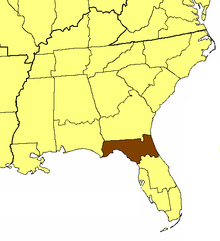

The Episcopal Diocese of Florida is a diocese of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America (ECUSA). It originally comprised the whole state of Florida, but is now bounded on the west by the Apalachicola River, on the north by the Georgia state line, on the east by the Atlantic Ocean and on the south by the northern boundaries of Volusia, Marion, and Citrus counties. Its cathedral church is St. John's Cathedral in Jacksonville.

Diocese of Florida Dioecesis Floridensis Diócesis de la Florida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Ecclesiastical province | Province IV |

| Statistics | |

| Congregations | 66 (2021) |

| Members | 23,075 (2021) |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Episcopal Church |

| Established | January 17, 1838 |

| Cathedral | St John's Cathedral |

| Language | English, Spanish |

| Current leadership | |

| Bishop | Samuel Johnson Howard Charles L. Keyser (Assistant Bishop) Dorsey F. Henderson, Jr. (Assistant Bishop) |

| Map | |

Location of the Diocese of Florida | |

| Website | |

| diocesefl.org | |

Major cities in the diocese are Jacksonville, Tallahassee and Gainesville. The diocese includes the eastern half of Franklin County, and all of the following counties: Liberty, Gadsden, Leon, Wakulla, Jefferson, Madison, Taylor, Hamilton, Suwannee, Dixie, Lafayette, Levy, Gilchrist, Columbia, Baker, Union, Bradford, Alachua, Nassau, Duval, St. Johns, Clay, Putnam and Flagler.

The diocese is a part of Province IV of the Episcopal Church. The diocese currently comprises 77 churches.[1]

History

editOn January 17, 1838, the Episcopal Church in Florida was begun in Tallahassee with seven parishes spread throughout the state:

- Christ Church, Pensacola,

- St. Joseph’s Church, St. Joseph, Florida

- Christ Church (now Trinity), Apalachicola,

- St. John’s Church, Tallahassee,

- St. John’s Church (now St. John's Cathedral), Jacksonville,

- Trinity Parish, St. Augustine

- St. Paul’s Church, Key West

The group composed a constitution and rules of order which were submitted to the General Convention, and on September 7, 1838, the Diocese of Florida was accepted into the national church body.[2] However, for all practical purposes, the Diocese existed in name only. There was not a Bishop of Florida and only a handful of clergy. Their relative geographical locations posed a huge challenge; the distance between St. Augustine and Pensacola is about 400 miles (640 km). Travel was slow and difficult, as was communication between clergy.

A few new churches were founded, but they had almost no connection to the diocese. As of 1851, there were but 260 communicants in the entire state, and many parishes were struggling to survive. That changed after the Reverend Francis Huger Rutledge was elected in October 1851 as the first Bishop of Florida.[3]

Bishop Rutledge's work transformed the diocese into an effective organization. Funds were raised, clergy was recruited and every parish was visited. Then came the Civil War. In 1861, Florida joined the Confederacy and the war devastated the South. Four Florida churches were burned down with the remainder in desperate need of repair. Some priests had abandoned their parishes and nearly everyone was destitute. Bishop Rutledge died in 1866, and the outlook was grim.

Reverend John Freeman Young (Oct. 30, 1820 – Nov. 15, 1885), translator of the Christmas hymn, "Silent Night" became the second bishop of Florida in 1867. He had earlier served as an ecumenical envoy to the Russian Orthodox Church.[4] The reconstruction was a hardship to the people, as well as the church. Growth was slow but promising. Bishop Young visited parishes throughout the state, but he saw most churches once each year. A trip from Jacksonville to Key West might take a month or more. Bishop Young reported "eleven churches built or in progress in one year"[2] in 1880. He died five years later. During his service as a bishop, he established parishes for Cubans living in Florida and for Blacks, many of whom had come to Florida from Anglican parishes in the Caribbean. At the time of his death, he was working on a Spanish translation of the Book of Common Prayer.[5]

Reverend Edwin Garner Weed was elected as the third Bishop of the Diocese of Florida in 1886. As Florida continued to grow, it became obvious that the state needed to be split into two dioceses, or at least hire a suffragan bishop, but it lacked funds. Thus, bishop Weed suggested that the southern portion be split off as a missionary jurisdiction, and funded through the national church. The General Convention approved in 1892, and so created the Missionary Jurisdiction of Southern Florida, with William Crane Gray elected its missionary bishop. Thus, the original diocese's southern boundary came to include Levy, Alachua, Putnam & St. Johns counties. After the split, the Diocese of Florida contained 43 missions and 13 parishes, but fewer than 3,000 members. Bishop Weed decided to move his seat from St. Augustine to Jacksonville because transportation was more readily available. He accomplished the move by 1895, but severe freezes in 1896 & 1897 destroyed most of North Florida's citrus industry and the Great Fire of 1901 in Jacksonville left the diocese broke. The following year, however, all parishes and missions made their Diocesan payments in full. Moreover, by 1906, the diocese had more than 50 parishes and missions, served by 33 clergy. In 1913, Bishop Weed realized that the missionary Southern diocese had grown much more rapidly than the original diocese, due to the expansion of railroad service to Tampa and Key West. He suggested returning Marion and Volusia Counties to the original diocese, but that suggestion failed when only one of the thirteen parishes in the missionary district agreed.[6] In addition, the Woman's Auxiliary gained importance and became a major source of funds during the early 1900s. Their efforts helped keep many churches from closing their doors. Bishop Weed died in 1924.

The Right Reverend Frank Alexander Juhan was the youngest American bishop when he was consecrated in 1924 at St. John's, Jacksonville. Bishop Juhan took special interest in youth and college ministries. The diocese acquired property in 1926 for use as a Summer camp and ministries were begun at Florida State College for Women (now Florida State University) and the University of Florida. In early 1929 the diocese consisted of sixteen parishes and fifty-one missions. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed did not spare Florida's churches; as was the case everywhere, salaries were cut, people were let go and missions folded. The diocese quietly celebrated its centennial in 1938. With the depression subsiding, the bishop implemented a comprehensive three-year plan of improvement and advancement. Many clergymen enlisted during World War II and ministering to the thousands of servicemen in Florida became an added burden for the remaining clergy. Bishop Juhan reported in 1943: "Believe me when I say that I can get four new tires and four hundred pounds of beef tenderloin easier than I can get able clergy now."[2] However, no church closed during the war years, and during the next decade, eleven missions became parishes and new missions were organized in sixteen communities, doubling church membership. Twenty new clergy were hired. St. Johns Church in Jacksonville became St. John's Cathedral for the Diocese of Florida. A diocesan house and bookstore were established, and a retirement home for women. In 1956, Bishop Juhan retired at age 68.

The Right Reverend Edward Hamilton West was consecrated as the Fifth Bishop of Florida on February 1, 1956, after serving as Coadjutor prior to Bishop Juhan’s retirement. Reverend West was the chaplain in charge of working with students at the University of Florida in 1936. Bishop West sought to establish more missions and improve stewardship through his Florida Plan, which was somewhat successful. After five years as bishop, there were more than 90 clergy, 15 new churches, 10 new missions and 13 new parish houses. However, when the Episcopal Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast was formed in 1971, the Diocese of Florida lost 18 clergy, 9 parishes and 13 missions in the panhandle. The late 1960s and early 1970s were turbulent years as the issues of the Vietnam War, Racial integration, and the introduction of the 1968 Book of Common Prayer led to divisiveness within individual congregations, throughout the diocese and the entire country. In spite of these problems, Episcopal High School of Jacksonville opened its doors in 1966 and a new Diocesan House was constructed in 1971. The diocese built three high-rise retirement apartment buildings in downtown Jacksonville: the Cathedral Towers in 1968, Cathedral Townhouse in 1970, and Cathedral Terrace in 1974. Bishop West retired in 1974 after having guided the diocese through a difficult period of time.

The Right Reverend Frank Stanley Cerveny was selected as the sixth bishop of the diocese in 1974. During his episcopate the church began ordaining women and made major revisions to the prayer book. Bishop Cerveny chose to focus on evangelism and spiritual growth which included a close relationship with the diocese of Cuba. Cursillo, a renewal movement for lay people led by lay people, was begun in the diocese in 1976. In 1980, Camp Weed was moved to its current location near Live Oak and became a year-round center for spiritual reflection, renewal and recreation. Bishop Cerveny retired at the end of 1993.

The Right Reverend Stephen Hays Jecko became Bishop in 1994. He began and supported ministries for the homeless, incarcerated, and the poor. Spiritual renewal programs such as Discovery and Alpha were introduced and implemented. Continuing education programs were developed to assist priests and laity. The election and consecration of Gene Robinson, an openly gay priest in the Episcopal church, was controversial, resulting in heated debate and intense feelings throughout the Episcopal Church in the United States. Bishop Jecko conducted a series of discussions and meetings for clergy, vestries and parishioners in an attempt to resolve the issue that was dividing conservative and liberal Christians. Privately, he was opposed the church’s position on the issue, and decided to leave the diocese rather than enforce the will of the national church.

Following Bishop Jecko's "retirement", the Right Reverend Samuel Johnson Howard was elected the eighth Bishop of the Diocese of Florida in 2004. Bishop Howard guided the diocese through the period of controversy resulting from the 2003 ordination of Bishop Robinson and the 2006 election of Katharine Jefferts Schori as Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States. Half a dozen parishes in the Diocese of Florida voted to withdraw from the Episcopal Church and affiliate with an Anglican coalition in North America. Bishop Howard took a hard line against those congregations and their rectors. When they refused to return to the Episcopal Church, the diocese filed suit to evict them from their church property, which was held in the name of the Diocese of Florida. Notice was given to the clergy involved that they would be defrocked. The Diocese of Florida has been a leader in the efforts to rebuild in Mississippi following 2005’s Hurricane Katrina. The diocese sent 53 mission teams comprising 300 volunteers and nearly $1 million in materials to St. Patrick's Church and its parishioners in Long Beach, Mississippi. A partnership was formed between the diocese and the organization, Prisoners of Christ which addresses the pastoral needs of incarcerated and released prisoners. Bishop Howard has announced that he will retire before the end of 2023.

Two elections have been held to choose a successor for Howard, the first in May 2022, the second in November 2022. The Reverend Charlie Holt won each election, but renounced his first election and failed to receive the required number of consents from the bishops and standing committees of other dioceses of the Episcopal Church for his second election.[7][8] Formal objections to the first election process were filed with the national church, and, in August 2022, the Court of Review of the Episcopal Church released a judgement siding with the objectors on most counts.[9] The court's finding would have been forwarded to other dioceses for their consideration as they decided whether or not to supply the required consent to the election, but Holt rescinded his acceptance of the election later in August because he desired to have a clean process.[10] The second election was also contested on procedural grounds, and again in, February 2022, the Court of Review sided with some of the objections. The diocese responded to these objections in March 2023.[11] Other dioceses had 120 days to supply their consent. Some groups also asked for consent to be withheld because of Holt's past statements or actions regarding race and LGBTQ+ individuals. Holt provided clarifications, apologized for his missteps, and stated he will not stand in the way of parishes or clergy who wish to hold same-sex weddings.[12] On July 21, 2023, the diocese and the presiding bishop announced that Holt had not received the required consents. Bishop Howard retired on October 31, 2023. Upon his retirement, the standing committee became the ecclesiastical authority for the diocese. An assisting bishop may be appointed or an election for a bishop provisional held.[13]

Camp Weed

editThe first summer camp in the Diocese was held near St. Augustine Beach in June, 1924, attended by 40 children from the Jacksonville young people’s service leagues. The following year, camp was moved to a location near Panama City on St. Andrew’s Bay. The camp was successful and was given the name Camp Weed to honor the late Right Reverend Edwin Garner Weed, Third Bishop of Florida.

The camp remained in Bay County and the Diocese purchased 10 acres (40,000 m2) of land that included four screened cottages and a former hotel in 1929. The next year, the Diocese began holding multiple camp sessions with Church school teachers and leaders conducting their own programs for 130 children. Attendance had risen to nearly 400 by the start of World War II.

The US Army commandeered Camp Weed for training during the war. The St. Joe Paper Company graciously offered property near St. Teresa, on St. James Bay, but this property was also claimed by the Army for the war effort. During the war years, the camp was temporarily moved to Hibernia, home of the historic St. Margaret's Episcopal Church and Cemetery on the St. John’s River. After the war, the camp was resumed at St. Teresa. The army buildings were transformed into dorms, a dining hall, a chapel, recreation and craft centers. The 1950s ushered in the Post-World War II baby boom and growth.

In 1971, the Episcopal Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast was formed and the Diocese of Florida lost 9 parishes and 13 missions in the panhandle. Camp Weed was no longer at the center of the diocese; it was on the western border. The Diocesan convention authorized the search for and purchase of a "centrally located site of adequate size" in 1976. Property near Live Oak was selected in 1978 and 500-acre (2.0 km2) on White Lake was purchased. The St. Teresa property was sold that same year.

The first few years were spent in tents, with primitive conditions more typical for Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts. The first permanent facilities were constructed in 1981 and the following year, 7 cabins were completed, roads were cleared, the swimming and recreation areas were built, all with the help of campers. A kitchen and dining hall were constructed in 1983. Each year, a new project was completed. Amenities now include the Cerveny Conference Center, "motel" rooms and a swimming pool. A beautiful worship facility, Mandi’s Chapel, was dedicated in 1995, and many weddings are held there. On April 18, 2012, the AIA's Florida Chapter ranked Mandi's Chapel second on its list of Florida Architecture: 100 Years. 100 Places.[14]

The Ravine building, with guest rooms and a conference room, was opened in 2004, as was the Varn Dining Hall, which seats 300. The Snell/McCarty Youth Pavilion was dedicated in 2006, providing a year-round gymnasium with a capacity of 500.

Bishops

editThe following is a list of the Bishops of the Diocese of Florida:

- 1. Francis Huger Rutledge 1851–1866 (deceased)

- 2. John Freeman Young 1867–1885 (deceased)

- 3. Edwin Gardner Weed 1886–1924 (deceased)

- 4. Frank Alexander Juhan 1924–1956 (deceased)

- 5. Edward Hamilton West 1956–1974 (deceased)

- 6. Frank Stanley Cerveny 1974–1992

- 7. Stephen Hays Jecko 1993–2004 (deceased)

- 8. Samuel Johnson Howard 2004–2023

- Charles L. Keyser, (deceased)

Parishes and missions

editThe table can be sorted by any column; left mouse click on the arrow box in the heading. P=Parish, M=Mission

| Parish Name | City | website | Region | P/M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advent | Tallahassee | [2] | Apalachee | P |

| Ascension | Carrabelle | Apalachee | P | |

| All Saints | Jacksonville | [3] Archived December 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine | 1st Coast East | P |

| All Saints Chapel | Hastings | River | M | |

| St. Gabriel's | Jacksonville | 1st Coast West | P | |

| All Soul's Chapel | Starke | Santa Fe | M | |

| Bethany | Hilliard | 1st Coast West | M | |

| Chapel of St. Dismas | Baker Correctional Institution | Santa Fe | M | |

| Christ Church | Ponte Vedra Beach | [4] | 1st Coast East | P |

| Chapel of the Incarnation | Gainesville | [5] | Santa Fe | M |

| Christ Church – San Pablo | Jacksonville | [6] | 1st Coast East | M |

| Christ Church | Monticello | [7] | Apalachee | P |

| Christ Church | Cedar Key | [8] | Santa Fe | P |

| Church of Our Saviour | Jacksonville | [9] | 1st Coast East | P |

| Church of the Holy Communion | Hawthorne | River | P | |

| Community of St. Paul | Liberty Correctional Institution | Apalachee | M | |

| Emmanuel | Welaka | River | M | |

| Epiphany | Jacksonville | [10] | 1st Coast West | P |

| Florida State Prison | Starke | Santa Fe | M | |

| Good Samaritan | Jacksonville | 1st Coast West | P | |

| Good Shepherd | Jacksonville | [11] Archived February 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine | 1st Coast West | P |

| Grace Episcopal Church | Orange Park | [12] | 1st Coast West | P |

| Grace Mission | Tallahassee | Apalachee | ||

| Holy Comforter | Crescent City | [13] | River | M |

| Holy Comforter | Tallahassee | [14] | Apalachee | P |

| Holy Trinity | Gainesville | [15] | Santa Fe | P |

| Mediator | Micanopy | Santa Fe | P | |

| Redeemer | Jacksonville | [16] | 1st Coast East | P |

| Resurrection | Jacksonville | [17] Archived May 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine | 1st Coast East | P |

| San Jose | Jacksonville | [18] | 1st Coast East | P |

| St Alban's | Chiefland | Santa Fe | P | |

| St. Andrew's | Interlachen | River | P | |

| St. Andrew's | Jacksonville | [19] Archived July 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine | 1st Coast East | P |

| St. Anne's | Keystone Heights | [20][permanent dead link] | Santa Fe | P |

| St. Barnabas | Williston | Santa Fe | M | |

| St. Bartholomew's | High Springs | [21] Archived June 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine | Santa Fe | M |

| St. Catherine's | Jacksonville | 1st Coast West | P | |

| St. Cyprian's | St. Augustine | River | M | |

| St. Elizabeth's | Jacksonville | [22] | 1st Coast West | P |

| St. Francis in the Field | Ponte Vedra Beach | [23] Archived July 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine | 1st Coast East | P |

| St. Francis of Assisi | Tallahassee | [24] | Apalachee | P |

| St. George | Jacksonville | [25] | 1st Coast East | P |

| St. James | Lake City | [26] | Santa Fe | P |

| St. James | Perry | [27] | Apalachee | P |

| St. John's Cathedral | Jacksonville | [28] | 1st Coast West | P |

| St. John's | Tallahassee | [29] | Apalachee | P |

| St. Joseph's | Newberry | [30] | Santa Fe | P |

| St. Luke's | Jacksonville | 1st Coast East | P | |

| St. Luke's | Live Oak | [31] | Santa Fe | P |

| St. Margaret's | Hibernia | [32] | 1st Coast West | P |

| St. Mark's | Jacksonville | [33] | 1st Coast West | P |

| St. Mark's | Palatka | [34] Archived July 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine | River | P |

| St. Mark's | Starke | [35] | Santa Fe | P |

| St. Mary's | Palatka | River | M | |

| St. Mary's Mission | Jacksonville | [36] | 1st Coast West | M |

| St. Mary's | Green Cove Springs | 1st Coast West | P | |

| St. Mary's | Madison | Apalachee | P | |

| St. Matthew's | Mayo | [37] | Apalachee | M |

| St. Michael and All Angels | Tallahassee | [38] | Apalachee | P |

| St. Michael's | Gainesville | Santa Fe | P | |

| St. Patrick's | Jacksonville | [39] | 1st Coast East | P |

| St John's Chapel | Jacksonville | [40] | 1st Coast East | M |

| St. Paul's by the Sea | Jacksonville Beach | [41] | 1st Coast East | P |

| St. Paul's | Federal Point | River | P | |

| St. Paul's | Jacksonville | [42] | 1st Coast East | P |

| St. Paul's | Quincy | Apalachee | P | |

| St. Peter's | Fernandina Beach | [43] | 1st Coast West | P |

| St. Peter's | Jacksonville | [44] | 1st Coast West | P |

| St. Philip's | Jacksonville | [45] | 1st Coast West | P |

| St. Teresa of Avila | Crawfordville | [46] | Apalachee | M |

| St. Teresa Prison Ministry | Wakulla Correctional Institution | Apalachee | M | |

| St. Teresa Prison Ministry | Franklin Correctional Institution | Apalachee | M | |

| St. Teresa Prison Ministry | Wakulla Work Camp | Apalachee | M | |

| St. Thomas | Palm Coast | River | P | |

| The Community of Transformation | St. John's County Detention Center | River | M | |

| Chapel of the Resurrection | Tallahassee | [47] | Apalachee | M |

| Trinity | Melrose | [48] | Santa Fe | P |

| Trinity Parish | St. Augustine | [49] | River | P |

See also

edit- St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, the original church building, now home of the Jacksonville Historical Society.

- List of Succession of Bishops for the Episcopal Church, USA

- Episcopal Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast

- Episcopal Diocese of Central Florida

- Episcopal Diocese of South Florida

- Episcopal Diocese of Southeast Florida

- Episcopal Diocese of Southwest Florida

- Episcopal Church in the United States of America

- Christianity

- Anglican Communion

References

edit- ^ The Episcopal Church Annual (2007) Harrisburg: Morehouse Church Resources, pp. 359–361.

- ^ a b c [1] Archived October 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Episcopal Diocese of Florida website, History

- ^ Cushman, Joseph D., Jr.: A Goodly Heritage: The Episcopal Church in Florida, 1821–1892, Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1965

- ^ Underwood, Byron Edward, "Bishop John Freeman Young, Translator of 'Stille Nacht,'" The Hymn, v. 8, no. 4, Oct. 1957, pp. 123–132.

- ^ Underwood, Byron Edward, op.cit.

- ^ George R. Bentley, The Episcopal Diocese of Florida, 1892-1975 (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1989), pp 76-77

- ^ Paulsen, David (July 21, 2023). "Diocese of Florida is denied churchwide consents needed to ordain Charlie Holt as bishop". Episcopal News Service. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ "Florida Bishop Election Nullified as Consent Period Ends". The Living Church. July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Paulsen, David (August 16, 2022). "Court of Review concludes Diocese of Florida bishop election was conducted improperly". Episcopal News Service. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ Paulsen, David (August 19, 2022). "Charlie Holt withdraws acceptance of election as Diocese of Florida bishop coadjutor". Episcopal News Service. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ Paulsen, David (March 22, 2023). "Diocese of Florida issues formal request for churchwide consent to disputed bishop election". Episcopal News Service. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ mmacdonald (December 20, 2022). "Florida Bishop-elect Charlie Holt commits to allowing same-sex marriage, gay ordinands if consecrated". Episcopal News Service. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ Paulsen, David (July 21, 2023). "Diocese of Florida is denied churchwide consents needed to ordain Charlie Holt as bishop". Episcopal News Service. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Florida Architecture: 100 Years. 100 Places