Caffeine dependence is a condition characterized by a set of criteria, including tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to control use, and continued use despite knowledge of adverse consequences attributed to caffeine.[1] It can appear in physical dependence or psychological dependence, or both. Caffeine is one of the most common additives in many consumer products, including pills and beverages such as caffeinated alcoholic beverages, energy drinks, pain reliever medications, and colas. Caffeine is found naturally in various plants such as coffee and tea. Studies have found that 89 percent of adults in the U.S. consume on average 200 mg of caffeine daily.[2] One area of concern that has been presented is the relationship between pregnancy and caffeine consumption. Repeated caffeine doses of 100 mg appeared to result in smaller size at birth in newborns. When looking at birth weight however, caffeine consumption did not appear to make an impact.[3]

| Caffeine dependence | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Caffeine addiction |

| |

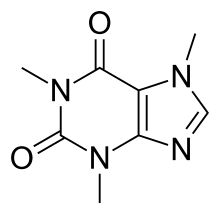

| Molecular structure of caffeine | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Dependence vs. addiction

editModerate physical dependence often arises from prolonged long-term caffeine use.[4] In the human body, caffeine blocks adenosine receptors A1 and A2A.[5] Adenosine is a by-product of cellular activity: the stimulation of adenosine receptors produces feelings of tiredness and a drive for sleep. Caffeine's ability to block these receptors means the levels of the body's natural stimulants, dopamine and norepinephrine, continue at higher levels.

Continued exposure to caffeine prompts the body to create more adenosine-receptors in the central nervous system, which increases the body's adenosine sensitivity. This reduces the stimulatory effects of caffeine by increasing tolerance. It also causes the body to suffer withdrawal symptoms (such as headaches, fatigue, and irritability) if caffeine intake decreases.[6]

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders describes four caffeine-related disorders including intoxication, withdrawal, anxiety, and sleep.[7]

Pathologically reinforced caffeine use induces a dependence syndrome, but not an addiction.[8] For a drug to induce an addiction from repeated use at sufficiently high doses, it must activate the brain's reward circuitry, particularly the mesolimbic pathway.[8] Neuroimaging studies of preclinical and human subjects have demonstrated that chronic caffeine consumption does not sufficiently activate the reward system, relative to other drugs of addiction (e.g., cocaine, morphine, nicotine).[9][10][11] As a consequence, compulsive use (i.e., an addiction) of caffeine has yet to be observed in humans.[8] Caffeine dependence forms due to caffeine antagonizing the adenosine A2A receptor,[12] effectively blocking adenosine from the adenosine receptor site. This delays the onset of drowsiness and releases dopamine.[13] As of right now, caffeine withdrawal qualifies as a psychiatric condition by the American Psychiatric Association, but caffeine-use disorder does not.[14]

Professor Roland R. Griffiths, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, strongly believes that caffeine withdrawal should be classified as a psychological disorder.[15] His research suggests that withdrawal affects 50% of habitual coffee drinkers, beginning within 12–24 hours after cessation of caffeine intake, and peaking in 20–48 hours, lasting as long as 9 days.[16][17] In another study, he concluded that people who take in a minimum of 100 mg of caffeine per day (about the amount in one cup of coffee) can acquire a physical dependence that would trigger withdrawal symptoms, including muscle pain and stiffness, nausea, vomiting, depressed mood, and other symptoms.[15][6]

Physiological effects

editCaffeine dependence can cause a host of physiological effects if caffeine consumption is not maintained. Commonly known caffeine withdrawal symptoms include headaches, fatigue, loss of focus, lack of motivation, mood swings, nausea, insomnia, dizziness, cardiac issues, hypertension, anxiety, and backache and joint pain; these can range in severity from mild to severe.[18] These symptoms may occur within 12–24 hours and can last two to nine days.[19][20][21]

Tests are still being done to get a better understanding of the effects that occur when people become dependent on different forms of caffeine to make it through the day. There has been research findings that suggest that the circadian cycle is not significantly changed under popular practices of caffeine consumption in the morning and during the afternoon.[22]

Children and teenagers

editAccording to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), it is not recommended for individuals under the age of 18 to consume several caffeinated drinks in one day.[23] Failure to restrict caffeine intake can lead to side effects such as increase in heart rate and blood pressure, sleep disturbance, mood swings, and acid reflux.; caffeine's lasting effects on children's nervous and cardiovascular systems are currently unknown. Some research has suggested that caffeinated drinks should not be advertised to children as a primary audience.[24][25]

Pregnancy

editIf pregnant, it is recommended not to consume more than 200 mg of caffeine a day (though this is relative to the pregnant woman's weight).[26] If a pregnant woman consumes high levels of caffeine, it can result in low birth weight due to loss of blood flow to the placenta,[27] and could lead to health problems later in the child's life.[28] It can also result in premature labor, reduced fertility, and other reproductive issues. The American Pregnancy Association suggests "avoiding caffeine as much as possible" before and during pregnancy or discussing how to curtail dependency with a healthcare provider.[29]

Treatment

editUnderstanding effective treatment strategies is crucial in managing caffeine dependence, a condition that has garnered increasing attention in recent years. A plethora of studies have surfaced aimed at reducing caffeine intake and alleviating withdrawal symptoms. One significant contribution comes from a comprehensive review and research agenda that undertook a thorough examination of caffeine use disorder.[20] This review not only discusses potential diagnostic criteria but also highlights the far-reaching implications for individuals struggling with caffeine dependency. The author characterizes caffeine as a widely consumed substance, yet one that is not immune to fostering dependency. Despite its generally recognized safety profile, clinical evidence suggests a concerning trend wherein users develop a reliance on caffeine, often struggling to curtail consumption despite recurring health concerns, such as cardiovascular issues and perinatal complications.[30]

Evidence-based treatment strategies offer hope for individuals seeking to break free from caffeine dependency. These strategies encompass a spectrum of approaches, including dose tapering, intermittent fasting, diligent monitoring of caffeine intake through journaling, and the incorporation of regular exercise coupled with professional counseling.[20]

Dose tapering

editOne effective approach to managing caffeine dependence is dose tapering, where caffeine intake is reduced over time. This method allows the body to adjust to lower levels of caffeine gradually, minimizing withdrawal symptoms and discomfort. A study published in the Journal of Caffeine Research demonstrates the efficacy of dose tapering in reducing caffeine consumption among habitual users. Participants who followed a tapering schedule experienced fewer withdrawal symptoms and were more successful in reducing their overall caffeine intake compared to those who abruptly stopped caffeine consumption.[20]

Intermittent fasting

editIntermittent fasting, a dietary regimen that involves alternating periods of eating and fasting, has emerged as a potential strategy for managing caffeine dependence. Research suggests that intermittent fasting may help regulate caffeine intake by creating structure periods of abstaining from caffeine consumption. Additionally, intermittent fasting has been associated with improved metabolic health and cognitive function, which may support individuals in overcoming caffeine dependence.[20]

Professional counseling

editSeeking professional counseling or therapy can also be beneficial for individuals struggling with caffeine dependence. Counseling sessions provide a supportive environment for individuals to explore the underlying reasons for their caffeine consumption habits and develop coping strategies to manage cravings and withdrawal symptoms. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), in particular, has shown promise in treating substance use disorders, including caffeine dependence. A meta-analysis published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology found that CBT interventions were effective in reducing caffeine consumption and improving psychological outcomes among individuals with caffeine dependence.[citation needed]

Regular exercise

editRegular physical exercise has been shown to have numerous benefits for overall health and well-being, including aiding in the management of caffeine dependence. Engaging in regular exercise can help individuals reduce stress, improve mood, and promote better sleep quality, all of which may contribute to reducing reliance on caffeine as a stimulant.

It is important that while many adults consume caffeine on a daily basis, withdrawal symptoms may not manifest until 12–24 hours after cessation and can persist for as long as 2–9 days. Such symptoms can significantly impact daily functioning, giving rise to fatigue, headaches, irritability, nausea, mood fluctuations, flu-like symptoms, and dizziness.[31]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Bernstein, Gail A; Carroll, Marilyn E; Thuras, Paul D; Cosgrove, Kelly P; Roth, Megan E (March 2002). "Caffeine dependence in teenagers". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 66 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00181-8. PMID 11850129.

- ^ Fulgoni, Victor L; Keast, Debra R; Lieberman, Harris R (2015-05-01). "Trends in intake and sources of caffeine in the diets of US adults: 2001–2010". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 101 (5): 1081–1087. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.080077. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 25832334. S2CID 22251069.

- ^ Soltani, Sanaz; Salari-Moghaddam, Asma; Saneei, Parvane; Askari, Mohammadreza; Larijani, Bagher; Azadbakht, Leila; Esmaillzadeh, Ahmad (2021-07-05). "Maternal caffeine consumption during pregnancy and risk of low birth weight: a dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 63 (2): 224–233. doi:10.1080/10408398.2021.1945532. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 34224282. S2CID 235744429.

- ^ Juliano, Laura M.; Griffiths, Roland R. (October 2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology. 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. ISSN 0033-3158. PMID 15448977. S2CID 5572188.

- ^ Fisone, G, Borgkvist A, Usiello A (2004): Caffeine as a psychomotor stimulant: Mechanism of Action. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 61:857-872

- ^ a b Stroh, Michael. "Just one cup a day is enough to hook coffee drinkers". LA Times. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ Addicott, Merideth A. (2014). "Caffeine Use Disorder: A Review of the Evidence and Future Implications". Current Addiction Reports. 1 (3): 186–192. doi:10.1007/s40429-014-0024-9. PMC 4115451. PMID 25089257.

- ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE, Holtzman DM (2015). "Chapter 16: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-182770-6.

Addictive drugs are rewarding and reinforcing because they act in brain reward pathways to enhance either dopamine release or the effects of dopamine in the NAc or related structures, or because they produce effects similar to dopamine. ...

Long-term caffeine use can lead to mild physical dependence. A withdrawal syndrome characterized by drowsiness, irritability, and headache typically lasts no longer than a day. True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented, and, consequently, these drugs are not considered addictive. - ^ Miller PM (2013). "Chapter III: Types of Addiction". Principles of addiction comprehensive addictive behaviors and disorders (1st ed.). Elsevier Academic Press. p. 784. ISBN 9780123983619.

Astrid Nehlig and colleagues present evidence that in animals caffeine does not trigger metabolic increases or dopamine release in brain areas involved in reinforcement and reward. A single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) assessment of brain activation in humans showed that caffeine activates regions involved in the control of vigilance, anxiety, and cardiovascular regulation but did not affect areas involved in reinforcement and reward.

- ^ Sturgess JE, Ting-A-Kee RA, Podbielski D, Sellings LH, Chen JF, van der Kooy D (2010). "Adenosine A1 and A2A receptors are not upstream of caffeine's dopamine D2 receptor-dependent aversive effects and dopamine-independent rewarding effects". Eur. J. Neurosci. 32 (1): 143–54. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07247.x. PMC 2994015. PMID 20576036.

the D1 receptor is not involved in the rewarding effects of caffeine. ... The current data indicates that caffeine has aversive effects at high doses and neither rewarding nor unpleasant effects at low doses. Previous work in rats has indicated that caffeine induces mild preferences at low doses (Brockwell et al., 1991; Bedingfield et al., 1998; Patkina & Zvartau, 1998) and aversions at high doses ... Indeed the rewarding effects of caffeine seen by Brockwell et al.(1991) were at one dose and small. This is similar to our current data; the lower doses of caffeine on our dose-response curve are weakly, but non-significantly rewarding. Also consistent, the rewarding effects of caffeine in humans are mild or absent in individuals with limited caffeine experience

- ^ Volkow, N D; Wang, G-J; Logan, J; Alexoff, D; Fowler, J S; Thanos, P K; Wong, C; Casado, V; Ferre, S; Tomasi, D (April 2015). "Caffeine increases striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability in the human brain". Translational Psychiatry. 5 (4): e549–. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.46. PMC 4462609. PMID 25871974.

We show a significant increase in D2/D3R availability in striatum with caffeine administration, which indicates that caffeine at doses consumed by humans does not increase DA in striatum. Instead we interpret our findings to indicate that caffeine's DA-enhancing effects in the human brain are indirect and mediated by an increase in D2/D3R levels and/or changes in D2/D3R affinity.

- ^ Froestl, Wolfgang; Muhs, Andreas; Pfeifer, Andrea (14 November 2012). "Cognitive Enhancers (Nootropics). Part 1: Drugs Interacting with Receptors". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 32 (4): 793–887. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-121186. PMID 22886028. S2CID 10511507.

- ^ Ferré, Sergi (2016). "Mechanisms of the psychostimulant effects of caffeine: Implications for substance use disorders". Psychopharmacology. 233 (10): 1963–1979. doi:10.1007/s00213-016-4212-2. PMC 4846529. PMID 26786412.

- ^ Rodda, Simone; Booth, Natalia; McKean, Jessica; Chung, Anita; Park, Jennifer Jiyun; Ware, Paul (2020-07-01). "Mechanisms for the reduction of caffeine consumption: What, how and why". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 212: 108024. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108024. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 32442750. S2CID 218859858.

- ^ a b Studeville, George (January 15, 2010). "Caffeine Addiction Is a Mental Disorder, Doctors Say". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2005-01-22.

- ^ Hall, Harriet (5 February 2019). "Caffeine Withdrawal Headaches". Science-Based Medicine. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ Juliano, L. M.; Griffiths, R. R. (2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: Empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology. 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. PMID 15448977. S2CID 5572188.

- ^ Temple, Jennifer L.; Bernard, Christophe; Lipshultz, Steven E.; Czachor, Jason D.; Westphal, Joslyn A.; Mestre, Miriam A. (2017-05-26). "The Safety of Ingested Caffeine: A Comprehensive Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 8: 80. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00080. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 5445139. PMID 28603504.

- ^ Juliano, Laura M.; Huntley, Edward D.; Harrell, Paul T.; Westerman, Ashley T. (2012-08-01). "Development of the Caffeine Withdrawal Symptom Questionnaire: Caffeine withdrawal symptoms cluster into 7 factors". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 124 (3): 229–234. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.009. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 22341956.

- ^ a b c d e Meredith, Steven E.; Juliano, Laura M.; Hughes, John R.; Griffiths, Roland R. (September 2013). "Caffeine Use Disorder: A Comprehensive Review and Research Agenda". Journal of Caffeine Research. 3 (3): 114–130. doi:10.1089/jcr.2013.0016. ISSN 2156-5783. PMC 3777290. PMID 24761279.

- ^ "Caffeine Calculator". Roaster Coffees. 6 August 2021. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ Weibel, Janine; Lin, Yu-Shiuan; Landolt, Hans-Peter; Garbazza, Corrado; Kolodyazhniy, Vitaliy; Kistler, Joshua; Rehm, Sophia; Rentsch, Katharina; Borgwardt, Stefan; Cajochen, Christian; Reichert, Carolin Franziska (2020-04-20). "Caffeine-dependent changes of sleep-wake regulation: Evidence for adaptation after repeated intake". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 99: 109851. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109851. ISSN 0278-5846. PMID 31866308.

- ^ Branum, Amy M.; Rossen, Lauren M.; Schoendorf, Kenneth C. (March 1, 2014). "Trends in Caffeine Intake Among US Children and Adolescents". Pediatrics. 133 (3): 386–393. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2877. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 4736736. PMID 24515508.

- ^ Higgins, John P.; Babu, Kavita; Deuster, Patricia A.; Shearer, Jane (February 2018). "Energy Drinks: A Contemporary Issues Paper". Current Sports Medicine Reports. 17 (2): 65–72. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000454. ISSN 1537-890X. PMID 29420350. S2CID 46821793.

- ^ McVay, Ellen (February 19, 2020). "Is Coffee Bad For Kids?". Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (August 2010). "ACOG CommitteeOpinion No. 462: Moderate caffeine consumption during pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 467–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb2a1. PMID 20664420.

- ^ Sajadi-Ernazarova, Karima R.; Anderson, Jackie; Dhakal, Aayush; Hamilton, Richard J. (2020), "Caffeine Withdrawal", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613541, retrieved 2020-11-06

- ^ "Should I limit caffeine during pregnancy?". nhs.uk. 2018-06-27. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ^ "Caffeine Intake During Pregnancy". American Pregnancy Association. 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ^ Rodda, Simone; Booth, Natalia; McKean, Jessica; Chung, Anita; Park, Jennifer Jiyun; Ware, Paul (July 2020). "Mechanisms for the reduction of caffeine consumption: What, how and why". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 212: 108024. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108024. PMID 32442750.

- ^ Juliano, Laura M.; Huntley, Edward D.; Harrell, Paul T.; Westerman, Ashley T. (August 2012). "Development of the Caffeine Withdrawal Symptom Questionnaire: Caffeine withdrawal symptoms cluster into 7 factors". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 124 (3): 229–234. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.009. PMID 22341956.