Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport (IATA: CVG, ICAO: KCVG, FAA LID: CVG) is a public international airport located in Boone County, Kentucky, United States, around the community of Hebron. The airport serves the Cincinnati tri-state area. The airport's code, CVG, is derived from the nearest city at the time of the airport's opening, Covington, Kentucky. The airport covers an area of 7,000 acres (10.9 sq mi; 28.3 km2).[3][4] It is included in the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems for 2023–2027, in which it is categorized as a medium-hub primary commercial service facility.[5]

Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner/Operator | CVG Airport Authority (formerly Kenton County Airport Board) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Cincinnati metropolitan area | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | 2939 Terminal Drive Boone County, Kentucky, U.S. (Hebron postal address) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | January 10, 1947[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating base for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 896 ft / 273 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 39°02′56″N 084°40′04″W / 39.04889°N 84.66778°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||

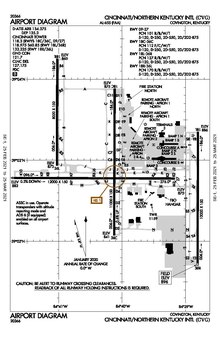

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2023) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: CVG Airport[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport offers non-stop passenger service to over 50 destinations in North America and Europe,[6] handling numerous domestic and international cargo flights every day.[7] The airport is a cargo global hub for Amazon Air, Atlas Air, ABX Air, Kalitta Air, and DHL Aviation. The airport is currently the 6th busiest airport in the United States by cargo traffic and 12th largest in the world. CVG is the fastest-growing cargo airport in North America.[8][9]

History

editBeginnings

editPresident Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration approved preliminary funds for site development of the Greater Cincinnati Airport on February 11, 1942. This was part of the United States Army Air Corps program to establish training facilities during World War II. At the time, air traffic in the area centered on Lunken Airport just southeast of central Cincinnati.[10] Lunken opened in 1926 in the Ohio River Valley; it frequently experienced fog, and the 1937 flood submerged its runways and two-story terminal building.[11] Federal officials wanted an airfield site that would not be prone to flooding, but Cincinnati officials hoped to build Lunken into the region's main airport.[12]

Officials from Boone, Kenton, and Campbell counties in Kentucky took advantage of Cincinnati's short-sightedness and lobbied Congress to build an airfield there.[13] Boone County officials offered a suitable site on the provision that Kenton County paid the acquisition cost. In October 1942, Congress provided $2 million to build four runways.[10]

The field opened August 12, 1944, with the first B-17 bombers beginning practice runs on August 15. As the tide of the war had already turned, the Air Corps only used the field until it was declared surplus in 1945.[10] However, this was not before the first regularly scheduled air freight shipment in the United States arrived in mid-September, signalling the future importance of the airport.[14]

On October 27, 1946, a small wooden terminal building opened and the airport prepared for commercial service under the name Greater Cincinnati Airport. Boone County Airlines was the first airline to provide scheduled service from the airport and had its headquarters at the airport.[10][a]

The first commercial flight, an American Airlines DC-3 from Cleveland, landed on January 10, 1947, at 9:53 am. A Delta Air Lines flight followed moments later.[16] The April 1957 Official Airline Guide shows 97 weekday departures: 37 American, 26 Delta, 24 TWA, 8 Piedmont, and 2 Lake Central. As late as November 1959 the airport had four 5,500 ft (1,700 m) runways at 45-degree angles, the north–south runway eventually being extended into today's runway 18C/36C.

In the 1950s Cincinnati city leaders began pushing for expansion of a site in Blue Ash to both compete with the Greater Cincinnati Airport and replace Lunken as the city's primary airport.[17] The city purchased Hugh Watson Field in 1955, turning it into Blue Ash Airport.[18] The city's Blue Ash plans were hampered by community opposition, three failed Hamilton County bond measures,[19] political infighting,[20] and Cincinnati's decision not to participate in the federal airfield program.[21]

Jet age

editOn December 16, 1960, the jet age arrived in Cincinnati when a Delta Air Lines Convair 880 from Miami completed the first scheduled jet flight. The airport needed to expand and build more modern terminals and other facilities; the original Terminal A was expanded and renovated. The north–south runway was extended from 3,100 to 8,600 ft (940 to 2,620 m). In 1964, the board approved a $12 million bond to expand the south concourse of Terminal A by 32,000 sq ft (3,000 m2) and provide nine gates for TWA, American, and Delta.[10] A new east–west runway crossing the longer north–south runway was constructed in 1971 south of the older east–west runway.

In 1977, before the Airline Deregulation Act was passed, CVG, like many small airports, anticipated the loss of numerous flights; creating the opportunity for Patrick Sowers, Robert Tranter, and David and Raymound Mueller to establish Comair to fill the void. The airline began service to Akron/Canton, Cleveland, and Evansville. In 1981, Comair became a public company, added 30-seat turboprops to its fleet, and began to rapidly expand its destinations. In 1984, Comair became a Delta Connection carrier with Delta's establishment of a hub at CVG. That same year, Comair introduced its first international flights from Cincinnati to Toronto. In 1992, Comair moved into Concourse C, as Delta Air Lines gradually continued to acquire more of the airline's stock. In 1993, Comair was the launch customer for the Canadair Regional Jet, of which it would later operate the largest fleet in the world. By 1999, Comair was the largest regional airline in the country worth over $2 billion, transporting 6 million passengers yearly to 83 destinations on 101 aircraft. Later that year, Delta Air Lines acquired the remaining portion of Comair's stock, causing Comair to solely operate Delta Connection flights.[22]

In 1988, two founders of Comair, Patrick Sowers and Robert Tranter launched a new scheduled airline from CVG named Enterprise Airlines, which served 16 cities at its peak. The airline spearheaded the regional jet revolution in a unique manner by operating 10-seat Cessna Citation business jets in scheduled services. The flights became popular with Cincinnati companies. The airline served destinations including Baltimore, Boston, Cedar Rapids, Columbus (OH), Green Bay, Greensboro, Greenville, Hartford, Memphis, Milwaukee, New York–JFK, and Wilmington (NC).[23] The airline also became the first international feed carrier by feeding the British Airways Concorde at JFK. In 1991, the airline ceased operations because of high fuel prices and the suspension of the British Airways contract after the first Gulf War.

Delta Air Lines hub

editIn the mid-1980s, Delta opened a hub in Cincinnati and constructed Terminals C and D with 22 gates. During the decade, Delta ramped up both mainline and Comair operations and established Delta Connection. Delta's continued growth at CVG then prompted them to spend $550 million to build their own terminal facility in the 1990s.[24] The new terminal, known then as Terminal 3, opened in 1994 and would largely replace Terminal D. Terminal 3 consisted of three airside concourses, with most of Terminal D's gate space being repurposed into Terminal 3's Concourse A while Concourses B and C were new construction. Concourses A and B were parallel concourses connected to Terminal 3's main building by an underground walkway which also included a people mover (a similar layout to Delta's main hub at Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport). Concourse C was only accessible by shuttle buses and was a ground-level facility for regional aircraft used by Delta Connection (operated by Comair). After the opening of Terminal 3, the former Terminals B and C were renamed Terminals 1 and 2 respectively, which continued to house non-Delta airlines.[25]

Aircraft operations dramatically increased from around 300,000 to 500,000 yearly aircraft movements. In turn, passenger volumes doubled within a decade from 10 million to over 20 million. This expansion prompted the building of runway 18L/36R and the airport began making preparations to construct Concourse D while adding an expansion to Concourse A and B.[26]

At its peak, CVG became Delta's second largest hub, handling over 600 flights daily in 2005.[27] It was the fourth largest hub in the world for a single airline, based on departures, ranking only behind Atlanta, Chicago–O'Hare, and Dallas/Fort Worth.[28] The hub served everything from a 64-mile flight to Dayton, to a daily nonstop to Honolulu and Anchorage, to transatlantic destinations including Amsterdam, Brussels, Frankfurt, London, Manchester, Munich, Paris, Rome, and Zürich.[29] Additionally, Air France operated flights into CVG for several periods for over a decade before finally terminating the service in 2007.[30][31]

When Delta went into bankruptcy in September 2005, a large reduction at CVG eliminated most early-morning and night flights.[29] These initial cuts caused additional routes to become unprofitable, causing the frequency of low-volume routes to be further cut from 2006 to 2007. Planning for the new east–west runway stopped, along with all expansions to current terminals; Terminal 1 was closed due to lack of service. In 2008, Delta merged with Northwest Airlines and cut flight capacity from the Cincinnati hub by 22 percent with an additional 17 percent reduction in 2009.[27] Concourse C, opened in 1994 at a cost of $50 million, was permanently closed in 2008 and demolished in 2016.[32] Further reductions in early 2010 caused Delta to close Concourse A in Terminal 3 on May 1, consolidating all operations into Concourse B. This resulted in the layoff of more than 800 employees.[33]

By 2011, Delta was down to roughly 130 flights per day at CVG.[34] After several years of cuts to its older fleet, which were cited as being cut due to high costs associated with rising oil prices, Delta's wholly-owned and CVG-based subsidiary, Comair, ceased all operations in September 2012, ending over three decades of operations.[35] In 2017, the hub was downgraded to a focus city, which was eliminated in 2021.[36]

Recent history

editUntil 2015, CVG consistently ranked among the most expensive major airports in the United States.[37] Delta operated over 75% of flights at CVG, a fact often cited as a reason for relatively high domestic ticket prices.[38] Airline officials suggested that Delta was practicing predatory pricing to drive away discount airlines.[37][39] From 1990 to 2003, ten discount airlines began service at CVG, but later pulled out,[40] including Vanguard Airlines, which pulled out of CVG twice.[41] After Delta downsized its hub operations, low cost carriers began operations and have been sustained at the airport ever since.[42][43]

Terminal 2 was closed in May 2012, and CVG re-opened and consolidated all non-Delta airlines to Concourse A in Terminal 3 at that time, which became the sole terminal.[44] Renovation and expansion of the ticketing/check-in area and Concourse A took place that year to accommodate the move.[45][46] Terminals 1 and 2 were torn down in early 2017 to construct an overnight parking and deicing area.[47] Both concourses, the customs facility, baggage claim, and ticketing areas were renovated in late 2017 to mid 2018 under a $4.5 million plan.[48][49] In 2021, the airport opened a new rental car and ground transportation center adjacent to the main terminal.[50]

Location

editThe airport is in an unincorporated area of the county.[51] Various articles of the Cincinnati Enquirer describe the airport as being in Hebron.[52][53] The airport terminal uses a Hebron postal address, while the administrative headquarters uses an Erlanger postal address.[54] The airport is outside of the Hebron census-designated place, which is defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, and the airport is also not in Erlanger, a city.[51]

The office, at 77 Comair Boulevard, was formerly the headquarters of the American regional airline Comair.[55]

Facilities

editTerminal

editThe airport has one terminal and two concourses with a total of 51 gates.[56] Both concourses are islands and are only accessible by an underground moving walkway and people mover.[57] All international arrivals without pre-clearance are handled in Concourse B.[57]

Art

editThe airport is home to 14 large Art Deco murals created for the train concourse building at Cincinnati Union Terminal during the station's construction in 1932. Mosaic murals depicting people at work in local Cincinnati workplaces were incorporated into the interior design of the railroad station by Winold Reiss, a German-born artist with a reputation in interior design. When the train concourse building was designated for demolition in 1972, a "Save the Terminal Committee" raised funds to remove and transport the 14 murals in the concourse to new locations in the Airport. They were placed in Terminal 1, as well as Terminals 2 and 3, which were then being constructed as part of major airport expansion and renovation. When Terminals 1 and 2 were demolished, the murals in those areas were stored and the new Security Screening building was designed to accommodate the heavy weight of the murals with the eastern "store front" windows designed to be removable to permit the future installation of the murals. The murals were also featured in a scene in the film Rain Man starring Dustin Hoffman and Tom Cruise. In addition, a walkway to one of the terminals at CVG was featured in the scene in the film when Hoffman's character, Raymond, refused to fly on a plane. The nine murals located in the former Terminals 1 & 2 were relocated to the Duke Energy Convention Center in downtown Cincinnati.[58]

Additionally, there are several pieces of Charley Harper artwork in the Concourse B food court.

Cargo hubs

editIn 1984, DHL opened its CVG hub and began operations throughout the world. However, in 2004, DHL decided to move its hub to Wilmington, Ohio, in order to compete in the United States shipment business.[clarify] The plan ended up failing, and DHL moved back to CVG in 2009 to resume its original operations. CVG now serves as the largest of DHL's three global hubs (the other two being Leipzig/Halle and Hong Kong) with numerous flights each day to destinations across North America, Europe, Middle East, Asia, and the Pacific.[citation needed] DHL has completed a $105 million expansion and employs approximately 2,500 at CVG. Because of this growth, CVG stood as the 4th busiest airport in North America based on cargo tonnage and 34th in the world at the time.[59]

On May 28, 2015, DHL announced a $108M expansion to its current facility, which doubled the current cargo operations. The money was used to double the gate capacity for transferring cargo, an expansion to the sorting facility, and various technical improvements, which was completed in Autumn 2016. In addition, this has provided many more jobs for the Cincinnati area, and will dramatically increase the airport's operations.[60][61]

On January 31, 2017, Amazon announced that its new cargo airline, Amazon Air would pick CVG as its main worldwide shipping hub, following an investment of $1.49B in the construction and expansion of a cargo facility on the airport grounds.[62] The company used DHL's facilities prior to the construction of its new facility. The hub is Amazon's principal shipping hub and was constructed on 1,129 acres (457 ha) of land at the airport with a 3,000,000 sq ft (280,000 m2) sorting facility and parking positions for over 100 aircraft. On April 30, 2017, Amazon began operations at CVG with 75 Boeing 767-200ER/300ER aircraft based at the airport and planned to have 200 daily takeoffs and landings from its CVG hub to destinations across the U.S. and internationally.[63] The hub could create up to 15,000 jobs in the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky region.[64] On August 11, 2021, Amazon debuted its new cargo hub at CVG. On May 28, 2024, Atlas announced that "Atlas Air has successfully reached an agreement to fully exit their Amazon CMI operations, which no longer aligned with our company plans. Separately, through Titan, we are pleased to extend the dry leasing portion of our relationship with Amazon."[citation needed]

Ground transportation

editThe TANK 2X bus provides daily service in to downtown Cincinnati.[65]

Airlines and destinations

editPassenger

editCargo

editStatistics

editTop destinations

edit| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atlanta, Georgia | 418,000 | Delta, Frontier |

| 2 | Orlando, Florida | 272,000 | Delta, Frontier, Southwest |

| 3 | Denver, Colorado | 269,000 | Allegiant, Delta, Frontier, Southwest, United |

| 4 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 263,000 | American, Frontier |

| 5 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 218,000 | American, United |

| 6 | Charlotte, North Carolina | 193,000 | American, Frontier |

| 7 | Newark, New Jersey | 141,000 | Allegiant, Delta, United |

| 8 | Tampa, Florida | 144,000 | Delta, Frontier |

| 9 | New York–LaGuardia, New York | 137,000 | American, Delta, Frontier |

| 10 | Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota | 135,000 | Delta, Frontier, Sun Country |

| Rank | City | Cargo (pounds) | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anchorage, Alaska | 38,686,878 | AirBridgeCargo, DHL |

| 2 | Leipzig/Halle, Germany | 14,447,211 | AirBridgeCargo, DHL |

| 3 | Miami, Florida | 14,427,248 | Amazon, American, DHL |

| 4 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 10,341,326 | Amazon, American, Delta, DHL, United |

| 5 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 8,819,609 | Amazon, American, Delta, DHL |

| 6 | Phoenix–Sky Harbor, Arizona | 8,431,588 | Amazon, Delta, DHL |

| 7 | Brussels, Belgium | 8,223,096 | AirBridgeCargo, DHL |

| 8 | Guadalajara, Mexico | 7,990,928 | AeroUnion, Cargojet, DHL |

| 9 | Houston, Texas | 7,066,885 | Amazon, Delta, DHL, United |

Airline market share

edit| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Delta Air Lines | 2,053,000 | 23.59% |

| 2 | Frontier Airlines | 1,359,000 | 15.61% |

| 3 | Allegiant Air | 956,000 | 10.98% |

| 4 | American Airlines | 844,000 | 9.70% |

| 5 | Endeavor Air | 818,000 | 9.40% |

Annual traffic

editGraphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 11,545,682 | 2002 | 20,812,642 | 2012 | 6,038,817 | 2022 | 7,573,416 |

| 1993 | 12,213,874 | 2003 | 21,197,447 | 2013 | 5,718,255 | 2023 | 8,718,443 |

| 1994 | 13,593,522 | 2004 | 22,062,557 | 2014 | 5,908,711 | 2024 | 6,988,090 (YTD) |

| 1995 | 15,181,728 | 2005 | 22,778,785 | 2015 | 6,316,332 | 2025 | |

| 1996 | 18,795,766 | 2006 | 16,244,962 | 2016 | 6,773,905 | 2026 | |

| 1997 | 19,866,308 | 2007 | 15,736,220 | 2017 | 7,842,149 | 2027 | |

| 1998 | 21,124,216 | 2008 | 13,630,443 | 2018 | 8,865,568 | 2028 | |

| 1999 | 21,753,512 | 2009 | 10,621,655 | 2019 | 9,103,554 | 2029 | |

| 2000 | 22,406,384 | 2010 | 7,977,588 | 2020 | 3,615,139 | 2030 | |

| 2001 | 17,270,475 | 2011 | 7,034,263 | 2021 | 6,282,253 | 2031 |

Accidents and incidents

edit- On January 12, 1955, 1955 Cincinnati mid-air collision, a Martin 2-0-2 was in the take off phase of departure from the airport when it collided with a privately owned Castleton Farm DC-3. The mid-air collision killed 13 people on the commercial airliner and two on the privately owned plane.[94][95]

- On November 14, 1961, Zantop cargo flight, a DC-4, crashed near runway 18 into an apple orchard. The crew survived.[96]

- On November 8, 1965, American Airlines Flight 383, a Boeing 727, crashed on approach to runway 18C, killing 58 (53 passengers and five crew) of the 62 (56 passengers and six crew) on board.[97]

- On November 6, 1967, TWA Flight 159, a Boeing 707, overran the runway during an aborted takeoff, injuring 11 of the 29 passengers. One of the injured passengers died four days later. The seven crew members were unhurt.[98]

- On November 20, 1967, TWA Flight 128, a Convair 880, crashed on approach to runway 18, killing 70 (65 passengers and five crew) of the 82 persons aboard (75 passengers and seven crew).[99]

- On October 8, 1979, Comair Flight 444, a Piper Navajo, crashed shortly after takeoff. Seven passengers and the pilot were killed.[100]

- On October 19, 1979, Burlington Airways, a Beechcraft Model 18 crash landed on KY 237 at the I-275 bridge overpass. There were no injures.[101]

- On June 2, 1983, Air Canada Flight 797, a DC-9 flying on the Dallas-Toronto-Montreal route, made an emergency landing at Cincinnati due to a cabin fire. 23 of the 41 passengers died of smoke inhalation or fire burns, including folk singer Stan Rogers. All five crew members survived.[102]

- On August 13, 2004, Air Tahoma Flight 185, a Convair 580, was en route to Cincinnati from Memphis, Tennessee, carrying freight under contract for DHL Worldwide Express. The aircraft crashed on a golf course just south of the Cincinnati airport due to fuel starvation and dual engine failure, killing the first officer and injuring the captain.[103]

See also

editReferences

editThis article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

Footnotes

editNotes

edit- ^ "CVG Airport Marks 75th Anniversary with Year-Long Celebration". cvgairport.com. CVG Leadership. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "2022 CVG Air Traffic Stats" (PDF). cvgairport.com.

- ^ FAA Airport Form 5010 for CVG PDF Effective November 28, 2024

- ^ "CVG Airport Data at SkyVector". skyvector.com. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "NPIAS Report 2023-2027 Appendix A" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. October 6, 2022. p. 54. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "CVG Fact Sheet October 2020" (PDF). Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "Amazon, DHL key in new CVG strategy to land development". Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Cincinnati, OH: Cincinnati/ Northern Kentucky International (CVG)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. May 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- ^ "Launching Point 2017: A Year in Review" (PDF). Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Detailed History". cvgairport.com. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Stulz, Larry (February 14, 2008). "Lunken Airport". Cincinnati-Transit.net.

- ^ Steve Kemme (December 28, 2010). "Flood sank Lunken plans". Cincinnati Enquirer-Our History. Cincinnati.com. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ "MTM Cincinnati: Why Is Cincinnati Airport In Kentucky?". Edged in Blue. 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Aerial Freight Skips Lunken in Fog, Lands at Kenton". Cincinnati Post. 15 September 1944. p. 30.

- ^ "Commercial Airline Service is Inaugurated at Kenton County's Greater Cincinnati Port". Cincinnati Enquirer. 9 March 1945. p. 2. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Donna M. DeBlasio; John Johnston (July 31, 1999). "Cincinnati's Century of Change: Timeline". The Cincinnati Enquirer. enquirer.com. p. S3. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Gale, Oliver (November 1993). "On the Waterfront". Cincinnati Magazine. 27 (2). CM Media: 75–76. ISSN 0746-8210.

- ^ Rose, Mary Lou (March 22, 2012). "Letter to the Editor: History of Blue Ash Airport is important". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Renaissance in '70s led to place among 'Fab 50'". Cincinnati.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008.

- ^ Wessels, Joe (October 26, 2006). "Council votes to sell airport land". The Cincinnati Post. p. A2.

Cincinnati City Council voted 8-1 Wednesday for an agreement to sell 128 acres of the approximately 230-acre airport to the city of Blue Ash.... The city of Cincinnati purchased the airport, located six air miles northeast of Cincinnati, in 1946 from a private company that had been using it as an airfield since 1921. Cincinnati officials intended to use the land to build a new commercial airport after 1937 Flood completely submerged Lunken Field in the East End, then the only airport with commercial flights in the area. A series of failed bond issues and political infighting – and Northern Kentucky politicians' successes at securing federal funding – wound up with the region's major airport being developed in Boone County.

- ^ "From Humble Beginnings... to an International Hub". Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. December 12, 2012. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Nonstop Performance Since 1977". Departed Flights. Comair. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ "Enterprise Airlines". Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "The Death and Rebirth of Memphis (MEM) and Cincinnati (CVG)". AirlineGeeks. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Cincinnati/Northern KentuckyInternational Airport (CVG)". Cincinnati Transit. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "CVG 2025 Master Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b Kelly Yamanouchi (August 2, 2009). "Cincinnati hub is shrinking". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ajc.com. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ "New Delta hub plan in wings". Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Why CVG lost half of all flights". Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- ^ "Air France Suspends Paris Flight". The Cincinnati Post. June 8, 2001. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ "Air France Starts New Daily Service in Cincinnati". Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Jason Williams (March 4, 2016). "CVG saying goodbye to Concourse C". Cincinnati Enquirer. cincinnati.com.

- ^ "Delta further reduces operations at Cincinnati hub; 840 face layoffs". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Associated Press. March 16, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Yamanouchi, Kelly. "Hub changes hit Cincinnati hard". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution – via AJC.com.

- ^ "Comair to Cease Operations". July 27, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ "Delta kills CVG's 'focus city' status". Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ a b Coolidge, Alexander (January 3, 2007). "Cincinnati's sky-high airfares are tops in the USA". The Cincinnati Enquirer. p. A8. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Rose, Marla Matzer (January 27, 2008). "Governors push to keep Delta hub". The Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Paul Barton (December 20, 1999). "High air fares getting attention". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Cincinnati.com. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Pilcher, James (November 23, 2003). "Curse of high fares has economic upside". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Duke, Kerry (November 30, 2006). "Discount Airline Passes on CVG". The Kentucky Post. p. A1. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Jason (July 23, 2015). "Allegiant Air makes CVG a home, creates jobs". Allegiant Air makes CVG a home, creates jobs. Cincinnati.com. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ "CVG doesn't suck anymore. How did that happen?". 3 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ "Ground Control". May 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ "CVG's new Concourse A: SLIDESHOW". www.bizjournals.com. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ Wells, Dan (14 May 2012). "Newly renovated CVG concourse A opens". www.fox19.com. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ "CVG to demolish Concourse". Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "CVG plans multimillion-dollar upgrade". Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ "Master Plan Report" (PDF). cvgairport.com. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- ^ "CVG opens new rental car and ground transportation center". 20 October 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b "2020 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Boone County, KY" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 6 (PDF p. 7/15). Retrieved 2023-08-08.

Cincinnati/northern Kentucky International Arprt

- See also: Map of the Hebron CDP - ^ "Travel slows at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport". Cincinnati Enquirer. 2020-03-18. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- ^ "A look inside the Amazon Air Hub at CVG". The Enquirer. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ "Contact". Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

Terminal Location: 3087 Terminal Drive, Hebron, KY 41048 [...] Office Location: 77 Comair Blvd, Erlanger, KY 41018

- ^ "CVG board approves lease deal for Southern Air." Business Courier. Tuesday July 17, 2012. Retrieved on July 30, 2012. "[...]77 Comair Blvd.[...]to the building that formerly housed Comair’s headquarters."

- ^ a b c "CVG Terminal Map". Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Step by Step Directions". Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ "Long hidden at CVG, murals closer to coming home". Cincinnati.com. May 19, 2015.

- ^ "stats" (PDF). cvgairport.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-12. Retrieved 2014-09-25.

- ^ DeMio, Terry. "DHL to expand at CVG due to e-commerce growth". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ "RITA | BTS | Transtats". Transtats.bts.gov. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Amazon adds 200 ac for its CVG air hub". Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "Amazon to create $1.5B air hub at CVG". Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ "Experts: Amazon Prime Air could bring up to 15K jobs over time". 3 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ 2X Airporter

- ^ "Airline launching new international route out of CVG Airport". WLWT. September 12, 2024.

- ^ "Flight Schedules". Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "Alaska Airlines - Route Map". Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Allegiant Ties Record for Largest Expansion in Company History with 44 New Nonstop Routes, plus 3 New Cities". Allegiant Air (Press release). November 19, 2024. Retrieved November 19, 2024 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ "Allegiant Air - Route Map". Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Flight schedules and notifications". Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Timetables". British Airways. London: International Airlines Group.

- ^ "Where We Fly - Delta Air Lines". Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Frontier Airlines 1Q25 Various Network Resumptions". Aeroroutes. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ "Frontier Airlines Announces 22 New Routes Launching in December".

- ^ "Frontier". Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "Check Flight Schedules". Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "Sun Country - Route Map". Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Timetable". Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "Mexican ULCC, Viva Aerobus, announces its new nonstop service between Cincinnati and Los Cabos (Mexico)". www.cvgairport.com.

- ^ Jay, Tim (November 30, 2022). "Amazon Air begins daily cargo service at Manchester-Boston Regional Airport". Global Trade Magazine. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "Fleet and Bases". ameriflight.com. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Atlas Air Schedule". Atlas Air. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ^ "Flight Activity History (CSJ915)". Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Martinez, Lourdes (28 February 2023). "The company DHL began cargo operations at AIFA". adn40 (in Spanish). TV Azteca, S.A.B. de C.V. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "DHL Express apre il volo diretto Milano Malpensa – Cincinnati. E' un volo per l'esportazione del Made in Italy" [DHL Express begins direct flight Milan Malpensa-Cincinnati. It's a flight for Made in Italy export]. italiavola.com (in Italian). 17 November 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Changi Airport Freight Arrivals". Changi Airport Freight Arrivals. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ "FedEx (FX) #701 ✈ FlightAware". Flightaware.com. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ "FedEx (FX) #1260 ✈ FlightAware". flightaware.com. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ "Cincinnati, OH: Cincinnati/ Northern Kentucky International (CVG)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. January 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "Cincinnati, OH: Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International (CVG)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ "CVG 2025 Master Plan" (PDF). cvgairport.com. CVG Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "News & Stats". Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ "Accident description for N93211 at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Accident description for N999B at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Accident description for N30061 at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Accident description for N1996 at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Accident description for N742TW at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Accident description for N821TW at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Accident description for N6642L at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Iad80Flq04". www.ntsb.gov. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012.

- ^ "Accident description for C-FTLU at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Accident description for N586P at Aviation Safety Network". aviationsafetynetwork.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

External links

edit- Media related to Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport at Wikimedia Commons

- Historical Images of Cincinnati-Northern Kentucky Airport

- History of the Industrial Murals Archived 2022-05-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Mural images and location map

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective November 28, 2024

- FAA Terminal Procedures for CVG, effective November 28, 2024

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KCVG

- ASN accident history for CVG

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KCVG

- FAA current CVG delay information