The black-and-white owl (Strix nigrolineata) is a species of owl in the family Strigidae.[1][3]

| Black-and-white owl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Strigidae |

| Genus: | Strix |

| Species: | S. nigrolineata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Strix nigrolineata (Sclater, PL, 1859)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ciccaba nigrolineata (Sclater, 1859) | |

Description

editThe black-and-white owl is a medium-sized owl with a round head and no ear tufts. It is between 35 and 40 cm in length and weigh between 400 and 535 grams. As for most owl species, females are usually bigger than males with an average weight of 487 g and 418 g respectively.[4] It has a striped black-and-white breast, belly, and vent. With the exception of a black-and white striped collar, the upperparts from the crown to the tail are a sooty black. The facial disc is mostly sooty black, with white "eyebrows" that extend from the bill to the collar. The beak is a yellow-orange colour, and the eyes are a reddish brown.[5]

Chicks are downy and white.

Juveniles have a whitish face, dark brown upper-parts and a white-barred black underside.[6]

Taxonomy

editFormerly under the genus Ciccaba which includes many neotropical species, the black-and-white owl is now classified under the genus Strix known as the "wood owls", which all share the same round head and pitch black eyes.[4] This raptor was first reported in 1859 by Sclater. Its sister species, the black-banded owl (Strix hulula), while being similar, is smaller and has a darker plumage. Plus, it occupies a different range which includes the southern tropical forests of South America.[7][4]

Habitat

editThe black-and-white owl is mostly found in gallery forests and rainforest, but is also found in wet deciduous and mangrove forests, usually at an altitude between sea level and 2400 meters.[5] Small ponds are also often visited by this species when hunting. It usually nests in the foliage of large, tall trees such as mahogany.[4][8] This owl is not afraid of living near human habitations.[5]

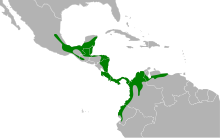

Distribution

editIts range extends from central Mexico south to the northwestern section of Peru and western Colombia, a range it partially shares with another related species: the mottled owl (Strix virgata).[8][5] In total, it is found in 12 countries: Belize, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela.[1] This bird of prey also stays faithful to its range all year long as it is a non-migratory bird.[4]

Behaviour

editForaging and diet

editThis neotropical bird is a nocturnal hunter and since most of its prey can fly, it forages mostly at the canopy level of its habitat. It will first examine its surroundings by perching on an elevated branch. Then it will make short, silent flights to catch its food.[9][10] Primarily insectivorous, the black-and-white owl prefers scarab beetles (Scarabaedidae) such as dung beetles and sometimes prey upon orthopterans and cicadas (Cicadidae).[9][10] Bats such as the Jamaican fruit bat (Artibeus jamaicensis) and other small rodents also make up a large part of its diet. Furthermore, it can occasionally feed on smaller birds like trushes and tanagers as well as amphibians.[7][9][10] It is also one of the only tropical owl species reported to capture barn swallows since those are easy to catch when roosting on nearby electric lines.[11]

Vocalization

editIts call consists of a series of rapid, guttural, low calls, followed by a short pause and a low, airy call and a faint, short hoot. Occasionally, it is shortened to just the last two notes, leaving out the opening series.[5] Moreover, the female's call usually sounds louder than the male's and individuals make fainter "hoots" near their nest. Just like their parents, younglings can produce strident cries, but also communicate by clacking their beak.[4]

Reproduction

editWhen the breeding season begins in March, the monogamous pair forms after the male successfully seduces the female with wing flaps and elaborated acrobatic flights.[6][8] Then, before the severe downpours begin, the couple settles on an isolated tree to protect their offspring from climbing predators and use epiphytes and flower arrangements (e.g., orchids) as their nest.[4][8] While the female incubates the clutch of one or two eggs, the male goes foraging for the pair and fiercely defends the nest, even from nearby humans. Sometimes, the female will tag along with her mate when she is not coveting.[6][8][9] The eggs are dull, whitish and weight about 33.8 g (usually 6% of the female's body mass) with an average length and width of 46.4 and 38.4 mm (1.83 and 1.51 in) respectively.[4][12] The black-and-white owl is one of the only owls to lay a single egg which relates to the fact that clutch size lowers as a species lives closer to the Equator, thus explaining its low reproductive success.[8] After an incubation period of at least 30 days, the chicks hatch in April.[4][8] They harbour white down feathers, pink feet and beak and weight around 28 g after 2 days. They first open their eyes at 14 days old as the black bars on their wings start to develop. Chicks also have a low chance of survival as they can be preyed upon by tayras, ocelots, coatis, falcons and hawks.[4]

Conservation status and threats

editThe black-and-white owl is classified as "Least Concern" on IUCN's Red List even if its populations are decreasing.[13] Mexico's population in particular observed a decline of 50% in the last century which has made the species a big concern for the Partners in Flight association.[7] This bird of prey's main threat is the loss of its wetland and forest habitats which are progressively converted into agricultural lands.[4][7] Human proximity also causes their populations to decrease.[4]

References

edit- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2018). "Ciccaba nigrolineata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22689133A130159025. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22689133A130159025.en. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Compare with ITIS: "Ciccaba nigrolineata". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jenny, J. Peter (15 May 2013). Whitacre, David (ed.). Neotropical Birds of Prey: Biology and Ecology of a Forest Raptor Community. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9780801464287. ISBN 978-0-8014-6428-7.

- ^ a b c d e Mikkola, Heimo (2012). Owls of the World. Buffalo, New York: Firefly. p. 333.

- ^ a b c "Black-and-white Owl". oiseaux-birds.com. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Stearns, Anna (4 March 2020). Schulenberg, Thomas S (ed.). "Black-and-white Owl (Ciccaba nigrolineata)". Birds of the World. doi:10.2173/bow.bawowl1.01.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gerhardt, Richard P.; González, Normandy Bonilla; Gerhardt, Dawn McAnnis; Flatten, Craig J. (1994). "Breeding Biology and Home Range of Two Ciccaba Owls". The Wilson Bulletin. 106 (4): 629–639. ISSN 0043-5643. JSTOR 4163480.

- ^ a b c d Gerhardt, Richard P.; Gerhardt, Dawn McAnnis; Flatten, Craig J.; González, Normandy Bonilla (1994). "The Food Habits of Sympatric Ciccaba Owls in Northern Guatemala (Los Hábitos Alimenticios de Lechuzas del Género Ciccaba en el Norte de Guatemala)". Journal of Field Ornithology. 65 (2): 258–264. ISSN 0273-8570. JSTOR 4513935.

- ^ a b c Ibañez, Carlos; Ramo, Cristina; Busto, Benjamín (1992). "Notes on Food Habits of the Black and White Owl". The Condor. 94 (2): 529–531. doi:10.2307/1369226. hdl:10261/49106. ISSN 0010-5422. JSTOR 1369226.

- ^ Sandoval, Luis; Biamonte, Esteban; Solano-Ugalde, Alejandro (March 2008). "Previously Unknown Food Items in the Diet of Six Neotropical Bird Species". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 120 (1): 214–216. doi:10.1676/07-012.1. ISSN 1559-4491. S2CID 83657346.

- ^ Gerhardt, Richard P.; Gerhardt, Dawn McAnnis (1997). "Size, dimorphism, and related characteristics of Ciccaba owls from Guatemala". In Duncan, James R.; Johnson, David H.; Nicholls, Thomas H. (eds.). Biology and conservation of owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd International symposium. St. Paul, MN: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station. pp. 190–196.

- ^ International), BirdLife International (BirdLife (6 August 2018). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Ciccaba nigrolineata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 14 October 2020.