Berenice Troglodytica, also called Berenike (Greek: Βερενίκη) or Baranis, is an ancient seaport of Egypt on the western shore of the Red Sea. It is situated about 825 km south of Suez, 260 km east of Aswan in Upper Egypt and 140 km south of Marsa Alam.[2] It was founded in 275 BCE by Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BCE), who named it after his mother, Berenice I of Egypt.[3]

Βερενίκη | |

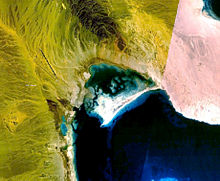

Satellite image of Berenice Troglodytica, on the Red Sea coast | |

| Alternative name | Berenice Troglodytica, Baranis, Berenike[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | Red Sea Governorate, Egypt |

| Region | Upper Egypt |

| Coordinates | 23°54′31″N 35°28′21″E / 23.90861°N 35.47250°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Ptolemy II |

| Founded | First half of the 3rd century BCE |

| Abandoned | After the 6th century CE |

| Periods | Ptolemaic Kingdom to Byzantine Empire |

A high mountain range runs along the African coast and separates the Nile Valley from the Red Sea; Berenice was sited upon a narrow rim of shore between the mountains and the Red Sea, at the head of the Sinus Immundus,[4] a south-facing bay sheltered on the north by a high peninsula then called Lepte Extrema, and to the south by a chain of small islands scattered across the mouth of the bay. One of them was called the Island of Ophiodes (Ὀφιώδης νήσος[4][5]) and was one of a few sources of gemstones local to Berenice. The harbour is marginal, but was improved by engineering.

Etymology

editThe name Troglodytica refers to the native people of the region, the "Troglodytai" or "cave dwellers". Although the name is attested by several ancient writers, the more ancient Ptolemaic inscriptions read Trogodytai, which Huntingford (1980)[6] speculated could be derived from the same root as Tuareg. It is possible that later copyists confused this name with the more common term Troglodytai.[6]

History

editPtolemaic era

edit

| ||||||

| šꜣs ḥrt[7][8] in hieroglyphs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC) | ||||||

Berenice was prosperous and quite famous in antiquity. The city is noted by most ancient geographers, including Strabo,[9] Pliny the Elder,[10] and Stephanus of Byzantium.[11] Its prosperity after the third century was mostly due to three reasons:

- patronage by the Ptolemaic kings

- safe anchorage

- being at the eastern terminus of the main road from Upper Egypt.

The other terminus of that road is Coptos (now Qift), an Egyptian city on the Nile, which made Berenice and Myos Hormos the two main shipping centers for trade between Aethiopia and Egypt on the one hand, and Syria, Tamilakkam, and Tamraparni (ancient Sri Lanka) on the other.[12] The road across the desert from Coptos was 258 Roman miles long, or 11 days' journey. Watering stations (Greek hydreumata, see Hadhramaut) were built along the road; the wells and resting places for caravans are listed by Pliny,[13] and in the Itineraries.[14]

In the 19th century Belzoni[15] found traces of several of the watering stations.

Berenice was able to generate some commerce locally: The mines of Gebel Zabara and Wadi Sikait in the adjacent mountains, and the island of Ophiodes (now Zabargad Island) in the mouth of Berenice's harbor, were rich sources of gemstones (peridot?) at that time called “topaz” and “emerald”.[16]

Imperial Roman era

editFrom the 1st century BCE until the 2nd century CE, Berenice was one of the critical way-stations for trade between the Indian subcontinent, Arabia, and Upper Egypt. It was connected to Antinoöpolis on the River Nile in Lower Egypt by the Via Hadriana in 137 CE.

The trade from Berenice along the Red Sea coast is described in the 1st century CE travelogue Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written by a Greek merchant based in Alexandria. The Periplus states that "on the right-hand coast next below Berenice is the country of the Berbers", thereby placing Berenice Troglodytica just north of ancient Barbara.[17]

In the 4th century Berenice had again become an active port. Under the Roman administration, Berenice itself formed an entire district with its own prefect, who was called Praefectus Berenicidis, or P. montis Berenicidis.[18]

Despite its favorable location, after the 6th century the port was abandoned and the bay has since nearly filled with sediment; it has a sand-bar at its entrance that can only be crossed by shallow-draft boats.[19] The gemsites on Zabargad Island are flooded.[20]

19th century archaeology

editIn 1818, the ruins of Berenice were identified by Giovanni Battista Belzoni, confirming an earlier opinion of d'Anville. Belzoni wrote that the city measured 1,600 feet (490 m) from north to south, and 2,000 feet (610 m) from east to west. He estimated the ancient population at 10,000.[21] Since then, several excavations have been undertaken.[19]

The most important ruin is a temple; the remnants of its sculptures and inscriptions preserve the name of Tiberius and the head magistrate of the Jews in Alexandria under Ptolemaic and Roman rule. Excavations have also produced small figures of many deities, some obscure, including a (goddess?) Alabarch or Arabarch.

The temple is Egyptian style, made of sandstone and a soft calcareous stone. It is 102 feet (31 m) long, and 43 feet (13 m) wide. A portion of its walls are sculptured with well-executed basso relieves, of Greek workmanship; occasionally the walls are decorated with hieroglyphics.

Recent archaeology

editExcavations were launched at Berenike in 1994 by a team of archaeologists from the University of Delaware led by Prof. Steven E. Sidebotham, with partners from several other institutions and continued until 2001. Work was resumed by teams from the University of Delaware and the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland, in the winter of 2007–2008 and is still continuing. Apart from the excavations, non-invasive magnetic prospecting was carried out. Tomasz Herbich from the Institute of Archeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences made a magnetic map of the western part of the site.[2]

A large number of significant finds have been made providing evidence of the cargo from the Malabar Coast and the presence of Tamil people from South India being at this last outpost of the Roman Empire (see ancient Indo-Roman trade relations).

- "Among the unexpected discoveries at Berenike were a range of ancient Indian goods, including the largest single concentration (7.55 kg) of black peppercorns ever recovered in the classical Mediterranean world (“imported from Southern India” and found inside a large vessel made of Nile silt in a temple courtyard); substantial quantities of Indian-made fine ware and kitchen cooking ware and Indian style pottery; Indian-made sail cloth, basketry, matting, etc. from trash dumps; a large quantity of teak wood, black pepper, coconuts, beads made of precious and semi-precious stones, cameo blanks; “a Tamil Brahmi graffito mentioning Korra, a South Indian chieftain”; evidence that “inhabitants from Tamil South India (which then included most of Kerala) were living in Berenike, at least in the early Roman period”; evidence that the Tamil population implied the probable presence of Buddhist worshippers; evidence of Indians at another Roman port 300 km north of Berenike; Indian-made ceramics on the Nile road; a rock inscription mentioning an Indian passing through en route; “abundant evidence for the use of ships built and rigged in India”; and proof “that teak wood (endemic to South India), found in buildings in Berenike, had clearly been reused” (from dismantled ships)."[22]

In 2009 the first find of frankincense was reported and "two blocks of resin from the Syrian fir tree (Abies cilicica), one weighting about 190 g and the other about 339 g, recovered from 1st century CE contexts in one of the harbor trenches. Produced in areas of greater Syria and Asia Minor, this resin and its oil derivative were used in mummification, as an antiseptic, a diuretic, to treat wrinkles, extract worms and promote hair growth."[2]

“Extensive and intensive research initiated by Iwona Zych in the area of the southern harbor bay has uncovered workshop buildings, remains of ship boards, ropes, mooring lines, as well as a so-called harbor temenos with two structures probably of sacral character – the Lotus Temple and the Square Feature. Berenike in the early Roman period was a vibrant town in the desert where the greatest fortunes of the time were made. The archaeological excavations have uncovered remains of luxury goods, precious glass, bronze figurines, ostraca, papyri.”[2]

The expedition also discovered a cemetery of small animals dated c. 1st–2nd century CE, which has been excavated by Marta and Piotr Osypiński from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences since 2011.[23][24]

In 2019, a 2,300 year-old fortress was discovered by a team of archaeologists from the University of Warsaw and the Polish Academy of Sciences. The structure, built near the southern frontier, had thicker walls to the west, and served as a hub to transport war elephants from Eritrea.[25] In the same year was excavated an Isis temple and there, there were found fragments of a statue of the Meroitic god Sebiumeker.[26]

In 2020–2021, 2,000 year-old remains of monkeys, cats, and dogs were discovered at Berenike to be considered the oldest pet cemetery in the world.[27][24]

In Berenike in March 2022 an American-Polish archaeological mission excavating the main early Roman period temple dedicated to the Goddess Isis uncovered in the forecourt of the temple a marble statue of a Buddha, the Berenike Buddha.[28][29]

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Final Report for 5th season - Pattanam Excavation (PDF) (Report). Tiruvananthapuram, India: Kerala Council for Historical Research. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Berenike". pcma.uw.edu.pl. 2019-04-17. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ^ Michael Peppard (2009). "A letter concerning boats in Berenike and trade on the Red Sea." Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bd. 171, p. 196.

- ^ a b Strabo xvi. p. 770;[full citation needed]

- ^ Diod. iii. 39[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Huntingford, G.W.B. (1980). "The ethnology and history of the area covered by the Periplus". Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. London, UK.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[full citation needed] - ^ Gauthier, Henri (1928). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques. Vol. 5. p. 107.

- ^ Wallis Budge, E.A. (1920). An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary. Vol. II. John Murray. p. 1038.

With an index of English words, king list and geological list with indexes, list of hieroglyphic characters, coptic and semitic alphabets, etc.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, xvi.770, xvii.815.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, vi.(26).103, vi.(33).168.

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. [full citation needed]

- ^ Sidebotham, Steven E. (2019). Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route. Univ. of California Press. pp. 237–238. ISBN 9780520303386. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Pliny the Elder vi. 23. s. 26 [full citation needed]

- ^ Antonine Itinerary p. 172, f. [full citation needed]

- ^ Giovanni Battista Belzoni, Travels, vol. ii. p. 35 [full citation needed]

- ^ Smith, William (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography: Abacaenum-Hytanis. London, UK: Walton and Maberly. pp. 391–392.

- ^ Schoff, Wilfred Harvey (1912). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and trade in the Indian ocean by a merchant of the first century. London, Bombay & Calcutta. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Orelli, Inscr. Lat. no. 3880, f.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 769–770.

- ^ See article Luminous gemstones § Island of Ophiodes.

- ^ Giovanni Battista Belzoni, Researches, vol. ii. p. 73.[full citation needed]

- ^ "South Indians in Roman Egypt?". www.frontline.in. 2010-04-23. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- ^ Osypińska, M.; Osypiński, P. (2017). "New evidence for the emergence of a human–pet relation in early Roman Berenike (1st–2nd centuries AD)". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 26 (2): 167–192. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0012.1825. S2CID 189400184.

- ^ a b Grimm, David (2021-02-26). "Graves of nearly 600 cats and dogs in ancient Egypt may be world's oldest pet cemetery". Science Magazine. Archaeology, Plants, & Animals. American Association for the Advancement of Science. doi:10.1126/science.abh2835. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

Archaeozoologist Marta Osypinska and her colleagues at the Polish Academy of Sciences discovered the graveyard just outside the city walls [of Berenice], beneath a Roman trash dump, in 2011. The cemetery appears to have been used between the first and second centuries CE, when Berenice was a bustling Roman port that traded ivory, fabrics, and other luxury goods from India, Arabia, and Europe.

- ^ Jarus, Owen (3 January 2019). "This 2,300 year-old Egyptian fortress had an unusual task: Guarding a port that sent elephants to war". Live Science. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- ^ Geisburch, Jan (Autumn 2019). "Digging Diary 2019". Egyptian Archaeology. Vol. 55. S. 27.

- ^ "Monkeys found buried in 2,000 year-old Egyptian pet cemetery". Smithsonian Magazine. 27 August 2020.

- ^ "Garum Masala;Dramatic archaeological discoveries have led scholars to radically reassess the size and importance of the trade between ancient Rome and India". New York Review. 20 April 2023.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Parker, Christopher. "Archaeologists Unearth Buddha Statue in Ancient Egyptian Port City". Smithsonian Magazine.

References

edit- I. Zych, J. K. Rądkowska (2019). "Exotic cults in Roman Berenike? An investigation into two temples in the harbour temenos". [In] A. Manzo, C. Zazzaro, & D. Joyce de Falco (eds), Stories of Globalisation: The Red Sea and the Persian Gulf from late prehistory to early modernity, Selected Papers of Red Sea Project VII, Brill nv, Leiden, NL. pp. 225–245

- J. Then-Obłuska (2018). "Beads and pendants from the Hellenistic to early Byzantine Red Sea port of Berenike, Egypt. Season 2014 and 2015." Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 27 (1), pp. 203–234

- M. Woźniak (2017). "Shaping a city and its defenses: fortifications of Hellenistic Berenike Trogodytika." Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 26 (2), pp. 43–60.

- I. Zych (2017). "The harbor of early Roman “Imperial” Berenike: overview of excavations from 2009 to 2015." Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 26 (2), pp. 93–132.

- M. Osypińska & P. Osypiński (2017). "New evidence for the emergence of a human–pet relation in early Roman Berenike (1st–2nd century AD)". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 26 (2), pp. 167–192.

- S. E. Sidebotham, I. Zych, J. K. Rądkowska, & M. Woźniak (2015). "The Berenike Project: Hellenistic fort, Roman harbor and late Roman temple. Archaeological fieldwork and studies in the 2012 and 2013 seasons". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 24 (1), pp. 297–322.

- David Meredith (Dec 1957). "Berenice Troglodytica". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 43, pp. 56–70

- Huntingford, G.W.B. (1980). "The ethnology and history of the area covered by the Periplus". Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. London, UK.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - S. Sidebotham and W. Wendrich, (2001). "Roms Tor am Roten Meer nach Arabien und Indien". AW 32 (3), p. 251-263.[full citation needed]

- Berenike Project run by Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw

External links

edit- Fordham.edu: Periplus of the Erythraean Sea — Schoff translation.

- The Berenike Project