The eastern wolf (Canis lycaon[5] or Canis lupus lycaon[6][7]), also known as the timber wolf,[8] Algonquin wolf and eastern timber wolf,[9] is a canine of debated taxonomy native to the Great Lakes region and southeastern Canada. It is considered to be either a unique subspecies of gray wolf or red wolf or a separate species from both.[10] Many studies have found the eastern wolf to be the product of ancient and recent genetic admixture between the gray wolf and the coyote,[11][12] while other studies have found some or all populations of the eastern wolf, as well as coyotes, originally separated from a common ancestor with the wolf over 1 million years ago and that these populations of the eastern wolf may be the same species as or a closely related species to the red wolf (Canis lupus rufus or Canis rufus) of the Southeastern United States.[13][14][10] Regardless of its status, it is regarded as unique and therefore worthy of conservation[15] with Canada citing the population in eastern Canada (also known as the "Algonquin wolf") as being the eastern wolf population subject to protection.[16]

| Eastern wolf | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Algonquin Provincial Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lycaon

|

| Binomial name | |

| Canis lycaon | |

| |

| Blue: Distribution of the Eastern wolf | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

There are two forms, the larger being referred to as the Great Lakes wolf, which is generally found in Minnesota, Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, southeastern Manitoba and northern Ontario, and the smaller being the Algonquin wolf, which inhabits eastern Canada, specifically central and eastern Ontario and southwestern Quebec, with some overlapping and mixing of the two types in the southern portions of northeastern and northwestern Ontario.[17][18][19] The eastern wolf's morphology is midway between that of the gray wolf and the coyote.[10] The fur is typically of a grizzled grayish-brown color mixed with cinnamon. The nape, shoulder and tail region are a mix of black and gray, with the flanks and chest being rufous or creamy.[18] It primarily preys on white-tailed deer, but may occasionally hunt moose and beavers.[20]

In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed the eastern wolf as a gray wolf subspecies,[6] which supports its earlier classification based on morphology in three studies.[21][22][23] This taxonomic classification has since been debated, with proposals based on DNA analyses that includes a gray wolf ecotype,[24] a gray wolf with genetic introgression from the coyote,[17] a gray wolf/coyote hybrid,[25] a gray wolf/red wolf hybrid,[23] the same species as the red wolf,[13] or a separate species (Canis lycaon) closely related to the red wolf.[13] Commencing in 2016, two studies using whole genome sequencing indicate that North American gray wolves and wolf-like canids were the result of ancient and complex gray wolf and coyote mixing,[11][12] with the Great Lakes wolf possessing 25% coyote ancestry and the Algonquin wolf possessing 40% coyote ancestry.[12]

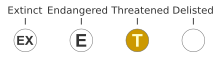

In the US, gray wolves including the timber wolf are protected under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, although the protections were removed at the federal level in 2021 before being reinstated in 2022.[26] In Canada, the eastern wolf is listed as Canis lupus lycaon under the Species At Risk Act 2002, Schedule 1 - List of Wildlife at Risk.[16] In 2015, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada recognized the eastern wolf in central and eastern Ontario and southwestern Quebec as Canis cf. lycaon (Canis species believed to be lycaon)[27] and a threatened species worthy of conservation.[28] The main threat to this wolf is human hunting and trapping outside of the protected areas, which leads to genetic introgression with the eastern coyote due to a lack of mates. Further human development immediately outside of the protected areas and the negative public perception of wolves are expected to inhibit any further expansion of their range.[28] In 2016, the Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario recognized the Algonquin wolf as a Canis sp. (Canis species) differentiated from the hybrid Great Lakes wolves which it found were the result of "hybridization and backcrossing among Eastern Wolf (Canis lycaon) (aka C. lupus lycaon), Gray Wolf (C. lupus), and Coyote (C. latrans)".[29]

Taxonomy

editThe first published name of a taxon belonging to the genus Canis from North America is Canis lycaon. It was published in 1775 by the German naturalist Johann Schreber, who had based it on the earlier description and illustration of one specimen that was thought to have been captured near Quebec. It was later reclassified as a subspecies of gray wolf by Edward Goldman.[30]

In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed the eastern wolf as a gray wolf subspecies,[6] which supports its earlier classification based on morphology in three studies.[21][22][23] This taxonomic classification has since been debated.

In 2021, the American Society of Mammalogists considered the eastern wolf as its own species (Canis lycaon).[5]

Taxonomic debate

editWhen European settlers first arrived to North America, the coyote's range was limited to the western half of the continent. They existed in the arid areas and across the open plains, including the prairie regions of the midwestern states. Early explorers found some in Indiana and Wisconsin. From the mid-1800s coyotes began expanding beyond their original range.[31]

The taxonomic debate regarding North American wolves can be summarised as follows:

There are two prevailing evolutionary models for North American Canis:

- (i) a two-species model

- that identifies grey wolves (C. lupus) and (western) coyotes (Canis latrans) as distinct species that gave rise to various hybrids, including the Great Lakes-boreal wolf (also known as Great Lakes wolf), the eastern coyote (also known as coywolf / brush wolf / tweed wolf), the red wolf and the eastern wolf;

or

- (ii) a three-species model

- that identifies the grey wolf, western coyote, and eastern wolf (C. lycaon) as distinct species, where Great Lakes-boreal wolves are the product of grey wolf × eastern wolf hybridization, eastern coyotes are the result of eastern wolf × western coyote hybridization, and red wolves are considered historically the same species as the eastern wolf, although their contemporary genetic signature has diverged owing to a bottleneck associated with captive breeding.[32]

The evolutionary biologist Robert K. Wayne, whose team is involved in an ongoing scientific debate with the team led by Linda K. Rutledge, describes the difference between these two evolutionary models: "In a way, it is all semantics. They call it a species, we call it an ecotype."[10]

Paleontological evidence

editSome of the earliest Canis specimens were discovered at Cripple Creek Sump, Fairbanks, Alaska, in strata dated 810,000 years old. The dental measurements of the specimens clearly match historical Canis lycaon specimens from Minnesota.[33]

Genetic evidence

editMitochondrial DNA (mDNA) passes along the maternal line and can date back thousands of years.[10]

In 1991, a study of the mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) sequences of wolves and coyotes from across North America found that the wolves of the Minnesota, Ontario and Quebec regions possessed coyote genotypes. The study proposes that dispersing male gray wolves were mating with coyote females in deforested areas bordering wolf territory. The distribution of coyote genotypes within wolves matched the phenotypic differences between these wolves found in an earlier study, with the larger Great Lakes wolf found in Minnesota, the smaller Algonquin (Provincial Park) type found in central Ontario, and the smallest and more coyote-like tweed wolf or eastern coyote type occupying sections of southeastern Ontario and southern Quebec.[17]

In 2000, a study looked at red wolves and eastern wolves from both eastern Canada and Minnesota. The study agreed that these two wolves readily hybridize with the coyote. The study used 8 microsatellites (genetic markers taken from across the genome of a specimen). The phylogenetic tree produced from the genetic sequences showed a close relationship among the red wolves and the eastern wolves from Algonquin Park, southern Quebec, and Minnesota such that they all clustered together. These then clustered next closer with the coyote and away from the gray wolf. A further analysis using mDNA sequences indicated the presence of coyote in both of these two wolves, and that these two wolves had diverged from the coyote 150,000–300,000 years ago. No gray wolf sequences were detected in the samples. The study proposed that these findings are inconsistent with the two wolves being subspecies of the gray wolf, that red wolves and eastern wolves (eastern Canadian and Minnesota) evolved in North America after having diverged from the coyote, and therefore they are more likely to hybridize with coyotes.[13]

In 2009, a study of eastern Canadian wolves – which was referred to as the "Great Lakes" wolf in this study – using microsatellites, mDNA, and the paternally-inherited yDNA markers found that the eastern Canadian wolf was a unique ecotype of the gray wolf that had undergone recent hybridization with other gray wolves and coyotes. It could find no evidence to support the findings of the earlier 2000 study regarding the eastern Canadian wolf. The study did not include the red wolf.[24] This study was quickly rebutted on the grounds that it had misinterpreted the findings of earlier studies that it relied upon, nor did it provide a definition for a number of the terms that it used, such as "ecotype".[34]

In 2011, a study compared the genetic sequences of 48,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (mutations) taken from the genomes of canids from around the world. The comparison indicated that the red wolf was about 76% coyote and 24% gray wolf with hybridization having occurred 287–430 years ago. The eastern wolf – which was referred to as the "Great Lakes" wolf in this study – was 58% gray wolf and 42% coyote with hybridization having occurred 546–963 years ago. The study rejected the theory of a common ancestry for the red and eastern wolves.[25][10] However the next year, a study reviewed a subset of the 2011 study's Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data and proposed that its methodology had skewed the results and that the eastern wolf is not a hybrid but a separate species.[14][10] The 2012 study proposed that there are three true canis species in North America – the gray wolf, the western coyote, and red wolf/eastern wolf with the eastern wolf represented by the Algonquin wolf, with the Great Lakes wolf being a hydrid of the eastern wolf and the gray wolf, and the eastern coyote being a hybrid of the western coyote and the eastern (Algonquin) wolf.[14]

Also in 2011, a scientific literature review was undertaken to help assess the taxonomy of North American wolves. One of the findings proposed was that the eastern wolf, whose range includes eastern Canada and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan plus Wisconsin and Minnesota is supported as a separate species by morphological and genetic data. Genetic data supports a close relationship between the eastern and red wolves, but not close enough to support these as one species. It was "likely" that these were the separate descendants of a common ancestor shared with coyotes. This review was published in 2012.[30]

Another study of both mDNA and yDNA in wolves and coyotes by the same authors indicates that the eastern wolf is genetically divergent from the gray wolf and is a North American evolved species with a long-standing history. The study could not dismiss the possibility of the eastern wolf having evolved from an ancient hybridization of gray wolf and coyote in the Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene.[35] Another study by the same authors found that eastern wolf mDNA genetic diversity had been lost after their culling in the early 1960s, leading to the invasion of coyotes into their territory and introgression of coyote mDNA.[36]

In 2014, the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis was invited by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to provide an independent review of its proposed rule relating to gray wolves. The Center's panel findings were that the proposed rule was heavily dependent upon the analysis contained in a scientific literature review conducted in 2011 (Chambers et al.), that this work was not universally accepted and that the issue was "not settled", and that the rule does not represent the "best available science".[37] Also in 2014, an experiment to hybridize a captive western gray wolf and a captive western coyote was successful, and therefore possible. The study did not assess the likelihood of such hybridization in the wild.[38]

In 2015, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada changed its designation of the eastern wolf from Canis lupus lycaon to Canis cf. lycaon (Canis species believed to be lycaon)[27] and a species at risk.[28]

Later that year, a study compared the DNA sequences using 127,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (mutations) of wolves and coyotes, but did not include red wolves and used Algonquin wolves as the representative eastern wolf, not wolves from the western Great Lakes states (usually referred to as Great Lakes wolves). The study indicated that Algonquin wolves were a distinct genomic cluster, even distinct from the Great Lakes states' wolves, which it found were actually hybrids of the gray wolf and the Algonquin wolf. The study's results did not exclude a possibility that the Great Lakes states' wolf (the gray wolf x eastern wolf hybrid (C. l. lycaon)) historically inhabited southern Ontario, southern Quebec and the northeastern United States alongside the Algonquin wolf, as there is evidence to suggest both inhabited those areas.[32]

In 2016, a study of mDNA once again indicated the Eastern wolf as a coyote–wolf hybrid.[39]

In 2018, a study looked at the Y-chromosome male lineage of canines. The unexpected finding was that the one Great Lakes wolf specimen included in this study showed a high degree of genetic divergence. Previous studies propose the Great Lakes wolf to be an ancient ecotype of the gray wolf that had experienced genetic introgression from other types of gray wolves and coyotes. The study called for further research into the Y-chromosomes of coyotes and wolves to ascertain if this is where this unique genetic male lineage may have originated from.[40]

Genomic evidence

editIn 2016, a whole-genome DNA study proposed, based on the assumptions made, that all of the North American wolves and coyotes diverged from a common ancestor less than 6,000–117,000 years ago, including the coyote diverging from Eurasian wolf about 51,000 years ago (which matches other studies indicating that the extant wolf came into being around this time), the red wolf diverging from the coyote between 55,000–117,000 years ago, and the eastern wolf (Great Lakes region and Algonquin) wolf diverging from the coyote 27,000–32,000 years ago, and asserts that these do not qualify as an ancient divergences that justify them being considered unique species.[11]

The study also indicated that all North America wolves have a significant amount of coyote ancestry and all coyotes some degree of wolf ancestry, and that the red wolf and eastern wolf are highly admixed with different proportions of gray wolf and coyote ancestry. The study found that coyote ancestry was highest in red wolves from the southeast of the United States and lowest among the Great Lakes wolves.[11]

The study also determined how unique each type of canids alleles were compared to Eurasian wolves, all of which had no coyote ancestry. It found the following proportion of unique alleles: coyotes 5.13% unique; red wolf 4.41%; Algonquin wolves 3.82%; Great Lakes wolves 3.61%; and gray wolves 3.3%. They asserted that the amount of unique alleles in all wolves was lower than expected and does not support an ancient (greater than 250,000 years) unique ancestry for any of the species.[11]

The authors contended that the proportion of unique alleles and ratio of wolf / coyote ancestry findings matched the south to north disappearance of the wolf due to European colonization since the 18th century and the resulting loss of habitat. Bounties led to the extirpation of wolves initially in the southeast, and as the wolf population declined wolf–coyote admixture increased. Later, this process occurred in the Great Lakes region and then eastern Canada with the influx of coyotes replacing wolves, followed by the expansion of coyotes and their hybrids. The Great Lakes and Algonquin wolves largely reflect lineages that have descendants in the modern wolf and coyote populations, but also reflect a distinct gray wolf ecotype which may have descendants in the modern wolf populations.[11]

As a result of these findings, the American Society of Mammalogists recognizes Canis lycaon as its own species.[5]

The proposed timing of the wolf/coyote divergence conflicts with the finding of a coyote-like specimen in strata dated to 1 million years before present.[41]

In 2017 a group of canid researchers challenged the 2016 whole-genome DNA study's finding that the red wolf and the eastern wolf were the result of recent coyote–gray wolf hybridization. The group asserts the three-year generation time used to calculate the divergence periods between different species was lower than empirical estimates of 4.7 years. The group also found deficiencies in the previous study's selection of specimens (two representative coyotes were from areas where recent coyote and gray wolf mixing with eastern wolves is known to have occurred), the lack of certainty in the ancestry of the selected Algonquin wolves, and the grouping of Great Lakes and Algonquin wolves together as eastern wolves, despite opposing genetic evidence. As well, they asserted the 2016 study ignored the fact that there is no evidence of hybridization between coyotes and gray wolves.[42]

The group also questioned the conclusions of genetic differentiation analysis in the study stating that results showing Great Lakes, Algonquin and red wolves, plus eastern coyotes differentiated from gray and Eurasian wolves were actually more consistent with an ancient hybridization or a distinct cladogenic origin for the red and Algonquin wolves than of a recent hybrid origin. The group further asserted that the levels of unique alleles for red and Algonquin wolves found the 2017 study were high enough to reveal a high degree of evolutionary distinctness. Therefore, the group argues that both the red wolf and the eastern wolf remain genetically distinct North American taxa.[42] This was rebutted by the authors of the earlier study.[43]

Wolf genome

editGenetic studies relating to wolves or dogs have inferred phylogenetic relationships based on the only reference genome available: that of the dog breed called the Boxer. In 2017, the first reference genome of the wolf Canis lupus lupus was mapped to aid future research.[44] In 2018, a study looked at the genomic structure and admixture of North American wolves, wolf-like canids, and coyotes using specimens from across their entire range that mapped the largest dataset of nuclear genome sequences and compared these against the wolf reference genome. The study supports the findings of previous studies that North American gray wolves and wolf-like canids were the result of complex gray wolf and coyote mixing. A polar wolf from Greenland and a coyote from Mexico represented the purest specimens. The coyotes from Alaska, California, Alabama, and Quebec show almost no wolf ancestry. Coyotes from Missouri, Illinois, and Florida exhibit 5–10% wolf ancestry. There was 40%:60% wolf to coyote ancestry in red wolves, 60%:40% in eastern wolves, and 75%:25% in the Great Lakes wolves. There was 10% coyote ancestry in Mexican wolves, 5% in Pacific Coast and Yellowstone wolves, and less than 3% in Canadian archipelago wolves.[12]

The study indicates that the genomic ancestry of red, eastern and Great Lakes wolves were the result of admixture between modern gray wolves and modern coyotes. This was then followed by development into local populations. Individuals within each group showed consistent levels of coyote to wolf inheritance, indicating that this was the result of relatively ancient admixture. The eastern wolf as found in Algonquin Provincial Park is genetically closely related to the Great Lakes wolf as found in Minnesota and Isle Royale National Park in Michigan. If a third canid had been involved in the admixture of the North American wolf-like canids, then its genetic signature would have been found in coyotes and wolves, which it has not.[12]

Later in 2018, a study based on a much smaller sample of 65,000 SNPs found that although the eastern wolf carries regional gray wolf and coyote alleles (gene variants), it also exhibits some alleles that are unique and therefore worthy of conservation.[15]

In 2023, a genomic study indicates that eastern wolves have evolved separately from grey wolves for the past 67,000 years and had experienced admixture with coyotes 37,000 years ago. The Great Lakes wolves were the result of admixture between eastern wolves and grey wolves 8,000 years ago. Eastern coyotes were the result of admixture between eastern wolves and "western" coyotes during the last century.[45]

Ancestor

editThe software that is currently used to conduct whole genome analysis for evidence of hybridization does not distinguish between past and present hybridization. In 2021, an mDNA analysis of modern and extinct North American wolf-like canines indicates that the extinct Late Pleistocene Beringian wolf was the ancestor of the southern wolf clade, which includes the Mexican wolf and the Great Plains wolf. The Mexican wolf is the most ancestral of the gray wolves that live in North America today. The modern coyote appeared around 10,000 years ago. The most genetically basal coyote mDNA clade pre-dates the Last Glacial Maximum and is a haplotype that can only be found in the Eastern wolf. This implies that the large, wolf-like Pleistocene coyote was the ancestor of the Eastern wolf. Further, another ancient haplotype detected in the Eastern wolf can be found only in the Mexican wolf. The authors propose that Pleistocene coyote and Beringian wolf admixture led to the Eastern wolf long before the arrival of the modern coyote and the modern wolf.[46]

Description and ecology

editDescription

editCharles Darwin was told that there were two types of wolf living in the Catskill Mountains, one being a lightly-built, greyhound-like animal that pursued deer, and the other being a bulkier, shorter-legged wolf.[47][48] The eastern wolf's fur is typically of a grizzled grayish-brown coloration, mixed with cinnamon. The flanks and chest are rufous or creamy, while the nape, shoulder and tail region are a mix of black and gray. Unlike gray wolves, eastern wolves rarely produce melanistic individuals.[18] The first documented all-black eastern wolf was found to have been an eastern wolf–gray wolf hybrid.[49] Like the red wolf, the eastern wolf is intermediate in size between the coyote and gray wolf, with females weighing 23.9 kilograms (53 lb) on average and males 30.3 kilograms (67 lb). Like the gray wolf, its average lifespan is 3–4 years, with a maximum of 15 years.[20] Their physical sizes that sets them intermediate between gray wolves and coyotes are actually believed to be more related to their adaptations to an environment with predominately medium-sized prey (similar to the case with the Mexican wolf in the southwestern US) rather than their close relationship to red wolves and coyotes.[24]

Ecology and behaviour

editThe eastern wolf primarily targets small to medium-sized prey items like white-tailed deer and beavers, unlike the gray wolf, which can effectively hunt large ungulates like caribou, elk, moose and bison.[49] Despite being carnivores, packs in Voyageurs National Park forage for blueberries in much of July and August, when the berries are in season. Packs carefully avoid each other; only lone wolves sometimes enter other packs' territories.[50] The average territory ranges 118–185 km2 (46–71 sq mi),[20] and the earliest age of dispersal for young eastern wolves is 15 weeks, much earlier than gray wolves.[49]

Distribution

editThe past range of the eastern wolf included southern Quebec, most of Ontario, the Great Lakes states, New York State and New England.[49] Today, the Great Lakes wolf is generally found in the northern halves of Minnesota and Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan,[51] southeastern Manitoba and northern Ontario,[19] and the Algonquin wolf inhabits central and eastern Ontario as well as southwestern Quebec north of the St. Lawrence River.[19][29] Algonquin wolves are particularly concentrated in Algonquin Provincial Park and other nearby protected areas, such as Killarney, Kawartha Highlands and Queen Elizabeth II Wildlands Provincial Parks and recent surveys also reveal small numbers of Algonquin wolves in the southern areas of northeastern Ontario and northwestern Ontario as far west as the Lake of the Woods near the border with Manitoba, where there is some mixing with Great Lakes wolves, and into southcentral Ontario, where there is some mixing with eastern coyotes.[19] There are some reports of eastern wolf sightings and of wolves being shot by hunters in Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River, New Brunswick, New York State, northern Vermont and Maine.[51][52][53][54] For example, DNA results of a canid killed near Cherry Valley, New York, in 2021 initially pointed to it being an eastern coyote, but a recent statement by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) confirms the animal was a wolf, with most of its ancestry matching wolves in Michigan; the DEC also has not confirmed or denied a breeding population within the state. Certain proponents of wolf recolonization state that wolves are already established in New York and New England, and have naturally dispersed from Canada by crossing the frozen St. Lawrence River.[55]

History, hybridization and conservation

editMitochondrial DNA indicates that before the arrival of Europeans, eastern wolves may have numbered at 64,500 to 90,200 individuals.[36] In 1942 it was believed that, before European settlement, the wolf had ranged throughout the wooded and open areas of eastern North America from what is now southern Quebec westward to the Great Plains and towards the Southeastern Woodlands (the southern extent was uncertain, but was believed to around what is now Kentucky, Tennessee and North Carolina).[56] The region's indigenous human populations did not fear eastern wolves, though they did occasionally catch them in traps, and their bones occur in native shell heaps.[56]

Early European settlers often kept their livestock on eastern wolf-free outer islands, though animals kept in pasture on the mainland were vulnerable, to the point that a campaign against eastern wolves was launched in the early years of the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies, in which both settlers and natives participated. A bounty system was put into effect, offering higher rewards for adult wolves, with their heads exposed on hooks in meetinghouses. Nevertheless, wolves were still plentiful enough in New England in the early 18th century to warrant the settlers of Cape Cod discussing the building of a high fence between Sandwich and Wareham to keep them out of grazing lands. The scheme failed, though the settlers continued to utilize wolf pits, a wolf trapping technique learned from the region's indigenous peoples. Eastern wolf numbers declined noticeably shortly before and after the American Revolution, particularly in Connecticut, where the wolf bounty was repealed in 1774. Eastern wolf numbers, however, were still high enough to cause concern in the more sparsely populated areas of southern New Hampshire and Maine, with wolf hunting becoming a regular occupation among settlers and natives alike. By the early 19th century, few eastern wolves remained in southern New Hampshire and Vermont.[56]

Prior to the establishment of Algonquin Provincial Park in 1893, the eastern wolf was common in central Ontario and the Algonquin Highlands. It continued to persist throughout the late 1800s, despite extensive logging and efforts by park rangers to eliminate it, largely due to the sustaining influence of plentiful prey items like deer and beaver. By the mid-1900s, there were as many as 55 eastern wolf packs in the park,[57] with an average of 49 wolves being killed annually during 1909–1958, until they were given official protection by the Ontario government in 1959, by which time the eastern wolf population in and around the park had been reduced to 500–1,000 individuals.[36][57] Nevertheless, during 1964–1965, 36% of the park's wolf population was culled by researchers trying to understand the reproduction and age structure of the population. This cull coincided with the expansion of coyotes into the park, and lead to an increase in eastern wolf–coyote hybridization.[36] Introgression of gray wolf genes into the eastern wolf population also occurred across northern and eastern Ontario, into Manitoba and Quebec, as well as into the western Great Lakes states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.[49] Despite protection within the park boundaries, there was a population decline in the east side of the park during 1987–1999, with an estimated number of 30 packs by 2000. This decline exceeded annual recruitment, and was attributed to human-caused mortality, which mostly occurred when dispersing animals left the park in search of deer during the winter months, and when pack ranges overlapped with park boundaries.[57] By 2001, protection was extended to eastern wolves occurring in the outskirts of the park. By 2012, the genetic composition of the park's eastern wolves was roughly restored to what it was in the mid-1960s than in the 1980s–1990s, when the majority of wolves had large amounts of coyote DNA.[36]

In 2013, an experiment which produced hybrids of coyotes and northwestern gray wolves in captivity using artificial insemination contributed more information to the controversy surrounding the eastern wolf's taxonomy. The purpose of this project was to determine whether the female western coyotes are capable of bearing hybrid western gray wolf-coyote pups, as well as to test the hybrid theory surrounding the origin of the eastern wolves. The resulting six hybrids produced in this captive artificial breeding were later transferred to the Wildlife Science Center of Forest Lake in Minnesota, where their behaviors were studied.[38]

Relationships with humans

editIn Algonquin folklore

editThe wolf is prominently portrayed in Algonquin mythology, where it is referred to as ma-hei-gan or nah-poo-tee in the Algonquian languages. It is the spirit brother of the Algonquian folk hero Nanabozho, and assisted him in several of his adventures, including thwarting the plots of the malicious anamakqui spirits and assisting him in recreating the world after a worldwide flood.[58]

Howling

editSince the discovery in 1963 that eastern wolves answered human imitations of their howls, Algonquin Provincial Park began its Public Wolf Howls attraction,[59] where as many as 2,500 visitors are led on expeditions into areas where eastern wolves were sighted the night before and listen to them answering the park staff's imitation howls. By 2000, 85 Public Wolf Howls had been held, with over 110,000 people having participated. The park considers the attraction as the cornerstone of its wolf education program and credits it with changing public attitudes towards wolves in Ontario.[57]

Attacks on humans

editSince the early 1970s, there have been several incidents of bold or aggressive behavior towards humans in Algonquin Provincial Park. Between 1987 and 1996, there were four instances of wolves biting people. The most serious case occurred in 1998 when a male wolf that had been long noted to be unafraid of humans stalked a couple walking their four-year-old daughter in September that year, losing interest when the family took refuge in a trailer. Two days later, the wolf attacked a 19-month-old boy, causing several puncture wounds on his chest and back before being driven off by campers. After the animal was killed later that day, it was found to not be rabid.[60]

References

edit- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Algoquin wolf". ontario.ca.

- ^ "Eastern wolf". www.thelandbetween.ca/the-land-between-species-at-risk.

- ^ Schreber, J. C. D. von. 1775. Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen, Zweiter Teil. Erlangen, Bavaria, pl. 89. [The mammals in illustrations after the nature with descriptions]

- ^ a b c "Mammal Diversity Database". American Society of Mammalogists. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Roskov Y.; Abucay L.; Orrell T.; et al., eds. (May 2018). "Canis lupus lycaon Schreber, 1775". Catalogue of Life 2018 Checklist. Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Mech, L. David; Frenzel, L. D. Jr (1971). "Ecological studies of the timber wolf in Northeastern Minnesota. Research Paper NC-52". Research Paper Nc-52. St. Paul, Mn: U.S. Dept. Of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station. 52. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station.

- ^ US Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992 Recovery Plan for the Eastern Timber Wolf. Twin Cities Minnesota. 73 pp.

- ^ a b c d e f g Beeland, T. (2013). "8-Tracing the Origins of Red Wolves". The Secret World of Red Wolves: The Fight to Save North America's Other Wolf. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 105–123. ISBN 978-1-4696-0199-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Vonholdt, B. M.; Cahill, J. A.; Fan, Z.; Gronau, I.; Robinson, J.; Pollinger, J. P.; Shapiro, B.; Wall, J.; Wayne, R. K. (2016). "Whole-genome sequence analysis shows that two endemic species of North American wolf are admixtures of the coyote and gray wolf". Science Advances. 2 (7): e1501714. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1714V. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501714. PMC 5919777. PMID 29713682.

- ^ a b c d e Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Gopalakrishan, Shyam; Vieira, Filipe G.; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Raundrup, Katrine; Heide Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Meldgaard, Morten; Petersen, Bent; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Mikkelsen, Johan Brus; Marquard-Petersen, Ulf; Dietz, Rune; Sonne, Christian; Dalén, Love; Bachmann, Lutz; Wiig, Øystein; Hansen, Anders J.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2018). "Population genomics of grey wolves and wolf-like canids in North America". PLOS Genetics. 14 (11): e1007745. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007745. PMC 6231604. PMID 30419012.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Paul J; Grewal, Sonya; Lawford, Ian D; Heal, Jennifer NM; Granacki, Angela G; Pennock, David; Theberge, John B; Theberge, Mary T; Voigt, Dennis R; Waddell, Will; Chambers, Robert E; Paquet, Paul C; Goulet, Gloria; Cluff, Dean; White, Bradley N (2000). "DNA profiles of the eastern Canadian wolf and the red wolf provide evidence for a common evolutionary history independent of the gray wolf". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 78 (12): 2156. doi:10.1139/z00-158.

- ^ a b c Rutledge, Linda Y.; Wilson, Paul J.; Klütsch, Cornelya F.C.; Patterson, Brent R.; White, Bradley N. (2012). "Conservation genomics in perspective: A holistic approach to understanding Canis evolution in North America" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 155: 186–192. Bibcode:2012BCons.155..186R. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.05.017. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ^ a b Heppenheimer, Elizabeth; Harrigan, Ryan J.; Rutledge, Linda Y.; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Decandia, Alexandra L.; Brzeski, Kristin E.; Benson, John F.; Wheeldon, Tyler; Patterson, Brent R.; Kays, Roland; Hohenlohe, Paul A.; von Holdt, Bridgett M. (2018). "Population Genomic Analysis of North American Eastern Wolves (Canis lycaon) Supports Their Conservation Priority Status". Genes. 9 (12): 606. doi:10.3390/genes9120606. PMC 6316216. PMID 30518163.

- ^ a b "List of Wildlife Species at Risk" (PDF). Laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Lehman, Niles; Eisenhawer, Andrew; Hansen, Kimberly; Mech, L. David; Peterson, Rolf O; Gogan, Peter J. P; Wayne, Robert K (1991). "Introgression of Coyote Mitochondrial Dna into Sympatric North American Gray Wolf Populations". Evolution. 45 (1): 104–119. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb05270.x. PMID 28564062.

- ^ a b c Thiel, R. P. & Wydeven, A. P. (2012). Eastern Wolf (Canis lycaon) Status Assessment Report: Covering East-Central North America Archived 2019-01-10 at the Wayback Machine, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- ^ a b c d "OWS". Wolvesontario.org. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Theberge, J. B. & M. T. Theberge (2004). The wolves of Algonquin Park, a 12 Year Ecological Study Archived 2018-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Geography, Publication Series Number 56, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario

- ^ a b Goldman, E. A. (1937). "The Wolves of North America". Journal of Mammalogy. 18 (1): 37–45. doi:10.2307/1374306. JSTOR 1374306.

- ^ a b Goldman EA. 1944. Classification of wolves: part II. Pages 389– 636 in Young SP, Goldman EA, editors. The wolves of North America. Washington, D.C.: The American Wildlife Institute.

- ^ a b c Nowak, Ronald M. (2002). "The Original Status of Wolves in Eastern North America". Southeastern Naturalist. 1 (2): 95–130. doi:10.1656/1528-7092(2002)001[0095:tosowi]2.0.co;2. S2CID 43938625.

- ^ a b c Koblmüller, S.; Nord, M.; Wayne, R. K. & Leonard, J. A. (2009). "Origin and status of the Great Lakes wolf" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 18 (11): 2313–2326. Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.2313K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2009.04176.x. hdl:10261/58581. PMID 19366404. S2CID 1090307.

- ^ a b Vonholdt, Bridgett M; Pollinger, John P; Earl, Dent A; Knowles, James C; Boyko, Adam R; Parker, Heidi; Geffen, Eli; Pilot, Malgorzata; Jedrzejewski, Wlodzimierz; Jedrzejewska, Bogumila; Sidorovich, Vadim; Greco, Claudia; Randi, Ettore; Musiani, Marco; Kays, Roland; Bustamante, Carlos D; Ostrander, Elaine A; Novembre, John; Wayne, Robert K (2011). "A genome-wide perspective on the evolutionary history of enigmatic wolf-like canids". Genome Research. 21 (8): 1294–305. doi:10.1101/gr.116301.110. PMC 3149496. PMID 21566151.

- ^ "Endangered Species Act: 2022 update". International Wolf Center. 29 December 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Government of Canada - COSEWIC (2015). "Eastern wolf".

- ^ a b c Government of Canada - Species at Risk Public Registry (2015). "Eastern wolf". Archived from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ^ a b "Ontario Species at Risk Evaluation Report for Algonquin Wolf (Canis sp.)" (PDF). Cossaroagency.ca. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ a b Chambers, Steven M.; Fain, Steven R.; Fazio, Bud; Amaral, Michael (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna. 77: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Nowak, Ronald M. (1979). North American Quaternary Canis. 6. Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas. p. 106. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.4072. ISBN 978-0-89338-007-6. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ a b L. Y. Rutledge; S. Devillard; J. Q. Boone; P. A. Hohenlohe; B. N. White (July 2015). "RAD sequencing and genomic simulations resolve hybrid origins within North American Canis". Biology Letters. 11 (7): 20150303. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0303. PMC 4528444. PMID 26156129.

- ^ Tedford, Richard H.; Wang, Xiaoming; Taylor, Beryl E. (2009). "Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae)" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 325: 1–218. doi:10.1206/574.1. hdl:2246/5999. S2CID 83594819.

- ^ Cronin, Matthew A; Mech, L. David (2009). "Problems with the claim of ecotype and taxon status of the wolf in the Great Lakes region". Molecular Ecology. 18 (24): 4991–3, discussion 4994–6. Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.4991C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04431.x. PMID 19919590. S2CID 1004770.

- ^ Wilson, Paul J.; Rutledge, Linda Y.; Wheeldon, Tyler J.; Patterson, Brent R.; White, Bradley N. (2012). "Y-chromosome evidence supports widespread signatures of three-species Canis hybridization in eastern North America". Ecology and Evolution. 2 (9): 2325–2332. Bibcode:2012EcoEv...2.2325W. doi:10.1002/ece3.301. PMC 3488682. PMID 23139890.

- ^ a b c d e Rutledge, Linda Y.; White, Bradley N.; Row, Jeffrey R.; Patterson, Brent R. (2012). "Intense harvesting of eastern wolves facilitated hybridization with coyotes". Ecology and Evolution. 2 (1): 19–33. Bibcode:2012EcoEv...2...19R. doi:10.1002/ece3.61. PMC 3297175. PMID 22408723.

- ^ Dumbacher, J., Review of Proposed Rule Regarding Status of the Wolf Under the Endangered Species Act, NCEAS (January 2014)

- ^ a b Mech, L. D.; Christensen, B. W.; Asa, C. S.; Callahan, M.; Young, J. K. (2014). "Production of Hybrids between Western Gray Wolves and Western Coyotes". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e88861. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...988861M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088861. PMC 3934856. PMID 24586418.

- ^ Ersmark, Erik; Klütsch, Cornelya F. C.; Chan, Yvonne L.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Fain, Steven R.; Illarionova, Natalia A.; Oskarsson, Mattias; Uhlén, Mathias; Zhang, Ya-Ping; Dalén, Love; Savolainen, Peter (2016). "From the Past to the Present: Wolf Phylogeography and Demographic History Based on the Mitochondrial Control Region". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00134.

- ^ Oetjens, Matthew T; Martin, Axel; Veeramah, Krishna R; Kidd, Jeffrey M (2018). "Analysis of the canid Y-chromosome phylogeny using short-read sequencing data reveals the presence of distinct haplogroups among Neolithic European dogs". BMC Genomics. 19 (1): 350. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4749-z. PMC 5946424. PMID 29747566.

- ^ Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H. (2008). Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13528-3. OCLC 185095648.

- ^ a b Paul A. Hohenlohe; Linda Y. Rutledge; Lisette P. Waits; Kimberly R. Andrews; Jennifer R. Adams; Joseph W. Hinton; Ronald M. Nowak; Brent R. Patterson; Adrian P. Wydeven; Paul A. Wilson; Brad N. White (2017). "Comment on "Whole-genome sequence analysis shows two endemic species of North American wolf are admixtures of the coyote and gray wolf"". Science Advances. 3 (6): e1602250. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E2250H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1602250. PMC 5462499. PMID 28630899.

- ^ Vonholdt, Bridgett M.; Cahill, James A.; Gronau, Ilan; Shapiro, Beth; Wall, Jeff; Wayne, Robert K. (2017). "Response to Hohenloheet al". Science Advances. 3 (6): e1701233. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E1233V. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1701233. PMC 5462503. PMID 28630935.

- ^ Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Kuderna, Lukas F. K.; Räikkönen, Jannikke; Petersen, Bent; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Hansen, Anders J.; Dalén, Love; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2017). "The wolf reference genome sequence (Canis lupus lupus) and its implications for Canis spp. Population genomics". BMC Genomics. 18 (1): 495. doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3883-3. PMC 5492679. PMID 28662691.

- ^ Vilaca S.T. (2023). "Tracing Eastern Wolf Origins From Whole-Genome Data in Context of Extensive Hybridization". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 40 (4): msad055. doi:10.1093/molbev/msad055. PMC 10098045. PMID 37046402.

- ^ Wilson, Paul J.; Rutledge, Linda Y. (2021). "Considering Pleistocene North American wolves and coyotes in the eastern Canis origin story". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (13): 9137–9147. Bibcode:2021EcoEv..11.9137W. doi:10.1002/ece3.7757. PMC 8258226. PMID 34257949.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1859). "(NY Times copy)" (PDF). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.). London, UK: John Murray. pp. 318–319. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Bennett, Alfred W. (22 February 1872). "[review] The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection; or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life; 6th ed". Books Received. Nature. 5 (121): 318–319. Bibcode:1872Natur...5..318B. doi:10.1038/005318a0. PMC 5184128. PMID 30164232.

- ^ a b c d e Rutledge, L.Y. (2010). Evolutionary origins, social structure, and hybridization of the eastern wolf (Canis lycaon) (Thesis). Peterborough, Ontario, Canada: Trent University.

- ^ Myers, John (5 December 2018). "Voyageurs National Park wolves eating beaver and blueberries, ..." Duluth News Tribune. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ a b "United States". Wolf.org. 9 August 2013.

- ^ "Adirondack Wolves - A Once-Extinct Species Returning To The Adirondacks". Adirondack.net.

- ^ "NY: If left protected, wolves could find way into Adirondacks". Timberwolfinformation.org. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "Wolf shot in New Brunswick was wild, tests confirm". CBC News. January 29, 2013. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ Board, Times Union Editorial (29 September 2022). "Editorial: Who's afraid of the New York wolf?". Times Union. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Glover, A. (1942), Extinct and vanishing mammals of the western hemisphere, with the marine species of all the oceans, American Committee for International Wild Life Protection, pp. 210–217.

- ^ a b c d Algonquin Wolf Advisory Group (2000). The Wolves of Algonquin Provincial Park: A Report to the Minister of Natural Resources, Algonquin Wolf Advisory Group, Ontario

- ^ Young, E. R. (1903). Algonquin Indian Tales, New York : Eaton & Mains; Cincinnati, Jennings & Pye.

- ^ Public Wolf Howls attraction

- ^ McNay, Mark E. (2002). A Case History of Wolf–Human Encounters in Alaska and Canada. Alaska Department of Fish and Game Wildlife Technical Bulletin. Retrieved on 2013-10-09.

Further reading

edit- Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. (2018). DRAFT Recovery Strategy for the Algonquin Wolf in Ontario Archived 2020-07-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- Pimlott, D. H., Shannon, J. A. & Kolenosky, G. B. (1969). "The ecology of the timber wolf in Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario", Research Report (Wildlife), no. 87. Ontario, Department of Lands and Forests, Toronto, Ontario

- Rutledge, L., The Eastern Wolf: What we do and do not know..., Wolf Steward (April 2010)

- Theberge, J. & Theberge, M. (2013). Wolf Country: Eleven Years Tracking the Algonquin Wolves, Random House LLC

External links

edit- Eastern wolf Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Wolf and Coyote DNA Bank @ Trent University

- Eastern wolf survey