The Bends is the second studio album by the English rock band Radiohead, released on 13 March 1995 by Parlophone. It was produced by John Leckie, with extra production by Radiohead, Nigel Godrich and Jim Warren. The Bends combines guitar songs and ballads, with more restrained arrangements and cryptic lyrics than Radiohead's debut album, Pablo Honey (1993).

| The Bends | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 13 March 1995 | |||

| Recorded | 1993 ("High and Dry") February–November 1994 | |||

| Venue | London Astoria, London | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 48:33 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer |

| |||

| Radiohead chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Bends | ||||

| ||||

Work began at RAK Studios, London, in February 1994. Tensions were high, with pressure from Parlophone to match sales of Radiohead's debut single, "Creep", and progress was slow. After an international tour in May and June, Radiohead resumed work at Abbey Road in London and the Manor in Oxfordshire. The Bends was the first Radiohead album recorded with Godrich and the artist Stanley Donwood, who have worked on every Radiohead album since.

Several singles were released, backed by music videos: "My Iron Lung", the double A-side "High and Dry / Planet Telex", "Fake Plastic Trees", "Just", and Radiohead's first top-five entry on the UK singles chart, "Street Spirit (Fade Out)". "The Bends" was also released as a single in Ireland. A live video, Live at the Astoria, was released on VHS. Radiohead toured extensively for The Bends, including US tours supporting R.E.M. and Alanis Morissette.

The Bends reached number four on the UK Albums Chart, but failed to build on the success of "Creep" outside the UK, reaching number 88 on the US Billboard 200. It received greater acclaim than Pablo Honey, including a nomination for Best British Album at the Brit Awards 1996, and elevated Radiohead from one-hit-wonders to one of the most recognised British bands. It is frequently named one of the greatest albums of all time, cited in lists including Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums and all three editions of Rolling Stone's lists of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. The Bends is credited for influencing a generation of post-Britpop acts, such as Coldplay, Muse and Travis. It is certified platinum in the US and quadruple platinum in the UK.

Background

editRadiohead released their debut album, Pablo Honey, in 1993. By the time they began their first US tour early that year, their debut single, "Creep", had become a hit.[1] The band felt pressured by the success and mounting expectations.[2] Following the tours, the singer, Thom Yorke, became ill and Radiohead cancelled an appearance at the 1993 Reading Festival. He told NME: "Physically I'm completely fucked and mentally I've had enough."[3]

According to some reports, Radiohead's record company, EMI, gave them six months to "get sorted" or be dropped. EMI's A&R head, Keith Wozencroft, denied this, saying: "Experimental rock music was getting played and had commercial potential. People voice different paranoias, but for the label [Radiohead] were developing brilliantly from Pablo Honey."[3]

After Radiohead finished recording Pablo Honey, Yorke played the co-producer Paul Q. Kolderie a demo tape of new material with the working title The Benz. Kolderie was shocked to find the songs were "all better than anything on Pablo Honey".[3] The guitarist Ed O'Brien later said: "After all that touring on Pablo Honey ... the songs that Thom was writing were so much better. Over a period of a year and a half, suddenly, bang."[4] Kolderie credited Radiohead's Pablo Honey tours for "turning them into a tight band".[5]

To produce their next album, Radiohead selected John Leckie, who had produced records by acts they admired, such as Magazine.[3][6] The drummer, Philip Selway, said Radiohead were reassured by how relaxed and open-minded Leckie was on their first meeting.[6] According to O'Brien, the success of "Creep" meant that Radiohead were not in debt to EMI and so had more freedom on their next album.[7] EMI asked Radiohead to deliver a followup to "Creep" for the American market; however, according to Leckie, Radiohead had disowned "Creep" and did not "think in terms of making hit singles".[3]

Recording was postponed so Leckie could work on the album Carnival of Light, by another Oxford band, Ride.[8] Radiohead used the extra time to rehearse in a disused barn on an Oxfordshire fruit farm in January 1994.[9][10] Yorke said: "We had all of these songs and we really liked them, but we knew them almost too well ... so we had to sort of learn to like them again before we could record them, which is odd."[9]

Recording

editEMI gave Radiohead nine weeks to record the album,[3] planning to release it in October 1994.[11] Work began at RAK Studios in London in February 1994.[2] Yorke would arrive at the studio early and work alone at the piano; according to Leckie, "New songs were pouring out of him."[3] The band praised Leckie for demystifying the studio environment. The guitarist Jonny Greenwood said: "He didn't treat us like he had some kind of witchcraft that only he understands. There's no mystery to it, which is so refreshing."[12]

The sessions saw Radiohead's first collaboration with their future producer, Nigel Godrich, who engineered the RAK sessions. When Leckie left the studio to attend a social engagement, Godrich and the band stayed to record B-sides. One song, "Black Star", was included on the album.[11]

Whereas Pablo Honey was mostly written by Yorke, The Bends saw greater collaboration.[11] Previously, all three guitarists had often played identical parts, creating a "dense, fuzzy wall" of sound. Their Bends roles were more divided, with Yorke generally playing rhythm, Greenwood lead and Ed O'Brien providing effects.[11] O'Brien described the Boss DD-5, a delay pedal, as important to the album's sound.[13] The band also created more restrained arrangements; in O'Brien's words, "We were very aware of something on The Bends that we weren't aware of on Pablo Honey... If it sounded really great with Thom playing acoustic with Phil and [Colin], what was the point in trying to add something more?"[11]

"Planet Telex" began with a drum loop taken from another song, the B-side "Killer Cars", and was written and recorded in a single evening at RAK.[14] "(Nice Dream)" began as a simple four-chord song by Yorke, and was expanded with extra parts by O'Brien and Greenwood. Much of "Just" was written by Greenwood, who, according to Yorke, "was trying to get as many chords as he could into a song".[11] Not satisfied with the versions of "My Iron Lung" recorded at RAK, Radiohead used a live recording from the London Astoria, with Yorke's vocals replaced and the audience removed.[12]

Radiohead made several efforts to record "Fake Plastic Trees". O'Brien likened one version to the Guns N' Roses song "November Rain", saying it was "pompous and bombastic ... just the worst".[11] Eventually, Leckie recorded Yorke playing "Fake Plastic Trees" alone, which the rest of the band used to build the final song.[11] "High and Dry" was recorded the previous year at Courtyard Studios, Oxfordshire, by Radiohead's live sound engineer, Jim Warren.[11] Yorke later said it was a "very bad" song that EMI had pressured him into releasing.[15]

"The Bends", "(Nice Dream)" and "Just" were identified as potential singles and became the focus of the early sessions, which created tension.[16] Leckie recalled: "We had to give those absolute attention, make them amazing, instant smash hits, number one in America. Everyone was pulling their hair out saying, 'It's not good enough!' We were trying too hard."[16] Yorke in particular struggled with the pressure, and Radiohead's co-manager Chris Hufford considered quitting, citing Yorke's "mistrust of everybody".[16] Jonny Greenwood spent days testing new guitar equipment, searching for a distinctive sound, before reverting to his Telecaster.[16][3] The bassist, Colin Greenwood, described the period as "eight weeks of hell and torture".[17] According to Yorke, "We had days of painful self-analysis, a total fucking meltdown for two fucking months."[11] O'Brien said each member examined their options for leaving their contracts.[18]

With the October deadline abandoned, recording paused in May and June while Radiohead toured Europe, Japan and Australasia.[11] Work resumed for two weeks in July at the Manor studio in Oxfordshire, where Radiohead completed songs including "Bones", "Sulk" and "The Bends".[16] This was followed by tours of the UK, Thailand and Mexico. In Mexico, the band members had a major argument.[18] Yorke said: "Years of tension and not saying anything to each other, and basically all the things that had built up since we'd met each other, all came out in one day. We were spitting and fighting and crying and saying all the things that you don't want to talk about. It completely changed and we went back and did the album and it all made sense."[18] The tour gave Radiohead a new sense of purpose and their relationships improved. Hufford encouraged them to make the album they wanted instead of worrying about "product and units".[16]

Recording ended in November 1994 at Abbey Road Studios in London.[11][19] Selway said the album was recorded in about four months total.[6] Leckie mixed some of The Bends at Abbey Road.[19] With deadlines approaching, EMI grew concerned that he was taking too long. Without his knowledge, they sent tracks to Sean Slade and Paul Q. Kolderie, who had produced Pablo Honey, to mix instead. Leckie disliked their mixes, finding them "brash", but later said: "I went through a bit of trauma at the time, but maybe they chose the best thing."[3] Only three of Leckie's mixes were used on the album.[3]

Music

editThe Bends has been described as alternative rock[20] and indie rock.[21] Like Pablo Honey, it features guitar-oriented rock songs, but its songs are "more spacey and odd", according to The Gazette's Bill Reed.[22] The music is more eclectic than Pablo Honey;[23] Colin Greenwood said Radiohead wanted to distinguish themselves from Pablo Honey and that The Bends better represented their style.[24] Pitchfork wrote that it contrasts warmth and tension, riffs and texture, and rock and post-rock.[25] Several critics identified it as a Britpop album, though Radiohead disliked Britpop, seeing it as a "backwards-looking" pastiche.[26][27][28]

The critic Simon Reynolds wrote that The Bends brought an "English art rock element" to the fore of Radiohead's sound.[29] According to Kolderie, "The Bends was neither an English album nor an American album. It's an album made in the void of touring and travelling. It really had that feeling of, 'We don't live anywhere and we don't belong anywhere.'"[16] Reed described the album as "intriguingly disturbed" and "bipolar". He likened "The Bends" to the late music of the Beatles, described "My Iron Lung" as hard rock, and noted more subdued sounds on "Bullet Proof ... I Wish I Was" and "High and Dry", showcasing Radiohead's "more plaintive and meditative side".[22]

Rolling Stone described The Bends as a "mix of sonic guitar anthems and striking ballads", with lyrics evoking a "haunted landscape" of sickness, consumerism, jealousy and longing.[30] Several songs evoke a "sense of a disintegrated or disconnected subject".[31] The journalist Mac Randall described the lyrics as "a veritable compendium of disease, disgust and depression" that nonetheless become uplifting in the context of the "inviting" and "powerful" arrangements.[11] Jonny Greenwood said The Bends was about "illness and doctors... revulsion about our own bodies".[18] Yorke said it was "an incredibly personal album, which is why I spent most of my time denying that it was personal at all".[18] The album title, a term for decompression sickness, references Radiohead's rapid rise to fame with "Creep". Yorke said, "We just came up too fast."[32]

In "Fake Plastic Trees", Yorke laments the effects of consumerism on modern relationships.[31] It was inspired by the commercial development of Canary Wharf and a performance by Jeff Buckley, who inspired Yorke to use falsetto.[33][34] Sasha Frere-Jones compared its melody to the "second theme of a Schubert string quartet".[35] In "Just", Jonny Greenwood plays octatonic scales that extend over four octaves,[36] influenced by the 1978 Magazine song "Shot By Both Sides".[37] With the use of a DigiTech Whammy pedal, Greenwood pitch-shifts the solo into a high, piercing frequency.[5][38] Greenwood also uses the Whammy for the opening riff of "My Iron Lung", creating a "glitchy, lo-fi" sound.[39] According to Randall, "My Iron Lung" transitions from a "jangly" opening hook to a "McCartney-esque verse melody" and "pulverising guitar explosions" in the bridge.[11]

"Sulk" was written as a response to the Hungerford massacre. It originally ended with the lyric "just shoot your gun". Yorke omitted it after the suicide of the Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain in 1994, as he did not want listeners to believe it was an allusion to Cobain.[40] "Street Spirit (Fade Out)" was inspired by R.E.M. and the 1991 novel The Famished Road by Ben Okri;[41] the lyrics detail an escape from an oppressive reality.[31] The journalist Rob Sheffield described "Street Spirit", "Planet Telex" and "High and Dry" as a "big-band dystopian epic".[42]

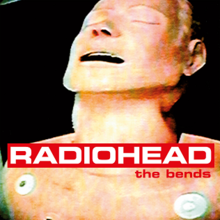

Artwork

editThe Bends was the first Radiohead album with artwork by Stanley Donwood. Donwood met Yorke while they were students at the University of Exeter, and previously created artwork for the My Iron Lung EP. With Yorke, Donwood has created all of Radiohead's artwork since.[43]

For The Bends, Yorke and Donwood hired a cassette camera and filmed objects including road signs, packaging and street lights. They entered a hospital to film an iron lung, but, according to Donwood, found that iron lungs "are not very interesting to look at". Instead, they filmed a CPR mannequin, which Donwood described as having "a facial expression like that of an android discovering for the first time the sensations of ecstasy and agony, simultaneously".[44] To create the cover image, the pair displayed the footage on a television set and photographed the screen.[44]

Release

editIn September 1994, EMI released the My Iron Lung EP, comprising "My Iron Lung" plus Bends outtakes.[11] "My Iron Lung" was also released as a single.[45] The A&R VP Perry Watts-Russel said EMI did not pursue radio play as "My Iron Lung" was intended for fans rather than as the lead single for The Bends.[46]

The Bends was released at the height of Britpop, when the British music charts were dominated by bands such as Oasis and Blur, and initially made little impact.[47] It was released in Japan on 8 March 1995 by EMI,[48] and in the UK on 13 March by Parlophone Records.[49] It spent 16 weeks on the UK Albums Chart, reaching number four.[50] On the same day as the UK release, Radiohead's performance at the London Astoria in May 1994 was released on VHS as Live at the Astoria,[51] including several Bends tracks.[52]

In the US, The Bends was released on 4 April by EMI's North American subsidiary, Capitol Records.[49] According to the journalist Tim Footman, Capitol almost refused to release it, feeling it lacked hit singles.[53] It debuted at the bottom of the US Billboard 200 in the week of 13 May[54] and reached number 147 in the week of 24 June.[55] It re-entered the chart in the week of 17 February 1996,[56] and reached number 88 on 20 April,[57] almost exactly a year after its release. On 4 April, The Bends was certified gold in the US for sales of half a million copies.[58] Though it remains Radiohead's lowest-charting album in the US, it was certified platinum in January 1999 for sales of one million copies.[59]

Interest from influential musicians such as the R.E.M. vocalist Michael Stipe, combined with several distinctive music videos, helped sustain Radiohead's popularity outside the UK.[60] "Fake Plastic Trees" was used in the 1995 film Clueless and is credited for introducing Radiohead to a larger American audience.[61] According to the MTV host Matt Pinfield, record companies would ask why MTV kept promoting The Bends when it was selling less than their albums; his reply was: "Because it's great!"[62] Yorke thanked Pinfield by giving him a gold record of The Bends.[62]

The Bends slowly found fans through word of mouth.[47] Selway credited the videos for helping The Bends "gradually seep into people's consciousness".[63] Colin Greenwood wrote later: "I spoke to so many music writers who'd received The Bends as a promo, left it to gather dust on top of their PC tower, and hadn't bothered to play it until word of mouth nudged them."[47] By the end of 1996, The Bends had sold around two million copies worldwide.[64] In the UK, it was certified platinum in February 1996 for sales of over 300,000, and was certified quadruple platinum in July 2013.[65]

Singles

editAccording to Hufford, American audiences were disappointed by the lack of a "Creep"-style song on The Bends. In response, Capitol chose "Fake Plastic Trees" as the first US single, to further distance Radiohead from "Creep".[66] It failed to enter the US Billboard Hot 100, but reached number 20 on the UK Singles Chart.[14] "Just", released in the UK on August 21, reached number 19. It was not released as a single in the US, but its music video, directed by Jamie Thraves, received attention there.[14] The next US single, the double A-side "High and Dry" and "Planet Telex", reached number 78.[14] "Street Spirit (Fade Out)", released in January 1996, reached number five on the UK Singles Chart, surpassing "Creep" and demonstrating that Radiohead were not one-hit wonders.[14] "The Bends" was released as a single in Ireland and reached number 26 on the Irish Singles Chart in August 1996.[67]

Tours

editRadiohead toured extensively for The Bends, with performances in North America, Europe and Japan.[14] They first toured in support of Soul Asylum, then R.E.M., one of their formative influences and one of the world's biggest rock bands at the time.[60] Yorke said about the tour with R.E.M: "Everything that we've come to expect was completely turned on its head. Like the idea that you get to a certain level and you lose it. Everything was amicable and there was no bitchiness or pettiness about it."[66]

The American tour included a performance at the KROQ Almost Acoustic Christmas concert at the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles, alongside Oasis, Alanis Morissette, No Doubt and Porno for Pyros. The Capitol employee Clark Staub described the performance as a "key stepping stone" for Radiohead in the US.[14]

Before a performance in Denver, Colorado, Radiohead's tour van was stolen and with it their musical equipment. Yorke and Jonny Greenwood performed a stripped-down set with rented instruments and several shows were cancelled. Greenwood was reunited with his stolen Fender Telecaster Plus in 2015 after a fan recognised it as one they had purchased in Denver in the 1990s.[68] In November 1995, Yorke became sick and collapsed on stage at a show in Munich. NME covered the incident in a story titled "Thommy's Temper Tantrum". Yorke said it was the most hurtful thing anyone had written about him, and refused to give interviews to NME for five years.[18]

In March 1996, Radiohead toured the US again and performed on The Tonight Show and 120 Minutes. In mid-1996, they played at European festivals including Pinkpop in Holland, Tourhout Werchter in Belgium and T in the Park in Scotland.[14] That August, Radiohead toured as the opening act for Alanis Morissette,[69] performing early versions of songs from their next album, OK Computer.[70] Morissette said later: "It was really grounding for me to be with such bona-fide-to-the-bone artists. It felt really validating because the industry was very wild and patriarchal, so to be on the road with such true savants was a gift for me."[7]

Critical reception

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Chicago Tribune | [71] |

| Entertainment Weekly | B+[72] |

| The Guardian | [73] |

| Los Angeles Times | [74] |

| NME | 9/10[21] |

| Q | [75] |

| Rolling Stone | [76] |

| Select | 4/5[77] |

| Spin | 5/10[78] |

| The Village Voice | C[79] |

The Bends brought Radiohead significant critical attention.[22] The Guardian critic Caroline Sullivan wrote that Radiohead had "transformed themselves from nondescript guitar-beaters to potential arena-fillers ... The grandeur may eventually pall, as it has with U2, but it's been years since big bumptious rock sounded this emotional."[73] Q described The Bends as a "powerful, bruised, majestically desperate record of frighteningly good songs",[75] while NME's Mark Sutherland wrote that "Radiohead clearly resolved to make an album so stunning it would make people forget their own name, never mind ['Creep']", describing it as "the consummate, all-encompassing, continent-straddling '90s rock record".[21] Dave Morrison of Select wrote that it "captures and clarifies a much wider trawl of moods than Pablo Honey" and praised Radiohead as "one of the UK's big league, big-rock assets".[77] NME and Melody Maker named The Bends among the top ten albums of the year.[23]

Critical reception in the United States was mixed. Chuck Eddy of Spin deemed much of the album "nodded-out nonsense mumble, not enough concrete emotion",[78] while Kevin McKeough from the Chicago Tribune panned Yorke's lyrics as "self-absorbed" and the music as overblown and pretentious.[71] In The Village Voice, Robert Christgau wrote that the guitar parts and expressions of angst were skilful and natural, but lacked depth: "The words achieve precisely the same pitch of aesthetic necessity as the music, which is none at all."[79] In the Los Angeles Times, Sandy Morris praised Yorke as "almost as enticingly enigmatic as Smashing Pumpkins' Billy Corgan, though of a more delicate constitution".[74]

In 1997, Jonny Greenwood said The Bends had been a "turning point" for Radiohead: "It started appearing in people's [best of] polls for the end of the year. That's when it started to feel like we made the right choice about being a band."[80] The success gave Radiohead the confidence to self-produce their next album, OK Computer (1997), with Godrich.[81]

Legacy

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [82] |

| The A.V. Club | A[83] |

| Blender | [84] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [85] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A[86] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[87] |

| Q | [88] |

| Rolling Stone | [89] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [42] |

| Uncut | [90] |

In 2015, Selway said The Bends had marked the origin of the "Radiohead aesthetic", aided by Donwood's artwork.[6] The journalist Rob Sheffield recalled that The Bends "shocked the world", elevating Radiohead from "pasty British boys to a very 70s kind of UK art-rock godhead".[42] It attracted interest from high-profile musicians and film stars.[29]

Two years after its release, the Guardian critic Caroline Sullivan wrote that The Bends had taken Radiohead from "indie one hit-wonder" into the "premier league of respected British rock bands".[91] The Rolling Stone journalist Jordan Runtagh wrote in 2012 that The Bends was "a musically dense and emotionally complex masterwork that erased their one-hit-wonder status forever".[92] The writer Nick Hornby wrote in 2000 that, with The Bends, Radiohead "found their voice ... No other contemporary band has managed to mix such a cocktail of rage, sarcasm, self-pity, exquisite tunefulness and braininess."[93]

In Pitchfork, Scott Plagenhoef wrote that The Bends presented a "more approachable and loveable version" of Radiohead and remained many fans' favourite album.[25] He argued that it presented a transition from Britpop to "the more feminine, emotionally engaging music that would emerge in the UK a few years later", led by OK Computer.[25]

Influence

editThe Bends influenced a generation of British and Irish acts, including Coldplay, Keane, James Blunt, Muse, Athlete, Elbow, Snow Patrol, Kodaline, Turin Brakes and Travis.[28][33] Pitchfork credited songs as such as "High and Dry" and "Fake Plastic Trees" for anticipating the "airbrushed" post-Britpop of Coldplay and Travis.[28] Acts including Garbage, R.E.M. and k.d. lang began to cite Radiohead as a favourite band.[94] The Cure contacted Radiohead to inquire about the Bends production in the hope of replicating it.[23]

In 2006, The Observer named The Bends one of "the 50 albums that changed music", saying it had popularised an "angst-laden falsetto ... a thoughtful opposite to the chest-beating lad-rock personified by Oasis", which "eventually coalesced into an entire decade of sound".[95] Yorke held contempt for the style of rock The Bends popularised, feeling other acts had copied him. He said in 2006: "I was really, really upset about it, and I tried my absolute best not to be, but yeah, it was kind of like— that sort of thing of missing the point completely."[96] Godrich felt Yorke was oversensitive and told him he did not invent "guys singing in falsetto with an acoustic guitar".[7]

Accolades

editIn 2000, in a vote of more than 200,000 music fans and journalists, The Bends was named the second-greatest album of all time behind Revolver (1966) by the Beatles.[97] Q readers voted it the second-best album in 1998 and 2006, behind OK Computer.[98][99] Colin Larkin named it the second-best album of all time in the 2000 edition of All Time Top 1000 Albums.[100] It was included in the 2005 book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[101] Rolling Stone placed it at number 110 on its original 2003 list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, at 111 in its 2012 list,[102] and at 276 in its 2020 list.[103] In 2006, it reached number 10 in a worldwide poll of the great albums organised by British Hit Singles & Albums and NME.[104] Paste named it the 11th-greatest album of the 1990s.[105] In 2020, the Independent named it the best album of 1995, writing: "Downbeat, melancholic, yet wonderfully melodic and uplifting ... The Bends stood apart from Britpop and everything else in the storied year of 1995."[106] In 2017, Pitchfork named The Bends the third-greatest Britpop album, writing that its "epic portrayal of drift and disenchantment secures its reluctant spot in Britpop's pantheon".[28]

Reissues

editRadiohead left EMI after their contract ended in 2003.[107] In 2007, EMI released Radiohead Box Set, a compilation of albums recorded while Radiohead were signed to EMI, including The Bends.[107] On 31 August 2009, EMI reissued The Bends and other Radiohead albums in a "Collector's Edition" compiling B-sides and live performances. Radiohead had no input into the reissue and the music was not remastered.[108][25][109]

In February 2013, Parlophone was bought by Warner Music Group (WMG).[110] In April 2016, as a result of an agreement with the trade group Impala, WMG transferred Radiohead's back catalogue to XL Recordings. The EMI reissues, released without Radiohead's consent, were removed from streaming services.[111] In May 2016, XL reissued Radiohead's back catalogue on vinyl, including The Bends.[112]

Track listing

editAll songs written by Radiohead.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Planet Telex" | 4:19 |

| 2. | "The Bends" | 4:06 |

| 3. | "High and Dry" | 4:17 |

| 4. | "Fake Plastic Trees" | 4:50 |

| 5. | "Bones" | 3:09 |

| 6. | "(Nice Dream)" | 3:53 |

| 7. | "Just" | 3:54 |

| 8. | "My Iron Lung" | 4:36 |

| 9. | "Bullet Proof ... I Wish I Was" | 3:28 |

| 10. | "Black Star" | 4:07 |

| 11. | "Sulk" | 3:42 |

| 12. | "Street Spirit (Fade Out)" | 4:12 |

| Total length: | 48:33 | |

Personnel

editAdapted from the liner notes.[113]

|

Radiohead

Additional musicians

|

Production

Design

|

Charts

edit

Weekly chartsedit

|

Year-end chartsedit

|

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[133] | Gold | 30,000^ |

| Belgium (BEA)[134] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[135] | 3× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[136] sales since 2009 |

Gold | 25,000‡ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[137] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[138] | Platinum | 15,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[140] | 4× Platinum | 1,248,350[139] |

| United States (RIAA)[142] | Platinum | 1,540,000[141] |

| Summaries | ||

| Europe (IFPI)[143] | Platinum | 1,000,000* |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

edit- ^ "Creepshow", Melody Maker, 19 December 1992

- ^ a b Black, Johnny (1 June 2003), "The Greatest Songs Ever! Fake Plastic Trees", Blender, archived from the original on 9 April 2007, retrieved 15 April 2007

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Monroe, Jazz (13 March 2019). "Radiohead's The Bends: inside the anti-capitalist, anti-cynicism classic". NME. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ McLean, Craig (6 February 2020). "Radiohead guitarist Ed O'Brien steps up". The Face. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ a b Randall, Mac (2011). Exit Music: The Radiohead Story. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1849384575.

- ^ a b c d "Q&A: Radiohead's Philip Selway remembers The Bends". Stereogum. 9 March 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Greene, Andy (16 June 2017). "Radiohead's OK Computer: an oral history". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 125.

- ^ a b Randall 2000, p. 126.

- ^ "Radiohead sketchbook sells for £5,000 after auction". BBC News. 24 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Randall, Mac (15 May 2015). "Radiohead's The Bends 20 years later: reexamining a modern rock masterpiece". Guitar World. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ a b Garcia, Sandra (July 1995). "Decompression". B-Side (51).

- ^ Astley-Brown, Michael (29 December 2023). ""It's the only delay that can make those OK Computer sounds": Ed O'Brien explains why one BOSS pedal was integral to Radiohead's landmark '90s albums". Guitar World. Archived from the original on 30 December 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Randall 2012.

- ^ Plagenhoef, Scott (16 August 2006). "Interviews: Thom Yorke". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Irvin, Jim; Hoskyns, Barney (July 1997). "We Have Lift-Off!". Mojo (45).

- ^ Robinson, Andrea (August 1997). "Radio days". The Mix. Future Publishing.

- ^ a b c d e f Dalton, Stephen (18 March 2016). "Radiohead: 'We were spitting and fighting and crying...'". Uncut. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ a b Randall 2000, p. 133.

- ^ Kane, Tyler (20 October 2012). "Radiohead's Discography Ranked". Paste. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Sutherland, Mark (18 March 1995). "Radiohead – The Bends". NME. London. Archived from the original on 17 August 2000. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Reed, Bill (22 August 2003). "Tune in, tune on to Radiohead". The Gazette. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Bauder, David (29 March 1996). "Radiohead: Band's 'Bends' album has stylistic, diverse sound". The Daily Herald. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Wener, Ben (21 July 1997). "Yes, we have no message". Orange County Register. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Plagenhoef, Scott (16 April 2009). "Radiohead: Pablo Honey: Collector's Edition / The Bends: Collector's Edition / OK Computer: Collector's Edition". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Taysom, Joe (24 November 2022). "Why Radiohead hated "backwards-looking" Britpop". Far Out. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Pappademas, Alex (23 June 2003). "The SPIN Record Guide: Essential Britpop". Spin. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d Monroe, Jazz (29 March 2017). "The 50 Best Britpop Albums". Pitchfork. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Simon (June 2001). "Walking on Thin Ice". The Wire (209). Archived from the original on 6 November 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ "Radiohead: Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Tucker, Shawn (2013). "The Aesthetics of Dissociation:: Radiohead's "How to Disappear Completely" and Jasper Johns's Device Paintings". Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 96 (1): 85–98. doi:10.5325/soundings.96.1.0085. ISSN 0038-1861. JSTOR 10.5325/soundings.96.1.0085. S2CID 189250854. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ "Radiohead creeps past early success". Billboard. 25 February 1995. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b Power, Ed (12 March 2020). "Why Radiohead's The Bends is the worst great album of all time". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Fake Plastic Trees Lyrics, March 1995, archived from the original on 2 January 2015, retrieved 5 January 2015

- ^ Frere-Jones, Sasha (18 June 2006). "Fine Tuning". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Ross, Alex (12 August 2001). "Becoming Radiohead". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Buxton, Adam (7 July 2013). Colin Greenwood, Jonny Greenwood and Adam Buxton sit in [Jarvis Cocker's Sunday Service BBC Radio 6]. BBC Radio 6. Event occurs at 14:32.

Q: That was a live version of that Magazine track... [Colin Greenwood :] it's a special record for both of us... John McGeoch guitar playing... So I thought it would be nice we could listen to some stuff ... and maybe influence some of what we do... Q: I dont see anyone objecting to Magazine on the Radiohead tour bus ... Have you ever covered any Magazine track ? [Jonny Greenwood:] Sure, we have played "Shot by Both Sides" and we have played the song "Just" which is pretty much the same kind of idea. Q: You were thinking very much Magazine with the angular guitar riffing on "Just", right ? I've been thinking that on most of our kind of angular guitar songs that we do. It's really inventive music.

- ^ Lowe, Steve (December 1999). "Back to save the universe". Select.

- ^ "Iron man". Total Guitar. Future plc. 19 October 2018 – via PressReader.

- ^ Potter, Jordan (31 March 2022). "The Radiohead lyrics edited due to Kurt Cobain's suicide". Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Draper, Brian (11 October 2014). "Chipping Away: Brian Draper Talks to Thom Yorke". Third Way. St. Peters, Sumner Road, Harrow: Third Way Trust, Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Sheffield, Rob (2004). "Radiohead". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 671–72. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Edmonds, Lizzie (25 March 2015). "Stanley Donwood: 'I didn't like Radiohead but they're OK with computers'". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ a b "The surreal story of how the artwork of Radiohead's The Bends was created". Far Out. 2019. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Randall 2000, pp. 98–99.

- ^ "Radiohead creeps past early success". Billboard. 25 February 1995. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Jude (29 September 2024). "'It commemorates collective moments': Radiohead through the eyes of Colin Greenwood". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "ザ・ベンズ/レディオヘッド" [The Bends / Radiohead]. Rockin'On (in Japanese). No. 276. April 1995.

- ^ a b Anon. (2007). "Radiohead — The Bends". In Irvin, Jim; McLear, Colin (eds.). The Mojo Collection (4th ed.). Canongate Books. p. 619. ISBN 978-1-84767-643-6.

- ^ "Radiohead charts". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ Skinner, Tom (27 May 2020). "Radiohead to stream classic Live at the Astoria show in full". NME. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Radiohead streaming 1994 show Live at the Astoria on YouTube: Watch". Consequence of Sound. 28 May 2020. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Footman, Tim (2002). Radiohead: A Visual Documentary. Chrome Dreams. p. 41. ISBN 9781842401798.

- ^ "Billboard 200". Billboard. 13 May 1995. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Billboard 200". Billboard. 24 June 1995. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Billboard 200". Billboard. 17 February 1996. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Billboard 200". Billboard. 20 April 1996. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum – RIAA". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "RIAA Gold and Platinum Searchable Database". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2012. Note: reader must define search parameter as "Radiohead".

- ^ a b Randall, p. 127

- ^ Al, Horner; Twells, John; Lobenfeld, Claire (13 April 2016). "Radiohead on film: The 9 best uses of their songs on screen". Fact. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ a b Dombal, Ryan (21 March 2017). "This is what you get: an oral history of Radiohead's "Karma Police" video". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Q&A: Radiohead's Philip Selway remembers The Bends". Stereogum. 9 March 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "UK Brits Around the World" (PDF). Billboard. 22 February 1997. p. 50. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "BPI Certified Awards Search". British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2012. Note: reader must define search parameter as "The Bends".

- ^ a b Gilbert, Pat (November 1996). "Radiohead". Record Collector.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – The Bends". Irish Singles Chart. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Enriquez, Julio (23 February 2015). "Radiohead's Jonny Greenwood reunited with guitar stolen in Denver in 1995". Denver Post. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ Moran, Caitlin (July 1997). "Everything was just fear". Select: 84.

- ^ Greene, Andy (31 May 2017), "Radiohead's rhapsody in gloom: OK Computer 20 years later", Rolling Stone, archived from the original on 31 May 2017

- ^ a b McKeough, Kevin (27 April 1995). "Radiohead: The Bends (Capitol)". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ Sinclair, Tom (7 April 1995). "The Bends". Entertainment Weekly. No. 269. New York. p. 92. ISSN 1049-0434. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Caroline (17 March 1995). "Radiohead: The Bends (Parlophone)". The Guardian. London. pp. A12–A14. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ^ a b Morris, Sandy (7 May 1995). "Radiohead, 'The Bends,' Capitol". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Radiohead: The Bends". Q. No. 103. London. April 1995.

- ^ Drozdowski, Ted (8 March 1995). "The Bends". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ a b Morrison, Dave (April 1995). "Radiohead: The Bends". Select. No. 58. London.

- ^ a b Eddy, Chuck (May 1995). "Radiohead, 'The Bends' (Capitol)". Spin. Vol. 11, no. 2. New York. pp. 97–98. Archived from the original on 8 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (3 December 1996). "Consumer Guide: Turkey Shoot". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ DiMartino, Dave (2 May 1997). "Give Radiohead to Your Computer". LAUNCH.

- ^ Irvin, Jim (July 1997), "Thom Yorke tells Jim Irvin how OK Computer was done", Mojo

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Bends – Radiohead". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ Modell, Josh (3 April 2009). "Radiohead". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Slaughter, James. "Radiohead: The Bends". Blender. New York. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Radiohead". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ Vozick-Levinson, Simon (11 March 2009). "The Bends: Special Collectors Edition". Entertainment Weekly. New York. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Plagenhoef, Scott (16 April 2009). "Radiohead: Pablo Honey: Collector's Edition / The Bends: Collector's Edition / OK Computer: Collector's Edition". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Segal, Victoria (May 2009). "Radiohead: Pablo Honey / The Bends / OK Computer". Q. No. 274. London. pp. 120–21.

- ^ Edwards, Gavin (11 March 2003). "The Bends". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ Richards, Sam (8 April 2009). "Radiohead Reissues – Collectors Editions". Uncut. London. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Sullivan, Caroline (May 1997). "Aching Heads". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ Runtagh, Jordan (22 February 2018). "Radiohead's Pablo Honey: 10 things you didn't know". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Hornby, Nick (22 October 2000). "Radiohead Gets Farther Out". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Kleinedler, Clare (23 March 2009). "A 1996 Radiohead Interview – The Bends, Britpop And OK Computer". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ "The 50 albums that changed music". The Observer. 16 July 2006. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Plagenhoef, Scott (16 August 2006). "Thom Yorke". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Beatles, Radiohead albums voted best ever", CNN.com, 4 September 2000, archived from the original on 22 May 2008, retrieved 8 October 2008

- ^ "Q Readers All Time Top 100 Albums". Q. No. 137. February 1998.

- ^ "Q Magazine's Q Readers Best Albums Ever (2006 Readers Poll) Archived by Lists of Bests". Q. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ Larkin, Colin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (7 February 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "500 Best Albums of All Time". Penske Media Core. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ "Oasis album voted greatest of all time". The Times. 1 June 2006. Archived from the original on 8 April 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ Jackson, Josh (24 February 2012). "The 90 Best Albums of the 1990s". Paste. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Ross, Graeme (13 March 2020). "The 20 best albums of 1995 ranked". The Independent. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ a b Nestruck, Kelly (8 November 2007). "EMI stab Radiohead in the back catalogue". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ McCarthy, Sean (18 December 2009). "The Best Re-Issues of 2009: 18: Radiohead: Pablo Honey / The Bends / OK Computer / Kid A / Amnesiac / Hail to the Thief". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 20 December 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ McCarthy, Sean (18 December 2009). "The Best Re-Issues of 2009: 18: Radiohead: Pablo Honey / The Bends / OK Computer / Kid A / Amnesiac / Hail to the Thief". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 20 December 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Knopper, Steve (8 February 2013). "Pink Floyd, Radiohead Catalogs Change Label Hands". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ Christman, Ed (4 April 2016). "Radiohead's Early Catalog Moves From Warner Bros. to XL". Billboard. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Spice, Anton (6 May 2016). "Radiohead to reissue entire catalogue on vinyl". The Vinyl Factory. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ The Bends (album liner notes). Radiohead. Parlophone. 1995.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Australiancharts.com – Radiohead – The Bends". Hung Medien.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Radiohead – The Bends" (in German). Hung Medien.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Radiohead – The Bends" (in Dutch). Hung Medien.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Radiohead – The Bends" (in French). Hung Medien.

- ^ "HITS OF THE WORLD". Billboard. 30 March 1996. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Radiohead – The Bends" (in Dutch). Hung Medien.

- ^ "Eurochart Top 100 Albums - February 17, 1996" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 13, no. 7. 17 February 1996. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Radiohead – The Bends" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Radiohead – The Bends". Hung Medien.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Radiohead – The Bends". Hung Medien.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company.

- ^ "Radiohead Chart History: Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1995". The Official NZ Music Charts. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 1995". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1996". dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Year End Sales Charts – European Top 100 Albums 1996" (PDF). Music & Media. 21 December 1996. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1996". The Official NZ Music Charts. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 1996". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 1996". Ultratop. Hung Medien.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Radiohead – The Bends". Music Canada.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Radiohead – The Bends" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 15 November 2021. Select "2021" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "The Bends" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – Radiohead – The Bends" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Enter The Bends in the "Artiest of titel" box. Select 1997 in the drop-down menu saying "Alle jaargangen".

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Radiohead – The Bends". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ Jones, Alan (13 May 2016). "Official Charts Analysis: Drake holds off competition from Calvin Harris and Justin Timberlake". Music Week. Intent Media. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "British album certifications – Radiohead – The Bends". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "Radiohead's Digital Album Sales, Visualized". Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "American album certifications – Radiohead – The Bends". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 2001". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

Bibliography

- Randall, Mac (2000). Exit Music: The Radiohead Story. Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-7977-4.

- Randall, Mac (2004). Exit Music: The Radiohead Story. Omnibus. ISBN 1-84449-183-8.

- Randall, Mac (1 February 2012). Exit Music: The Radiohead Story Updated Edition. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4584-7147-5.

External links

edit- The Bends at Discogs (list of releases)

- Album online on Spotify, a music streaming service

- The Bends at MusicBrainz (list of releases)