The 1957 Canadian federal election was held June 10, 1957, to select the 265 members of the House of Commons of Canada of the 23rd Parliament of Canada. In one of the greatest upsets in Canadian political history, the Progressive Conservative Party (also known as "PCs" or "Tories"), led by John Diefenbaker, brought an end to 22 years of Liberal rule, as the Tories were able to form a minority government despite losing the popular vote to the Liberals.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

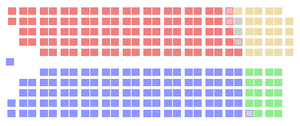

265 seats in the House of Commons 133 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 74.1%[1] ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Canadian parliament after the 1957 election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Liberal Party had governed Canada since 1935, winning five consecutive elections. Under Prime Ministers William Lyon Mackenzie King and Louis St. Laurent, the government gradually built a welfare state. During the Liberals' fifth term in office, the opposition parties depicted them as arrogant and unresponsive to Canadians' needs. Controversial events, such as the 1956 "Pipeline Debate" over the construction of the Trans-Canada Pipeline, had hurt the government. St. Laurent, nicknamed "Uncle Louis", remained popular, but exercised little supervision over his cabinet ministers.

In 1956, Tory leader George A. Drew unexpectedly resigned due to ill health. In his place, the PC party elected the fiery and charismatic Diefenbaker. The Tories ran a campaign centred on their new leader, who attracted large crowds to rallies and made a strong impression on television. The Liberals ran a lacklustre campaign, and St. Laurent made few television appearances. Uncomfortable with the medium, the Prime Minister read his speeches from a script and refused to wear makeup.

Abandoning their usual strategy of trying to make major inroads in Liberal-dominated Quebec, the Tories focused on winning seats in the other provinces. They were successful; though they gained few seats in Quebec, they won 112 seats overall to the Liberals' 105. With the remaining seats won by other parties, the PC party only had a plurality in the House of Commons, but the margin was sufficient to make John Diefenbaker Canada's first Tory Prime Minister since R. B. Bennett in 1935.

Background

editLiberal domination

editThe Tories had last governed Canada under R.B. Bennett, who had been elected in 1930.[2] Bennett's government had limited success in dealing with the Depression, and was defeated in 1935, as Liberal William Lyon Mackenzie King, who had previously served two times as prime minister, was restored to power.[3] The Liberals won five consecutive elections between 1935 and 1953, four of the victories resulting in powerful majority governments. The Liberals worked closely with the civil service (drawing several of their ministers from those ranks) and their years of dominance saw prosperity.[4]

When Mackenzie King retired in 1948, he was succeeded by Minister of Justice Louis St. Laurent, a bilingual Quebecer who took office at the age of 66.[5] An adept politician, St. Laurent projected a gentle persona and was affectionately known to many Canadians as Uncle Louis.[6] In actuality, St. Laurent was uncomfortable away from Ottawa, was subject to fits of depression (especially after 1953), and on political trips was carefully managed by advertising men from the firm of Cockfield Brown.[7] St. Laurent led the Liberals to an overwhelming triumph in the 1949 election, campaigning under the slogan "You never had it so good".[8] The Liberals won a fifth successive mandate in 1953, with St. Laurent content to exercise a highly relaxed leadership style.[9]

The Mackenzie King and St. Laurent governments laid the groundwork for the welfare state, a development initially opposed by many Tories.[10] C.D. Howe, considered one of the leading forces of the St. Laurent government, told his Tory opponents when they alleged that the Liberals would abolish tariffs if the people would let them, "Who would stop us? ... Don't take yourselves too seriously. If we wanted to get away with it, who would stop us?"[9]

Tory struggles

editAt the start of 1956, the Tories were led by former Ontario premier George A. Drew, who had been elected PC leader in 1948 over Saskatchewan MP John Diefenbaker.[11] Drew was the fifth man to lead the Tories in their 21 years out of power.[12] None had come close to defeating the Liberals; the best performance was in 1945, when John Bracken secured 67 seats for the Tories. The Liberals, though, had won 125 seats, and maintained their majority.[13] In the 1953 election, the PC party won 51 seats out of the 265 in the House of Commons.[14] Subsequently, the Tories picked up two seats from the Liberals in by-elections, and the Liberals (who had won 169 seats in 1953) lost an additional seat to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, the predecessor of the New Democratic Party (NDP)).[15]

After over two decades in opposition, the Tories were closely associated with that role in the public eye. The Tories were seen as the party of the wealthy and of English-speaking Canada and drew about 30% of the vote in federal elections. The Tories had enjoyed little success in Quebec in the past forty years.[16] By 1956, the Social Credit Party was becoming a potential rival to the Tories as Canada's main right-wing party.[17] Canadian journalist and author Bruce Hutchison discussed the state of the Tories in 1956:

When a party calling itself Conservative can think of nothing better than to outbid the Government's election promises; when it demands economy in one breath and increased spending in the next; when it proposes an immediate tax cut regardless of inflationary results ... when in short, the Conservative party no longer gives us a conservative alternative after twenty-one years ... then our political system desperately requires an opposition prepared to stand for something more than the improbable chance of quick victory.[18]

Run-up to the campaign

editIn 1955, the Tories, through a determined filibuster, were able to force the government to withdraw amendments to the Defence Procurement Act, which would have made temporary, extraordinary powers granted to the government permanent. Drew led the Tories in a second battle with the government the following year: in the so-called "Pipeline Debate", the government invoked closure repeatedly in a weeks-long debate which ended with the Speaker ignoring points of order as he had the division bells rung. Both measures were closely associated with Howe, which, in combination with his earlier comments, led to Tory claims that Howe was indifferent to the democratic process.[19]

Tory preparations for an upcoming election campaign were thrown into disarray in August 1956 when Drew fell ill. Tory leaders felt that the party needed vigorous leadership with a federal election likely to be called within a year. In September, Drew resigned.[20] Diefenbaker, who had failed in two prior bids for the leadership, announced his candidacy, as did Tory frontbenchers Davie Fulton and Donald Fleming.[21] Diefenbaker, a criminal defence lawyer from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, was on the populist left of the PC party.[22] Those Tory leaders who disliked Diefenbaker and his views, and hoped to find a candidate from Drew's conservative wing of the party, wooed University of Toronto president Sidney Smith as a candidate. However, Smith refused to run.[23]

Tory leaders scheduled a leadership convention for December. In early November, the Suez crisis erupted. Minister of External Affairs Lester Pearson played a major part in the settlement of that dispute, and was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his role. Diefenbaker, as the Tories' foreign policy critic and as the favourite in the leadership race, gained considerable attention for his speeches on Suez.[24] The Tories attacked Pearson for, as they said, being an errand boy for the United States government; he responded that it was better to be such a lackey than to be an obedient colonial doing Britain's will unquestioningly.[25] While Suez would come to be regarded by many as one of the finest moments in Canadian foreign policy, at the time it cost the Liberals support outside of Quebec.[26]

Diefenbaker was the favourite throughout the leadership campaign. At the convention in Ottawa in December, he refused to abide by the custom of having a Quebecer be either the proposer or seconder of his candidacy, and instead selected an Easterner (from New Brunswick) and a Westerner to put his name in nomination. With most Quebec delegates backing his opponents, Diefenbaker felt that having a Quebecer as a nominator would not increase his support.[27] Diefenbaker was elected on the first ballot, and a number of Quebec delegates walked out of the convention after his victory.[28] Other Diefenbaker opponents, such as those who had urged Smith to run, believed that the 61-year-old Diefenbaker would be merely a caretaker, who would serve a few years and then step down in favour of a younger man, and that the upcoming election would be lost to the Liberals regardless of who led the Tories.[29]

When Parliament convened in January, the Liberals introduced no major proposals, and proposed nothing controversial. Diefenbaker turned over his parliamentary duties to British Columbia MP Howard Green and spent much of his time on the road making speeches across the country.[30] Diefenbaker toured a nation in which Liberal support at the provincial level had slowly been eroding. When the Liberals gained Federal power in 1935, they controlled eight of the nine provincial governments, all except Alberta. By early 1957, the Liberals controlled the legislatures only in the tenth province, Newfoundland, and in Prince Edward Island and Manitoba.[30]

In March, Finance Minister Walter Harris, who was believed to be St. Laurent's heir apparent,[31] introduced his budget. The budget anticipated a surplus of $258 million, of which $100 million was to be returned in the form of increased welfare payments, with an increase of $6 per month (to a total of $46) for old age pensioners—effective after the election. Harris indicated that no more could be returned for fear of increasing inflation.[32] Diefenbaker attacked the budget, calling for higher old age pensions and welfare payments, more aid to the poorer provinces, and aid to farmers.[33]

St. Laurent had informed Diefenbaker that Parliament would be dissolved in April, for an election on June 10. A final parliamentary conflict was sparked by the suicide of Canadian Ambassador to Egypt E.H. Norman in the midst of allegations made by a United States Senate subcommittee that Norman had communist links. Pearson had defended Norman when the allegations became public, and defended him again after his death, suggesting to the Commons that the allegations were false. It quickly became apparent that the information released by the Americans might have come from Canadian intelligence sources, and after severe questioning of Pearson by Diefenbaker and the other parties' foreign policy critics, Pearson made a statement announcing that Norman had had communist associations in his youth, but had passed a security review. The minister evaded further questions regarding what information had been provided, and the discussion was cut short when Parliament was dissolved on April 12.[34]

Peter Regenstreif, who studied the four elections between 1957 and 1963, wrote of the situation at the start of the election campaign, "In 1957, there was no tangible indication that the Liberals would be beaten or, even in the opposition's darkest moment of reflection, could be. All the hindsight and post hoc gazing at entrails cannot change that objective fact."[35]

Issues

editThe Liberals and PC party differed considerably on fiscal and tax policies. In his opening campaign speech at Massey Hall in Toronto, Diefenbaker contended that Canadians were overtaxed in the amount of $120 per family of four.[36] Diefenbaker pledged to reduce taxes and castigated the Liberals for not reducing taxes despite the government surplus.[36] St. Laurent also addressed tax policy in his opening speech, in Winnipeg. St. Laurent noted that since 1953, tax rates had declined, as had the national debt, and that Canada had a reputation as a good place for investments. The Prime Minister argued that the cost of campaign promises made by the Progressive Conservatives would inevitably drive up the tax rate.[37] Diefenbaker also assailed tight-money monetary policies which kept interest rates high, complaining that they were hitting Atlantic and Western Canada hard.[38]

The Tories promised changes in agricultural policies. Many Canadian farmers were unable to find buyers for their wheat; the PC party promised generous cash advances on unsold wheat and promised a protectionist policy regarding foreign agricultural products. The Liberals argued that such tariffs were not worth the loss of bargaining position in efforts to seek foreign markets for Canadian agricultural products.[39]

The institution of the welfare state was by 1957 accepted by both major parties. Diefenbaker promised to expand the national health insurance scheme to cover tubercular and mental health patients.[40] He characterized the old age pension increase which the Liberal government was instituting as a mere pittance, not even enough to keep up with the cost of living. Diefenbaker noted that the increase only amounted to twenty cents a day,[38] using that figure to ridicule Liberal contentions that an increase would add to the rate of inflation. All three opposition parties promised to increase the pension, with the Social Crediters and CCF even stating the specific amounts it would be raised by.[40]

The Liberals were content to rest on their record in foreign affairs, and doubted that the Tories could better them. In a radio address on May 30, Minister of Transport George Marler commented, "You will wonder as I do who in the Conservative Party would take the place of the Honourable Lester Pearson, whose knowledge and experience of world affairs has been put to such good use in recent years."[41] Diefenbaker, however, refused to concede the point and in a televised address stated that Canadians were "asking Pearson to explain his bumbling of External Affairs".[42] Though they were reluctant to discuss the Norman affair, the Tories suggested that the government had irresponsibly allowed gossip to be transmitted to United States congressional committees. They also attacked the government over Pearson's role in the Suez settlement, suggesting that Canada had let Britain down.[43]

Some members of the Tories' campaign committee had urged Diefenbaker not to build his campaign around the Pipeline Debate, contending that the episode was now a year in the past and forgotten by the voters, who did not particularly care what went on in Parliament anyway. Diefenbaker replied, "That's the issue, and I'm making it."[44] Diefenbaker referred to the conduct of the government in the Pipeline Debate more frequently than he did any other issue during the campaign.[45] St. Laurent initially dealt with the question flippantly, suggesting in his opening campaign address that the debate had been "nearly as long as the pipeline itself and quite as full of another kind of natural gas".[46] As the issue gained resonance with the voters, the Liberals devoted more time to it, and St. Laurent devoted a major part of his final English television address to the question.[46] The Liberals defended their conduct, and contended that a minority should not be allowed to impose its will on an elected majority. St. Laurent suggested that the Tories had performed badly as an opposition in the debate, and suggested that the public give them more practice at being an opposition.[47]

Finally, the Tories contended that the Liberals had been in power too long, and that it was time for a change. The PC party stated that the Liberals were arrogant, inflexible, and not capable of looking at problems from a new point of view.[48] Liberals responded that with the country prosperous, there was no point to a change.[49]

Campaign

edit| Polling firm | Date | Lib | PC | Undecided/no answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C.I.P.O. | October 1956 | 49.0 | 32.7 | 15.1 |

| C.I.P.O | January 1957 | 50.6 | 31.7 | 19.8 |

| C.I.P.O. | March 1957 | 46.0 | 32.9 | 26.2 |

| C.I.P.O. | May 4–10, 1957 | 46.8 | 32.9 | 14.7 |

| C.I.P.O. | May 28–June 1, 1957 | 43.3 | 37.5 | 12.8 |

| C.I.P.O. (forecast) | June 8, 1957 | 48.0 | 34.0 | – |

| Results | June 10, 1957 | 40.5 | 38.5 | – |

Progressive Conservative

editIn 1953, almost half of the Tories' campaign funds were spent in Quebec, a province in which the party won only four of seventy-five seats. After the 1953 election, Tory MP Gordon Churchill studied the Canadian federal elections since Confederation. He concluded that the Progressive Conservatives were ill-advised to continue pouring money into Quebec in an effort to win seats in the province; the Tories could win at least a minority government by maximizing their opportunities in English-speaking Canada, and if the party could also manage to win twenty seats in Quebec, it could attain a majority. Churchill's conclusions were ignored by most leading Tories—except Diefenbaker.[51]

Diefenbaker's successful leadership race had been run by Allister Grosart, an executive for McKim Advertising Ltd. Soon after taking the leadership, Diefenbaker got Grosart to help out at Tory headquarters, and soon appointed him national director of the party and national campaign manager.[52] Grosart appointed a national campaign committee, something which had not been done previously by the Tories, but which, according to Grosart, provided the organizational key to success in 1957.[53] The party was ill-financed, having only $1,000,000 to wage the campaign—half what it had in 1953. Grosart divided most of that money equally by constituency, to the disgruntlement of Quebec Tories, who were used to receiving a disproportionate share of the national party's financing.[54]

The Tory campaign opened at Massey Hall in Toronto on April 25, where Diefenbaker addressed a crowd of 2,600, about 200 short of capacity. At the Massey Hall rally, a large banner hung behind Diefenbaker, which did not mention the name of his party, but which instead stated, "It's Time for a Diefenbaker Government."[55] The slogan, coined by Grosart, sought to blur Canadian memories of the old Tory party of Bennett and Drew and instead focus attention on the party's new leader.[55] Posters for election rallies contained Diefenbaker's name in large type; only the small print contained the name of the party. When St. Laurent complained that the Tories were not campaigning under their own name, Grosart sent copies of the Prime Minister's remarks in a plain envelope to every Liberal candidate, and was gratified when they began inserting the allegation into their own speeches. According to Professor J. Murray Beck in his history of Canadian general elections, "His political enemies were led to make the very point he was striving to drive home: Diefenbaker was, in effect, leading a new party, not an old one with a repellent image."[56] Grosart later stated that he structured the entire campaign around the personality of John Diefenbaker, and threw away the Tory party and its policies.[57]

Diefenbaker began his campaign with a week of local campaigning in his riding, after which he went to Toronto for the Massey Hall speech.[58] After two days in Ontario, he spoke at a rally in Quebec City, before spending the remainder of the first week in the Maritimes. The next week saw Diefenbaker spend two days in Quebec, after which he campaigned in Ontario. The next two weeks included a Western tour, with brief returns to Ontario, the most populous province. The final two weeks saw Diefenbaker spend much of the time in Ontario, though with brief journeys east to the Maritimes and Quebec and twice west to Saskatchewan. He returned to his riding for the final weekend before the Monday election.[59] He spent 39 days on the campaign trail, eleven more than the Prime Minister.[60]

According to Professor John Meisel, who wrote a book about the 1957 campaign, Diefenbaker's speaking style was "reminiscent of the fiery orators so popular in the nineteenth century. Indeed, Mr. Diefenbaker's oratory has been likened to that of the revivalist preacher."[61] As a new face on the national scene given to outspoken attacks on the government, he began to attract unexpectedly large crowds early in the campaign.[61] When reduced to the written word, however, Diefenbaker's rhetoric sometimes proved to be without much meaning. According to journalist and author Peter C. Newman, "On the printed page, it makes little sense. But from the platform, its effect was far different."[62] Both Newman and Meisel cite as an example of this the conclusion to the leader's Massey Hall speech:

If we are dedicated to this—and to this we are—you, my fellow Canadians, will require all the wisdom, all the power that comes from those spiritual springs that make freedom possible—all the wisdom, all the faith and all the vision which the Conservative Party gave but yesterday under Macdonald, change to meet changing conditions, today having the responsibility of this party to lay the foundations of this nation for a great and glorious future.[62][63]

Diefenbaker's speeches contained words which evoked powerful emotions in his listeners. His theme was that Canada was on the edge of greatness—if it could only get rid of its incompetent and arrogant government. He stressed that the only alternative to the Liberals was a "Diefenbaker government".[64] According to Newman, Diefenbaker successfully drew on the discontent both of those who had prospered in the 1950s, and sought some deeper personal and national purpose, as well as those who had been left out of the prosperity.[65] However, Diefenbaker spoke French badly and the excitement generated by his campaign had little effect in francophone Quebec, where apathy prevailed and Le Devoir spoke of "une campaigne électorale au chloroforme".[a][66]

The Tories had performed badly in British Columbia in 1953, finishing a weak fourth.[67] However, the province responded to Diefenbaker, and 3,800 turned out for his Victoria speech on May 21, his largest crowd yet. This was bettered two days later in Vancouver with a crowd of 6,000, with even the street outside the Georgia Street Auditorium packed with Tory partisans. Diefenbaker responded to this by delivering what Dick Spencer (who wrote a book on Diefenbaker's campaigns) considered his greatest speech of the 1957 race,[68] and which Newman considered the turning point of Diefenbaker's campaign.[60] Diefenbaker stated, "I give this assurance to Canadians—that the government shall be the servant and not the master of the people ... The road of the Liberal party, unless it is stopped—and Howe has said, 'Who's going to stop us?'—will lead to the virtual extinction of parliamentary government. You will have the form, but the substance will be gone."[69]

The Liberal-leaning Winnipeg Free Press, writing shortly after Diefenbaker's speeches in British Columbia, commented on them:

Facts were overwhelmed with sound, passion substituted for arithmetic, moral indignation pumped up to the bursting point. But Mr. Diefenbaker provided the liveliest show of the election ... and many listeners undoubtedly failed to notice that he was saying even less than the Prime Minister, though saying it more shrilly and with evangelistic fervour ... Mr. Diefenbaker has chosen instead to cast himself as the humble man in a mood of protest, the common Canadian outraged by Liberal prosperity, the little guy fighting for his rights.

So far as the crowds mean anything, that posture is a brilliant success at one-night stands.[70]

On June 6, the two major party campaigns crossed paths in Woodstock, Ontario. Speaking in the afternoon, St. Laurent drew a crowd of 200. To the shock of St. Laurent staffers, who remained for the Diefenbaker appearance, the PC leader drew an overflow crowd of over a thousand that evening, even though he was an hour late, with announcements made to the excited crowd that he was slowed by voters who wanted only to see him or shake his hand.[71]

Diefenbaker's intensive campaign exhausted the handful of national reporters who followed him. Clark Davey of The Globe and Mail stated, "We did not know how he did it."[72] Reporters thought the Progressive Conservatives might, at best, gain 30 or 35 seats over the 53 they had at dissolution, and when Diefenbaker, off the record, told the reporters that the Tories would win 97 seats (which would still allow the Liberals to form the government), they concluded he was guilty of wishful thinking.[72] Diefenbaker was even more confident in public; after he concluded his national tour and returned to his constituency, he addressed his final rally in Nipawin, Saskatchewan: "On Monday, I'll be Prime Minister."[73]

Liberal

editSt. Laurent was utterly confident of an election victory,[74] so much so that he did not even bother to fill the sixteen vacancies in the Senate.[60] He had been confident of re-election when Drew led the Tories, and, according to Liberal minister Lionel Chevrier, Diefenbaker's victory in the party leadership race increased his confidence by a factor of ten.[74] At his press conference detailing his election tour, St. Laurent stated, "I have no doubt about the election outcome."[75] He indicated that his campaign would open April 29 in Winnipeg, and that the Prime Minister would spend ten days in Western Canada before moving east.[75] However, he indicated he would first go home to Quebec City for several days around Easter (April 21 in 1957). This break kept him out of the limelight for ten days at a time when Diefenbaker was already actively campaigning and making daily headlines.[76] At a campaign stop in Jarvis, Ontario, St. Laurent told an aide that he was afraid the right-wing, anti-Catholic Social Credit Party would be the next Opposition.[77] St. Laurent denied Opposition claims that he would resign after an election victory, and the 75-year-old indicated that he planned to run again in 1961, if he was still around.[78]

The Liberals made no new, radical proposals during their campaign, but instead ran a quiet campaign with occasional attacks on the opposition parties. They were convinced that the public still supported their party, and that no expensive promises need be made to voters.[79] St. Laurent was made the image of the nation's prosperity, and the Liberals refused to admit any reason for discontent existed.[80] When Minister of Finance Harris proposed raising the upcoming increase in old age pension by an additional four dollars a month, St. Laurent refused to consider it, feeling that the increase had been calculated on the basis of the available facts, and those facts had not changed.[81]

During the Prime Minister's Western swing, St. Laurent made formal speeches only in major cities. In contrast to Diefenbaker's whistle-stop train touring, with a hasty speech in each town as the train passed through, the Liberals allowed ample time for "Uncle Louis" to shake hands with voters, pat their children on the head, and kiss their babies.[78] In British Columbia, St. Laurent took the position that there were hardly any national issues worth discussing—the Liberals had brought Canada prosperity and all that was needed for more of the same was to return the party to office.[82] After touring Western Canada, St. Laurent spent the remainder of the second week of the campaign returning to, and in, Ottawa. The third week opened with a major speech in Quebec City, followed by intensive campaigning in Ontario. The fifth week was devoted to the Maritime provinces and Eastern Quebec. The sixth week opened with a major rally in Ottawa, before St. Laurent returned to the Maritimes and Quebec, and the final week was spent in Ontario before St. Laurent returned to his hometown of Quebec City for the election.[59]

St. Laurent tried to project an image as a family man, and to that end often addressed schoolchildren. As he had in previous elections, he spoke to small groups of children regarding Canadian history or civics.[83] The strategy backfired while addressing children in Port Hope, Ontario. With the children inattentive, some playing tag or sticking cameras in his face, St. Laurent angrily told them that it was their loss if they did not pay attention, as the country would be theirs to worry about far longer than it would be his.[84]

St. Laurent and the Liberals suffered other problems during the campaign. According to Newman, St. Laurent sometimes seemed unaware of what was happening around him, and at one campaign stop, shook hands with the reporters who were following him, under the apparent impression they were local voters.[77] On the evening of Diefenbaker's Vancouver speech, St. Laurent drew 400 voters to a rally in Sherbrooke, Quebec, where he had once lived.[81] C.D. Howe, under heavy pressure from the campaign of CCF candidate Doug Fisher in his Ontario riding, intimated that Fisher had communist links.[85] At a rally in Manitoba,[85] Howe offended a voter who told him the farmers were starving to death, poking the voter in the stomach and saying "Looks like you've been eating pretty well under a Liberal government."[81] At another rally, Howe dismissed a persistent Liberal questioner, saying "Look here, my good man, when the election comes, why don't you just go away and vote for the party you support? In fact, why don't you just go away?"[85]

The Liberals concluded their campaign with a large rally at Toronto's Maple Leaf Gardens on June 7. Entertainment at the event was provided by the Leslie Bell singers, and according to Grosart, many in the audience were Tory supporters who had turned out to hear them.[86] St. Laurent's speech at the rally was interrupted when William Hatton, a 15-year-old boy from Malton, Ontario, climbed onto the platform. Hatton carried a banner reading, "This Can't Be Canada" with a Liberal placard bearing St. Laurent's photograph, and moved to face the Prime Minister.[87] Meisel describes Hatton as an "otherwise politically apathetic boy who ... slowly and deliberately tore up a photograph of the Prime Minister as the latter was speaking" and states that Hatton engaged in "intensely provocative behavior".[88] Liberal partisans interceded, and in the ensuing fracas, Hatton fell from the platform, audibly hitting his head on the concrete floor.[84] St. Laurent watched in apparent shock, according to his biographer Dale Tompson, as officials aided the boy and took him from the hall. According to Tompson, the crowd "turned its indignation on the men on the platform" and spent the remainder of the evening wondering about the boy's possible injuries rather than listening to the Prime Minister's speech.[89] Hatton was not seriously injured, but, according to Newman, "the accident added to the image of the Liberal Party as an unrepentant arrogant group of old men, willing to ride roughshod over voters".[85] Grosart later described the incident as "the turning point" of the campaign.[90] Professor Meisel speculated that the Hatton incident might have been part of an organized campaign to annoy St. Laurent out of his pleasant "Uncle Louis" persona,[88] and Grosart later related that Liberal frontbencher Jack Pickersgill always accused him of being behind the boy's actions, but that the incident was "a sheer accident".[86] Hatton's mother described his actions as "[j]ust a schoolboy prank," and a reaction to reading an article about how the art of heckling was dying.[91] According to public relations executive J.G. Johnston in a letter to Diefenbaker on June 10, Hatton had come to the rally with several other boys, including Johnston's son, but had gone off on his own while the other boys paraded with Diefenbaker posters which had been smuggled inside. According to Johnston, Hatton was caught on CBC tape saying to St. Laurent, "I can no longer stand your hypocrisy, Sir" before tearing the St. Laurent poster. Attempts by Johnston to have the Liberal activist who pushed Hatton off the platform arrested failed, according to Johnston, on the ground that the police could find no witnesses.[92]

CCF

editThe CCF was a socialist party, which had much of its strength in Saskatchewan, though it ran candidates in several other provinces. At Parliament's dissolution in April 1957, it had 23 MPs, from five different provinces. Aside from the Liberals and the Tories, it was the only party to nominate a candidate in a majority of the ridings.[93] In 1957, the party was led by Saskatchewan MP M.J. Coldwell.[94]

In 1956, the party adopted the Winnipeg Declaration, a far more moderate proposal than its previous governing document, the 1933 Regina Manifesto. For example, the Regina Manifesto pledged the CCF to the eradication of capitalism; the Winnipeg Declaration recognized the utility of private ownership of business, and stated that the government should own business only when it was in the public interest.[95] In its election campaign, the CCF did not promise to nationalize any industries. It promised changes in the tax code in order to increase the redistribution of wealth in Canada. It pledged to increase exemptions from income tax, to allow medical expenses to be considered deductions from income for tax purposes, and to eliminate sales tax on food, clothing, and other necessities of life. It also promised to raise taxes on the higher income brackets and to eliminate the favourable tax treatment of corporate dividends.[96]

The CCF represented many agricultural areas in the Commons, and it proposed several measures to assure financial security for farmers. It proposed national growers' cooperatives for agricultural products which were exported. It proposed cash advances for farm-stored wheat, short and long-term loans for farmers at low interest rates, and government support of prices, to assure the farmer a full income even in bad years. For the Atlantic fisherman, the CCF proposed cash advances at the start of the fishing season and government-owned depots which would sell fishing equipment and supplies to fishermen at much lower than market prices.[97]

Coldwell suffered from a heart condition, and undertook a much less ambitious schedule than the major party leaders. The party leader left Ottawa for his riding, Rosetown—Biggar in Saskatchewan, on April 26, and remained there until May 10. He spent three days campaigning in Ontario, then moved west to the major cities of the prairie provinces and British Columbia, before returning to his riding for the final days before the June 10 election. Other CCF leaders took charge of campaigning in Quebec and the Maritimes.[98]

Social Credit

editBy 1957, the Social Credit Party of Canada had moved far afield from the theories of social credit economics, which its candidates rarely mentioned.[99] Canada's far-right party, the Socreds were led by Solon Low, though its Alberta leader, Premier Ernest Manning, was highly influential in the party.[99] The Socreds' election programme was based on the demand "that Government get out of business and make way for private enterprise" and on their hatred of "all government-inspired schemes to degrade man and make him subservient to the state or any monopoly".[99]

The Socreds proposed an increase in the old age pension to $100 per month. They called for the reversal of the government's tight money policies, and for low income loans for small business and farmers. It asked for income tax exemptions to be increased to meet the cost of living, and a national housing programme to make home ownership possible for every Canadian family. The party called for a national security policy based on the need for defence, rather than "aggression", and for a foreign policy which would include food aid to the less-developed nations.[100]

The Socreds also objected to the CBC and other spending in the arts and broadcasting. The party felt that the government should solve economic problems before spending money on the arts.[101]

Low challenged the Prime Minister over the Suez issue, accusing him of sending a threatening telegram that caused British Prime Minister Anthony Eden to back off the invasion and so gave the Soviets the opportunity for a military buildup in Egypt. St. Laurent angrily denied the charge and offered to open his correspondence to any of the fifty privy councillors who could then announce whether St. Laurent was telling the truth.[102] Low took St. Laurent up on his challenge, and selected the only living former prime minister, Tory Arthur Meighen, but the matter was not resolved before the election, and Meighen was not called upon to examine the correspondence in the election's aftermath.[103]

The Social Credit Party was weakened by considerable conflict between its organizations in the two provinces it controlled, Alberta and British Columbia. It failed to establish a strong national office to run the campaign due to infighting between the two groups. However, it was better financed than the CCF, due to its popularity among business groups in the West.[104]

The Socreds hoped to establish themselves in Ontario, and scheduled their opening rally for Massey Hall in Toronto. The rally was a failure, and even though it ran 40 candidates in Ontario (up from 9 in 1953), the party won no seats in the province.[105]

Use of television

editIn 1957, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation gave the four recognized parties free air time for political statements. The television broadcast's audio tracks served also for use on radio.[106] The three opposition parties gave their party leader all of the broadcast time,[107] though Diefenbaker, who did not speak French well,[108] played only a limited role in the Tories' French-language broadcasts. In one, he introduced party president Léon Balcer, a Quebecer, who gave the speech.[106] Diefenbaker had no objection to makeup and, according to Meisel, was prepared to adopt any technique which would make his presentation more effective.[106] A survey in populous southwestern Ontario showed that Diefenbaker made the strongest impression of the four leaders.[107]

According to Liberal minister Paul Martin Sr. (the father of the future Prime Minister), St. Laurent had the potential to be quite good on television, but disliked the medium.[107] He was prejudiced against television appearances, considering such speeches the equivalent of carefully planned performances, such as stage shows.[105] He refused to be made up for the telecasts, and insisted on reading his speech from a script. His advisers switched him to a teleprompter, but this failed to make his performances more relaxed.[106] When reading, he would rarely look at the camera.[105] However, St. Laurent made only occasional television appearances (three in each language),[106] letting his ministers make the remainder.[107] Only one cabinet member, Minister of National Defence Ralph Campney took advantage of the course in television techniques offered by the Liberal Party in a dummy studio in its Ottawa headquarters.[77] This lack of preparation, according to Meisel, led to "a fiasco" during a television address by Minister of Justice Stuart Garson in early June when the teleprompter stopped working during the speech and Garson "was unable to cope effectively with the failure".[109]

Election

editMost predictions had the Tories picking up seats, but the Liberals maintaining a majority. The New York Times reported that Liberals expected to lose a majority of Ontario's seats, but retain a narrow majority in the House of Commons.[110] Time magazine predicted a Tory gain of 20 to 40 seats and stated that any result which denied the Liberals 133 seats and a majority "would rank as a major upset".[111] Beck indicates that many journalists, including those sympathetic to the Tories, saw signs of the coming upset, but disregarded them, convinced that the government was invulnerable.[112] Maclean's, which printed its postelection issue before the election to go on sale the morning after, ran an editorial noting that Canadians had freely chosen to reelect the Liberal Party.[113]

On Election Night, the first returns came in from Sable Island, Nova Scotia. Usually a Liberal stronghold, the handful of residents there favoured the Tories by two votes.[114] St. Laurent listened to the election returns on a radio in the living room of his home on Grande Allée in Quebec City, and when the radio broke, moved to an upstairs television set.[114] Diefenbaker began the evening at his house in Prince Albert, and once his re-election to the Commons was certain, moved to his local campaign headquarters.[115]

The Conservatives did well in Atlantic Canada, gaining two seats in Newfoundland and nine in Nova Scotia, and sweeping Prince Edward Island's four seats. However, in Quebec, they gained only five seats as the province returned 62 Liberals. The Tories gained 29 seats in Ontario. Howe was defeated by Fisher, and told the media that some strange disease was sweeping the country, but as for him, he was going to bed.[116] The Liberals still led by a narrow margin as the returns began to come in from Manitoba, and St. Laurent told Liberal minister Pickersgill that he hoped that the Tories would get at least one more seat than the Liberals so they could get out of an appalling situation.[31] As the Tories forged ahead in Western Canada, Diefenbaker flew from Prince Albert to Regina to deliver a television address and shouted to Grosart as yet another cabinet minister was defeated, "Allister, how does the architect feel?"[31] Late that evening, St. Laurent went to the Château Frontenac hotel for a televised speech, delivered before fifty supporters.[116]

The Tories finished with 112 seats to the Liberals' 105, while both the CCF and Social Credit gained seats in Western Canada and finished with 25 and 19 seats respectively. Nine cabinet ministers, including Howe, Marler, Garson, Campney and Harris were defeated.[117] Though the Liberals outpolled the Tories by over 100,000 votes, most of those votes were wasted running up huge margins in Quebec.[118] St. Laurent could have constitutionally hung onto power until defeated in the House, but he chose not to, and John Diefenbaker took office as Prime Minister of Canada on June 21, 1957.[118]

Irregularities

editAfter the election, the Chief Electoral Officer reported to the Speaker of the House of Commons that "the general election appears to have been satisfactorily conducted in accordance with the procedure in the Canada Elections Act".[119]

There were, however, a number of irregularities. In the Toronto riding of St. Paul's, four Liberal workers were convicted of various offences for adding almost five hundred names to the electoral register. One of the four was also convicted for two counts of perjury. While the unsuccessful Liberal candidate, former MP James Rooney, was not charged, Ontario Chief Justice James Chalmers McRuer, who investigated the matter, doubted that this could have been done without the candidate's knowledge.[120]

Various violations of law, including illicitly opening ballot boxes, illegal possession of ballots, and adding names to the electoral register, took place in twelve Quebec ridings. The RCMP felt it had enough evidence to prosecute in five ridings, and a total of twelve people were convicted. The offences did not affect the outcome of any races.[121]

The election of the Liberal candidate in Yukon was contested by the losing Tory candidate. After a trial before the Yukon Territorial Court, that court voided the election, holding that enough ineligible people had been permitted to vote to affect the outcome, though the court noted that it was not the fault of the Liberal candidate that these irregularities had occurred. The Tory, Erik Nielsen, won the new election in December 1957.[121][122]

The election in one Ontario riding, Wellington South was postponed pursuant to statute after the death of the Liberal candidate and MP, Henry Alfred Hosking during the campaign. The Tory candidate, Alfred Hales, defeated Liberal David Tolton and CCF candidate Thomas Withers on July 15, 1957.[123]

Impact

editThe unexpected defeat of the Liberals was ascribed to various causes. The Ottawa Citizen stated that the defeat could be attributed to "the uneasy talk ... that the Liberals have been in too long."[124] Tom Kent of the Winnipeg Free Press, a future Liberal deputy minister, wrote that though the Liberal record had been the best in the democratic world, the party had failed miserably to explain it.[124] Author and political scientist H.S. Ferns disagreed with Kent, stating that Kent's view reflected the Liberal "assumption that 'Nobody's going to shoot Santa Claus'" and that Canadians in the 1957 election were motivated by things other than material interests.[124] Peter Regenstreif cited the Progressive Conservative strategy in the 1957 and 1958 elections "as classics of ingenuity unequalled in Canadian political history. Much of the credit belongs to Diefenbaker himself; at least some must go to Allister Grosart".[125] A survey taken of those who abandoned the Liberals in 1957 showed that 5.1% did so because of Suez, 38.2% because of the Pipeline Debate, 26.7% because of what they considered an inadequate increase in the old age pension, and 30% because it was time for a change.[126]

The results of the election surprised the civil service as much as it did the rest of the public. Civil servant and future Liberal minister Mitchell Sharp asked C.D. Howe's replacement as Minister of Trade and Commerce, Gordon Churchill, not to come to the Ministry's offices for several days as they were redecorating. Churchill later learned that the staff were moving files out.[127] When Churchill finally came to the Ministry's offices, he was met with what he termed "the coldest reception that I have ever received in my life".[127] The new Minister of Labour, Michael Starr, was ticketed three days in a row for parking in the minister's spot.[127]

St. Laurent resigned as leader of the Liberal Party on September 5, 1957, but agreed to stay on until a successor was elected. With a lame-duck leader, the Liberals were ineffective in opposition.[128] Paul Martin stated that "I'm sure I never thought the day would come when [Diefenbaker] would ever be a member of a government, let alone head of it. When that happened, the world had come to an end as far as I was concerned."[129] In January 1958, St. Laurent was succeeded by Lester Pearson.[130]

Even in reporting the election result, newspapers suggested that Diefenbaker would soon call another election and seek a majority.[131] Quebec Tory MP William Hamilton (who would soon become Postmaster General under Diefenbaker) predicted on the evening of June 10 that there would soon be another election, in which the Tories would do much better in Quebec.[132] The Tory government initially proved popular among the Canadian people,[133] and shortly after Pearson became Liberal leader, Diefenbaker called a snap election.[134] On March 31, 1958, the Tories won the greatest landslide in Canadian federal electoral history in terms of the percentage of seats, taking 208 seats (including fifty in Quebec) to the Liberals' 48, with the CCF winning eight and none for Social Credit.[135]

Michael Bliss, who wrote a survey of the Canadian Prime Ministers, alluded to Howe's dismissive comments regarding the Tories as he summed up the 1957 election:

The pipeline debate of 1956 sparked a dramatic opposition stand on the importance of free parliamentary debate. Their arrogance did the Grits [Liberals] enormous damage, contributing heavily to the government's problems in the 1957 general election. Under the glare of television cameras in that campaign, St. Laurent, Howe, and company now appeared to be a lot of wooden, tired old men who had lost touch with Canada. The voters decided to stop them.[136]

National results

editTurnout: 74.1% of eligible voters voted.[137]

| Party | Party leader | # of candidates |

Seats | Popular vote[137] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Elected | % Change | # | % | pp Change | ||||

| Progressive Conservative | John Diefenbaker | 256 | 51 | 112 | +119.6% | 2,572,926 | 38.5% | +7.8 | |

| Liberal | Louis St. Laurent | 264 | 169 | 105 | -38.% | 2,702,573 | 40.45% | -7.8 | |

| Co-operative Commonwealth | M.J. Coldwell | 162 | 23 | 25 | +8.7% | 707,659 | 10.59% | -0.6 | |

| Social Credit | Solon Low | 114 | 15 | 19 | +26.7% | 437,049 | 6.54% | +1.1 | |

| Other | 66 | 7 | 4 | - | 188,510 | 2.8% | -0.6 | ||

| Rejected ballots | - | - | - | - | 74,710 | 1.1% | 0 | ||

| Total | 862 | 265 | 265 | - | 6,680,690 | 100.00% | |||

- The Other 4 seats were (2) Independent, (1) Independent Liberal, (1) Independent PC. One Liberal-Labour candidate was elected and sat with the Liberal caucus, as happened after the 1953 election.

Vote and seat summaries

editResults by province

edit| Party Name | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL | NW | YK | Total[137] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progressive Conservative | Seats: | 7 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 61 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 2 | - | - | 112 | |

| Vote (%): | 32.5 | 27.4 | 23.0 | 35.5 | 48.1 | 30.7 | 48.1 | 50.1 | 52.0 | 37.4 | 31.0 | 48.2 | 38.5 | ||

| Liberal | Seats: | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 21 | 62 | 5 | 2 | - | 5 | 1 | 1 | 105 | |

| Vote (%): | 20.4 | 27.6 | 30.2 | 25.8 | 36.6 | 56.8 | 47.5 | 45.9 | 46.4 | 61.3 | 66.4 | 49.5 | 40.5 | ||

| Co-operative Commonwealth | Seats: | 7 | - | 10 | 5 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 25 | |||

| Vote (%): | 22.6 | 6.3 | 35.8 | 23.4 | 11.9 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 10.6 | ||||

| Social Credit | Seats: | 6 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 19 | |||||

| Vote (%): | 23.6 | 37.5 | 10.4 | 13.0 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 6.5 | ||||||

| Other | Seats: | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Vote (%): | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 5.5 | 1.3 | 2.8 | |||||||

| Total Seats | 22 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 85 | 75 | 10 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 265 | ||

See also

editNotes and references

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ an election campaign of chloroform

References

edit- ^ "Voter Turnout at Federal Elections and Referendums". Elections Canada. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Bliss 2004, pp. 111.

- ^ Bliss 2004, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Bliss 2004, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Bliss 2004, p. 177.

- ^ Bliss 2004, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Bliss 2004, pp. 180–182.

- ^ Bliss 2004, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b Bliss 2004, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Bliss 2004, pp. 179, 183.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Bliss 2004, pp. 118, 170, 188.

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 256.

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 286.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 12.

- ^ Regenstreif 1965, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 16.

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 291.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 203.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, p. 13.

- ^ Bliss 2004, p. 194.

- ^ Bliss 2004, p. 187.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Newman 1963, p. 44.

- ^ Bliss 2004, p. 178.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 293.

- ^ Bliss 2004, p. 188.

- ^ a b Newman 1963, p. 47.

- ^ a b c Stursberg 1975, p. 59.

- ^ Newman 1963, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 218.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 219–223.

- ^ Regenstreif 1965, p. 26.

- ^ a b Meisel 1962, p. 45.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Beck 1968, p. 296.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Meisel 1962, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 56.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 57.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, p. 38.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 59.

- ^ a b Meisel 1962, p. 60.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 61.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 62.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 190.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, p. 45.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Spencer 1994, p. 31.

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 294.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, p. 50.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 229.

- ^ a b Meisel 1962, p. 152.

- ^ a b c Newman 1963, p. 53.

- ^ a b Meisel 1962, p. 155.

- ^ a b Newman 1963, p. 51.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 156.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Newman 1963, p. 49.

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 298.

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 305.

- ^ Spencer 1994, p. 35.

- ^ Gould, Tom (May 24, 1957), "Diefenbaker draws 6,000 to meeting", The Vancouver Sun, p. 2

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 162.

- ^ Tompson 1967, pp. 515–516.

- ^ a b Smith 1995, p. 233.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 237.

- ^ a b Stursberg 1975, p. 58.

- ^ a b Spencer 1994, p. 30.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 181–182.

- ^ a b c Newman 1963, p. 54.

- ^ a b Daniell, Raymond (April 27, 1957), "Canadian campaign begins in earnest", The New York Times, retrieved March 2, 2010 (fee for article)

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 168–169.

- ^ a b c Tompson 1967, p. 513.

- ^ Daniell, Raymond (May 14, 1957), "British Columbia is puzzle in vote", The New York Times, retrieved March 3, 2010 (fee for article)

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 159.

- ^ a b Beck 1968, p. 292.

- ^ a b c d Newman 1963, p. 55.

- ^ a b Stursberg 1975, p. 49.

- ^ King, Charles (June 8, 1957), "Violence and jeering mark PM's last rally", The Ottawa Citizen, retrieved March 3, 2010

- ^ a b Meisel 1962, p. 160.

- ^ Tompson 1967, pp. 516–517.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, p. 48.

- ^ ""Schoolboy prank" at rally termed "unfortunate" by PM", The Ottawa Citizen, June 8, 1957, retrieved March 3, 2010

- ^ Letter from J.G. Johnston to John Diefenbaker, June 10, 1957, on file with Diefenbaker Canada Centre, Saskatoon, SK, 1957 election files, pages no. 073862–073864

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 198.

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 248.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 201.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b c Meisel 1962, p. 220

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 223.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 224.

- ^ Long, Tania (May 12, 1957), "Canada exhibits election apathy", The New York Times, retrieved March 3, 2010 (fee for article)

- ^ Tompson 1967, p. 521.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 226.

- ^ a b c Beck 1968, p. 302.

- ^ a b c d e Meisel 1962, p. 163.

- ^ a b c d Stursberg 1975, p. 53.

- ^ Tompson 1967, p. 510.

- ^ Meisel 1962, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Daniell, Raymond (June 8, 1957), "Liberals expect losses in Ontario", The New York Times, retrieved March 3, 2010 (fee for article)

- ^ "Election prospects", Time, June 8, 1957, archived from the original on October 19, 2011, retrieved March 3, 2010

- ^ Beck 1968, p. 307.

- ^ Newman 1963, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b Newman 1963, p. 56.

- ^ Spencer 1994, p. 39.

- ^ a b Newman 1963, p. 57.

- ^ "Howe, Harris among nine ministers beaten", The Ottawa Citizen, June 11, 1957, retrieved March 5, 2010

- ^ a b Newman 1963, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 243.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 244.

- ^ a b Meisel 1962, p. 245.

- ^ A full description of the election in Yukon, the trial, and the subsequent by-election may be found in Erik Nielsen's memoir, The House Is Not a Home.

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Beck 1968, p. 300.

- ^ Regenstreif 1965, p. 29.

- ^ Tompson 1967, p. 519.

- ^ a b c Stursberg 1975, p. 73.

- ^ Newman 1963, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Stursberg 1975, p. 71.

- ^ Newman 1963, p. 65.

- ^ LeBlanc, John (June 11, 1957), "PC's smash long Liberal rule but lack clear-cut majority", The Ottawa Citizen, retrieved March 4, 2010

- ^ Cahill, Brian (June 11, 1957), "First they hardly believed; by midnight cabinet picked", The Montreal Gazette, retrieved March 13, 2010

- ^ Newman 1963, p. 63.

- ^ Newman 1963, p. 68.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 282.

- ^ Bliss 2004, p. 182.

- ^ a b c Meisel 1962, pp. 290–291.

Bibliography

edit- Beck, J. Murray (1968), Pendulum of Power: Canada's Federal Elections, Prentice-Hall of Canada

- Bliss, Michael (2004), Right Honourable Men: The Descent of Canadian Politics from Macdonald to Chrétien (revised ed.), HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., ISBN 0-00-639484-1

- Meisel, John (1962), The Canadian General Election of 1957, University of Toronto Press

- Newman, Peter (1963), Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years, McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 978-0-7710-6747-1

- Regenstreif, Peter (1965), Parties and Voting in Canada: The Diefenbaker Interlude, Longmans Canada

- Smith, Denis (1995), Rogue Tory: The Life and Legend of John Diefenbaker, Macfarlane Walter & Ross, ISBN 978-0-921912-92-7

- Spencer, Dick (1994), Trumpets and Drums: John Diefenbaker On the Campaign Trail, Greystone Books, ISBN 1-55054-168-4

- Stursberg, Peter (1975), Diefenbaker: Leadership Gained 1956–62, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-2130-4

- Tompson, Dale (1967), Louis St. Laurent: Canadian, Macmillan of Canada

Further reading

edit- Argyle, Ray (2004). Turning Points: The Campaigns that Changed Canada 2004 and Before. Toronto: White Knight Publications. ISBN 978-0-9734186-6-8.