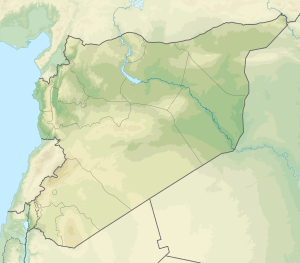

Bouqras is a large, oval shaped, prehistoric, Neolithic Tell, about 5 hectares (540,000 sq ft) in size, located around 35 kilometres (22 mi) from Deir ez-Zor in Syria.[1]

| |

| Location | 35 km (22 mi) southeast of Deir ez-Zor, Syria |

|---|---|

| Region | Euphrates |

| Coordinates | 35°05′07″N 40°23′51″E / 35.085274°N 40.397445°E |

| Type | Tell |

| Part of | Village |

| Length | 250 metres (820 ft) |

| Width | 100 metres (330 ft) |

| Area | 5 hectares (540,000 sq ft) |

| History | |

| Material | bones, flints, pottery, plaster |

| Founded | c. 7400 |

| Abandoned | c. 6200 BC |

| Periods | PPNA, PPNB, Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1960-1965 1976-1978 |

| Archaeologists | Henri de Contenson Willem J. van Liere Peter Akkermans Maurits van Loon J. J. Roodenberg H. T. Waterbolk |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Management | Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums |

| Public access | Yes |

Excavation

editThe tell was discovered in 1960 by Dutch geomorphologist, Willem van Liere. It was excavated between 1960 and 1965 by Henri de Contenson and van Liere and later between 1976 and 1978 by Peter Akkermans, Maurits van Loon, J. J. Roodenberg and H. T. Waterbolk.[1]

Construction

editThe mound was found to be approximately 4.5 metres (15 ft) deep and showed evidence of 11 periods of occupation spread over at least 1000 years between ca. 7400 and 6200 BC. The earliest levels, 11 to 8, showed early Neolithic aceramic occupation developing on to stages with pottery in levels 7 to 1, from which over 7000 sherds were recovered. Material from later levels was visible on the surface when first discovered.[1] The layout and arrangement of houses seems to have been well ordered with similar arrangements of rooms, entrances, hearths and other features. Houses were made of mud bricks and generally rectangular with three or four rooms.[2]

Culture

editBouqras seems to have developed in comparative isolation with few other settlements near the area. Interiors of the buildings featured white plastered walls with occasional use of red ochre for decoration with some images of birds. By later stages of the settlement, it was likely inhabited by as many as 700 to 1000 villagers.[1] Large quantities of obsidian was found suggesting links with Anatolia.[2] A distinctive group of limestone, alabaster and gypsum vessels was also found made from local materials.[3] Rounded or cylindrical beads were also found made of bone, shell, greenstones, carnelian and dentalium. An alabaster bracelet fragment and pendant were recovered as forms of personal decoration.[3] Several stone stamp seals including one of alabaster and one of jadeite were found with incised rectilinear patterns along with a few clay figurines. Pottery started to be found from the third level of habitation including a white plaster vessel. Other materials were varied with coarse and fine sherds made with mixed straw and sand. Some sherds were burnished or painted red, one with a triangle on it.[3] Arrowheads recovered included Byblos points and two types of Amuq points along with two other distinctive designs.[4] Flints were usually of a fine dark grey or brown type found locally.[3]

-

Stone Bowl, Syria, probably Bouqras, ca. late 8th millennium BC.

-

Calcite tripod vase, mid-Euphrates, probably from Tell Buqras, 6000 BC, Louvre Museum AO 31551

-

Alabaster pot with handles, Buqras region, 6500 BCE Louvre Museum AO 28519

-

Alabaster pot Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Alabaster pot, Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Footed bowl in granite, Syria, end of 8th millennium BC.

-

Jar in calcite alabaster, Syria, late 8th millennium BC.

-

Wall painting in a Neolithic house in Tell Bouqras. Deir ez-Zor Museum (copy).[5]

Agriculture and animal domestication

editPaleobotanical studies were carried out by Willem van Zeist on carbonized plant remains recovered via water flotation. This has shown rain fed agriculture was practiced at Bouqras including cultivation of Emmer, Einkorn and free-threshing wheat, naked and hulled barley, peas and lentils.[6][7] Sickle blades, querns and pounders appear in the early stages at Bouqras, but not in later stages. White Ware was found suggested to have been used as basket covering to make them impermeable.[2]

Sheep and goat comprised approximately 80% of the 5800 identifiable fragments of animal remains found. Other fauna included pigs and cattle, the domestication of which is uncertain. Deer, gazelle and onager were also hunted.[8]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Peter M. M. G. Akkermans; Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The archaeology of Syria: from complex hunter-gatherers to early urban societies (c. 16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0-521-79666-8. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. pp. 176–178.

- ^ a b c d Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. pp. 176–180.

- ^ J. J. Roodenberg (1986). Le mobilier en pierre de Bouqras. Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te İstanbul. ISBN 978-90-6258-061-3. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Brockschmidt, Rolf (2 June 2015). "Wissen ist stärker als die Zerstörungswut des IS". www.tagesspiegel.de (in German). Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Van Zeist W. , Waterbolk-Van-Rooijen W., Paleorient, Volume 11/2, The Palaeobotany of Tell Bouqras, Eastern Syria, 1985.

- ^ Corinne Julien (2000). Histoire de l'humanité: De la préhistoire aux débuts de la civilisation. UNESCO. pp. 1043–. ISBN 978-92-3-202810-5. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Sytze Bottema; International Union for Quaternary Research; Rijksuniversiteit te Groningen. Biologisch-Archeologisch Instituut (1990). Man's role in the shaping of the eastern Mediterranean landscape: proceedings of the INQUA/BAI Symposium on the Impact of Ancient Man on the Landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean Region and the Near East, Groningen, Netherlands, 6-9 March 1989. Taylor & Francis. pp. 199–. ISBN 978-90-6191-138-8. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

Further reading

edit- de Contenson, H., van Liere, W.J., A Note on Five Early Neolithic Sites in Inland Syria 13, 175–209, 1963.

- de Contenson, Henri, & van Liere, Willem, Premier sondage à Bouqras en 1965. Rapport préliminaire, Annales Archéologiques Arabes Syriennes XVI 2, 1966, p. 181-192.

- de Contenson, H., Découvertes récentes dans la domaine du Néolithique en Syrie, L'Anthropologie, 70, 388–391, 1966.

- Vogel, J.C., Waterbolk, H.T., Groningen Radiocarbon Dates VII, Radiocarbon, 9, 107–155, 1967.

- Clason, A.T., The Animal Remains from Tell Es Sinn Compared with those from Bouqras, Anatolica, 7, 35–53, 1980.

- Akkermans, P.A., Fokkens, H., Waterbolk, H.T., Stratigraphy, architecture and layout of Bouqras in Cauvin, J. and Sanlaville (eds.) 1981, Préhistore du Levant: Chronologie et organisation de l´éspace depuis les origines jusqu´au VIe millenaire, Colloque International du CNRS, Lyon 1980, Paris, 485–502, 1981.

- Akkermans, P.A., Boerma, J.A.K., Clason, A.T., Hill, S.G., Lohof, E., Meiklejohn, C., Le Mière, M., Molgat, G.M.F., Roodenberg, J., Waterbolk-van Rooijen, W., van Zeist, W., Bouqras Revisited: Preliminary Report on a Project in Eastern Syria. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 49, 335–372, 1983.

- de Contenson, Henri, La campagne de 1965 à Bouqras, Cahiers de l'Euphrate, 4, 335–371, 1985.

- Roodenberg, J., Le mobilier en pierre de Bouqras. Utilisation de la pierre dans un site néolithique sur le Mayen Euphrate (Syrie) Leiden/Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut, 1986.

- Lohof, E., A lesser known figurine from the near eastern Neolithic, Haex et al. (eds.) 1989 in To the Euphrates and Beyond: Archaeological Studies in Honour of Maurits N. van Loon, Balkema, Rotterdam, 65–74, 1989.

- Clason, A.T., The Bouqras Bird Frieze, Anatolica, 16, 209–213, 1990.

- Boerma, J.A.K., Palaeo Environment and Palaeo Land-Evaluation Based on Actual Environment Conditions of Tell Bouqras, East Syria, Anatolica, 16, 215–249, 1990.

- Bernbeck, R., Die Auflösung der häuslichen Produktionsweise, Berliner Beiträge zum Vorderen Orient 14 (Ph.D. dissertation Berlin, Freie Univ. 1991), Berlin, 1994.