The coronation of the monarch of the United Kingdom is an initiation ceremony in which they are formally invested with regalia and crowned at Westminster Abbey. It corresponds to the coronations that formerly took place in other European monarchies, which have all abandoned coronations in favour of inauguration or enthronement ceremonies. A coronation is a symbolic formality and does not signify the official beginning of the monarch's reign; de jure and de facto his or her reign commences from the moment of the preceding monarch's death or abdication, maintaining legal continuity of the monarchy.

The coronation usually takes place several months after the death of the monarch's predecessor, as it is considered a joyous occasion that would be inappropriate while mourning continues. This interval also gives planners enough time to complete the required elaborate arrangements. The most recent coronation took place on 6 May 2023 to crown King Charles III and Queen Camilla.

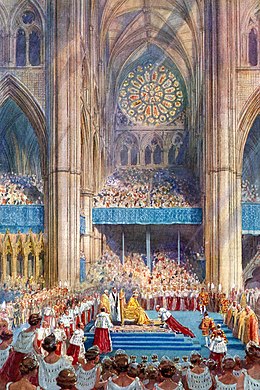

The ceremony is performed by the archbishop of Canterbury, the most senior cleric in the Church of England, of which the monarch is supreme governor. Other clergy and members of the British nobility traditionally have roles as well. Most participants wear ceremonial uniforms or robes, and before the most recent coronation, some wore coronets. Many government officials and guests attend, including representatives of other countries.

The essential elements of the coronation have remained largely unchanged for the past 1,000 years. The sovereign is first presented to, and acclaimed by, the people. The sovereign then swears an oath to uphold the law and the Church. Following that, the monarch is anointed with holy oil, invested with regalia, and crowned, before receiving the homage of their subjects. Consorts of kings are then anointed and crowned as queens. The service ends with a closing procession, and since the 20th century it has been traditional for the royal family to appear later on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to greet crowds and watch a flypast.

History

editEnglish coronations

editEnglish coronations were traditionally held at Westminster Abbey, with the monarch seated on the Coronation Chair. Main elements of the coronation service and the earliest form of oath can be traced to the ceremony devised by Saint Dunstan for King Edgar's coronation in 973 AD at Bath Abbey. It drew on ceremonies used by the kings of the Franks and those used in the ordination of bishops. Two versions of coronation services, known as ordines (from the Latin ordo meaning "order") or recensions, survive from before the Norman Conquest. It is not known if the first recension was ever used in England, and it was the second recension which was used by Edgar in 973 and by subsequent Anglo-Saxon and early Norman kings.[1]

A third recension was probably compiled during the reign of Henry I and was used at the coronation of his successor, Stephen, in 1135. While retaining the most important elements of the Anglo-Saxon rite, it may have borrowed from the consecration of the Holy Roman Emperor from the Pontificale Romano-Germanicum, a book of German liturgy compiled in Mainz in 961, thus bringing the English tradition into line with continental practice.[2] It remained in use until the coronation of Edward II in 1308 when the fourth recension was first used, having been compiled over several preceding decades. Although influenced by its French counterpart, the new ordo focussed on the balance between the monarch and his nobles and on the oath, neither of which concerned the absolutist French kings.[3] One manuscript of this recension is the Liber Regalis at Westminster Abbey which has come to be regarded as the definitive version.[4]

Following the start of the Reformation in England, the boy king Edward VI had been crowned in the first Protestant coronation in 1547, during which Archbishop Thomas Cranmer preached a sermon against idolatry and "the tyranny of the bishops of Rome". However, six years later, he was succeeded by his half-sister Mary I, who restored the Catholic rite.[5] In 1559, Elizabeth I underwent the last English coronation under the auspices of the Catholic Church; however, Elizabeth's insistence on changes to reflect her Protestant beliefs resulted in several bishops refusing to officiate at the service, and it was conducted by the low-ranking bishop of Carlisle, Owen Oglethorpe.[6]

Scottish coronations

editScottish coronations were traditionally held at Scone Abbey in Perthshire, with the monarch seated on the Stone of Destiny. The original rituals were a fusion of ceremonies used by the kings of Dál Riata, based on the inauguration of Aidan by Columba in 574, and by the Picts from whom the Stone of Destiny came. A crown does not seem to have been used until the inauguration of Alexander II in 1214. The ceremony included the laying on of hands by a senior cleric and the recitation of the king's genealogy.[7] The Bishop of St Andrews (from 1472 an archbishop) usually presided, but other bishops and archbishops also performed at some coronations.[8][9]

After the coronation of John Balliol, the Stone was taken to Westminster Abbey in 1296 and in 1300–1301 Edward I of England had it incorporated into the English Coronation Chair.[10] Its first certain use at an English coronation was that of Henry IV in 1399.[11] Pope John XXII in a bull of 1329 granted the kings of Scotland the right to be anointed and crowned.[7] No record exists of the exact form of the medieval rituals, but a later account exists of the coronation of the 17-month-old infant James V at Stirling Castle in 1513. The ceremony was held in a church, since demolished, within the castle walls and was conducted by the Bishop of Glasgow, because the Archbishop of St Andrews had been killed at the Battle of Flodden.[12] It is likely that the child would have been knighted before the start of the ceremony.[13] The coronation itself started with a sermon, followed by the anointing and crowning, then the coronation oath, in this case taken for the child by an unknown noble or priest, and finally an oath of fealty and acclamation by the congregation.[14]

James VI had been crowned in the Church of the Holy Rude at Stirling in 1567. After the Union of the Crowns, he was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 25 July 1603. His son Charles I travelled north for a Scottish coronation at Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh in 1633,[15] but caused consternation amongst the Presbyterian Scots by his insistence on elaborate High Anglican ritual, arousing "gryt feir of inbriginge of poperie".[16] Charles II underwent a simple Presbyterian coronation ceremony at Scone in 1651, but his brother James VII and II was never crowned in Scotland, although Scottish peers attended his 1685 coronation in London, setting a precedent for future ceremonies.[17] The coronation of Charles II was the last to take place in Scotland, and no bishop presided as the episcopacy had been abolished; the de facto head of government, Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, crowned Charles instead.[18]

Modern coronations

editThe Liber Regalis was translated into English for the first time for the coronation of James I in 1603, partly as a result of the reformation in England requiring services to be understood by the people,[19] but also an attempt by antiquarians to recover a lost English identity from before the Norman Conquest.[20] In 1685, James II, who was a Catholic, ordered a truncated version of the service omitting the Eucharist, but this was restored for later monarchs. Only four years later, the service was again revised by Henry Compton for the coronation of William III and Mary II.[21] The Latin text was resurrected for the 1714 coronation of the German-speaking George I, since it was the only common language between the king and the clergy. Perhaps because the 1761 coronation of George III had been beset by "numerous mistakes and stupidities",[22] the next time around, spectacle overshadowed the religious aspect of the service. The coronation of George IV in 1821 was an expensive and lavish affair with a vast amount of money being spent on it.[23]

George's brother and successor William IV had to be persuaded to be crowned at all; his coronation at a time of economic depression in 1831 cost only one sixth of that spent on the previous event. Traditionalists threatened to boycott what they called a "Half Crown-nation".[24] The king merely wore his robes over his uniform as Admiral of the Fleet.[25] For this coronation, a number of economising measures were made which would set a precedent followed by future monarchs. The assembly of peers and ceremonial at Westminster Hall involving the presentation of the regalia to the monarch was eliminated. The procession from Westminster Hall to the Abbey on foot was likewise eliminated and in its place, a state procession by coach from St James's Palace to the abbey was instituted, an important feature of the modern event.[24] The coronation banquet after the service proper was also terminated.[26]

When Victoria was crowned in 1838, the service followed the pared-down precedent set by her uncle, and the under-rehearsed ceremonial, again presided over by William Howley, was marred by mistakes and accidents.[27] The music in the abbey was widely criticised in the press, only one new piece having been written for it, and the large choir and orchestra were badly coordinated.[28]

In the 20th century, liturgical scholars sought to restore the spiritual meaning of the ceremony by rearranging elements with reference to the medieval texts,[29] creating a "complex marriage of innovation and tradition".[30] The greatly increased pageantry of the state processions was intended to emphasise the strength and diversity of the British Empire.[31]

Bringing coronations to the people

editThe idea of the need to gain popular support for a new monarch by making the ceremony a spectacle for ordinary people, started with the coronation in 1377 of Richard II who was a 10-year-old boy, thought unlikely to command respect simply by his physical appearance. On the day before the coronation, the boy king and his retinue were met outside the City of London by the lord mayor, aldermen and the livery companies, and he was conducted to the Tower of London where he spent the night in vigil. The following morning, the king travelled on horseback in a great procession through the decorated city streets to Westminster. Bands played along the route, the public conduits flowed with red and white wine, and an imitation castle had been built in Cheapside, probably to represent the New Jerusalem, where a girl blew gold leaf over the king and offered him wine. Similar, or even more elaborate pageants continued until the coronation of Charles II in 1661.[32] Charles's pageant was watched by Samuel Pepys who wrote: "So glorious was the show with gold and silver that we were not able to look at it". James II abandoned the tradition of the pageant to pay for jewels for his queen[33] and thereafter there was only a short procession on foot from Westminster Hall to the abbey. For the coronation of William IV and Adelaide in 1831, a state procession from St James's Palace to the abbey was instituted, and this pageantry is an important feature of the modern event.[24]

In early modern coronations, the events inside the abbey were usually recorded by artists and published in elaborate folio books of engravings,[34] the last of these was published in 1905 depicting the coronation which had taken place three years earlier.[35] Re-enactments of the ceremony were staged at London and provincial theatres; in 1761, a production featuring the Westminster Abbey choir at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden ran for three months after the real event.[34] In 1902, a request to record the ceremony on a gramophone record was rejected, but Sir Benjamin Stone photographed the procession into the abbey.[35] Nine years later, at the coronation of George V, Stone was allowed to photograph the recognition, the presentation of the swords, and the homage.[36]

The coronation of George VI in 1937 was broadcast on radio by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), and parts of the service were filmed and shown in cinemas.[37] The state procession was shown live on the new BBC Television Service, the first major outside broadcast.[38] At Elizabeth II's coronation in 1953, most of the proceedings inside the abbey were also televised by the BBC. Originally, events as far as the choir screen were to be televised live, with the remainder to be filmed and released later after any mishaps were edited out. This would prevent television viewers from seeing most of the highlights of the coronation, including the actual crowning, live; it led to controversy in the press and even questions in parliament.[39] The organising committee subsequently decided that the entire ceremony would be televised, except for the anointing and communion, which had also been excluded from photography at the last coronation. It was revealed 30 years later that the about-face was due to the personal intervention of the Queen. It is estimated that over 20 million people watched the broadcast in the United Kingdom. The coronation contributed to the increase of public interest in television, which rose significantly.[40]

Commonwealth realms

editThe need to include the various elements of the British Empire in coronations was not considered until 1902, when it was attended by the prime ministers and governors-general of the British Dominions, by then almost completely autonomous, and also by many of the rulers of the Indian Princely States and the various British Protectorates. An Imperial Conference was held afterwards.[41] In 1911, the procession inside Westminster Abbey included the banners of the dominions, India and the Home Nations. By 1937, the Statute of Westminster 1931 had made the dominions fully independent, and the wording of the coronation oath was amended to include their names and confine the elements concerning religion to the United Kingdom.[42]

Thus since 1937, the monarch has been simultaneously crowned as sovereign of several independent nations besides the United Kingdom, known since 1953 as the Commonwealth realms. Elizabeth II was asked, for example: "Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon, and of your Possessions and other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?"[43] In 2023, the oath was amended to avoid reciting the realms other than the United Kingdom during the coronation of Charles III.[44]

Preparations

editTiming

editThe timing of the coronation has varied throughout British history. King Edgar's coronation was some 15 years after his accession in 959 and may have been intended to mark the high point of his reign, or that he reached the age of 30, the age at which Jesus Christ was baptised.[45] Harold II was crowned on the day after the death of his predecessor, Edward the Confessor, the rush probably reflecting the contentious nature of Harold's succession;[46] whereas the first Norman monarch, William I, was also crowned on the day he became king, 25 December 1066,[47] but three weeks since the surrender of English nobles and bishops at Berkhampstead, allowing time to prepare a spectacular ceremony.[46] Most of his successors were crowned within weeks, or even days, of their accession. Edward I was fighting in the Ninth Crusade when he acceded to the throne in 1272; he was crowned soon after his return in 1274.[48] Edward II's coronation, similarly, was delayed by a campaign in Scotland in 1307.[49] Henry VI was only a few months old when he acceded in 1422; he was crowned in 1429, but did not officially assume the reins of government until he was deemed of sufficient age, in 1437.[50] Pre-modern coronations were usually either on a Sunday, the Christian Sabbath, or on a Christian holiday. Edgar's coronation was at Pentecost,[51] William I's on Christmas Day, possibly in imitation of the Byzantine emperors,[52] and John's was on Ascension Day.[53] Elizabeth I consulted her astrologer, John Dee, before deciding on an auspicious date.[54] The coronations of Charles II in 1661 and Anne in 1702 were on St George's Day, the feast of the patron saint of England.[55]

Under the Hanoverian monarchs in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was deemed appropriate to extend the waiting period to several months, following a period of mourning for the previous monarch and to allow time for preparation of the ceremony.[56] In the case of every monarch between George IV and George V, at least one year passed between accession and coronation.[57] Edward VIII was not crowned and his successor George VI was crowned 5 months after his accession. The coronation date of his predecessor had already been set; planning simply continued with a new monarch.[58] The coronation of Charles III and Camilla was held on 6 May 2023, eight months after he acceded to the throne.[59]

Since a period of time has often passed between accession and coronation, some monarchs were never crowned. Edward V and Lady Jane Grey were both deposed before they could be crowned, in 1483 and 1553, respectively.[60] Edward VIII also went uncrowned, as he abdicated in 1936 before the end of the customary one-year period between accession and coronation.[57] A monarch, however, accedes to the throne the moment their predecessor dies, not when they are crowned, hence the traditional proclamation: "The king is dead, long live the king!"[61]

Location

editThe Anglo-Saxon monarchs used various locations for their coronations, including Bath, Kingston upon Thames, London, and Winchester. The last Anglo-Saxon monarch, Harold II, was crowned at Westminster Abbey in 1066; the location was preserved for all future coronations.[62] When London was under the control of rebels,[63] Henry III was crowned at Gloucester in 1216; he later chose to have a second coronation at Westminster in 1220.[64] Two hundred years later, Henry VI also had two coronations; as king of England in London in 1429, and as king of France in Paris in 1431.[50]

Coronation of consorts and others

editCoronations may be performed for a person other than the reigning monarch. In 1170, Henry the Young King, heir apparent to the throne, was crowned as a second king of England, subordinate to his father Henry II;[65] such coronations were common practice in mediaeval France and Germany, but this is only one of two instances of its kind in England (the other being that of Ecgfrith of Mercia in 796, crowned whilst his father, Offa of Mercia, was still alive).[66] More commonly, a king's wife is crowned as queen consort. If the king is already married at the time of his coronation, a joint coronation of both king and queen may be performed.[56] The first such coronation was of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1154; eighteen such coronations have been performed, including that of the co-rulers William III and Mary II.[67] The most recent was that of Charles III and his wife Camilla in 2023. If the king married, or remarried, after his coronation, or if his wife was not crowned with him for some other reason, she might be crowned in a separate ceremony. The first such separate coronation of a queen consort in England was that of Matilda of Flanders in 1068;[68] the last was Anne Boleyn's in 1533.[69] The most recent king to wed post-coronation, Charles II, did not have a separate coronation for his bride, Catherine of Braganza.[70] In some instances, the king's wife was simply unable to join him in the coronation ceremony due to circumstances preventing her from doing so. In 1821, George IV's estranged wife Caroline of Brunswick was not invited to the ceremony; when she showed up at Westminster Abbey anyway, she was denied entry and turned away.[71] Following the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell declined the crown but underwent a coronation in all but name in his second investiture as Lord Protector in 1657.[72]

Participants

editClergy

editThe Archbishop of Canterbury, who has precedence over all other clergy and all laypersons except members of the royal family,[73] traditionally officiates at coronations;[74] in his absence, another bishop appointed by the monarch may take the archbishop's place.[75] There have, however, been several exceptions. William I was crowned by the Archbishop of York, since the Archbishop of Canterbury had been appointed by the Antipope Benedict X, and this appointment was not recognised as valid by the Pope.[76] Edward II was crowned by the Bishop of Winchester because the Archbishop of Canterbury had been exiled by Edward I.[77] Mary I, a Catholic, refused to be crowned by the Protestant Archbishop Thomas Cranmer; the coronation was instead performed by the Bishop of Winchester.[78] Elizabeth I was crowned by the Bishop of Carlisle (to whose see is attached no special precedence) because the senior prelates were "either dead, too old and infirm, unacceptable to the queen, or unwilling to serve".[79] Finally, when James II was deposed and replaced with William III and Mary II jointly, the Archbishop of Canterbury refused to recognise the new sovereigns; he had to be replaced by the Bishop of London, Henry Compton.[80] Hence, in almost all cases where the Archbishop of Canterbury has failed to participate, his place has been taken by a senior cleric: the Archbishop of York is second in precedence, the Bishop of London third, the Bishop of Durham fourth, and the Bishop of Winchester fifth.[73]

Bishops Assistant

editFrom the moment they enter the Abbey until the moment they leave, the monarch is flanked by two supporting bishops of the Church of England.

The part played by two supporting bishops dates back to the coronation of Edgar in 973: two bishops led him by hand into Bath Abbey. Since the coronation of Richard I in 1189, the Bishops of Bath & Wells and Durham have assumed this duty.

Custom has it that they accompany the monarch throughout the ceremony, flanking them as they process from the entrance of Westminster Abbey and standing either side of St Edward’s Chair during the anointing. Bishops Assistant may also carry the Bible, paten, and chalice in the procession.[81]

The Bishop of Durham stands on the monarch's right and the Bishop of Bath and Wells on their left.[82] During the Coronation of King Charles III, Queen Camilla was similarly accompanied by Bishops Assistant – the Bishops of Hereford and of Norwich – on her right and left respectively.[83]

Great Officers of State

editThe Great Officers of State traditionally participate during the ceremony. The offices of Lord High Steward and Lord High Constable have not been regularly filled since the 15th and 16th centuries respectively; they are, however, revived for coronation ceremonies.[84][85] The Lord Great Chamberlain enrobes the sovereign with the ceremonial vestments, with the aid of the Groom of the Robes and the Master (in the case of a king) or Mistress (in the case of a queen) of the Robes.[43]

The Barons of the Cinque Ports also participated in the ceremony. Formerly, the barons were the members of the House of Commons representing the Cinque Ports of Hastings, New Romney, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich. Reforms in the 19th century, however, integrated the Cinque Ports into a regular constituency system applied throughout the nation. At later coronations, barons were specially designated from among the city councillors for the specific purpose of attending coronations. Originally, the barons were charged with bearing a ceremonial canopy over the sovereign during the procession to and from Westminster Abbey. The last time the barons performed such a task was at the coronation of George IV in 1821. The barons did not return for the coronations of William IV (who insisted on a simpler, cheaper ceremonial) and Victoria. At coronations since Victoria's, the barons have attended the ceremony, but they have not carried canopies.[86]

Other claims to attend the coronation

editMany landowners and other persons have honorific "duties" or privileges at the coronation. Such rights have traditionally been determined by a special Court of Claims, over which the Lord High Steward traditionally presided. The first recorded Court of Claims was convened in 1377 for the coronation of Richard II. By the Tudor period, the hereditary post of Lord High Steward had merged with the Crown, and so Henry VIII began the modern tradition of naming a temporary Steward for the coronation only, with separate commissioners to carry out the actual work of the court.[84]

In 1952, for example, the court accepted the claim of the Dean of Westminster to advise the Queen on the proper procedure during the ceremony (for nearly a thousand years he and his predecessor abbots have kept an unpublished Red Book of practices), the claim of the Lord Bishop of Durham and the Lord Bishop of Bath and Wells to walk beside the Queen as she entered and exited the Abbey and to stand on either side of her through the entire coronation ritual, the claim of the Earl of Shrewsbury in his capacity as Lord High Steward of Ireland to carry a white staff. The legal claim of the Scholars of Westminster School to be the first to acclaim the monarch on behalf of the common people was formally disallowed by the court, but in practice their traditional shouts of "Vivat! Vivat Rex!" were still incorporated into the coronation anthem I was glad.[87]

For the 2023 coronation of Charles III and Camilla, a Coronation Claims Office within the Cabinet Office was established instead of the court.[88]

Other participants and guests

editAlong with persons of nobility, the coronation ceremonies are also attended by a wide range of political figures, including the prime minister and all members of the Cabinet of the United Kingdom, all governors-general and prime ministers of the Commonwealth realms, all governors of British Crown Colonies (now British Overseas Territories), as well as the heads of state of dependent nations. Hereditary peers and their spouses are also invited. For Elizabeth II's coronation in 1953, 8,000 guests were squeezed into Westminster Abbey and each person had to make do with a maximum of 18 inches (46 cm) of seating.[89]

Dignitaries and representatives from other nations are also customarily invited.[56] Traditionally, foreign crowned monarchs and consorts did not attend the coronations of others and were instead represented by other royals. In 1953, Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor (formerly Edward VIII), was not invited to the coronation of Elizabeth II, with the reason given that it was contrary to precedent for a sovereign or former sovereign to attend any coronation of another.[90] The coronation of Charles III and Camilla in 2023 broke with that precedent and 16 foreign monarchs attended.[91][92] English and British queens dowager also did not traditionally attend coronations until Queen Mary broke precedent by attending the 1937 coronation of her son, George VI.[93]

Service

editThe general framework of the coronation service is based on the sections contained in the Second Recension used in 973 for King Edgar. Although the service has undergone two major revisions and a translation, and has been modified for each coronation for the following thousand years, the sequence of taking an oath, anointing, investing of regalia, crowning and enthronement found in the Anglo-Saxon text[94] have remained constant.[95] The coronation ceremonies takes place within the framework of Holy Communion.[96]

Recognition and oath

editBefore the entrance of the sovereign, the litany of the saints is sung during the procession of the clergy and other dignitaries. For the entrance of the monarch, an anthem from Psalm 122, I was glad, is sung.[97]

The sovereign enters Westminster Abbey wearing the crimson surcoat and the Robe of State of crimson velvet and takes their seat on a Chair of Estate. Garter Principal King of Arms, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Great Chamberlain, the Lord High Constable and the Earl Marshal go to the east, south, west and north of the coronation theatre.[98] At each side, the archbishop calls for the recognition of the sovereign, with the words:

Sirs, I here present unto you [name], your undoubted King/Queen. Wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service, are you willing to do the same?[43]

After the people acclaim the sovereign at each side, the archbishop administers an oath to the sovereign.[43] Since the Glorious Revolution, the Coronation Oath Act 1688 has required, among other things, that the sovereign "Promise and Sweare to Governe the People of this Kingdome of England and the Dominions thereto belonging according to the Statutes in Parlyament Agreed on and the Laws and Customs of the same".[99] The oath has been modified without statutory authority; for example, at the coronation of Elizabeth II, the exchange between the Queen and the archbishop was as follows:[43]

The Archbishop of Canterbury: Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon, and of your Possessions and other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?

The Queen: I solemnly promise so to do.

The Archbishop of Canterbury: Will you to your power cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your judgments?

The Queen: I will.

The Archbishop of Canterbury: Will you to the utmost of your power maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel? Will you to the utmost of your power maintain in the United Kingdom the Protestant Reformed Religion established by law? Will you maintain and preserve inviolable the settlement of the Church of England, and the doctrine, worship, discipline, and government thereof, as by law established in England? And will you preserve unto the Bishops and Clergy of England, and to the Churches there committed to their charge, all such rights and privileges, as by law do or shall appertain to them or any of them?

The Queen: All this I promise to do. The things which I have here before promised, I will perform, and keep. So help me God.[43]

In addition to the oath, the monarch may take what is known as the Accession Declaration if they have not yet made it. This declaration was first required by the Bill of Rights of 1689 and is required to be taken at either the first meeting of the parliament after a new monarch's accession (i.e. during the State Opening of Parliament) or at their coronation. The monarch additionally swears a separate oath to preserve Presbyterian church government in the Church of Scotland and this oath is taken before the coronation.[75]

Once the taking of the oath concludes, an ecclesiastic presents a Bible to the sovereign, saying "Here is Wisdom; This is the royal Law; These are the lively Oracles of God."[43] The Bible used is a full King James Bible, including the Apocrypha.[100] At Elizabeth II's coronation, the Bible was presented by the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. Once the Bible is presented, the Holy Communion is celebrated, with a special Collect for the coronation, but the service is interrupted after the Nicene Creed. At the coronation of Elizabeth II, the Epistle was 1 Peter 2:13–17, which instructs readers to respect and obey civil government, and the Gospel was Matthew 22:15–22, which contains Jesus's famous instruction to "render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's".[43]

Anointing

editAfter the Communion service is interrupted, the anthem Come, Holy Ghost is recited, as a prelude to the act of anointing. After this anthem, the Archbishop recites a prayer in preparation for the anointing, which is based on the ancient prayer Deus electorum fortitudo also used in the anointing of French kings. After this prayer, the coronation anthem Zadok the Priest (by George Frederick Handel) is sung by the choir; meanwhile, the crimson robe is removed, and the sovereign proceeds to the Coronation Chair for the anointing,[43] which has been set in a prominent position, wearing the anointing gown. In 1953, the chair stood atop a dais of several steps.[101] This mediaeval chair has a cavity in the base into which the Stone of Scone is fitted for the ceremony. Also known as the "Stone of Destiny", it was used for ancient Scottish coronations until brought to England by Edward I. It has been used for every coronation at Westminster Abbey since. Until 1996, the stone was kept with the chair in Westminster Abbey, but it was moved that year to Edinburgh Castle in Scotland, where it is displayed on the proviso that it be returned to Westminster Abbey for use at future coronations.[10] It was announced by the First Minister in 2020 that the Stone will be relocated to Perth City Hall in 2024.[102]

Once seated in this chair, a canopy of golden cloth was in the past held over the monarch's head for the anointing. The duty of acting as canopy-bearers was performed in recent coronations by four Knights of the Garter.[43] This element of the coronation service is considered sacred and is concealed from public gaze;[103] it has never been photographed or televised. The Dean of Westminster pours consecrated oil from an eagle-shaped ampulla into a filigreed spoon with which the Archbishop of Canterbury anoints the sovereign in the form of a cross on the hands, head, and heart.[43] The Coronation Spoon is the only part of the medieval Crown Jewels which survived the Commonwealth of England.[104] While performing the anointing, the Archbishop recites a consecratory formula recalling the anointing of King Solomon by Nathan the prophet and Zadok the priest.[43]

After being anointed, the monarch rises from the Coronation Chair and kneels down at a faldstool placed in front of it. The archbishop then concludes the ceremonies of the anointing by reciting a prayer that is a modified English translation of the ancient Latin prayer Deus, Dei Filius, which dates back to the Anglo-Saxon second recension.[105] Once this prayer is finished, the monarch rises and sits again in the Coronation Chair. At this point in 2023 the screen was removed.[43]

Investing

editThe sovereign is then enrobed in the colobium sindonis (shroud tunic), over which is placed the supertunica.[43]

The Lord Great Chamberlain presents the spurs,[43] which represent chivalry.[104] The Archbishop of Canterbury, assisted by other bishops, then presents the Sword of State to the sovereign, who places it on the altar. The sovereign is then further robed, this time receiving bracelets and putting the Robe Royal and Stole Royal on top of the supertunica. The Archbishop then delivers several Crown Jewels to the sovereign. First, he delivers the Orb,[43] a hollow gold sphere decorated with precious and semi-precious stones. The Orb is surmounted by a cross, representing the dominion of the divine over the world;[106] it is returned to the altar immediately after being received.[43] Next, the sovereign receives a ring representing their "marriage" to their territories, their subjects, and the divine.[107] The Sovereign's Sceptre with Dove, so called because it is surmounted by a dove representing the Holy Ghost, and the Sovereign's Sceptre with Cross, which incorporates Cullinan I, are delivered to the sovereign.[108]

Crowning

editThe Archbishop of Canterbury lifts St Edward's Crown from the high altar, sets it back down, and says a prayer: "Oh God, the crown of the faithful; bless we beseech thee and sanctify this thy servant our king/queen, and as thou dost this day set a crown of pure gold upon his/her head, so enrich his/her royal heart with thine abundant grace, and crown him/her with all princely virtues through the King Eternal Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen". This prayer is the translation of the ancient formula Deus tuorum Corona fidelium, which first appeared in the twelfth-century third recension.[109]

The Dean of Westminster picks up the crown and he, the archbishop and several other high-ranking bishops proceed to the Coronation Chair where the crown is handed back to the archbishop, who reverently places it on the monarch's head.[110] At this moment, the king or queen is crowned, and the guests in the abbey cry in unison three times, "God Save the King/Queen". The trumpeters sound a fanfare and church bells ring out across the kingdom, as gun salutes echo from the Tower of London and Hyde Park.[111]

Finally, the archbishop, standing before the monarch, says the crowning formula, which is a translation of the ancient Latin prayer Coronet te Deus: "God crown you with a crown of glory and righteousness, that having a right faith and manifold fruit of good works, you may obtain the crown of an everlasting kingdom by the gift of him whose kingdom endureth for ever." To this the guests, with heads bowed, say "Amen".[112]

When this prayer is finished, the choir sings an English translation of the traditional Latin antiphon Confortare: "Be strong and of a good courage; keep the commandments of the Lord thy God, and walk in his ways". During the singing of this antiphon, all stand in their places, and the monarch remains seated in the Coronation Chair still wearing the crown and holding the sceptres. The recitation of this antiphon is followed by a rite of benediction consisting of several prayers, after each one the congregation replies with "a loud and hearty Amen".[43]

Enthronement and homage

editThe benediction being concluded, the sovereign rises from the Coronation Chair and is borne into a throne. Once the monarch is seated on the throne, the formula Stand firm, and hold fast from henceforth... is recited;[43] a translation of the Latin formula Sta et retine..., which was first used in England in the tenth-century second recension, and also appeared in French, German and imperial coronation texts.[113]

After the enthronement proper, the act of homage takes place: the archbishops and bishops swear their fealty, saying "I, N., Archbishop [Bishop] of N., will be faithful and true, and faith and truth will bear unto you, our Sovereign Lord [Lady], King [Queen] of this Realm and Defender of the Faith, and unto your heirs and successors according to law. So help me God." In the past peers then proceeded to pay their homage, saying "I, N., Duke [Marquess, Earl, Viscount, Baron or Lord] of N., do become your liege man of life and limb, and of earthly worship; and faith and truth will I bear unto you, to live and die, against all manner of folks. So help me God."[43] The clergy pay homage together, led by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Next, members of the royal family pay homage individually. The peers were then led by the premier peers of their rank: the dukes by the premier duke, the marquesses by the premier marquess, and so forth.[43] In the shortened coronation of Charles III and Camilla, the paying of homage by the peerage was omitted.[114]

If there is a queen consort, she is anointed, invested, crowned and enthroned in a simple ceremony immediately after homage is paid. The Communion service interrupted earlier is resumed and completed, but with special prayers: there are prayers for the monarch and consort at the Offertory and a special preface.[56][43] Finally, the monarch and consort receive Communion, the Gloria in excelsis Deo is sung and the blessing is given.[115]

Closing procession

editThe sovereign then exits the coronation theatre, entering St Edward's Chapel (within the abbey), preceded by the bearers of the Sword of State, the Sword of Spiritual Justice, the Sword of Temporal Justice and the blunt Sword of Mercy.[116] While the monarch is in St. Edward's chapel, the choir recites an English translation of the hymn of thanksgiving Te Deum laudamus. St Edward's Crown and all the other regalia are laid on the High Altar of the chapel;[43] the sovereign removes the Robe Royal and Stole Royal, exchanges the crimson surcoat for the purple surcoat[117] and is enrobed in the Imperial Robe of purple velvet. The sovereign then dons the Imperial State Crown and takes into their hands the Sceptre with the Cross and the Orb and leaves the chapel first while all present sing the national anthem.[43]

Music

editThe music played at coronations has been primarily classical and religiously inspired. Much of the choral music uses texts from the Bible which have been used at coronations since King Edgar's coronation at Bath in 973 and are known as coronation anthems. In the coronations following the Reformation, court musicians, often the Master of the King's Music, were commissioned to compose new settings for the traditional texts. The most frequently used piece is Zadok the Priest by George Frideric Handel; one of four anthems commissioned from him for George II's coronation in 1727. It has featured in every coronation since, an achievement unparalleled by any other piece. Previous settings of the same text were composed by Henry Lawes for the 1661 coronation of Charles II and Thomas Tomkins for Charles I in 1621.[118]

In the 19th century, works by major European composers were often used, but when Sir Frederick Bridge was appointed director of music for the 1902 coronation of Edward VII, he decided that it ought to be a celebration of four hundred years of British music. Compositions by Thomas Tallis, Orlando Gibbons and Henry Purcell were included alongside works by contemporary composers such as Arthur Sullivan, Charles Villiers Stanford and John Stainer.[119] Hubert Parry's I was glad was written as the entrance anthem for the 1902 coronation, replacing an 1831 setting by Thomas Attwood; it contains a bridge section partway through so that the scholars of Westminster School can exercise their right to be the first commoners to acclaim the sovereign, shouting their traditional "vivats" as the sovereign enters the coronation theatre. This anthem and Charles Villiers Stanford's Gloria in excelsis (1911) have also been used regularly in recent coronations, as has the national anthem, God Save the King (or Queen).[120] Other composers whose music featured in Elizabeth II's coronation include Sir George Dyson, Gordon Jacob, Sir William Henry Harris, Herbert Howells, Sir William Walton, Samuel Sebastian Wesley, Ralph Vaughan Williams and the Canadian-resident but English-born Healey Willan.[121] Ralph Vaughan Williams suggested that a congregational hymn be included. This was approved by the Queen and the Archbishop of Canterbury, so Vaughan Williams recast his 1928 arrangement of Old 100th, the English metrical version of Psalm 100, the Jubilate Deo ("All people that on earth do dwell") for congregation, organ and orchestra: the setting has become ubiquitous at festal occasions in the Anglophone world.[122]

Dress

editSeveral participants in the ceremony wear special costumes, uniforms or robes. For those in attendance (other than members of the royal family) what to wear is laid down in detail by the Earl Marshal prior to each Coronation and published in The London Gazette.[citation needed]

Sovereign's robes

editThe sovereign wears a variety of robes and other garments during the course of the ceremony. In contrast to the history and tradition which surround the regalia, it is customary for most coronation robes to be newly made for each monarch. (The present exceptions are the supertunica and Robe Royal, which both date from the coronation of George IV in 1821.)[124]

Worn for the first part of the service (and the processions beforehand):

- Crimson surcoat – the regular dress during most of the ceremony, worn under all other robes. In 1953, Elizabeth II wore a newly made gown in place of a surcoat.[117]

- Robe of State of crimson velvet or Parliament Robe – the first robe used at a coronation, worn on entry to the abbey and later at State Openings of Parliament. It consists of an ermine cape and a long crimson velvet train lined with further ermine and decorated with gold lace.[117]

Worn over the surcoat for the Anointing:

- Anointing gown – a simple and austere garment worn during the anointing. It is plain white, bears no decoration and fastens at the back.[117]

Robes with which the Sovereign is invested (worn thereafter until Communion):

- Colobium sindonis ("shroud tunic") – the first robe with which the sovereign is invested. It is a loose white undergarment of fine linen cloth edged with a lace border, open at the sides, sleeveless and cut low at the neck. It symbolises the derivation of royal authority from the people.[117]

- Supertunica – the second robe with which the sovereign is invested. It is a long coat of gold silk which reaches to the ankles and has wide-flowing sleeves. It is lined with rose-coloured silk, trimmed with gold lace, woven with national symbols and fastened by a sword belt. It derives from the full dress uniform of a consul of the Byzantine Empire.[117]

- Robe Royal or Pallium Regale – the main robe worn during the ceremony and used during the crowning.[43] It is a four-square mantle, lined in crimson silk and decorated with silver coronets, national symbols and silver imperial eagles in the four corners. It is lay, rather than liturgical, in nature.[117]

- Stole Royal or armilla – a gold silk stole or scarf which accompanies the Robe Royal, richly and heavily embroidered with gold and silver thread, set with jewels and lined with rose-coloured silk and gold fringing.[117]

Worn for the final part of the service (and the processions which follow):

- Purple surcoat – the counterpart to the crimson surcoat, worn during the final part of the ceremony.[117]

- Imperial Robe of purple velvet – the robe worn at the conclusion of the ceremony, on exit from the abbey. It comprises an embroidered ermine cape with a train of purple silk velvet, trimmed with Canadian ermine and fully lined with pure silk English satin. The purple recalls the imperial robes of Roman Emperors.[117]

Headwear

editMale sovereigns up to and including George VI have traditionally worn a crimson cap of maintenance for the opening procession and when seated in the Chair of Estate during the first part of the service. Charles III arrived at his coronation bareheaded in 2023, rather than with the cap. Female sovereigns (and some female consorts) have traditionally worn the George IV State Diadem, first worn by its namesake, George IV. For the Anointing, the sovereign is bareheaded, and remains so until the Crowning. Monarchs are usually crowned with St Edward's Crown but some have chosen to use other crowns as it weighs 2.23 kg (4.9 lb). For the final part of the service, and the processions that follow, it is exchanged for the lighter Imperial State Crown.[125]

Other members of the royal family

editCertain other members of the royal family wear distinctive robes, most particularly queens consort (including dowagers) and princesses of the United Kingdom, all of whom wear purple velvet mantles edged with ermine over their court dresses. Other members of the royal family in attendance dress according to the conventions listed below, except that royal dukes wear a distinctive form of peer's robe, which has six rows of ermine on the cape and additional ermine on miniver edging to the front of the robe.[citation needed]

Headwear

editQueens consort in the 20th century arrived at their coronation bareheaded, and remained so until the point in the service when they were crowned with their own crown. In the late 17th century and 18th century, queens consort wore Mary of Modena's State Diadem.[126] Prior to the 20th century it was not usual for dowager queens to attend coronations, but Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother both attended the coronations of George VI and Elizabeth II respectively, and each wore the crown, minus its arches, with which she had been crowned for the duration of the service.[127][128]

Traditionally, princesses and princes of the United Kingdom were provided with distinctive forms of coronet, which they wore during the service. A male heir-apparent's coronet displays four crosses-pattée alternating with four fleurs-de-lis, surmounted by an arch. The same style, without the arch, is used by other children and siblings of the monarch. The coronets of children of the heir-apparent display four fleurs-de-lis, two crosses-pattée and two strawberry leaves. A fourth style, including four crosses-pattée and four strawberry leaves, is used for the children of the sons and brothers of sovereigns. The tradition of coronets was abolished for the 2023 coronation, and members of the royal family dressed in robes of one of their orders of chivalry.[129]

Peers

editAll peers and peeresses in attendance are "expected to wear" Robes of State, as described below.[130] These robes are different to the Parliament Robe (worn on occasion by peers who are members of the House of Lords); all peers summoned to attend wear the Robe of State, regardless of membership of the House of Lords, and peeresses' robes are worn not only by women who are peers in their own right, but also by wives and widows of peers.[131][132] Those entitled to a collar of an order of knighthood wear it over (and attached to) the cape.[citation needed]

Peers' robes

editA peer's coronation robe is a full-length cloak-type garment of crimson velvet, edged down the front with miniver pure, with a full cape (also of miniver pure) attached. On the cape, rows of "ermine tails (or the like)"[130] indicate the peer's rank: dukes have four rows, marquesses three and a half, earls three, viscounts two and a half, and barons and lords of parliament two.[citation needed]

Prior to the 19th century peers also wore a matching crimson surcoat edged in miniver.

In 1953, "Peers taking part in the Processions or Ceremonies in Westminster Abbey" were directed to wear the Robe of State over full-dress uniform (Naval, Military, RAF or civil), if so entitled, or else over full velvet court dress (or one of the alternative styles of Court Dress, as laid down in the Lord Chamberlain's regulations). Other peers in attendance were "expected to wear the same if possible"; but the wearing of evening dress, or a black suit with white bow tie, were also permitted (as was the use of a Parliament Robe or a mantle of one of the Orders of Knighthood by those not taking part in the Processions or Ceremonies).[130]

Peeresses' robes

editA peeress's coronation robe is described as a long (trained) crimson velvet mantle, edged all round with miniver pure and having a cape of miniver pure (with rows of ermine indicating the rank of the wearer, as for peers).[133] Furthermore, the length of the train (and the width of the miniver edging) varies with the rank of the wearer: for duchesses, the trains are 1.8 m (2 yds) long, for marchionesses one and three-quarters yards, for countesses one and a half yards, for viscountesses one and a quarter yards, and for baronesses and ladies 90 cm (1 yd). The edgings are 13 cm (5 in) in width for duchesses, 10 cm (4 in) for marchionesses, 7.5 cm (3 in) for countesses and 5 cm (2 in) for viscountesses, baronesses and ladies.[citation needed]

This Robe of State is directed to be worn with a sleeved crimson velvet kirtle, which is similarly edged with miniver and worn over a full-length white or cream court dress (without a train).[citation needed]

Headwear

editDuring the Coronation, peers and peeresses formerly put on coronets. Like their robes, their coronets are differentiated according to rank: the coronet of a duke or duchess is ornamented with eight strawberry leaves, that of a marquess or marchioness has four strawberry leaves alternating with four raised silver balls, that of an earl or countess eight strawberry leaves alternating with eight raised silver balls, that of a viscount or viscountess has sixteen smaller silver balls and that of a baron or baroness six silver balls. Peeresses' coronets are identical to those of peers, but smaller.[134] In addition, peeresses were told in 1953 that "a tiara should be worn, if possible".[130] The use of coronets was abolished for the 2023 coronation.

Others

editIn 1953, those taking part in the Procession inside the Abbey who were not peers or peeresses were directed to wear full-dress (naval, military, air force or civil) uniform, or one of the forms of court dress laid down in the Lord Chamberlain's Regulations for Dress at Court. These regulations, as well as providing guidance for members of the public, specify forms of dress for a wide variety of office-holders and public officials, clergy, the judiciary, members of the Royal Household, etc. It also includes provision for Scottish dress to be worn.[135]

Officers in the Armed Forces and the Civil, Foreign, and Colonial Services who did not take part in the Procession wore uniform, and male civilians: "one of the forms of court dress as laid down in the Lord Chamberlain's Regulations for Dress at Court, or evening dress with knee breeches or trousers, or morning dress, or dark lounge suits".[133]

Ladies attending in 1953 were instructed to wear "evening dresses or afternoon dresses, with a light veiling falling from the back of the head". Coats and hats were not permitted but tiaras could be worn.[citation needed]

In 1953 an additional note made it clear that "Oriental dress may be worn by Ladies and Gentlemen for whom it is the usual Ceremonial Costume".[133]

After-celebrations

editSince the 20th century it has been traditional for the newly crowned monarch and other members of the royal family to sit for official portraits at Buckingham Palace and appear on the balcony, from where in 1953 they watched a flypast by the Royal Air Force.[136] During the appearance, the monarch wears the Imperial State Crown and, if there is one, the queen consort wears her consort crown. In the evening, a fireworks display is held nearby, usually in Hyde Park.[137] In 1902, Edward VII's illness led to the postponement of a fourteen-course banquet at Buckingham Palace.[138] In 1953, two state banquets were held in the ballroom there, and classical music was provided by the Royal Horse Guards.[139]

Historically, the coronation was immediately followed by a banquet held in Westminster Hall in the Palace of Westminster (which is also the home to the Houses of Parliament). The King or Queen's Champion (the office being held by the Dymoke family in connection with the Manor of Scrivelsby) would ride into the hall on horseback, wearing a knight's armour, with the Lord High Constable riding to his right and the Earl Marshal riding to his left. A herald would then make a proclamation of the readiness of the champion to fight anyone denying the monarch. After 1800, the form for this was as follows:[140]

If any person, of what degree soever, high or low, shall deny or gainsay our Sovereign Lord ..., King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, son and next heir unto our Sovereign Lord the last King deceased, to be the right heir to the Imperial Crown of this Realm of Great Britain and Ireland, or that he ought not to enjoy the same; here is his Champion, who saith that he lieth, and is a false traitor, being ready in person to combat with him; and in this quarrel will adventure his life against him, on what day soever he shall be appointed.[140]

The King's Champion would then throw down the gauntlet; the ceremony would be repeated at the centre of the hall and at the High Table (where the sovereign would be seated). The sovereign would then drink to the champion from a gold cup, which he would then present to the latter.[140] This ritual was dropped from the coronation of Queen Victoria and was never revived. The offices of Chief Butler of England, Grand Carver of England and Master Carver of Scotland were also associated with the coronation banquet.[141]

Banquets have not been held at Westminster Hall since the coronation of George IV in 1821. His coronation was the most elaborate in history; his brother and successor William IV eliminated the banquet on grounds of economy,[26] ending a 632-year-old tradition.[142] Since 1901, a Coronation Fleet Review has also been held. To celebrate the coronation, a coronation honours list is also released before the coronation.[citation needed]

Enthronement as Emperor of India

editQueen Victoria assumed the title Empress of India in 1876.[143] A durbar (court) was held in Delhi, India on 1 January 1877 to proclaim her assumption of the title. The queen did not attend personally, but she was represented there by the Viceroy, Lord Lytton.[144] A similar durbar was held on 1 January 1903 to celebrate the accession of Edward VII, who was represented by his brother the Duke of Connaught.[145] In 1911, George V also held a durbar which he and his wife Queen Mary attended in person. Since it was deemed inappropriate for a Christian anointing and coronation to take place in a largely non-Christian nation, George V was not crowned in India; instead, he wore an imperial crown as he entered the Durbar. Tradition prohibited the removal of the Crown Jewels from the United Kingdom; therefore, a separate crown, known as the Imperial Crown of India, was created for him. The emperor was enthroned, and the Indian princes paid homage to him. Thereafter, certain political decisions, such as the decision to move the capital from Calcutta to Delhi, were announced at the durbar. The ceremony was not repeated, and the imperial title was abandoned by George VI in 1948, 10 months after India gained independence.[146]

Kings of Arms

editAside from kings and queens, the only individuals authorised to wear crowns (as opposed to coronets) are the Kings of Arms, the United Kingdom's senior heraldic officials.[147] Like the peers' coronets, these crowns are only put on at the actual moment of the monarch's crowning, after which they are worn for the rest of the service and its subsequent festivities. Garter, Clarenceaux, and Norroy and Ulster Kings of Arms have heraldic jurisdiction over England, Wales and Northern Ireland;[148] Lord Lyon King of Arms is responsible for Scotland.[149] In addition, there is a King of Arms attached to each of the Order of the Bath, Order of St. Michael and St. George and the Order of the British Empire. These have only a ceremonial role, but are authorised by the statutes of their orders to wear the same crown as Garter at a coronation.[150] The crown of a King of Arms is silver-gilt and consists of sixteen acanthus leaves alternating in height, and inscribed with the words Miserere mei Deus secundum magnam misericordiam tuam (Latin: "Have mercy on me O God according to Thy great mercy", from Psalm 51).[147] The Lord Lyon King of Arms has worn a crown of this style at all coronations since that of George III. Prior to that he wore a replica of the Crown of Scotland. In 2004 a new replica of this crown was created for use by the Lord Lyon.[151]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Gosling, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Strong, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Strong, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Strong, p. 84.

- ^ Strong, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Strong, p. 208.

- ^ a b Thomas, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Lyall, Roderick J. (1977). "The Medieval Scottish Coronation Service: Some Seventeenth-Century Evidence". The Innes Review. 28: 3–21. doi:10.3366/inr.1977.28.1.3.

- ^ Barrow, G. W. S. (1997). "Observations on the Coronation Stone of Scotland". The Scottish Historical Review. 76 (201): 115–121. doi:10.3366/shr.1997.76.1.115. JSTOR 25530742 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b "The Coronation Chair". Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Strong, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Thomas, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Thomas, p. 53.

- ^ Thomas, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Range, p. 43.

- ^ Strong, p. 257.

- ^ Strong, p. 351.

- ^ "Biography of Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquis of Argyll". bcw-project.org.

- ^ Gosling, p. 10.

- ^ Strong, p. 244

- ^ The Coronation Service of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. HMSO. 1953. pp. 14–17. ISBN 9781001288239.

- ^ Gosling pp. 54–55

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher. "George IV (1762–1830)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10541. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c Strong, p. 401.

- ^ Carpenter, Edward; Gentleman, David (1987). Westminster Abbey. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 89. ISBN 0-297-79085-4.

- ^ a b Strong, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Gosling p. 52

- ^ Range, p. 224

- ^ Strong, p. 470.

- ^ Strong, p. 480.

- ^ Richards, p. 101

- ^ Strong, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Gosling p. 33

- ^ a b Strong, p. 415.

- ^ a b Strong, p. 432.

- ^ Strong, p. 433.

- ^ Rose, p. 121.

- ^ "The story of BBC Television – Television out and about". History of the BBC. BBC. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ The Times (London). 29 October 1952. p. 4.

- ^ Strong, pp. 433–435.

- ^ Strong, p. 437.

- ^ Strong, pp. 442–444.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Simon Kershaw (2002). "The Form and Order of Service that is to be performed and the Ceremonies that are to be observed in The Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in the Abbey Church of St. Peter, Westminster, on Tuesday, the second day of June, 1953". Oremus. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ "Coronation order of service in full". BBC. 6 May 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ Strong, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Strong, p. 38.

- ^ David Bates (2004). "William I (1027/8–1087)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29448.

- ^ Michael Prestwick (2004). "Edward I (1239–1307)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8517.

- ^ J.R.S. Phillips (2004). "Edward II (1284–1327)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8518.

- ^ a b R.A. Griffiths (2004). "Henry VI (1421–1471)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12953.

- ^ Gosling, p. 5.

- ^ Strong, p. 36.

- ^ Strong, p. 43.

- ^ Strong, p. 212.

- ^ Roger A. Mason (2006). Scots and Britons: Scottish Political Thought and the Union of 1603. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-521-02620-8.

- ^ a b c d Royal Household (21 December 2015). "Coronation". Royal family website. Archived from the original on 5 February 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Monarchs of Great Britain and the United Kingdom (1707–2003)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/92648. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2007.(subscription required)

- ^ H.C.G. Matthew (2004). "George VI (1895–1952)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33370.

- ^ "Coronation on 6 May for King Charles and Camilla, Queen Consort". BBC News. 11 October 2022. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ "Monarchs of England (924–1707)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/92701. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2007.(subscription required)

- ^ Royal Household. "Accession". British Monarchy website. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015.

- ^ "England: Anglo-Saxon Consecrations: 871–1066". Archontology. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Strong, p. 72.

- ^ H.W. Ridgeway (2004). "Henry III (1207–1272)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12950.

- ^ Thomas K. Keefe (2004). "Henry II (1133–1189)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12949.

- ^ J.J. Spigelman (8 October 2002). "Becket and Henry II: Exile". Fourth Address in the Becket Lecture Series to the St Thomas More Society, Sydney. Sydney: Supreme Court of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 26 November 2007.

- ^ Strong, pp. 30–31. Note: The dates of the coronations of three queens are unknown.

- ^ Elisabeth van Houts (2004). "Matilda (d. 1083)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18335.

- ^ Strong, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Woolley, p. 199.

- ^ Smith, E. A. "Caroline (1768–1821)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4722. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ John Morrill (2004). "Cromwell, Oliver (1599–1658)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6765.

- ^ a b François Velde. "Order of Precedence in England and Wales". Heraldica. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ The Royal Household (25 May 2003). "50 facts about the Queen's coronation". British Monarchy website. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012.

- ^ a b Lucinda Maer; Oonagh Gay (27 August 2008). "The coronation oath". House of Commons Library. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Hilliam, p. 16.

- ^ Hilliam, p. 48.

- ^ Strong, p. 205.

- ^ Patrick Collinson, "Elizabeth I (1533–1603)" Archived 19 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, January 2012, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8636 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Strong, p. 337.

- ^ Church Times, "Coronation bishops confirmed for ceremonial roles", 14 April 2023 Retrieved 19 June 2023

- ^ The Northern Echo, "The Bishop of Durham's intimate role in the coronation ceremony," 6th May 2023 Retrieved 19 June 2023

- ^ see the photographs in Express and Star, "Former Bishop of Dudley accompanies Queen during coronation" Retrieved 19 June 2023

- ^ a b Vernon-Harcourt, Leveson William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 3.

- ^ "Coronation of George IV: Barons of the Cinque Ports". The Royal Pavilion, Libraries and Museums Collections. Brighton and Hove Museums. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009.

- ^ Coronation of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth the Second: Minutes of the Proceedings of the Court of Claims, 1952. Crown Office. 1952.

- ^ "Coronation Claims Office to Look at Historic and Ceremonial Roles for King Charles III's Coronation". gov.uk (Press release). Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "Pictures of the Coronation". Government Art Collection. Department for Culture, Media & Sport. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "The King Who Did Not Attend the Coronation". Vanity Fair. 3 May 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "King Charles' Coronation Guest List Just Added Foreign Royals – Including a Break From Tradition". Peoplemag. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "The King's Coronation guest list: a who's who of every foreign royal attending". Tatler. 27 February 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "Queen to Set Precedent By Seeing Son Crowned". The New York Times. 18 January 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Strong, 28–29

- ^ Gosling, p. 5

- ^ "Guide to the Coronation Service" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ Strong p. 488

- ^ Strong p. 258

- ^ "Coronation Oath Act 1688: Section III. Form of Oath and Administration thereof". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ P.J. Carefoote (June 2006). "The Coronation Bible" (PDF). The Halcyon: The Newsletter of the Friends of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (37). University of Toronto. ISSN 0840-5565. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Coronation of the British Monarch". Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2007., Image of 'Completed Coronation Theatre' at bottom.

- ^ "The Stone of Destiny - gov.scot". Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "The coronation: An intimate ritual" (PDF). The Anglican Communion. 2 June 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2005. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ^ a b Royal Household (15 January 2016). "The Crown Jewels". Royal family website. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Legg p. xxxix

- ^ Hilliam, p. 209.

- ^ Hilliam, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Hilliam, p. 210.

- ^ Legg p. xlvi

- ^ Sir George Younghusband; Cyril Davenport (1919). The Crown Jewels of England. Cassell & Co. p. 78. ASIN B00086FM86.

- ^ Gosling p. 40

- ^ Sir Thomas Butler (1989). The Crown Jewels and Coronation Ceremony. Pitkin. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-85372-467-4.

- ^ Jackson, Richard A., ed. (1995). Ordines Coronationis Franciae: Volume I. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0812232639. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "The Authorised Liturgy for the Coronation Rite of His Majesty King Charles III" (PDF). Church of England. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Gosling p. 42

- ^ Hilliam, pp. 211–212.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cox, N. (1999). "The Coronation Robes of the Sovereign". Arma. 5 (1): 271–280.

- ^ Range, p. 282.

- ^ Jeffrey Richards (2001). Imperialism and Music: Britain, 1876–1953. Manchester University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-7190-6143-1.

- ^ Anselm Hughes (1953). "Music of the Coronation over a Thousand Years". Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association. 79. Taylor & Francis: 81–100. JSTOR 766213.

- ^ "Coronation music". Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Music for the Coronation". The Musical Times. 94 (1325): 305–307. July 1953. doi:10.2307/933633. JSTOR 933633.

- ^ Arnold Wright; Philip Smith (1902). Parliament Past and Present. London: Hutchinson. p. 190.

- ^ Rose, p. 100.

- ^ Gosling 2013, pp. 25-26

- ^ "Mary of Modena's Diadem 1685". rct.uk. The Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Queen Mary's Crown 1911". rct.uk. The Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother's Crown 1937". rct.uk. The Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Ward, Victoria (3 May 2023). "Peers to wear coronation robes in last minute Palace U-turn". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d "No. 39709". The London Gazette. 2 December 1952. p. 6351.

- ^ a b Cox, N. (1999). "The Coronation and Parliamentary Robes of the British Peerage". Arma. 5 (1): 289–293.

- ^ Peers have two types of robes, the "Parliamentary Robe" and the "Coronation Robe". The Coronation Robe is worn only during a coronation while the Parliamentary Robe is worn on other formal occasions such as the State Opening of Parliament.[131] See also: Privilege of peerage#Robe

- ^ a b c "No. 39709". The London Gazette. 2 December 1952. p. 6352.

- ^ Cox, N. (1999). "The Coronets of Members of the Royal Family and of the Peerage". The Double Tressure. 22: 8–13.

- ^ "Dress and insignia worn at His Majesty's court, issued with the authority of the lord chamberlain". London, Harrison & sons, ltd. 7 May 1921 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Coronation at Buckingham Palace: the Coronation Procession". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ Rose, p. 129.

- ^ John Burnett (2013). Plenty and Want: A Social History of Food in England from 1815 to the Present Day. Routledge. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-136-09084-4.

- ^ "The Coronation State Banquets at Buckingham Palace". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Fallow, Thomas Macall (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 07 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 185–187.

- ^ Alistair Bruce; Julian Calder; Mark Cator (2000). Keepers of the Kingdom: the Ancient Offices of Britain. London: Seven Dials. p. 29. ISBN 1-84188-073-6.

- ^ "Coronation banquets". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "No. 24319". The London Gazette. 28 April 1876. p. 2667.

- ^ The Times (London). 2 January 1877. p. 5.

- ^ The Times (London). 2 January 1903. p. 3.

- ^ Hilliam, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b "King of Arms". Chambers's Encyclopædia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge for the People. Edinburgh: W & R Chambers. 1863. pp. 796–7.

- ^ "The origin and history of the various heraldic offices". About the College of Arms. College of Arms. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010.

- ^ "History of the Court of the Lord Lyon". Archived from the original on 2 August 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ See e.g. (Order of the Bath), "No. 20737". The London Gazette. 25 May 1847. p. 1956. (Order of the British Empire) "No. 32781". The London Gazette. 29 December 1922. p. 9160.

- ^ "Lord Lyon gets his crown back". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 13 July 2003. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

Bibliography

edit- Gosling, Lucinda (2013). Royal Coronations. Oxford: Shire. ISBN 978-0-74781-220-3.

- Hilliam, David (2001). Crown, Orb & Sceptre: The True Stories of English Coronations. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 978-0-75-092538-9.

- Le Hardy, William (1937). The Coronation Book: the History and Meaning of the Ceremonies at the Crowning of the King and Queen. London: Hardy & Reckitt.

- Legg, Leopold George Wickham, ed. (1901). English Coronation Records. Westminster: A. Constable & Company, Limited.

- Range, Matthias (2012). Music and Ceremonial at British Coronations: From James I to Elizabeth II. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02344-4.

- Richards, Jeffrey (2001). Imperialism and Music: Britain, 1876-1953. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6143-1.

- Rose, Tessa (1992). The Coronation Ceremony of the Kings and Queens of England and the Crown Jewels. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-701361-2.

- Strong, Sir Roy (2005). Coronation: A History of Kingship and the British Monarchy. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-716054-9.

- Thomas, Andrea (2008). "Coronation Ritual and Regalia". In Goodare, Julian; MacDonald, Alasdair A. (eds.). Sixteenth-Century Scotland: Essays in Honour of Michael Lynch. Netherlands: Brill. pp. 43–68. ISBN 978-90-04-16825-1.

- Woolley, Reginald Maxwell (1915). Coronation Rites. London: Cambridge University Press.

External links

edit- Coronations and the Royal Archives at the Royal Family website

- Coronations: An ancient ceremony at the Royal Collection Trust website

- A Synopsis of English and British Coronations

- Planning the next Accession and Coronation: FAQs by The Constitution Unit, University College London

- Book describing English medieval Coronation found in Pamplona at the Medieval History of Navarre website (in Spanish)

Videos

edit- Elizabeth is Queen (1953) 47-minute documentary by British Pathé at YouTube

- Coronation 1937 – Technicolor – Sound newsreel by British Movietone News at YouTube

- Long to Reign Over Us, Chapter Three: The Coronation by Lord Wakehurst on the Royal Channel at YouTube