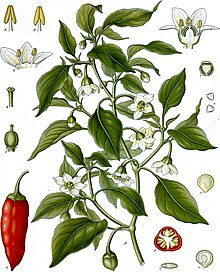

Capsicum annuum, commonly known as paprika, chili pepper, red pepper, sweet pepper, jalapeño, cayenne, or bell pepper,[5] is a fruiting plant from the family Solanaceae (nightshades), within the genus Capsicum which is native to the northern regions of South America and to southwestern North America. The plant produces berries of many colors including red, green, and yellow, often with pungent taste. It is also one of the oldest cultivated crops, with domestication dating back to around 6,000 years ago in regions of Mexico.[6] The genus Capsicum has over 30 species but Capsicum annuum is the primary species in its genus, as it has been widely cultivated for human consumption for a substantial amount of time and has spread across the world. This species has many uses in culinary applications, medicine, self defense, and can even be ornamental.[6]

| Capsicum annuum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Capsicum |

| Species: | C. annuum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Capsicum annuum | |

| Varieties and Groups | |

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

Name

editThe genus name Capsicum derives from a Greek-based derivative of the Latin word capto, meaning "to grasp, to seize", in reference to the heat or pungency of the species' fruit, although it has also been speculated to derive from the Latin word capsa, "box", referring to the shape of the fruit in forms of the typical species.[7] Although the species name annuum means "annual" (from the Latin annus , "year"), the plant is not an annual but is frost tender.[8] In the absence of winter frosts it can survive several seasons and grow into a large, shrubby perennial herb.[9]

Common names including the word "pepper" stem from a misconception on the part of Europeans taking part in the Columbian exchange. They mistakenly thought the spicy fruits were a variety of the black pepper plant, which also has spicy fruit. However, these two plants are not closely related.[10] Commonly used names for the fruit of Capsicum annuum in English vary by location and cultivar. The larger, sweeter cultivars are called "capsicum" in Australia and New Zealand.[11] In Great Britain and Ireland, cultivars of the plant are typically discussed in groups of either "sweet" or "hot/chilli" peppers, only rarely providing the specific cultivar.[12] In Canada and the United States it is commonplace to provide the cultivar in most instances, for example "bell", "jalapeño", "cayenne", or "bird's eye" peppers, to convey differences in taste including sweetness or pungency.[13]

Characteristics

editCapsicum annuum cultivars look like small shrubs with many branches and thin stems, with a tendency to climb, some varieties can grow up to two meters tall (6.56 feet) using others to climb on.[14] The shrub has oval glossy leaves sometimes growing to 7.5 cm (3 inches) in length, while generally green, depending on the cultivar the leaves can turn dark purple or black as the plant ages.[10] capsicum annuum are annual or biennial herbaceous plants that have a life cycle comprized of four stages (seedling, vegetation, flowering, and fruiting.)[15] Being a flowering plant with variations there are different shapes of flowers and fruits produced on individuals typically having star or bell shaped flowers coming in a range of colors including purple, white, and green. Just as the flowers, the fruits of this species comes in various shapes (berry shape to bell pepper shape), and colors including red, yellow, green, and black.[10]

Chiltepin pepper

editVariants of this species also have the ability to produce and retain capsaicinoid compounds giving their fruits a powerful (spicy) taste which can vary in strengths. One semi-domesticated variation of capsicum annuum is a variety named "Capsicum annuum L. var. glabriusculum" (Chiltepin peppers) Grows white flowers and produces berry fruits that are red when mature.[14] Similar to other variants the Chiltepin pepper produces and contains capsaicin which is responsible for its intense heat ranging from 100,000 to 200,000 Scoville heat units making it one of the hottest fruits grown in Mexico.[14]

Bell pepper

editAnother variant of Capsicum annuum, the bell pepper are quite different from Chiltepin peppers, being described as "sweet" as they do not contain high concentrations of capsaicin and are rated a 0 on the Scoville heat scale.[15] Bell peppers grow on shrub body plants, and the fruits are large, quadrangular, and fleshy. They can also grow to a weight of 500 grams and come in many colors including yellow, orange, red, and green.[16] Though this variant lacks in capsaicinoids, it is still packed with various bioactive compounds, carotinoids, and vitamins making them a valuable crop.[16]

Domestication

editCapsicum annuum today have many variations of fruits, the beginning to this is estimated to be from natives of Mesoamerica around 6,000 years ago using selective breeding to domesticate wild forms of the peppers. Through research scientists have found remnants of wild peppers ancestral to modern Capsicum annuum varieties in various locations and caves in places like Oaxaca Valley Mexico. The discovery of this has led researchers to believe that wild chili peppers were consumed before their domestication dating back to more than 8000 years ago.[6]

Domestication of crops using conscious and unconscious selective methods usually leads to a decrease in the plants natural defensive traits. However for Capsicum annuum this is not always true, some variants have been created to increase the defensive compound capsaicin otherwise making the fruit more powerful.[17] Capsicum annuum have also experienced "domestication syndrome" leading to several morphological and phytochemical changes leading to increased fruit and/or seed size, changes in reproductive cycles, and changes in plant structure. Though as a consequence of the cultivation of the wild species, some variants have experienced decreased fitness, leaving them vulnerable (and likely not to survive) when not being cultivated.[18]

Pollination

editFlowers of capsicum annuum generally consist of 6-7 petals and sepals, have 7 stamens, and contain an ovary that is superior to a single style consisting of 2-3 carpels and a single stamen. Members are self pollinators but cross pollination often occurs when plants are grown in large quantities, via bees, wasps, and ants.[6] In commercial production of capsicum annuum, human pollination is often used to produce hybrid seeds that can grow into new variants of the pepper, which is a form of selective breeding that demonstrates how the pepper was domesticated.[19]

Within the flowers there are several reproductive structures that are used in pollination and fertilization, the two relative include the anthers and the ovary. Anthers are the male organ producing the microgametes (pollen) that will disperse to fertilize the megagamete that is located in the ovary of the female reproductive organ, leading to the development of the propagule (Fruit).[20]

After fertilization the fruit of the plant begins to develop which is determined by the specific variety that is being grown. The fruit grows to maturity, then is ready for dispersal of its seeds.[6]

Seed dispersal

editThe seeds of some varieties of Capsicum annuum are coated in the compound capsaicin. This was a defensive mechanism of wild chilis before their domestication roughly 6000 years ago. Capsaicin is a compound that can be extremely powerful depending on the concentration, and this was used to protect the seeds from predation, and increase their chance of survival. However, birds are not affected by the presence of capsicum and are able to eat the fruits and seeds. The seeds are then passed through the birds’ digestive system and dispersed to new environments via defecation.[21]

Bird dispersal for seeds has proven to be beneficial for the peppers as they have the ability to spread large distances. One example of this is the wild chiltepin, which has a massive range of habitat from Northern Peru to Southwestern United States.[14]

Uses

editCapsicum annuum has been widely cultivated and modified through breeding for certain traits, which allows them to be used in multiple applications. These include in food, traditional medicine, cosmetics, and even self defense (pepper spray).[6]

Culinary

editThere are multiple ways this species can be used in food, this includes fresh, dried, pickled, and powdered. It is widely used in traditional Mexican cuisine to create dishes such as Oaxacan black mole.[6] It's added to many dishes worldwide for spice and flavor; it's used as a colorant for aesthetics.[citation needed] According to a study looking at capsicum annuum as a contender for alleviating micronutrient deficiencies, along with their flavor and coloring properties, they are also very rich in micronutrients, including vitamins: A, B, B3, C, and P.[22]

The species is a source of popular sweet peppers and hot chilis, with numerous varieties cultivated all around the world, and is the source of popular spices such as cayenne, chili, and paprika powders, as well as pimiento (pimento).

Capsinoid chemicals provide the distinctive tastes in C. annuum variants. In particular, capsaicin creates a burning sensation ("hotness"), which in extreme cases can last for several hours after ingestion. A measurement called the Scoville scale has been created to describe the hotness of peppers and other foods.

Traditional medicine

editIn old civilizations such as the Mayan and Aztec, capsicum species including C, Annuum. were used to treat many illnesses including asthma, toothaches, coughs, and sores. Today these practices still exist in developing countries, using them for their antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, and antiviral properties.[6] There have also been studies linking the consumption of capsaicinoids and a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer.[14]

Ornamental

editSome cultivars grown specifically for their aesthetic value include the U.S. National Arboretum's "Black Pearl"[23] and the "Bolivian Rainbow". Ornamental varieties tend to have unusually colored fruit and foliage with colors such as black and purple being notable. All are edible, and most (like "Royal Black") are hot. Certain cultivars of the New Mexico chile are commonly dried in ornamental arrangements known as ristras.

Pests

editEven with its defensive strategies, Capsicum annuum can still fall victim to several pests and viruses.[24] Some can harbor viruses deadly to the species, these include whiteflies and aphids. Another pest which is quite vicious is a weevil (Anthonomus eugenii Cano) which the larva of this pest affects the plants during the flowering and fruiting stages of its life, and can reduce its production rate by up to 90%.[25] Other pests that can cause damage to the plants are the tobacco budworms and thrips.[26] Diseases include phytophthora blight, anthracnose, phytophthora root and basal rot.[27]

Gallery

edit-

Capsicum annuum L var. fasciculatum Irish

-

Capsicum annuum L. var. fasciculatum Irish

-

Dried Capsicum annuum Red chili pepper

-

Capsicum annuum cultivars

-

Dried Guajillo chili pod

-

Typical Capsicum annuum flower, Royal Embers

-

Bolivian Rainbow with its fruits in different stages of ripeness

-

Capsicum annuum var. bola or ñora

-

Capsicum annuum Count Dracula

-

Dried Capsicum annuum Red chili pepper on Nanglo

-

Dried Capsicum annuum Red chili pepper

-

NuMex Memorial Day

-

Capsicum annuum Explosive Embers

-

Chili pepper 'subicho' seeds for planting

-

Bell pepper in Eastern Siberia

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Aguilar-Meléndez, A., Azurdia, C., Cerén-López, J., Menjívar, J. & Contreras, A. 2020. Capsicum annuum (amended version of 2019 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T100895534A172969027. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T100895534A172969027.en. Downloaded on 11 October 2021.

- ^ "Capsicum annuum". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ Minguez Mosquera M. I., Hornero Mendez D. (1994). "Comparative study of the effect of paprika processing on the carotenoids in peppers (Capsicum annuum) of the Bola and Agridulce varieties". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 42 (7): 1555–1560. doi:10.1021/jf00043a031.

- ^ "The Plant List".

- ^ Zhigila, Daniel Andrawus; AbdulRahaman, Abdullahi Alanamu; Kolawole, Opeyemi Saheed; Oladele, Felix A. (2014-02-17). "Fruit Morphology as Taxonomic Features in Five Varieties of Capsicum annuum L. Solanaceae". Journal of Botany. 2014: e540868. doi:10.1155/2014/540868. ISSN 2090-0120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h García-Gaytán, Víctor; Gómez-Merino, Fernando Carlos; Trejo-Téllez, Libia I.; Baca-Castillo, Gustavo Adolfo; García-Morales, Soledad (2017-03-19). "The Chilhuacle Chili (Capsicum annuum L.) in Mexico: Description of the Variety, Its Cultivation, and Uses". International Journal of Agronomy. 2017: e5641680. doi:10.1155/2017/5641680. ISSN 1687-8159.

- ^ "Capsicum annuum (bell pepper)". Cabi Compendium. CABI Compendium. 2022. doi:10.1079/cabicompendium.15784. S2CID 253616052.

- ^ "Peppers and chillies". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 21 Dec 2017.

- ^ Katzer, Gernot (May 27, 2008). "Paprika (Capsicum annuum L.)". Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Capsicum annuum - Britannica Encyclopedia". Britannica. 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Expat baffled by common Aussie supermarket item". news.com.au.

- ^ OxfordDictionaries.com, s.v.

- ^ "Bell and Chili Peppers". Agricultural Marketing Resource Center, US Department of Agriculture. 22 May 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Hayano-Kanashiro, Corina; Gámez-Meza, Nohemí; Medina-Juárez, Luis Ángel (January 2016). "Wild Pepper Capsicum annuum L. var. glabriusculum : Taxonomy, Plant Morphology, Distribution, Genetic Diversity, Genome Sequencing, and Phytochemical Compounds". Crop Science. 56 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2135/cropsci2014.11.0789. ISSN 0011-183X.

- ^ a b Nadeem, Muhammad (2011). "Antioxidant Potential of Bell Pepper (Capsicum annum L.)-A Review". Pakistan Journal of Food Sciences. 21 (1–4): 45–51 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ a b Anaya-Esparza, Luis Miguel; Mora, Zuamí Villagrán-de la; Vázquez-Paulino, Olga; Ascencio, Felipe; Villarruel-López, Angélica (January 2021). "Bell Peppers (Capsicum annum L.) Losses and Wastes: Source for Food and Pharmaceutical Applications". Molecules. 26 (17): 5341. doi:10.3390/molecules26175341. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC 8434037. PMID 34500773.

- ^ Noss, Clay F. (2014). "Does Gut Passage Affect Post-dispersal Seed Fate in a Wild Chili, Capsicum annuum?". Southeastern Naturalist. 13 (3): 475–483. doi:10.1656/058.013.0308. S2CID 84728663 – via google scholar.

- ^ Luna-Ruiz, Jose de Jesus; Nabhan, Gary P.; Aguilar-Meléndez, Araceli (2018). "Shifts in Plant Chemical Defenses of Chile Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Due to Domestication in Mesoamerica". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 6. doi:10.3389/fevo.2018.00048. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ Swamy, B. N.; Hedau, N. K.; G.v., Chaudhari; Kant, Lakshmi; Pattanayak, A. (2017-08-19). "CMS system and its stimulation in hybrid seed production of Capsicum annuum L." Scientia Horticulturae. 222: 175–179. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2017.05.023. ISSN 0304-4238.

- ^ Adhikari, Prakash B.; Liu, Xiaoyan; Wu, Xiaoyan; Zhu, Shaowei; Kasahara, Ryushiro D. (2020-05-01). "Fertilization in flowering plants: an odyssey of sperm cell delivery". Plant Molecular Biology. 103 (1): 9–32. doi:10.1007/s11103-020-00987-z. ISSN 1573-5028. PMID 32124177. S2CID 211730516.

- ^ Noss, Clay F. (2014). "Does Gut Passage Affect Post-dispersal Seed Fate in a Wild Chili, Capsicum annuum?". Southeastern Naturalist. 13 (3): 475–483. doi:10.1656/058.013.0308. S2CID 84728663 – via google scholar.

- ^ Olatunji, Tomi L.; Afolayan, Anthony J. (November 2018). "The suitability of chili pepper ( Capsicum annuum L.) for alleviating human micronutrient dietary deficiencies: A review". Food Science & Nutrition. 6 (8): 2239–2251. doi:10.1002/fsn3.790. ISSN 2048-7177. PMC 6261225. PMID 30510724.

- ^ "Capsicum annuum "Black Pearl"" (PDF). U.S. National Arboretum. March 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ Jo, Yeonhwa; Choi, Hoseong; Lee, Jeong Hun; Cho, Won Kyong; Moh, Sang Hyun (2022). "Viromes of 15 Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Cultivars". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (18): 10507. doi:10.3390/ijms231810507. PMC 9504177. PMID 36142418.

- ^ García-Gaytán, Víctor; Gómez-Merino, Fernando Carlos; Trejo-Téllez, Libia I.; Baca-Castillo, Gustavo Adolfo; García-Morales, Soledad (2017-03-19). "The Chilhuacle Chili (Capsicum annuum L.) in Mexico: Description of the Variety, Its Cultivation, and Uses". International Journal of Agronomy. 2017: e5641680. doi:10.1155/2017/5641680. ISSN 1687-8159.

- ^ Jo, Yeonhwa; Choi, Hoseong; Lee, Jeong Hun; Cho, Won Kyong; Moh, Sang Hyun (2022). "Viromes of 15 Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Cultivars". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (18): 10507. doi:10.3390/ijms231810507. PMC 9504177. PMID 36142418.

- ^ Mohammadbagheri, Leila; Nasr-Esfahani, Mehdi; Abdossi, Vahid; Naderi, Davood (2021-10-01). "Genetic diversity and biochemical analysis of Capsicum annuum (Bell pepper) in response to root and basal rot disease, Phytophthora capsici". Phytochemistry. 190: 112884. Bibcode:2021PChem.190k2884M. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112884. ISSN 0031-9422. PMID 34388481.

Further reading

edit- Malgorzata, Materska (March 2015). "Flavone C-glycosides from Capsicum annuum L.: relationships between antioxidant activity and lipophilicity". European Food Research and Technology. 240 (3): 549–557. doi:10.1007/s00217-014-2353-2.

- Arimboor, Ranjith; Natarajan, Ramesh Babu; Menon, K. Ramakrishna; Chandrasekhar, Lekshmi. P; Moorkoth, Vidya (March 2015). "Red pepper (Capsicum annuum) carotenoids as a source of natural food colors: analysis and stability-a review". Journal of Food Science and Technology. 52 (3): 1258–1271. doi:10.1007/s13197-014-1260-7. PMC 4348314. PMID 25745195.

External links

edit- Capsicum annuum in the CalPhotos photo database, University of California, Berkeley

- "Capsicum annuum". Calflora. Berkeley, California: The Calflora Database.

- "Capsicum annuum". Plants for a Future.