This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Bronze Age of Comic Books is an informal name for a period in the history of American superhero comic books, usually said to run from 1970 to 1985.[1] It follows the Silver Age of Comic Books and is followed by the Modern Age of Comic Books.

| Bronze Age of Comic Books | |

|---|---|

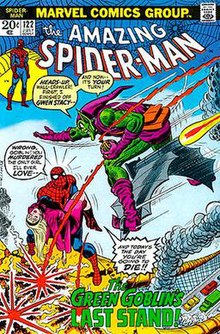

The Amazing Spider-Man #122 (July 1973) featuring the deaths of the Green Goblin and Gwen Stacy Cover art by John Romita Sr. | |

| Time span | 1970 – 1985[1] |

| Related periods | |

| Preceded by | Silver Age of Comic Books (1956–1970) |

| Followed by | Modern Age of Comic Books (1985–present) |

The Bronze Age retained many of the conventions of the Silver Age, with traditional superhero titles remaining the mainstay of the industry. However, a return of darker plot elements and storylines more related to relevant social issues began to flourish during the period, prefiguring the later Modern Age of Comic Books.[citation needed]

Origins

editThere is no one single event that can be said to herald the beginning of the Bronze Age. Instead, a number of events at the beginning of the 1970s, taken together, can be seen as a shift away from the tone of comics in the previous decade.

One such event was the April 1970 issue of Green Lantern, which added Green Arrow as a title character (Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76). The series, written by Denny O'Neil and penciled by Neal Adams (inking was by Adams or Dick Giordano), focused on "relevance" as Green Lantern was exposed to poverty and experienced self-doubt.[2][3]

Later in 1970, Jack Kirby left Marvel Comics, ending arguably the most important creative partnership of the Silver Age (with Stan Lee). Kirby then turned to DC, where he created The Fourth World series of titles, starting with Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #133 in December 1970. Also in 1970, Mort Weisinger, the long-term editor of the various Superman titles, retired to be replaced by Julius Schwartz. Schwartz set about toning down some of the more fanciful aspects of the Weisinger era, removing most Kryptonite from continuity and scaling back Superman's nigh-infinite—by then—powers, which was done by veteran Superman artist Curt Swan together with author Denny O'Neil.

The beginning of the Bronze Age coincided with the end of the careers of many of the veteran writers and artists of the time, or their promotion to management positions and retirement from regular writing or drawing, and their replacement with a younger generation of editors and creators, many of whom knew each other from their experiences in comic book fan conventions and publications. At the same time, publishers began the era by scaling back on their superhero publications, canceling many of the weaker-selling titles, and experimenting with other genres such as horror and sword and sorcery.[citation needed]

The era also encompassed major changes in the distribution of and audience for comic books. Over time, the medium shifted from cheap mass market products sold at newsstands to a more expensive product sold at specialty comic book shops and aimed at a smaller, core audience of fans. The shift in distribution allowed many small-print publishers to enter the market, changing the medium from one dominated by a few large publishers to a more diverse and eclectic range of books.[citation needed]

The 1970s

editIn 1970, Marvel published the first comic book issue of Robert E. Howard's pulp character Conan the Barbarian. Conan's success as a comic hero resulted in adaptations of other Howard characters: King Kull, Red Sonja and Solomon Kane. DC Comics responded with comics featuring Warlord, Beowulf and Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. They also took over the licensing of Edgar Rice Burroughs's Tarzan from longtime publisher Gold Key and began adapting other Burroughs creations, such as John Carter, the Pellucidar series, and the Amtor series. Marvel also adapted to comic book form, with less success, Edwin Lester Arnold's character Gullivar Jones and, later, Lin Carter's Thongor.

The murder of Spider-Man's longtime girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, at the hands of the Green Goblin in 1973's Amazing Spider-Man #121–122 is considered by comics scholar Arnold T. Blumberg to be the definitive Bronze Age event, as it exemplifies the period's trend towards darker territory and willingness to subvert conventions such as the assumed survival of long-established, "untouchable" characters. However, there had been a gradual darkening of the tone of superhero comics for several years prior to "The Night Gwen Stacy Died", including the death of her father in Amazing Spider-Man #90 and the beginning of the Dennis O'Neil/Neal Adams tenure on Batman.

In 1971, Marvel Comics' editor-in-chief Stan Lee was approached by the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare to do a comic book story about drug abuse. Lee agreed and wrote a three-part Spider-Man story, "Green Goblin Reborn!," which portrayed drug use as dangerous and unglamorous. At that time, any portrayal of drug use in comic books was banned outright by the Comics Code Authority, regardless of the context. The CCA refused to approve the story, but Lee published it regardless.

The positive reception that the story received led to the CCA revising the Comics Code later that year to allow the portrayal of drug addiction as long as it was depicted in a negative light. Soon after, DC Comics had their own drug abuse storyline in Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85–86. Written by Denny O'Neil with art by Neal Adams, the storyline was entitled "Snowbirds Don't Fly," and it revealed that the Green Arrow's sidekick Speedy had become addicted to heroin.

The 1971 revision to the Comics Code has also been seen as relaxing the rules on the use of vampires, ghouls and werewolves in comic books, allowing the growth of a number of supernatural- and horror-oriented titles, such as Swamp Thing, Ghost Rider and The Tomb of Dracula, among numerous others. However, the tone of horror comic stories had already seen substantial changes between the relatively tame offerings of the early 1960s (e.g. Unusual Tales) and the more violent products available in the late 1960s (e.g. The Witching Hour, revised formats in House of Secrets, House of Mystery and The Unexpected).

At the beginning of the 1970s, publishers moved away from the superhero stories that enjoyed mass-market popularity in the mid-1960s; DC cancelled most of its superhero titles other than those starring Superman and Batman, while Marvel cancelled weaker-selling titles such as Dr. Strange, Sub-Mariner and The X-Men. In their place, they experimented with a wide variety of other genres, including Westerns, horror and monster stories, and the above-mentioned adaptations of pulp adventures. These trends peaked in the early 1970s, and the medium reverted by the mid-1970s to selling predominantly superhero titles.[citation needed]

Further developments

editSocial relevance

editThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2022) |

A concern with social issues had been a part of comic book stories since their beginnings: early Superman stories, for example, dealt with issues such as child mistreatment and working conditions for minors. However, in the 1970s relevance became not only a feature of the stories, but also something that the books loudly proclaimed on their covers to promote sales. The Spider-Man drug issues were at the forefront of the trend of "social relevance" with comic books noticeably handling real-life issues. The above-mentioned Green Lantern/Green Arrow series dealt not only with drugs, but other topics like racism and environmental degradation. The X-Men titles, which were partly based on the premise that mutants were a metaphor for real-world minorities, became wildly popular. Other well-known "relevant" comics include the "Demon in a Bottle", where Iron Man confronts his alcoholism, and the socially conscious stories written by Steve Gerber in such titles as Howard the Duck and Omega the Unknown. Issues regarding female empowerment became trends with female versions of popular male characters (Spider-Woman, Red Sonja, Ms. Marvel, She-Hulk).

Creator credit and labor agreements

editWriters and artists began getting a lot more credit for their creations, even though they were still ceding copyrights to the companies for whom they worked. Pencil Artists were allowed to keep their original artwork and sell it on the open market. When word got out that Superman's creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were living in poverty, artists such as Neal Adams, Jerry Robinson and Bernie Wrightson helped organize fellow artists to pressure DC in rectifying them and other pioneers from the 1930s and 1940s. Newer publishers, such as Pacific Comics and Eclipse Comics, negotiated contracts in which creators retained copyright to their creations.

Minority superheroes

editOne of the most significant developments during the period was a substantial rise in the number of black and other non-white minority superheroes. Before the 1970s, there had been very few non-white superheroes (Marvel Comics' Black Panther and Falcon introduced in 1966 and 1969, respectively, being notable exceptions) but starting in the early 1970s this began to change with the introduction of characters such as Marvel's Luke Cage (who was the first black superhero featured in his own comic book in 1972) of the Defenders, Storm of the X-Men, Blade, Monica Rambeau of the Avengers, Misty Knight, Shang-Chi, and DC's Green Lantern John Stewart, Bronze Tiger, Black Lightning, Vixen and Cyborg of Teen Titans, many of whom were black (with the exception of Shang-Chi himself). Additionally, Jewish superheroes became more visible with the appearances of Marvel's Kitty Pryde of the X-Men and Moon Knight, respectively.

Characters such as Luke Cage, Mantis, Misty Knight, Shang-Chi and Iron Fist have been seen by some as an attempt by Marvel Comics to cash in on the 1970s crazes for kung fu films. However, these and other minority characters came into their own after these film trends faded, and became increasingly popular and important as time progressed. By the mid-1980s, Storm and Cyborg had become leaders of the X-Men and Teen Titans, respectively, and John Stewart briefly replaced Hal Jordan as the lead character of the Green Lantern title.

Art styles

editStarting with Neal Adams' work in Green Lantern/Green Arrow a newly sophisticated realism became the norm in the industry. Buyers would no longer be interested in the heavily stylized work of artists of the Silver Age or simpler cartooning of the Golden Age. The so-called "House Style" of DC tended to imitations of Adams' work, while Marvel adopted a more realistic version of Kirby's style. This change is sometimes credited to a new generation of artists influenced by the popularity of EC Comics in the 1950s. Artists who could distinguish themselves from these House Styles would achieve some renown. Such names include Berni Wrightson, Jim Aparo, Jim Starlin, John Byrne, Frank Miller, George Pérez and Howard Chaykin. A secondary line of comics at DC, headed by former EC Comics artist Joe Orlando and devoted to horror titles, established a differing set of styles and aggressively sought talent from Asia and Latin America.[citation needed]

Revival of the X-Men and the teen characters

editThe X-Men were originally created in 1963 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. However, the title never achieved the popularity of other Lee/Kirby creations, and by 1970, after a brief run with Neal Adams' more realistic Silver Age style, Marvel ceased publishing new material and the title was turned over to reprints. But in 1975 an "all-new, all-different" version of the X-Men was introduced by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum in Giant-Size X-Men #1, with Chris Claremont as uncredited assistant co-plotter.[4] Claremont stayed as writer on just about all X-Men-related titles, including spinoffs, for the next sixteen years, after which other regular writers such as Louise Simonson, Fabian Nicieza and Scott Lobdell joined and Claremont eventually left.

One of the most apparent influences from this series was the creation of what became DC Comics' answer to X-Men's character-based storytelling style, The New Teen Titans by Marv Wolfman and George Pérez, which became a highly successful and influential property in its own right. Wolfman would associate himself with the title for sixteen years, while Perez established a large fan base and a sought-after pencilling style. A successful cartoon based on the Titans of the Bronze Age of Comics was launched in 2003, and lasted for four years.[citation needed]

Team-up books and anthologies

editDuring the Silver Age, comic books frequently had several features, a form harkening back to the Golden Age when the first comics were anthologies. In 1968, Marvel graduated its double feature characters appearing in their anthologies to full-length stories in their own comic. But several of these characters could not sustain their own title and were cancelled. Marvel tried to create new double feature anthologies such as Amazing Adventures and Astonishing Tales which did not last as double feature comic books. A more enduring concept was that of the team-up book, either combining two characters, at least one of which was not popular enough to sustain its own title (Green Lantern/Green Arrow). Even DC combined two features in Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes and had team-up books (The Brave and the Bold, DC Comics Presents and World's Finest Comics). Virtually all such books disappeared by the end of the period.

Company crossovers

editMarvel and DC worked out several crossover titles the first of which was Superman vs. The Amazing Spider-Man. This was followed by a second Superman and Spider-Man, Batman vs. the Incredible Hulk and the X-Men vs The New Teen Titans. Another title, The Avengers vs. the Justice League of America was written by Gerry Conway and drawn by George Pérez with plotting by Roy Thomas, but was never published, reflecting the later animosity between the two companies. Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter was not pleased that DC wanted the fourth company crossover to include The New Teen Titans, DC's best-selling title at the time, as he wanted the crossover to be the X-Men and the Legion of Super-Heroes. This led to Shooter's decision to stall and cancel the JLA/Avengers project.[citation needed]

Reprints

editBeginning around 1970, Marvel introduced vast numbers of reprints into the market, which played a key role in their becoming the overall market leader among comic publishers. Suddenly many titles featured reprints: X-Men, Sgt. Fury, Kid Colt, Outlaw, Rawhide Kid, Two-Gun Kid, Outlaw Kid, Jungle Action, Special Marvel Edition (the early issues), War is Hell (the early issues), Creatures on the Loose, Monsters on the Prowl and FEAR, to name just a few.

DC Implosion

editIn the mid-'70s, DC launched numerous new titles such as Jack Kirby's New Gods and Steve Ditko's Shade, the Changing Man. Jenette Kahn would eventually take the helm of the company in 1976. The company followed this up in 1978 with the "DC Explosion" where the standard line of books increased in page count and 50 cent price. Many of these titles added backup features with various characters. However, DC greatly overestimated the appeal of so many new titles at once, sales dropped severely during the harsh 1978 winter and it nearly broke the company and the industry, including Charlton Comics; this event has been called the "DC Implosion".

Marvel eventually gained 50% of the market and Stan Lee handed control of the comic division to Jim Shooter while he worked with their growing animation spin-offs.

Non-superhero comics

editAs the Bronze Age began in the early 1970s, popularity shifted away from the established superhero genre towards comic book titles from which superheroes were absent altogether. These non-superhero comics were typically inspired by genres like Westerns or fantasy & pulp fiction. As previously noted, 1971's revised Comics Code left the horror genre ripe for development and several supernaturally-themed series resulted, such as the popular The Tomb of Dracula, Ghost Rider and Swamp Thing. In the science fiction genre, post-apocalyptic survival stories were an early trend, as evidenced by characters like Deathlok, Killraven and Kamandi. The long-running sci-fi/fantasy anthology comic magazine Metal Hurlant and its American counterpart Heavy Metal began publishing in the late '70s. Marvel's Star Wars series was very popular with a nine-year run.

Other titles began from characters originally found in 20th century pulp magazines or novels. Noteworthy examples are the long running titles Conan the Barbarian and Savage Sword of Conan (the latter was published as a magazine, bypassing the Comics Code), as well as Master of Kung-Fu. The early success of these titles soon led to more pulp character adaptations (Doc Savage, Kull, The Shadow, Justice, Inc., Tarzan). During this period, Charlton, Western Publishing/Gold Key, Marvel and DC also regularly published official comic book adaptations for various projects, including popular films (Planet of the Apes, Godzilla, Logan's Run, Indiana Jones, Jaws 2, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars), TV shows (The Six Million Dollar Man, Lost in Space, The Man from Atlantis, Battlestar Galactica, Star Trek, The A-Team, Welcome Back Kotter), toys (G.I. Joe, Micronauts, Transformers, Rom, Atari Force, Thundercats), and even public figures (Kiss, Pope John Paul II).

Though not necessarily "non-superhero", a few unconventional comic book series from the period featured one or more villains as their central character (Super-Villain Team-Up, Secret Society of Super Villains, The Joker).

Alternate markets and formats

editArchie Comics dominated the female market during this time with their characters, Betty and Veronica having some of the largest circulation of titular female characters. Several clones were attempted by Marvel and DC unsuccessfully. Several Archie titles examined socially relevant issues and introduced a few African-American characters. Archie largely switched to paperback digest format in the late 1980s.

Children's comics were still popular with Disney reprints under the Gold Key label along with Harvey's stable of characters which grew in popularity. The latter included Richie Rich, Casper and Wendy, which eventually switched to digest format as well. Again Marvel and DC were unable to emulate their success with competing titles.

An 'explicit content' market akin to the niche Underground Comix of the late '60s was ostensibly opened with the Franco-Belgian import Heavy Metal Magazine. Marvel launched competing magazine titles of their own with Conan the Barbarian and Epic Illustrated which would eventually become its division of Direct Sales comics.

The paper drives of World War II and a growing nostalgia among Baby-Boomers in the 1970s made comic books of the 1930s and 1940s extremely valuable. DC experimented with some large-size paperback books to reprint their Golden Age comics, create one-shot stories such as Superman vs. Shazam and Superman vs. Muhammad Ali as well as the early Marvel crossovers.

The popularity of those early books also opened up a market for specialty shops. The existence of these shops made it possible for small-press publishers to reach an audience, and some comic book artists began self-publishing their own work. Notable titles of this type included Dave Sim's Cerebus and Wendy and Richard Pini's Elfquest series. Other small-press publishers came in to take advantage of this growing market: Pacific Comics introduced in 1981 a line of books by comic-book veterans such as Jack Kirby, Mike Grell and Sergio Aragonés, for which the artists retained copyright and shared in royalties.

In 1978, Will Eisner published his "graphic novel" A Contract With God, an attempt to produce a long-format story outside the traditional comic book genres. In the early 1980s Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly began publishing Raw magazine, which included the early serialization of Spiegelman's award-winning graphic novel Maus.

Comics sold on newsstands were distributed on the basis that unsold copies were returned to the publisher. Comics sold to comic shops were sold on a no-return basis. This allowed small-press titles sold through the direct market to keep publishing costs down and increase profits, making viable titles that otherwise would have been unprofitable. Marvel and DC began taking advantage of this direct market themselves, publishing books and titles distributed only through comic book shops.

Disappearing genres

editThis period is also marked by the cancellation of most titles in the genres of romance, western, and war stories that had been mainstays of comics production since the 1940s. Most anthologies, whether they presented feature characters or not, also disappeared. They had been used since the Golden Age to introduce new characters, to host characters that lost their own title or to feature several characters. This had the effect of standardizing the length of comics stories within a narrow range, so that multiple stand-alone stories would appear within a single issue. The underground comix of the 1960s counterculture continued, but contracted significantly and were ultimately subsumed into the emerging direct market.

End

editOne commonly used ending point for the Bronze Age is the 1985–1986 time frame.[citation needed] As with the Silver Age, the end of the Bronze Age relates to a number of trends and events that happened at around the same time. DC Comics published Crisis on Infinite Earths, which overhauled the history of the DC Universe and several of the company's major characters, and revitalized sales for the company, again making it a serious market contender against Marvel. During this period Marvel published the crossover Secret Wars, cancelled Defenders and Power Man and Iron Fist, and launched the New Universe and X-Factor (an extension of the X-Men franchise).

After the Bronze Age came the Modern Age of Comic Books. According to Shawn O'Rourke of PopMatters, the shift from the previous ages involved a "deconstructive and dystopian re-envisioning of iconic characters and the worlds that they live in",[5] as typified by Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and Alan Moore's and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen (1986–1987). Other features that define the era are a higher amount of adult-oriented material, the X-Men becoming Marvel Comics' "dominant intellectual property", and the comics distribution system being reorganized throughout the industry.[5] These changes would also lead to the appearance of new independent comic book publishers in the early 1990s—such as Image Comics, with titles like Spawn and Savage Dragon which also boasted a darker, sarcastic and more mature approach to superhero storylines.

Noted talents

editTimeline

edit- January 1970: First Denny O'Neil/Neal Adams Batman story (The Secret of the Waiting Graves, Detective Comics #395) signals a darker era for the iconic character. Ward Dick Grayson (Robin) left for college, and alter ego Bruce Wayne left Wayne Manor, in previous month's Batman comic.

- April 1970: DC Comics adds Green Arrow to Green Lantern book for stories written by Denny O'Neil and penciled by Neal Adams featuring "relevance". Series, story, writer, penciller and inker all win first Shazam Awards in their respective categories the following year.

- October 1970: Marvel Comics begins publishing Conan the Barbarian.

- October 1970: DC Comics begins publishing Jack Kirby's Fourth World titles beginning with Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen and continuing with New Gods, The Forever People and Mister Miracle.

- 1971: The Comics Code is revised.

- January 1971: Clark Kent becomes a newscaster at WGBS-TV.

- February 1971: African-American superhero Falcon shares co-feature status in renamed Captain America and The Falcon.

- July 1971: DC Comics introduces the character of Swamp Thing in its House of Secrets title.

- April 1972: Marvel begins publishing The Tomb of Dracula.

- June 1972: Luke Cage becomes the first African American superhero to receive his own series in Hero for Hire #1.

- June 1973: Green Goblin kills Gwen Stacy in Amazing Spider-Man #121.

- December 1973: The absurdist Howard the Duck makes his first appearance in comics and would be one of the most popular non-superheroes ever. He would get his own series in 1976 and he would graduate to his own daily newspaper strip and a 1986 film.

- February 1974: First appearance of the Punisher in The Amazing Spider-Man #129.

- November 1974: First appearance of Wolverine in Incredible Hulk #181.

- 1975: Giant-Size X-Men #1 by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum introduces the "all-new, all-different X-Men."

- July 1977: At the request of Roy Thomas, Marvel releases Star Wars, based on the hit movie, and it quickly becomes one of the best-selling books of the era.

- August 1977: Black Manta kills Aquababy in Adventure Comics #452.

- December 1977: Dave Sim launches Cerebus independent of the major publishers, the longest-running limited series (300 issues) in comics as well as the longest run by one artist on a comic book series.

- Spring 1978: First appearance of Elfquest by Wendy and Richard Pini is published in Fantasy Quarterly.

- 1978: DC cancels over half of its titles in the so-called DC Implosion.

- July 1979: DC publishes World of Krypton, the first comic book mini-series, which gave publishers a new flexibility with titles.

- January – October 1980: "The Dark Phoenix Saga" (Uncanny X-Men)

- November 1980: First issue of DC Comics' The New Teen Titans whose success at revitalizing a previously underperforming property would lead to the idea of revamping the entire DC Universe.

- June 1982: Marvel publishes Contest of Champions, its first limited series. This title features most of the company's major characters together, providing a template for later limited-series storylines at Marvel and DC.

- October 1982: Comico begins publishing a comic called Comico Primer that would later be the starting point for several influential artists and writers such as Sam Kieth and Matt Wagner.

- May 1984: Marvel begins releasing the first "big event" storyline, Secret Wars, which would, along with Crisis on Infinite Earths, popularize big events, and make them a staple in the industry.

- May 1984: Mirage Studios begins publishing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles by Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird.

- Summer 1984: DC Comics, desiring to feature more diverse characters, adds Vixen, Vibe (and Steel) to the Justice League of America, with Aquaman as team leader and later Batman. This was commonly known as "Justice League Detroit Era".

- April 1985: DC begins publishing Crisis on Infinite Earths, which would drastically restructure the DC universe, and popularize the epic crossover in the comics industry along with Secret Wars. In the aftermath of this Crisis, DC cancels and relaunches the Flash, Superman and Wonder Woman.

- August 1985: Eclipse Comics publishes Miracleman, written by Alan Moore, developing the later trends of bringing superhero fiction into the real world, and showing the effects of immensely powerful characters on global politics (both potentially apocalyptic and utopian).

- 1986: DC publishes Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, setting a new grim tone for Batman.

- September 1986: Curt Swan, primary Superman artist during the Silver and Bronze Age, is retired from his monthly art duties on all Superman books after the last Pre-Crisis Superman story, called "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?", on which he worked together with Alan Moore, is published.

- September 1986 – October 1987: DC Comics publishes the Watchmen limited series, seen by many as a model for a new age of comics.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Bronze Age Comics (1970–1985)".

- ^ Jacobs, Will, Gerard Jones (1985). The Comic Book Heroes: From the Silver Age to the Present. New York, New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 0-517-55440-2, p. 154.

- ^ "Scott's Classic Comics Corner: A New End to the Silver Age Pt. 1" Archived 18 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ^ Chris Claremont's role in this issue is mentioned in Official Marvel Index to the X-Men #4, November 1987

- ^ a b O'Rourke, Shawn (22 February 2008). "A New Era: Infinite Crisis, Civil War, and the End of the Modern Age of Comics". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2008.