). Haitian-Dominican Counterpoint: Nation, State, and Race on Hispaniola. Palgrave Macmillan US. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4039-7380-1. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ Rainsford, M. (1805). An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti: Comprehending a View of the Principal Transactions in the Revolution of Saint Domingo; with Its Ancient and Modern State. Collections spéciales. J. Cundee. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- ^ a b Nessler, Graham (2012). ""THE SHAME OF THE NATION": THE FORCE OF RE-ENSLAVEMENT AND THE LAW OF "SLAVERY" UNDER THE REGIME OF JEAN-LOUIS FERRAND IN SANTO DOMINGO, 1804-1809". NWIG: New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 86 (1/2). [KITLV, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, Brill]: 5–28. ISSN 1382-2373. JSTOR 41850692. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ "Domestic Herald". Otsego Herald. 25 April 1805.

- ^ Marte, Roberto (2017). El pasado como historia (in Spanish). p. 50. ISBN 978-9945-9088-8-6.

- ^ Marte, Roberto (2017). El pasado como historia (in Spanish). p. 210. ISBN 978-9945-9088-8-6.

- ^ a b Giménez, Luis Alfonso Escolano (2022-03-05). ""Nación Esencial Versus Nación Histórica" y Discursiva Antihaitiana: Su Rol Central en la Formación de la Historiografía Nacionalista Dominicana hasta El Trujillismo". Criticæ. Revista Científica para el Fomento del Pensamiento Crítico. (in Spanish). 1 (01). ISSN 2794-0470. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ a b c Rogoziński, Jan (1999). A Brief History of the Caribbean. Facts On File. p. 221. ISBN 9780816038114.

- ^ a b c d e "Haiti: Antihaitianismo in Dominican Culture". faculty.webster.edu. 1943-09-20. Retrieved 2023-05-21.

- ^ "La agresión contra Lescot". 2007-07-30. Retrieved 6 October 2014.