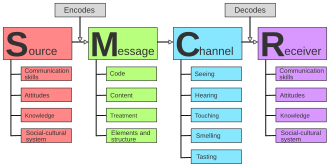

The source–message–channel–receiver model is a linear transmission model of communication. It is also referred to as the sender–message–channel–receiver model, the SMCR model, and Berlo's model. It was first published by David Berlo in his 1960 book The Process of Communication. It contains a detailed discussion of the four main components of communication: source, message, channel, and receiver. Source and receiver are usually distinct persons but can also be groups and, in some cases, the same entity acts both as source and receiver. Berlo discusses both verbal and non-verbal communication and sees all forms of communication as attempts by the source to influence the behavior of the receiver. The source tries to achieve this by formulating a communicative intention and encoding it in the form of a message. The message is sent to the receiver using a channel and has to be decoded so they can understand it and react to it. The efficiency or fidelity of communication is defined by the degree to which the reaction of the receiver matches the purpose motivating the source.

Each of the four main components has several key attributes. Source and receiver share the same four attributes: communication skills, attitudes, knowledge, and social-cultural system. Communication skills determine how good the communicators are at encoding and decoding messages. Attitudes affect whether they like or dislike the topic and each other. Knowledge includes how well they understand the topic. The social-cultural system encompasses their social and cultural background.

The attributes of the message are code, content, and treatment as well as elements and structure. A code is a sign system like a language. The content is the information expressed in the message. The treatment consists of the source's choices on the level of code and content when formulating the message. Each of these attributes can be analyzed based on the elements it uses and based on how they are combined to form a structure.

The remaining main component is the channel. It is the medium and process of how the message is transmitted. Berlo discusses it primarily in terms of the five senses used to decode messages: seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting. Depending on the message, some channels are more useful than others. It is often advantageous to use several channels simultaneously.

The SMCR model has been applied to various fields, such as mass communication, communication at the workplace, and psychology. It also influenced many subsequent communication theorists. It has been criticized for oversimplifying communication. For example, as a linear transmission model, it does not include the discussion of feedback loops found in many later models. Another common objection is that the SMCR model fails to take noise and other barriers to communication seriously and simply assumes that communication attempts are successful.

Background

editDavid Berlo published his source–message–channel–receiver (SMCR) model of communication in his 1960 book The Process of Communication.[2] Some theorists also refer to it as the sender–message–channel–receiver model.[3] Its exact formulation is usually attributed to Berlo[4] but models with similar components were already proposed earlier, such as the Shannon–Weaver model and Schramm's model. For this reason, term SMCR model is sometimes used to refer to these models as well.[5]

Nature and purpose of communication

editAccording to Berlo, communication is based on things that source and receiver have in common.[4] He understands communication in a very wide sense that includes non-verbal communication like body language or the use of color in advertisements besides verbal communication in spoken or written form. In the widest sense, "anything to which people attach meanings may be and is used in communication".[6][7] Berlo sees communication as a dynamic process that does not consist of a fixed sequence of events with a clearly defined beginning, middle, or end. But he acknowledges that the structure of language makes it necessary to describe communication in such a linear way.[8]

Berlo holds that the goal of all forms of communication is to influence the behavior of the audience.[9][10] In this regard, he rejects the idea that other goals, like informing the receiver or entertaining them, are equally important. He argues that these distinctions are not exclusive. This means that even attempts to inform, as in the case of regular education, or to entertain, as in the case of entertainment programs on television, are attempts to influence the behavior of the audience. Berlo gives a biological argument for this position by holding that "[our] basic purpose is to alter the relationship between our own organism and the environment".[11][9][12]

For Berlo, communication is just one way to achieve this in relation to other people that are part of the environment: "we communicate to influence".[13] For this reason, understanding communication involves understanding the source's goal, i.e. what reaction they intend to provoke in the audience. However, the source may not always be conscious of their reasons for communicating. For example, a writer may believe their purpose is to write a technical report rather than to influence the behavior of the reader. Likewise, a teacher may think their purpose is to cover the syllabus rather than to affect the behavior of the students. This is similar to how the purpose of many ingrained habits, communicational and otherwise, is to affect the environment even though the agent is often not aware of it while performing them. Berlo acknowledges such cases and understands them as forms of misperception or inefficiency.[14][8]

Usually, the source has a specific person in mind whom they wish to affect. Intrapersonal communication is a special case: the source and the receiver is the same person.[15] In such cases, the source tries to influence itself, like a poet who writes poetry in secret in order to emotionally affect themselves. However, the more common goal is to influence others. The intended effect can be immediate or delayed. An artist trying to entertain their audience intends an immediate effect while an employer giving instructions for the rest of the week intends to have a delayed effect on the employees' behavior. Messages can also produce unintended outcomes, such as when the intended receiver does not react as the source anticipated or when the message reaches unintended receivers.[16][9]

Relation to earlier models

editBerlo's model was influenced by earlier models like the Shannon–Weaver model and Schramm's model.[17][18][19] Other influences include models developed by Theodore Newcomb, Bruce Westley, and Malcolm MacLean Jr.[20][4][17] The Shannon–Weaver model was published in 1948 and is one of the earliest and most influential models of communication. It explains communication in terms of five basic components: a source, a transmitter, a channel, a receiver, and a destination. The source produces the message. To send the message, it has to be translated into a signal by the transmitter. To transmit this signal, a channel is required. At this stage, noise may interfere with the signal and distort it. Once the signal reaches the receiver, it is translated back into a message and made available to the destination. When making a landline phone call, the person calling is the source and their telephone is the transmitter. The wire is the channel and the person receiving the phone call is the destination. Their telephone is the receiver.[21][22][23] Berlo made slight adjustments to many of the basic components of the Shannon–Weaver model to include them in his own model.[17]

Schramm's model of communication is another significant influence on Berlo's model. It was first published by Wilbur Schramm in 1954. For Schramm, communication starts with an idea in the mind of the source. This idea is then encoded into a message and sent to the receiver. The receiver then has to decode and interpret the message to reproduce the original idea.[24][25][26] The concept of fields of experience plays a central role in this regard and was influential for Berlo. The field of experience of a person is their mental frame of reference and includes past life experiences as well as attitudes, values, and beliefs. Communication is only possible if the message is located within both fields of experience. If the message is outside the receiver's field of experience then they cannot reconstruct the sender's idea. This can happen when there are big cultural differences.[25][27][28] Similar ideas are expressed in the SMCR model in the discussion of how attitudes, knowledge, and the social-cultural system of the participants shape communication.[29]

Overview and basic components

editThe SMCR model is usually described as a linear transmission model of communication.[4][17] Its main focus is to identify the basic parts of communication and to show how their characteristics shape the communicative process. In this regard, Berlo understands his model as "a model of the ingredients of communication".[24] He identifies four basic components: source, message, channel, and receiver.[4][1] The source is the party that wants to communicate an idea. They have to encode this idea in the form of a message. The message contains the information to be transmitted. The channel is the means used to send the message. The receiver is the audience for whom the message is intended. They have to decode it to understand it.[4][30]

Despite the emphasis on only four basic components, Berlo initially identifies a total of six components. The two additional components are encoder and decoder.[31] The encoder is responsible for translating the idea into a message and the decoder is responsible for translating the message back into an idea.[32] Berlo holds that these six components are necessary to account for communication in its most general sense. However, the model can be simplified to four components for regular person-to-person communication. This is the case because source and encoder can be grouped together as one entity, just like decoder and receiver. In this regard, Berlo speaks of the source-encoder and the decoder-receiver. Treating the additional components separately is especially relevant for technical forms of communication. For example, in the case of a telephone conversation, the message is transmitted as an electrical signal and the telephone devices act as encoder and decoder.[31][33][34]

Each of the four main components is characterized by parts that influence the communicative process.[8] Berlo's main interest in discussing them is to study the conditions of the fidelity of communication. For Berlo, every communication is motivated by a goal the source intends to achieve and fidelity means that the source gets what they want. Fidelity is also called effectiveness and is the opposite of noise.[30]

Source and receiver

editSource and receiver are usually individual persons, such as an employee reporting their progress to the employer. But groups of people can also take these roles, as when two nations enter into trade negotiations.[8] Communication usually happens between distinct entities. Intrapersonal communication is an exception where the same person acts as source and receiver.[15] Berlo discusses several aspects of sender and receiver that affect communication. He organizes them into four categories: communication skills, attitudes, knowledge, and social-cultural system.[35] Some theorists identify five features by talking about the social system and the culture as two separate aspects.[17][19][1] The same characteristics apply to both source and receiver but play different roles for them.[8] How the communication takes place and what meaning is attached to the message depends on these factors.[17][19][1] Generally speaking, the more the factors of source and receiver match each other, the more likely it is that communication is successful.[20][30][8]

Communication skills

editFor Berlo, communication skill is a wide term that includes encoding skills, decoding skills, and thinking skills. These skills are important for communication to succeed. They differ from communicator to communicator and also from situation to situation.[8] For verbal communication, Berlo discusses the encoding skills of writing and speaking as well as the decoding skills of reading and listening. But there are also many non-verbal communication skills, like the encoding skills of drawing and gesturing.[8][36] Berlo sees thought or reasoning as an additional communication skill relevant both to encoding and decoding.[37]

The communication skills required for successful communication are different for source and receiver. For the source, this includes the ability to express oneself or to encode the message in an accessible way.[8] Communication starts with a specific purpose and encoding skills are necessary to express this purpose in the form of a message. Good encoding skills ensure that the purpose is expressed very clearly and makes the decoding for the receiver much easier.[38][8] The relevant communication skills for the receiver include being able to decode the message correctly, such as listening and reading skills. If the receiver's communication skills are very limited, they may not be able to understand the expressions used by the source and thus not follow their train of thought.[8]

Attitudes

editAn attitude is a positive or negative stance the communicators take toward the topic of the communication, themselves, each other, or other relevant things.[8] Berlo defines attitude as "some predisposition, some tendency, some desire to either approach or avoid" an entity.[39]

He discusses three types of attitudes: the attitude the communicators have toward themselves, each other, and the subject matter. Various aspects of someone's personality belong to the attitude toward oneself like self-confidence. Communication tends to be more successful if the source has a positive attitude toward themselves. The attitude of the source toward the receiver concerns whether the source likes or dislikes the receiver and includes aspects of their past relation. These attitudes are a central factor for the fidelity of communication. Negative attitudes toward each other can make communication more adversarial than it would be otherwise. For example, if the source does not like the receiver, they may formulate a request in a rude manner or if the receiver does not like the source, they may reject an otherwise reasonable proposal. The attitude toward the subject matter concerns what the communicators think about the topic. For example, a salesperson who is convinced that their product is of high quality has a positive attitude toward the product. This attitude has a significant impact on their success as a salesperson when talking about the product to a prospective client.[40][8]

Knowledge

editAs a factor of communication, the knowledge is the understanding and familiarity the communicators have with the subject matter and to what they know of each other.[8] Without any knowledge, one cannot communicate and communication is very ineffective if the communicators' understanding is severely limited.[41] For the source, knowledge about the audience matters for making the message interesting and understandable to them. If the source knows much more than the receiver, there is always a danger of encoding the message in an overly technical vocabulary. The result can be that it is not understandable to a poorly informed receiver since they may be unable to decode the message. For example, to be a good teacher, one needs to have an in-depth knowledge of the subject but at the same time be able to explain it to someone with little knowledge.[42][8] Another aspect is knowledge of where the communication is taking place and how this situation might influence it.[8]

Social-cultural system

editBerlo uses the term "social-cultural system" to talk about the agent's position in their society and culture. It contrasts with the other factors (communication skills, attitudes, knowledge) since it is not just a mental factor: it depends not only on the person but also on their wider relations. It includes background beliefs and values common in this culture and ideas about what kinds of behavior are unacceptable. Within a culture, these aspects are also determined by the person's position within society, like their social class, which groups they belong to, and their more specific roles.[8][43]

The social-cultural system affects the purpose for which one communicates, the receiver and channel one chooses, what kind of content one transmits, and the words one selects to express this content. Such factors can influence how communicators behave, what guidelines they follow, what is being discussed, and how the contents are encoded and decoded. For example, there is a difference in how one talks to superiors and to peers. The communication styles of people with distinct social-cultural backgrounds can differ a lot. For example, Americans, Indonesians, Japanese, and Germans may differ both in what content they talk about and how they express them.[44][45][46] In cases of big social or cultural differences between source and receiver, effective communication is often severely limited.[8]

Message

editBerlo understands the message as a physical product of the source, like a speech, a written letter, or a painting. He holds that the message has three main factors: the code, the content, and the treatment. Each of these factors can be analyzed from two perspectives: based on the elements they use and based on the structure of how these elements are connected to each other.[47][48][45] The elements of a message are the signs and symbols used. For a newspaper article, the elements are the letters and words it contains. The structure of the message concerns the way these elements are arranged or to their order.[8] Many interpreters talk of five main features by counting elements and structure as separate factors.[17][19][1]

Berlo distinguishes between message and meaning. For him, communication is about the transmission of messages. Meaning, on the other hand, is personal to each participant and is relevant for the stages of en- and decoding. What meaning they associate with the message depends on various factors, including their past life experiences, their communication skills, their knowledge, and their culture. For this reason, they may associate different meanings with the message. For example, the source might think that the meaning of their message is of utmost importance while the receiver may dismiss it as trivial or irrelevant.[24][1]

Code

editOne of the subelements of the message is its code.[8] In communication theory, a code is a sign system to express information or a system of rules to convert information from one form into another.[49] Berlo defines code as "any group of symbols that can be structured in a way that is meaningful to some person". A code consists of two parts: a set of elements (vocabulary) and a set of rules for combining them (syntax).[50] For example, languages like English, Mandarin Chinese, or Swahili, are codes. Within each language, it is possible to distinguish between specialized codes, like the technical vocabulary used by physicists or neurologists. But there are also non-linguistic codes, like the ones involved, in music, dance, or visual art. Every message is expressed in some form of code. The choice of the appropriate code is central for ensuring that the receiver can understand the message and that it has the intended effect on them.[51][8][52]

For spoken language, the basic elements are sounds. They are grouped together to form phonemes and morphemes. For written English, the most basic elements are letters, like the letters "f", "h", "i", and "s". Letters can be combined to form a group with a structure. Some of these groups correspond to words, like "fish", while others do not, like "hsif". Words are formed by arranging letters in the right way.[53][8]

Content

editThe content of a message is what was selected by the source to express their communicative purpose. The elements of the content are single assertions and the content's structure is how these assertions are arranged, i.e. the order in which they are presented. The content is the information expressed in the message while the code is the way how it is expressed. The same content can often be expressed through different forms, for example, by translating it from one code into another. The source is responsible for selecting the appropriate content to communicate to the audience. This depends both on the communicative purpose of the source and on which content is useful to the receiver.[8][54]

Treatment

editThe source is presented with many choices when formulating the message. They concern the elements and the structure of both code and content. They include choosing which code to use, which information to express, and how to express it. The treatment corresponds to how the source decides in these cases. It reflects the style of the source as a communicator. This affects whether the chosen content and code are appropriate to the situation, the receiver, and the channel. For example, part of the job of a newspaper editor is to determine the treatment of the article. They do this by deciding how to express the ideas and how to arrange the sentences to make sure that they are easily understandable for the intended audience. In the case of cinema, the movie director has a similar task in deciding how to translate the screenplay into a movie.[8][55][56]

Channel

editFor Berlo, the term "channel" has a wide meaning. It refers both to the vehicle of an idea and to the carrier of this vehicle. But it also includes the processes that transfer the idea into the vehicle and then back into an idea. Berlo explains the channel in analogy to getting from one shore of a river to the other. The boat is the vehicle and the water is the vehicle carrier. Additionally, docks are needed on both sides to enter and leave the boat. In the case of oral communication, the docks are mechanisms of speaking and hearing, the soundwave is the vehicle corresponding to the boat, and the air is the vehicle carrier corresponding to the water. Berlo identifies the term channel with all of these components but puts the main emphasis on the vehicle and the vehicle carrier.[57][58][59] This takes the form of a discussion of the sensory processes involved in communication. They correspond to the five senses used to decode messages: seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting.[17][19][1]

The transmission is not restricted to one channel and may use several channels simultaneously. For example, a speaker may use their hands to give visual clues to the audience. This tends to increase the effectiveness of communication by promoting the receiver's understanding of the subject.[8] The choice of the right channel affects successful communication. For example, a classroom teacher has to decide which contents to present orally, by talking about them, and which ones to present visually through books. The choice also depends on the receiver whose decoding skills may be better for some channels than for others.[51][60]

Influence and applications

editThe SMCR model influenced the development of later models, often in the form of extensions to it. Marshall McLuhan extended the SMCR model by including interpretation as one of the steps of the receiver.[4] Gerhard Maletzke applied the SMCR model to mass communication in his 1978 book The Psychology of Mass Communication. He sees communication as a form of persuasion. He discusses factors influencing the behavior of the communicators and the outcome of the communication, like the image source and receiver have of each other.[4][61] Another application focuses on human behavior and intrapersonal communication in the context of organizations and management. It can be used, for example, to analyze employee behavior to identify and resolve human resource problems.[4] A similar application uses the SMCR model to analyze humorous messages at the workplace.[62]

Bette Ann Stead applies Berlo's model to content theories of motivation, like the ones by Abraham Maslow and Frederick Herzberg. According to Maslow's hierarchy of needs, lower and higher needs are the source of motivation. Frederick Herzberg contrasts intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. For intrinsic motivation, the activity is desired because it is enjoyable. Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, aims at external rewards.[63][64][65] Communication can fail if the source does not address the needs of the receiver on the right level. For example, an employer may try to motivate the employees by encoding the message in terms of lower-level needs. This attempt may fail if the employees decode this message as being about higher-level needs. A similar form of miscommunication can happen if the source encodes their message in terms of intrinsic motivation but the receiver decodes it in terms of extrinsic motivation.[63]

Criticism

editVarious criticisms of the SMCR model have been formulated. Many of them focus on the idea that it is "simple but effective" for some purposes but not complex enough to account for all forms of communication.[8] Berlo himself also acknowledged this problem in retrospect. He argued that the SMCR model was not intended as a comprehensive model of communication and may be better understood as an audiovisual tool to recall the main elements of communication.[4]

A lot of criticism of the SMCR model focuses on its description of communication as a one-way flow of information that starts with a source and ends with a receiver. In this regard, the model lacks a feedback loop.[4] While it may be sufficient for some types of communication, there are many situations where communication is a dynamic process of messages going back and forth between the participants. Berlo mitigates this criticism by claiming that the simplified presentation implying a linear nature is used mainly for convenience. At the same time, he holds that real communication is not a linear process consisting of a fixed sequence of events.[8][66][67]

Another common objection is that Berlo assumes that effective communication will take place. In this regard, it is simply presupposed that source and receiver are sufficiently similar on the level of communication skills, attitudes, knowledge, and social-cultural system for communication to succeed.[4][1] This means that the SMCR model fails to properly address the effects of noise and other barriers that may inhibit the transmission of the message or distort it along the way.[1]

Hal Taylor criticizes Berlo's model by holding that it does not put enough emphasis on "the purposive nature of human communication". This criticism is based on the idea that the source usually intends to achieve some purpose by engaging in communication, like persuading the audience or getting them to perform a certain action. Berlo himself acknowledges the role of a purpose guiding communication but his model does not include an separate component corresponding to this factor.[8][9]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tengan, Aigbavboa & Thwala 2021, p. 94.

- ^ Dwyer 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Gibson 2013, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pande 2020, pp. 1588–1589, SMCR Model.

- ^ Straubhaar, LaRose & Davenport 2015, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Harrington & Terry 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Berlo 1960, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Taylor 1962, pp. 8–10.

- ^ a b c d Jandt 2010, p. 41.

- ^ Zaharna 2022, p. 70.

- ^ Pollock 1976, p. 24.

- ^ Berlo 1960, p. 11.

- ^ Berlo 1960, p. 12.

- ^ Berlo 1960, p. 13.

- ^ a b UMN staff 2016, 1.1 Communication: History and Forms.

- ^ Berlo 1960, pp. 15–18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Januszewski 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Rogers 1986, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e Narula 2006, 1. Basic Communication Models.

- ^ a b c Mannan 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Shannon 1948, pp. 379–423.

- ^ Chandler & Munday 2011a, Shannon and Weaver's model.

- ^ Ruben 2001, Models Of Communication.

- ^ a b c d Moore 1994, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b c Schramm 1960, pp. 3–26, How communication works.

- ^ Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 176.

- ^ Dwyer 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Blythe 2009, pp. 177–180.

- ^ Carney & Lymer 2015, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Agunga 2006, p. 381.

- ^ a b Nwankwo & Aiyeku 2002, p. 211.

- ^ Hood 2013, p. 81.

- ^ Chesebro & Bertelsen 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Berlo 1960, pp. 30–31, 41.

- ^ Eadie 2021, p. 31.

- ^ Schnell 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Cotterman, Forsberg & Mooz 2005, p. 49.

- ^ Bettinghaus 2000, p. 29.

- ^ Berlo 1960, p. 45.

- ^ Berlo 1960, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Bettinghaus 2000, p. 30.

- ^ Berlo 1960, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Bettinghaus 2000, pp. 30–1.

- ^ Halder & Saha 2023, p. 93.

- ^ a b Bhatnagar 2011, p. 105.

- ^ Berlo 1960, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Pathak 2012, p. 166.

- ^ Johnson 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Chandler & Munday 2011, code.

- ^ Lawson et al. 2019, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Dove 2020, p. 62.

- ^ Berlo 1960, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Berlo 1960, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Helen, Caroline & Karen 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Lawson et al. 2019, p. 76.

- ^ Okazaki 2012, p. 26.

- ^ Halder & Saha 2023, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Dowling et al. 2020, p. 270.

- ^ Berlo 1960, pp. 63–69.

- ^ Berlo 1960, p. 67.

- ^ Huebsch 2014, p. 54.

- ^ Scott & Lewis 2017.

- ^ a b Stead 1972, pp. 389–394.

- ^ Salkind & Rasmussen 2008, p. 634.

- ^ Silverthorne 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Lane 2005, p. 3.

- ^ Powell & Powell 2015, p. 20.

Sources

edit- Agunga, Robert (2006). Communication for Social Change Anthology: Historical and Contemporary Readings. CFSC Consortium, Inc. p. 381. ISBN 9780977035793.

- Berlo, David K. (1960). The Process of Communication: An Introduction to Theory and Practice. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 9780030074905.

- Bettinghaus, Erwin P. (1 September 2000). Research, Principles and Practices in Visual Communication. Information Age Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60752-954-5.

- Bhatnagar, Nitin (2011). Effective Communication and Soft Skills. Pearson Education India. p. 105. ISBN 978-93-325-0129-4.

- Blythe, Jim (5 March 2009). Key Concepts in Marketing. SAGE Publications. pp. 177–80. ISBN 9781847874986.

- Carney, William Wray; Lymer, Leah-Ann (5 August 2015). Fundamentals of Public Relations and Marketing Communications in Canada. University of Alberta. p. 91. ISBN 9781772120622.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (10 February 2011). "code". A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199568758.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (10 February 2011a). "Shannon and Weaver's model". A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199568758.

- Chesebro, James W.; Bertelsen, Dale A. (1 October 1998). Analyzing Media: Communication Technologies as Symbolic and Cognitive Systems. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-57230-419-2.

- Cotterman, Howard; Forsberg, Kevin; Mooz, Hal (11 November 2005). Visualizing Project Management: Models and Frameworks for Mastering Complex Systems. John Wiley & Sons. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-471-74674-4.

- Dove, Martina (29 December 2020). The Psychology of Fraud, Persuasion and Scam Techniques: Understanding What Makes Us Vulnerable. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-000-33402-9.

- Dowling, David; Hadgraft, Roger; Carew, Anna; McCarthy, Tim; Hargreaves, Doug; Baillie, Caroline; Male, Sally (21 January 2020). Engineering Your Future: An Australasian Guide, 4th Edition. John Wiley & Sons. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-7303-6916-5.

- Dwyer, Judith (15 October 2012). Communication for Business and the Professions: Strategie s and Skills. Pearson Higher Education AU. p. 10. ISBN 9781442550551.

- Eadie, William F. (5 November 2021). When Communication Became a Discipline. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4985-7216-3.

- Gibson, Pattie (28 May 2013). The World of Customer Service. Cengage Learning. p. 140. ISBN 9781133708476.

- Halder, Santoshi; Saha, Sanju (10 March 2023). The Routledge Handbook of Education Technology. Taylor & Francis. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-000-59526-0.

- Harrington, Nicki; Terry, Cynthia Lee (1 January 2008). LPN to RN Transitions: Achieving Success in Your New Role. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-7817-6757-6.

- Helen, Iggulden; Caroline, Macdonald; Karen, Staniland (1 March 2009). Clinical Skills: The Essence Of Caring: The Essence of Caring. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). p. 8. ISBN 978-0-335-22355-8.

- Hood, Lucy (26 November 2013). Leddy & Pepper's Conceptual Bases of Professional Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 81. ISBN 9781469831916.

- Huebsch, J. C. (20 May 2014). Communication 2000. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 54. ISBN 9781483141954.

- Jandt, Fred Edmund (2010). An Introduction to Intercultural Communication: Identities in a Global Community. SAGE. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4129-7010-5.

- Januszewski, Alan (2001). Educational Technology: The Development of a Concept. Libraries Unlimited. p. 30. ISBN 9781563087493.

- Johnson, J. David (1 October 2009). Managing Knowledge Networks. Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-139-48223-3.

- Lane, LeRoy L. (3 May 2005). By All Means Communicate: An Overview of Basic Speech Communication; Second Edition. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-59752-168-0.

- Lawson, Celeste; Gill, Robert; Feekery, Angela; Witsel, Mieke (12 June 2019). Communication Skills for Business Professionals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-59441-7.

- Littlejohn, Stephen W.; Foss, Karen A. (18 August 2009). Encyclopedia of Communication Theory. SAGE Publications. p. 176. ISBN 9781412959377.

- Mannan, Zahed (20 October 2013). Business Communication: Strategies for Success in Business and Professions. University Grants Commission, Bangladesh. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-495-56764-6.

- Moore, David Mike (1994). Visual Literacy: A Spectrum of Visual Learning. Educational Technology. pp. 90–1. ISBN 9780877782643.

- Narula, Uma (2006). "1. Basic Communication Models". Handbook of Communication Models, Perspectives, Strategies. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 11–44. ISBN 9788126905133.

- Nwankwo, Sonny; Aiyeku, Joseph F. (2002). Dynamics of Marketing in African Nations. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-56720-399-8.

- Okazaki, Shintaro (1 January 2012). Handbook of Research on International Advertising. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-78100-104-2.

- Pande, Navodita (2020). "SMCR Model". The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society. SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 1588–1589. doi:10.4135/9781483375519. hdl:10400.19/6285. ISBN 9781483375533. S2CID 213132710.

- Pathak, R. P. (2012). Educational Technology. Pearson Education India. p. 166. ISBN 978-81-317-5429-0.

- Pollock, C. Daniel (1976). The Art and Science of Psychological Operations: Case Studies of Military Application. Headquarters, Department of the Army. p. 24.

- Powell, Robert G.; Powell, Dana L. (16 September 2015). Classroom Communication and Diversity: Enhancing Instructional Practice. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-317-48426-4.

- Rogers, Everett M. (11 June 1986). Communication Technology. Simon and Schuster. p. 89. ISBN 9780029271209.

- Ruben, Brent D. (2001). "Models Of Communication". Encyclopedia of Communication and Information. ISBN 9780028653860.

- Salkind, Neil J.; Rasmussen, Kristin (17 January 2008). Encyclopedia of Educational Psychology. SAGE. p. 634. ISBN 9781412916882.

- Schnell, James A. (2001). Qualitative Method Interpretations in Communication Studies. Lexington Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7391-0147-6.

- Schramm, Wilbur (1960) [1954]. "How communication works". The Process and Effects of Mass Communication. University of Illinois Press. pp. 3–26. ISBN 9780252001970.

- Scott, Craig; Lewis, Laurie (6 March 2017). The International Encyclopedia of Organizational Communication, 4 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118955604.

- Shannon, C. E. (July 1948). "A Mathematical Theory of Communication". Bell System Technical Journal. 27 (3): 379–423. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x.

- Silverthorne, Colin P. (1 January 2005). Organizational Psychology in Cross Cultural Perspective. NYU Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780814739860.

- Stead, Bette Ann (1972). "Berlo's Communication Process Model as Applied to the Behavioral Theories of Maslow, Herzberg, and McGregor". The Academy of Management Journal. 15 (3): 389–394. doi:10.2307/254868. ISSN 0001-4273. JSTOR 254868.

- Straubhaar, Joseph; LaRose, Robert; Davenport, Lucinda (1 January 2015). Media Now: Understanding Media, Culture, and Technology. Cengage Learning. pp. 18–9. ISBN 9781305533851.

- Taylor, Hal R. (1962). "A Model for the Communication Process". STWP Review. 9 (3): 8–10. ISSN 2376-0761. JSTOR 43093688.

- Tengan, Callistus; Aigbavboa, Clinton; Thwala, Wellington Didibhuku (27 April 2021). Construction Project Monitoring and Evaluation: An Integrated Approach. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 9781000381412.

- UMN staff (29 September 2016). "1.1 Communication: History and Forms". Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. ISBN 9781946135070.

- Zaharna, R. S. (2022). Boundary Spanners of Humanity: Three Logics of Communications and Public Diplomacy for Global Collaboration. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780190930271.