The Centaurus was the final development of the Bristol Engine Company's series of sleeve valve radial aircraft engines. The Centaurus is an 18-cylinder, two-row design that eventually delivered over 3,000 hp (2,200 kW). The engine was introduced into service late in the Second World War and was one of the most powerful aircraft piston engines to see service.

| Centaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

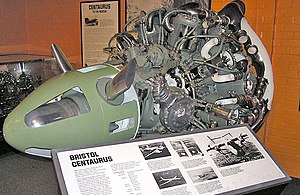

| Bristol Centaurus engine cutaway | |

| Type | Piston aircraft engine |

| Manufacturer | Bristol Aeroplane Company |

| First run | July 1938 |

| Major applications | Hawker Tempest Bristol Brabazon Vickers Warwick Hawker Sea Fury Airspeed Ambassador |

| Number built | c. 2,500 |

Design and development

editLike other Bristol sleeve valve engines, the Centaurus was based on the design knowledge acquired from an earlier design, in this case the Bristol Perseus cylinder. The Centaurus used 18 Perseus cylinders. The same cylinder was in use in the contemporary 14-cylinder Hercules, which was being brought into production when the design of the Centaurus started.[1]

The Centaurus had a cylinder swept volume of 3,272 cu in (53.6 L), nearly as much as the American 3,347.9 cu in (54.9 L) Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone large radial, making the Centaurus one of the largest aircraft piston engines to enter production, while that of the Hercules was 2,363 cu in (38.7 L). The nearly 40 per cent higher capacity was achieved by increasing the stroke from 6.5 to 7 inches (165 to 178 mm) and by changing to two rows of nine cylinders instead of two rows of seven. The diameter of the Centaurus was only just over 6 per cent greater than the Hercules in spite of its much greater swept volume.[2]

The cylinder heads had an indentation like an inverted top hat, which was finned, but it was difficult to get air down into this hollow to adequately cool the head. During development, Bristol contacted ICI Metals Division, Birmingham, to enquire whether a copper-chromium alloy with higher thermal conductivity would have sufficient high temperature strength to be used for this purpose. With the same cylinder volume and using the new material, the horsepower per cylinder was raised from 110 hp (82 kW) to 220 hp (160 kW).

Bristol maintained the Centaurus from type-testing in 1938, but production did not start until 1942, owing to the need to get the Hercules into production and improve the reliability of the entire engine line.[2] Nor was there any real need for the larger engine at this early point in the war, when most military aircraft designs had a requirement for engines of about 1,000 hp (746 kW). The Hercules power of about 1,500 hp (1,119 kW) was better suited to the existing airframes.

The Centaurus did not enter service until near the end of the war, first appearing on the Vickers Warwick. Other wartime, or postwar, uses included the Bristol Brigand and Buckmaster, Hawker Tempest and Sea Fury and the Blackburn Firebrand and Beverley. The engine also entered service after the war in a civilian airliner, the Airspeed Ambassador and was also used in the Bristol Brabazon I Mark 1 prototype aircraft until the Brabazon trans-Atlantic airliner programme was cancelled. The eight Centaurus engines were to be replaced with eight Bristol Proteus gas turbines on the Mark II giving a 100 mph (160 km/h) faster cruising speed at 10,000 ft (3,000 m) higher altitude.[3] By the end of the war in Europe, around 2,500 examples of the Centaurus had been produced by Bristol.[2]

The 373 was the most powerful version of the Centaurus and was intended for the Blackburn Beverley transport aircraft. Using direct fuel injection, it achieved a remarkable 3,220 hp (2,400 kW), but was never fitted.[4] A projected enlarged capacity version of the Centaurus was designed by Sir Roy Fedden; cylinders were produced for this engine, but it was never built. Known as the Bristol Orion, a name used previously for a variant of the Jupiter engine and later re-used for a turboprop, this development was also a two-row, 18 cylinder sleeve valve engine, with the displacement increased to 4,142 cu in (67,875.2 cm3) [6.25 in × 7.5 in (159 mm × 191 mm)], nearly as large as the American Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major four-row, 28-cylinder radial, the largest displacement aviation radial engine ever placed in quantity production.[5]

Variants

editCentaurus I – 2,000 hp (1,500 kW), two-speed full/medium supercharger and left-hand tractor drive. Run on 100 octane fuel.[6]

Centaurus IV – 2,300 hp (1,700 kW), two-speed medium/full supercharger and rigid mounting.[6]

Centaurus V – 2,500 hp (1,900 kW), two-speed full/medium supercharger with cropped impellers. The Centaurus VI was similar to the Centaurus V with master connecting rods in cylinder numbers 7 and 8. The Centaurus VIII was similar to the Centaurus VI with methanol/water fittings.[6]

Centaurus VII – 2,400 hp (1,800 kW), two-speed medium/full supercharger and rigid mounting.[6]

Centaurus IX – 2,500 hp (1,900 kW), and Centaurus XI were similar to the Centaurus VII. The Centaurus X was similar to the Centaurus IX with methanol/water fittings.[7]

Centaurus XII – 2,300 hp (1,700 kW), was a development of the Centaurus IV with twin-turbine entry supercharger, redesigned propeller reduction gear and Hobson-RAE injector and vertically mounted starter motor. The Centaurus XV was a development of the Centaurus VII with flexible mounting.[8]

Centaurus XVIII – 2,470 hp (1,840 kW), was similar to the Centaurus XV.[8]

Centaurus XX – 2,360 hp (1,760 kW), a dual-installation engine for the Bristol Brabazon, similar to the Centaurus 57.[8]

Centaurus 57 – 2,470 hp (1,840 kW), a development of the Centaurus XII with modified supercharger and injector. The Centaurus 58 was a modified Centaurus 57, and the Centaurus 59 was a modified Centaurus 58 with a flexible mounting.[8]

Centaurus 70 – 2,470 hp (1,840 kW), a modified Centaurus 57 with single-speed medium supercharger. The Centaurus 71 was a lightened Centaurus 70 with torquemeter-type reduction gear and 150 hp (110 kW) accessory drive.[9]

Centaurus 100 – 2,470 hp (1,840 kW), a modified Centaurus 57 with two-speed full/medium supercharger and methanol/water injector. The Centaurus 130 was a civil model, modified from the Centaurus 100 with single-speed medium supercharger.[9]

Centaurus 160 – 2,625 hp (1,957 kW), two-speed full/medium supercharger, a front cover suitable for braking propeller, front ignition, 150 hp (110 kW) accessory drive, improved sleeve timing and dynamic suspension mounting. The Centaurus 161 was a Centaurus 160 with torquemeter-type reduction gear. The Centaurus 165 was a Centaurus 161 with improved power section and methanol/water fittings.[9]

Centaurus 170 – 2,625 hp (1,957 kW), a development of the Centaurus 160 with single-speed medium supercharger. The Centaurus 171 was a Centaurus 170 with torquemeter-type reduction gear. The Centaurus 173 was a Centaurus 171 with methanol/water injection and accessory drive. The Centaurus 175 was a Centaurus 173 with modified valve port timings and reduced boost.[9]

Centaurus 373 – 2,370 hp (1,770 kW), a modified Centaurus 173.[9]

Centaurus 568 – 2,470 hp (1,840 kW), a civil engine with two-speed full/medium supercharger modified from the Centaurus 58.[9]

Centaurus 630 – 2,450 hp (1,830 kW), civil engine with single-speed medium supercharger, a front cover suitable for braking propeller, front ignition, 150 hp (110 kW) accessory drive, improved sleeve timing and dynamic suspension mounting. The Centaurus 631 was a Centaurus 630 with torquemeter-type reduction gear.[9]

Centaurus 660 – 2,625 hp (1,957 kW), civil engine with two-speed full/medium supercharger, a front cover suitable for braking propeller, front ignition, 150 hp (110 kW) accessory drive, improved sleeve timing and dynamic suspension mounting. The Centaurus 661 was a Centaurus 660 with torquemeter-type reduction gear. The Centaurus 662 was a Centaurus 660 with methanol/water injection for improved takeoff power, the Centaurus 663 was a Centaurus 662 with torquemeter-type reduction gear.[10]

Applications

editNote:[11]

- Airspeed Ambassador

- Blackburn Beverley

- Blackburn Firebrand

- Blackburn Firecrest

- Breda BZ.308

- Bristol Brabazon

- Bristol Brigand

- Bristol Buckingham

- Bristol Buckmaster

- Fairey Spearfish

- Folland Fo.108 (the Fo.108 was a testbed aircraft for various engines)

- Hawker Fury & Sea Fury

- Hawker Tempest

- Hawker Tornado

- Short Shetland

- Vickers Warwick

Survivors

editThe Royal Navy Historic Flight operated a Hawker Sea Fury powered by a Bristol Centaurus engine[12] until it was destroyed in an accident on 28 April 2021 whilst attempting a forced landing following a failure and seizure of its Bristol Centaurus XVIII engine:

Engines on display

editPreserved Bristol Centaurus engines are on public display at the following museums:

Specifications (Centaurus VII)

editData from British Piston Engines and Their Aircraft[6]

General characteristics

- Type: 18-cylinder, air-cooled, two-row radial engine

- Bore: 5.75 in (146 mm)

- Stroke: 7.00 in (178 mm)

- Displacement: 3,270 cu in (53.6 L)

- Diameter: 55.3 in (1,400 mm)

- Dry weight: 2,695 lb (1,222 kg)

Components

- Valvetrain: Sleeve valve, four ports per sleeve

- Supercharger: Two-speed centrifugal, single stage

- Fuel system: Injection

- Fuel type: 100/130 Octane petrol

- Oil system: Direct-pressure lubrication

- Cooling system: Air-cooled

Performance

- Power output: 2,520 hp (1,880 kW) at 2,700 rpm

- Specific power: 0.77 hp/cu in (35.0 kW/L)

- Compression ratio: 7.2:1

- Power-to-weight ratio: 0.94 hp/lb (1.55 kW/kg)

See also

editRelated development

Comparable engines

- Alfa Romeo 135

- Nakajima Homare

- Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp

- Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone

- Shvetsov ASh-73

Related lists

References

editNotes

edit- ^ Gunston, Bill (1998). Fedden-the life of Sir Roy Fedden. Historical Series No 26. Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust. pp. 175, 179. ISBN 1872922139.

- ^ a b c Bridgman (Jane's) 1998, p. 270.

- ^ Simons, Graham M. (2012). Bristol Brabazon. History Press Limited. p. 100. ISBN 9780752467337.

- ^ "Aero Engines 1956". Flight. 11 May 1956. p. 572. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Gunston 2006, p.152.

- ^ a b c d e Lumsden (1994), p. 125.

- ^ Lumsden (1994), pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b c d Lumsden (1994), p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lumsden (1994), p. 127.

- ^ Lumsden (1994), p. 128.

- ^ List from Lumsden

- ^ Royal Navy Historic Flight - Aircraft Archived 15 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 5 August 2009

Bibliography

edit- Bridgman, L, (ed.) (1998) Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. Crescent. ISBN 0-517-67964-7

- Gunston, Bill. Development of Piston Aero Engines. Cambridge, UK. Patrick Stephens, 2006. ISBN 0-7509-4478-1

- Gunston, Bill. World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines: From the Pioneers to the Present Day. 5th edition, Stroud, UK: Sutton, 2006.ISBN 0-7509-4479-X

- Lumsden, Alec (1994). British Piston Engines and Their Aircraft. Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85310-294-6..

- White, Graham. Allied Aircraft Piston Engines of World War II: History and Development of Frontline Aircraft Piston Engines Produced by Great Britain and the United States During World War II. Warrendale, Pennsylvania: SAE International, 1995. ISBN 1-56091-655-9