Cat-scratch disease (CSD) is an infectious disease that most often results from a scratch or bite of a cat.[4] Symptoms typically include a non-painful bump or blister at the site of injury and painful and swollen lymph nodes.[2] People may feel tired, have a headache, or a fever.[2] Symptoms typically begin within 3–14 days following infection.[2]

| Cat scratch disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cat-scratch fever, felinosis, Teeny's disease, inoculation lymphoreticulosis, subacute regional lymphadenitis[1] |

| |

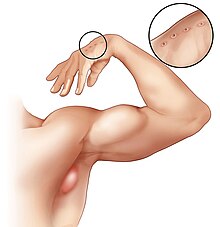

| An enlarged lymph node in the armpit region of a person with cat-scratch disease, and wounds from a cat scratch on the hand. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Bump at the site of the bite or scratch, swollen and painful lymph nodes[2] |

| Complications | Encephalopathy, parotitis, endocarditis, hepatitis[3] |

| Usual onset | Within 14 days after infection[2] |

| Causes | Bartonella henselae from a cat bite or scratch[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, blood tests[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Adenitis, brucellosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, lymphoma, sarcoidosis[3] |

| Treatment | Supportive treatment, azithromycin[2][3] |

| Prognosis | Generally good, recovery within 4 months[3] |

| Frequency | 1 in 10,000 people[3] |

Cat-scratch disease is caused by the bacterium Bartonella henselae which is believed to be spread by the cat's saliva.[2] Young cats pose a greater risk than older cats.[3] Occasionally dog scratches or bites may be involved.[3] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms.[3] Confirmation is possible by blood tests.[3]

The primary treatment is supportive.[3] Antibiotics speed healing and are recommended in those with severe disease or immune problems.[2][3] Recovery typically occurs within 4 months but can require a year.[3] About 1 in 10,000 people are affected.[3] It is more common in children.[4]

Signs and symptoms

editCat-scratch disease commonly presents as tender, swollen lymph nodes near the site of the inoculating bite or scratch or on the neck, and is usually limited to one side. This condition is referred to as regional lymphadenopathy and occurs 1–3 weeks after inoculation.[5] Lymphadenopathy most commonly occurs in the axilla,[6] arms, neck, or jaw, but may also occur near the groin or around the ear.[4] A vesicle or an erythematous papule may form at the site of initial infection.[4]

Most people also develop systemic symptoms such as malaise, decreased appetite, and aches.[4] Other associated complaints include headache, chills, muscular pains, joint pains, arthritis, backache, and abdominal pain. It may take 7 to 14 days, or as long as two months, for symptoms to appear. Most cases are benign and self-limiting, but lymphadenopathy may persist for several months after other symptoms disappear.[4] The disease usually resolves spontaneously, with or without treatment, in one month.

In rare situations, CSD can lead to the development of serious neurologic or cardiac sequelae such as meningoencephalitis, encephalopathy, seizures, or endocarditis.[4] Endocarditis associated with Bartonella infection has a particularly high mortality.[5] Parinaud's oculoglandular syndrome is the most common ocular manifestation of CSD,[4] and is a granulomatous conjunctivitis with concurrent swelling of the lymph node near the ear.[7] Optic neuritis or neuroretinitis is one of the atypical presentations.[8]

People who are immunocompromised are susceptible to other conditions associated with B. henselae and B. quintana, such as bacillary angiomatosis or bacillary peliosis.[4] Bacillary angiomatosis is primarily a vascular skin lesion that may extend to bone or be present in other areas of the body. In the typical scenario, the patient has HIV or another cause of severe immune dysfunction. Bacillary peliosis is caused by B. henselae that most often affects people with HIV and other conditions causing severe immune compromise. The liver and spleen are primarily affected, with findings of blood-filled cystic spaces on pathology.[9]

Cause

editBartonella henselae is a fastidious,[5] intracellular, Gram-negative bacterium.

Transmission

editThe cat was recognized as the natural reservoir of the disease in 1950 by Robert Debré.[5] Kittens are more likely to carry the bacteria in their blood, so may be more likely to transmit the disease than adult cats.[10] However, fleas serve as a vector for transmission of B. henselae among cats,[5] and viable B. henselae are excreted in the feces of Ctenocephalides felis, the cat flea.[11] Cats could be infected with B. henselae through intradermal inoculation using flea feces containing B. henselae.[12]

As a consequence, a likely means of transmission of B. henselae from cats to humans may be inoculation with flea feces containing B. henselae through a contaminated cat scratch wound or by cat saliva transmitted in a bite.[5] Ticks can also act as vectors and occasionally transmit the bacteria to humans.[4] Combined clinical and PCR-based research has shown that other organisms can transmit Bartonella, including spiders.[13][14] Cryptic Bartonella infection may be a much larger problem than previously thought, constituting an unrecognized occupational health hazard of veterinarians.[15]

Diagnosis

editThe best diagnostic method available is polymerase chain reaction, which has a sensitivity of 43-76% and a specificity (in one study) of 100%.[5] The Warthin–Starry stain can be helpful to show the presence of B. henselae, but is often difficult to interpret. B. henselae is difficult to culture and can take 2–6 weeks to incubate.[5]

Histology

editCat-scratch disease is characterized by granulomatous inflammation on histological examination of the lymph nodes. Under the microscope, the skin lesion demonstrates a circumscribed focus of necrosis, surrounded by histiocytes, often accompanied by multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. The regional lymph nodes demonstrate follicular hyperplasia with central stellate necrosis with neutrophils, surrounded by palisading histiocytes (suppurative granulomas) and sinuses packed with monocytoid B cells, usually without perifollicular and intrafollicular epithelioid cells. This pattern, although typical, is only present in a minority of cases.[16]

Prevention

editCat-scratch disease can be primarily prevented by taking effective flea control measures; since cats are mostly exposed to fleas when they are outside, keeping cats inside can help prevent infestation. Strictly-indoor cats without exposure to indoor-outdoor animals are generally at negligible risk of infestation.[17] Cats which are carrying the bacterium, B. henselae, are asymptomatic,[18] thus thoroughly washing hands after handling a cat or cat feces is an important factor in preventing potential cat-scratch disease transmission from possibly infected cats to humans.[17]

Treatment

editMost healthy people clear the infection without treatment, but in 5 to 14% of individuals, the organisms disseminate and infect the liver, spleen, eye, or central nervous system.[19] Although some experts recommend not treating typical CSD in immunocompetent people with mild to moderate illness, treatment of all people with antimicrobial agents (Grade 2B) is suggested due to the probability of disseminated disease. The preferred antibiotic for treatment is azithromycin, since this agent is the only one studied in a randomized controlled study.[20]

Azithromycin is preferentially used in pregnancy to avoid the teratogenic side effects of doxycycline.[21] However, doxycycline is preferred to treat B. henselae infections with optic neuritis due to its ability to adequately penetrate the tissues of the eye and central nervous system.[5]

Epidemiology

editCat-scratch disease has a worldwide distribution, but it is a nonreportable disease in humans, so public health data on this disease are inadequate.[22] Geographical location, present season, and variables associated with cats (such as exposure and degree of flea infestation) all play a factor in the prevalence of CSD within a population.[23] In warmer climates, the CSD is more prevalent during the fall and winter,[23] which may be attributed to the breeding season for adult cats, which allows for the birth of kittens.[23] B henselae, the bacterium responsible for causing CSD, is more prevalent in younger cats (less than one year old) than it is in adult cats.[22]

To determine recent incidence of CSD in the United States, the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database was analyzed in a case control study from 2005 to 2013.[24] The database consisted of healthcare insurance claims for employees, their spouses, and their dependents. All participants were under 65 years of age, from all 50 states. The length of the study period was 9 years and was based on 280,522,578 person-years; factors such as year, length of insurance coverage, region, age, and sex were used to calculate the person-years incidence rate to eliminate confounding variables among the entire study population.[24]

A total of 13,273 subjects were diagnosed with CSD, and both in- and outpatient cases were analyzed. The study revealed an incidence rate of 4.5/100,000 outpatient cases of cat-scratch disease. For inpatient cases, the incidence rate was much lower at 0.19/100,000 population.[24] Incidence of CSD was highest in 2005 among outpatient cases and then slowly declined. The Southern states had the most significant decrease of incidence over time. Mountain regions have the lowest incidence of this disease because fleas are not commonly found in these areas.[24]

Distribution of CSD among children aged 5–9 was of the highest incidence in the analyzed database, followed by women aged 60–64. Incidence among females was higher than that among males in all age groups.[24] According to data on social trends, women are more likely to own a cat over men;[25] which supports higher incidence rates of this disease in women. Risk of contracting CSD increases as the number of cats residing in the home increases.[22] The number of pet cats in the United States is estimated to be 57 million.[23] Due to the large population of cats residing in the United States, the ability of this disease to continue to infect humans is vast. Laboratory diagnosis of CSD has improved in recent years, which may support an increase in incidence of the disease in future populations.[23]

Outbreaks

editHistorically, the number of reported cases of CSD has been low, there has been a significant increase in reports in urban and suburban areas in the northeast region of United States. An example of the increased incidence can be found in Essex County, New Jersey. In 2016, there were 6 reported cases. In 2017, there were 51 reported cases. In 2018, there were 263 reported cases. Although usually treated with antibiotics and minimal long-term effects, there have been 3 reported case of tachycardia more than one year after exposure.[26]

History

editSymptoms similar to CSD were first described by Henri Parinaud in 1889, and the clinical syndrome was first described in 1950 by Robert Debré.[27][5] In 1983, the Warthin-Starry silver stain was used to discover a Gram-negative bacillus which was named Afipia felis in 1991 after it was successfully cultured and isolated. The causative organism of CSD was originally believed to be Afipia felis, but this was disproved by immunological studies in the 1990s demonstrating that people with cat-scratch fever developed antibodies to two other organisms, B. henselae (originally known as Rochalimea henselae before the genera Bartonella and Rochalimea were combined) and B. clarridgeiae, which is a rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium.[5]

References

edit- ^ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Cat scratch disease". GARD. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Bartonellosis". NORD. 2017. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Klotz SA, Ianas V, Elliott SP (2011). "Cat-scratch Disease". American Family Physician. 83 (2): 152–5. PMID 21243990.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Florin TA, Zaoutis TE, Zaoutis LB (2008). "Beyond cat scratch disease: widening spectrum of Bartonella henselae infection". Pediatrics. 121 (5): e1413–25. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1897. PMID 18443019. S2CID 14094482.

- ^ Jürgen Ridder R, Christof Boedeker C, Technau-Ihling K, Grunow R, Sander A. Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 35, Issue 6, 15 September 2002, Pages 643–649, https://doi.org/10.1086/342058

- ^ Catscratch Disease~clinical at eMedicine

- ^ Gajula V, Kamepalli R, Kalavakunta JK (2014). "A star in the eye: cat scratch neuroretinitis". Clinical Case Reports. 2 (1): 17. doi:10.1002/ccr3.43. PMC 4184768. PMID 25356231.

- ^ Perkocha LA, Geaghan SM, Yen TS, Nishimura SL, Chan SP, Garcia-Kennedy R, Honda G, Stoloff AC, Klein HZ, Goldman RL (1990). "Clinical and pathological features of bacillary peliosis hepatis in association with human immunodeficiency virus infection". The New England Journal of Medicine. 323 (23): 1581–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM199012063232302. PMID 2233946.

- ^ "Cat Scratch Disease | Healthy Pets, Healthy People | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2021-09-17. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ Higgins JA, Radulovic S, Jaworski DC, Azad AF (1996). "Acquisition of the cat scratch disease agent Bartonella henselae by cat fleas (Siphonaptera:Pulicidae)". Journal of Medical Entomology. 33 (3): 490–5. doi:10.1093/jmedent/33.3.490. PMID 8667399.

- ^ Foil L, Andress E, Freeland RL, Roy AF, Rutledge R, Triche PC, O'Reilly KL (1998). "Experimental infection of domestic cats with Bartonella henselae by inoculation of Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) feces". Journal of Medical Entomology. 35 (5): 625–8. doi:10.1093/jmedent/35.5.625. PMID 9775583.

- ^ Copeland, Claudia S. (2015). "Cat Scratch Fever? Really?: Cats, Fleas and the Many Faces of Bartonellosis". Healthcare Journal of Baton Rouge: 28–34. Archived from the original on 2015-11-22.

- ^ Mascarelli PE, Maggi RG, Hopkins S, Mozayeni BR, Trull CL, Bradley JM, Hegarty BC, Breitschwerdt EB (2013). "Bartonella henselae infection in a family experiencing neurological and neurocognitive abnormalities after woodlouse hunter spider bites". Parasites & Vectors. 6: 98. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-6-98. PMC 3639822. PMID 23587343.

- ^ Lantos PM, Maggi RG, Ferguson B, Varkey J, Park LP, Breitschwerdt EB, Woods CW (2014). "Detection of Bartonella species in the blood of veterinarians and veterinary technicians: a newly recognized occupational hazard?". Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 14 (8): 563–70. doi:10.1089/vbz.2013.1512. PMC 4117269. PMID 25072986.

- ^ Rosado FG, Stratton CW, Mosse CA (2011). "Clinicopathologic correlation of epidemiologic and histopathologic features of pediatric bacterial lymphadenitis". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 135 (11): 1490–3. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0581-OA. PMID 22032579.

- ^ a b Nelson, Christina A.; Saha, Shubhayu; Mead, Paul S. (2016). "Cat-Scratch Disease in the United States, 2005–2013". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (10): 1741–1746. doi:10.3201/eid2210.160115. PMC 5038427. PMID 27648778.

- ^ "Cat Scratch Disease". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Carithers, H. A. (1985-11-01). "Cat-scratch disease. An overview based on a study of 1,200 patients". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 139 (11): 1124–1133. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1985.02140130062031. ISSN 0002-922X. PMID 4061408.

- ^ Rolain, J. M.; Brouqui, P.; Koehler, J. E.; Maguina, C.; Dolan, M. J.; Raoult, D. (2004-06-01). "Recommendations for Treatment of Human Infections Caused by Bartonella Species". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 48 (6): 1921–1933. doi:10.1128/AAC.48.6.1921-1933.2004. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 415619. PMID 15155180.

- ^ Catscratch Disease~treatment at eMedicine

- ^ a b c Chomel, Bruno B.; Boulouis, Henri J.; Breitschwerdt, Edward B. (April 15, 2004). "Cat scratch disease and other zoonotic Bartonella infections" (PDF). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 224 (8): 1270–1279. doi:10.2460/javma.2004.224.1270. PMID 15112775. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Windsor, Jeffrey J. (2001). "Cat-scratch Disease: Epidemiology, Etiology, and Treatment". British Journal of Biomedical Science. 58 (2): 101–110. PMID 11440202. S2CID 13122848.

- ^ a b c d e Nelson, Christina A.; Saha, Shubhayu; Mead, Paul S. (2016). "Cat-Scratch Disease in the United States, 2005–2013". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (10): 1741–1746. doi:10.3201/eid2210.160115. PMC 5038427. PMID 27648778.

- ^ "Profile of Pet Owners". Pew Research Center. November 4, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ "Cat-Scratch Disease". Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Asano S (2012). "Granulomatous lymphadenitis". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hematopathology. 52 (1): 1–16. doi:10.3960/jslrt.52.1. PMID 22706525.

External links

edit- Cat Scratch Disease on National Organization for Rare Disorders site