Bovine serum albumin (BSA or "Fraction V") is a serum albumin protein derived from cows. It is often used as a protein concentration standard in lab experiments.

| albumin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | ALB | ||||||

| Entrez | 280717 | ||||||

| HomoloGene | 105925 | ||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | NM_180992 | ||||||

| RefSeq (Prot) | NP_851335 | ||||||

| UniProt | P02769 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Chromosome | 6: 91.54 - 91.57 Mb | ||||||

| |||||||

The nickname "Fraction V" refers to albumin being the fifth fraction of the original Edwin Cohn purification methodology that made use of differential solubility characteristics of plasma proteins. By manipulating solvent concentrations, pH, salt levels, and temperature, Cohn was able to pull out successive "fractions" of blood plasma. The process was first commercialized with human albumin for medical use and later adopted for production of BSA.

Properties

editThe full-length BSA precursor polypeptide is 607 amino acids (AAs) in length. An N-terminal 18-residue signal peptide is cut off from the precursor protein upon secretion, hence the initial protein product contains 589 amino acid residues. An additional six amino acids are cleaved to yield the mature BSA protein that contains 583 amino acids.[1]

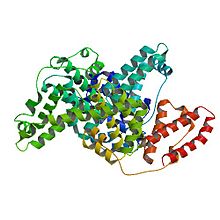

BSA has three homologous but structurally different domains. The domains, named I, II, and III, are broken down into two sub-domains, A and B.[1]

| Peptide | Position | Length (AAs) | MW Da |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full length precursor | 1 – 607 | 607 | 69,324 |

| Signal peptide | 1 – 18 | 18 | 2,107 |

| Propeptide | 19 – 24 | 6 | 478 |

| Mature protein | 25 – 607 | 583 | 66,463 |

Physical properties of BSA:

- Number of amino acid residues: 583

- Molecular weight: 66,463 Da (= 66.5 kDa)

- isoelectric point in water at 25 °C: 4.7[2]

- Extinction coefficient of 43,824 M−1cm−1 at 279 nm[3]

- Dimensions: 140 × 40 × 40 Å (prolate ellipsoid where a = b < c)[4]

- pH of 1% Solution: 5.2-7 [5][6]

- Optical Rotation: [α]259: -61°; [α]264: -63°[5][6]

- Stokes Radius (rs): 3.48 nm[7]

- Sedimentation constant, S20,W × 1013: 4.5 (monomer), 6.7 (dimer)[5][6]

- Diffusion constant, D20,W × 10−7 cm2/s: 5.9[5][6]

- Partial specific volume, V20: 0.733[5][6]

- Intrinsic viscosity, η: 0.0413[5][6]

- Frictional ratio, f/f0: 1.30[5][6]

- Refractive index increment (578 nm) × 10−3: 1.90[5][6]

- Optical absorbance, A279 nm1 g/L: 0.667[5][6]

- ε280 = 43.824 mM−1 cm−1 [8]

- Mean residue rotation, [m']233: 8443[5][6]

- Mean residue ellipticity: 21.1 [θ]209 nm; 20.1 [θ]222 nm[5][6]

- Estimated a-helix, %: 54[5][6]

- Estimated b-form, %: 18[5][6]

Function

editBSA, like other serum albumins, is critical in providing oncotic pressure within capillaries, transporting fatty acids, bilirubin, minerals and hormones, and functioning as both an anticoagulant and an antioxidant.[9] There are approximately 6 different long chain fatty acid binding sites on the protein, the three strongest of which are located one per each domain. BSA can also bind other substances such as salicylate, sulfonamides, bilirubin, and other drugs, which bind to “site 1” in subdomain IIA, while tryptophan, thyroxine, octanoate and other drugs that are aromatic in nature bind to “site 2” in subdomain IIIA.[10]

Applications

editBSA is often used as a model for other serum albumin proteins, especially human serum albumin, to which it is 76% structurally homologous.[11]

BSA has numerous biochemical applications including ELISAs (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay), immunoblots, and immunohistochemistry. Because BSA is a small, stable, moderately non-reactive protein, it is often used as a blocker in immunohistochemistry.[12] During immunohistochemistry, which is the process that uses antibodies to identify antigens in cells, tissue sections are often incubated with BSA blockers to bind nonspecific binding sites.[13][14] This binding of BSA to nonspecific binding sites increases the chance that the antibodies will bind only to the antigens of interest.[15] The BSA blocker improves sensitivity by decreasing background noise as the sites are covered with the moderately non-reactive protein.[16][17] During this process, minimization of nonspecific binding of antibodies is essential in order to acquire the highest signal to noise ratio.[16] BSA is also used as a nutrient in cell and microbial culture. In restriction digests, BSA is used to stabilize some enzymes during the digestion of DNA and to prevent adhesion of the enzyme to reaction tubes, pipette tips, and other vessels.[18] This protein does not affect other enzymes that do not need it for stabilization. BSA is also commonly used to determine the quantity of other proteins, by comparing an unknown quantity of protein to known amounts of BSA (see Bradford protein assay). BSA is used because of its ability to increase signal in assays, its lack of effect in many biochemical reactions, and its low cost, since large quantities of it can be readily purified from bovine blood, a byproduct of the cattle industry. Another use for BSA is that it can be used to temporarily isolate substances that are blocking the activity of the enzyme that is needed, thus impeding polymerase chain reaction (PCR).[19] BSA has been widely used as a template to synthesize nanostructures [20] and determining the toxic or beneficial effects of metal ions and their complexes.[21]

BSA is also the main constituent of fetal bovine serum, a common cell culture medium.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Majorek KA, Porebski PJ, Dayal A, Zimmerman MD, Jablonska K, Stewart AJ, et al. (October 2012). "Structural and immunologic characterization of bovine, horse, and rabbit serum albumins". Molecular Immunology. 52 (3–4): 174–182. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2012.05.011. PMC 3401331. PMID 22677715.

- ^ Ge S, Kojio K, Takahara A, Kajiyama T (1998). "Bovine serum albumin adsorption onto immobilized organotrichlorosilane surface: influence of the phase separation on protein adsorption patterns". Journal of Biomaterials Science. Polymer Edition. 9 (2): 131–150. doi:10.1163/156856298x00479. PMID 9493841.

- ^ Peters T (1975). Putman FW (ed.). The Plasma Proteins. Academic Press. pp. 133–181.

- ^ Wright AK, Thompson MR (February 1975). "Hydrodynamic structure of bovine serum albumin determined by transient electric birefringence". Biophysical Journal. 15 (2 Pt 1): 137–141. Bibcode:1975BpJ....15..137W. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(75)85797-3. PMC 1334600. PMID 1167468.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Putnam FW (1975). The Plasma Proteins: Structure, Function and Genetic Control. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). New York: Academic Press. pp. 141, 147. ASIN B007ESU1JQ.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Albumin from bovine serum" (PDF). Sigma-Aldrich. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ Axelsson I (May 1978). "Characterization of proteins and other macromolecules by agarose gel chromatography". Journal of Chromatography A. 152 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)85330-3.

- ^ "TECH TIP #6 Extinction Coefficients" (PDF). Thermo Fisher Scientific. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Chen CB, Hammo B, Barry J, Radhakrishnan K (July 2021). "Overview of Albumin Physiology and its Role in Pediatric Diseases". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 23 (8): 11. doi:10.1007/s11894-021-00813-6. PMID 34213692.

- ^ Peters T (1996). All about albumin : biochemistry, genetics, and medical applications. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-552110-9. OCLC 162129148.

- ^ Topală T, Bodoki A, Oprean L, Oprean R (2014-11-12). "Bovine Serum Albumin Interactions with Metal Complexes". Clujul Medical. 87 (4): 215–219. doi:10.15386/cjmed-357. PMC 4620676. PMID 26528027.

- ^ "Serum Albumins and Allergies". Structural Biology Knowledgebase. National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. October 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ^ "What Is Immunohistochemistry (IHC)". Immunohistochemistry. Sino Biological Inc.

- ^ Farwell AP, Dubord-Tomasetti SA (September 1999). "Thyroid hormone regulates the expression of laminin in the developing rat cerebellum". Endocrinology. 140 (9): 4221–4227. doi:10.1210/endo.140.9.7007. PMID 10465295.

- ^ "Tips for Reducing ELISA Background". Biocompare. Compare Networks. October 8, 2012.

- ^ a b Ouellet M (December 24, 2006). "How Blocking Works in Immunocytochemical Analysis with Serum or BSA". MadSci Network: Biochemistry. MadSci Network.

- ^ "Blocker™ BSA (10X) in PBS". Thermo Fisher Scientific. Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30.

- ^ "BSA FAQ". Invitrogen. Archived from the original on 2011-12-28. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ Kreader CA (March 1996). "Relief of amplification inhibition in PCR with bovine serum albumin or T4 gene 32 protein". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 62 (3): 1102–1106. Bibcode:1996ApEnM..62.1102K. doi:10.1128/aem.62.3.1102-1106.1996. PMC 167874. PMID 8975603.

- ^ Rahmani T, Hajian A, Afkhami A, Bagheri H (2018). "A novel and high performance enzyme-less sensing layer for electrochemical detection of methyl parathion based on BSA templated Au–Ag bimetallic nanoclusters". New Journal of Chemistry. 42 (9): 7213–22. doi:10.1039/C8NJ00425K.

- ^ Zavalishin MN, Pimenov OA, Belov KV, Khodov IA, Gamov GA (November 2023). "Chemical equilibria in aqueous solutions of H[AuCl4] and bovine or human serum albumin". Journal of Molecular Liquids. 389: 122914. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122914.

Further reading

edit- Hirayama K, Akashi S, Furuya M, Fukuhara K (December 1990). "Rapid confirmation and revision of the primary structure of bovine serum albumin by ESIMS and Frit-FAB LC/MS". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 173 (2): 639–646. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(05)80083-X. PMID 2260975.

- Zhang M, Desai T, Ferrari M (May 1998). "Proteins and cells on PEG immobilized silicon surfaces". Biomaterials. 19 (10): 953–960. doi:10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00026-X. PMID 9690837.[permanent dead link]

- Wise SA, Watters RL (2010-06-30). "Bovine Serum Albumin (7 % Solution)" (pdf). Certificate of Analysis. United States National Institute of Standards & Technology. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

External links

edit- Serum+Albumin,+Bovine at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)