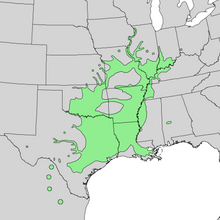

The pecan (/pɪˈkæn/ pih-KAN, also US: /pɪˈkɑːn, ˈpiːkæn/ pih-KAHN, PEE-kan, UK: /ˈpiːkən/ PEE-kən; Carya illinoinensis) is a species of hickory native to the Southern United States and northern Mexico in the region of the Mississippi River.[2]

| Pecan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Carya illinoinensis Morton Arboretum acc. 1082-39*3 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Juglandaceae |

| Genus: | Carya |

| Section: | Carya sect. Apocarya |

| Species: | C. illinoinensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carya illinoinensis | |

| |

| Natural range of Carya illinoinensis | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The tree is cultivated for its seed primarily in the U.S. states of Georgia,[3] New Mexico,[4] and Texas,[5] and in Mexico. The seed is an edible nut used as a snack and in various recipes, such as praline candy and pecan pie. The pecan is the state nut of Alabama, Arkansas, California, Texas, and Louisiana, and is also the state tree of Texas.

Name

editPecan derives from an Algonquian word variously referring to pecans, walnuts, and hickory nuts.[6] There are many pronunciations, some regional and others not.[7] There is little agreement in the United States regarding the "correct" pronunciation, even regionally.[8]

In 1927, the National Pecan Growers Association acknowledged variant pronunciations while designating one as official and correct: "pronounced as though spelled pea-con ... those in the habit of using any other pronunciation therefore be requested henceforth to adopt exclusively the pronunciation above specified above and hereby adopted by the Association."[9]

Description

editThe pecan tree is a large deciduous tree, growing to 20–40 m (66–131 ft) in height, rarely to 44 m (144 ft).[10] It typically has a spread of 12–23 m (39–75 ft) with a trunk up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) diameter. A 10-year-old sapling grown in optimal conditions will stand about 5 m (16 ft) tall. The leaves are alternate, 30–45 cm (12–18 in) long, and pinnate with 9–17 leaflets, each leaflet 5–12 cm (2–4+1⁄2 in) long and 2–6 cm (1–2+1⁄2 in) broad.[10]

A pecan, like the fruit of all other members of the hickory genus, is not truly a nut, but is technically a drupe, a fruit with a single stone or pit, surrounded by a husk. The husks are produced from the exocarp tissue of the flower, while the part known as the nut develops from the endocarp and contains the seed. The husk itself is aeneous, that is, brassy greenish-gold in color, oval to oblong in shape, 2.6–6 cm (1–2+3⁄8 in) long, and 1.5–3 cm (5⁄8–1+1⁄8 in) broad. The outer husk is 3–4 mm (1⁄8–5⁄32 in) thick, starts out green, and turns brown at maturity, at which time it splits off in four sections to release the thin-shelled seed.[10][11][12][13]

Taxonomy

editCarya illinoinensis, is a member of the Juglandaceae family. Juglandaceae are represented worldwide by seven and ten extant genera and more than 60 species. Most of these species are concentrated in the Northern Hemisphere of the New World, but some can be found on every continent except Antarctica.

Phylogeny

editThe first fossil examples of Juglandaceae appear during the Cretaceous. Differentiation between the subfamilies of Engelhardioideae and Juglandioideae occurred during the early Paleogene, about 64 million years ago. Extant examples of Engelhardioideae are generally tropical and evergreen, while those of Juglandioideae are deciduous and found in more temperate zones.

The second major step in the development of pecan was a change from wind-dispersed fruits to animal dispersion. This dispersal strategy coincides with developing a husk around the fruit and a drastic change in the relative concentrations of fatty acids. The ratio of oleic to linoleic acids is inverted between wind- and animal-dispersed seeds.[14][15] Further differentiation from other species of Juglandaceae occurred about 44 million years ago during the Eocene. The fruits of the pecan genus Carya differ from those of the walnut genus Juglans only in the formation of the husk of the fruit. The husks of walnuts develop from the bracts, bracteoles and sepals, or sepals only. The husks of pecans develop from the bracts and the bracteoles only.[15]

Cultivation

editPecans are one of the most recently domesticated of the major crops. Although wild pecans were well known among native and colonial Americans as a delicacy, the commercial growth of pecans in the United States did not begin until the 1880s.[16] As of 2014, the United States produced an annual crop of 119.8 million kilograms (264.2 million pounds), with 75% of the total crop produced in Georgia, New Mexico, and Texas.[4] They can be grown from USDA hardiness zones approximately 5 to 9, and grow best where summers are long, hot and humid. The nut harvest for growers is typically around mid-October.

Outside the U.S., Mexico produces nearly half of the world's total, similar in volume to that of the U.S., together accounting for 93% of global production.[17] Pecan trees require large quantities of water during the growing season, and most orchards in the region use flood irrigation to optimize consumptive water use and production of mature pecans.[18] Generally, two or more trees of different cultivars must be present to pollinate each other.[19]

Choosing cultivars can be a complex practice, based on the Alternate Bearing Index (ABI) and their period of pollinating.[19] Commercial growers are most concerned with the ABI, which describes a cultivar's likelihood to bear on alternating years (index of 1.0 signifies the highest likelihood of bearing little to nothing every other year). The period of pollination groups all cultivars into two families: those that shed pollen before they can receive pollen (protandrous) and those that shed pollen after becoming receptive to pollen (protogynous).[20] State-level resources provide recommended varieties for specific regions.[21][22]

Native pecans in Mexico are adapted from zones 9 to 11.[23] Little or no breeding work has been done with these populations. A few selections from native stands have been made, such as Frutosa and Norteña, which are recommended for cultivation in Mexico.[24][25] Improved varieties recommended for cultivation in Mexico are USDA-developed cultivars. This represents a gap in breeding development given that native pecans can be cultivated at least down to the Yucatán peninsula while the USDA cultivars have chilling hour requirements greater than those occurring in much of the region.[26] Some regions of the U.S. such as parts of Florida and Puerto Rico are zone 10 or higher, and these regions have limited options for pecan cultivation. 'Western' is the only commonly available variety that can make a crop in low-chill zones.[27]

Breeding and selection programs

editActive breeding and selection is carried out by the USDA Agricultural Research Service with growing locations at Brownwood and College Station, Texas.[5] University of Georgia has a breeding program at the Tifton campus working on selecting pecan varieties adapted to subtropical Southeastern U.S. growing conditions.[3]

While selection work has been done since the late 19th century, most acreage of pecans grown today is of older cultivars, such as 'Stuart', 'Schley', 'Elliott', and 'Desirable', with known flaws, but also with known production potential. Cultivars such as 'Elliot' are increasing in popularity due to resistance to pecan scab.[28] The long cycle time for pecan trees plus financial considerations dictate that new varieties go through an extensive vetting process before being widely planted. Numerous varieties produce well in Texas, but fail in the Southeastern U.S. due to increased disease pressure. Selection programs are ongoing at the state level, with Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Missouri, New Mexico, and others having trial plantings.

Varieties adapted from the southern tier of states north through some parts of Iowa and even into southern Canada are available from nurseries. Production potential drops significantly when planted further north than Tennessee. Most breeding efforts for northern-adapted varieties have not been on a large enough scale to significantly affect production. Varieties that are available and adapted (e.g., 'Major', 'Martzahn', 'Witte', 'Greenriver', 'Mullahy', and 'Posey') in zones 6 and farther north are almost entirely selections from wild stands. 'Kanza', a northern-adapted release from the USDA breeding program, is a grafted pecan having high productivity and quality, and cold tolerance.[29]

Diseases, pests, and disorders

editPecans are subject to various diseases, pests, and physiological disorders that can limit tree growth and fruit production. These range from scab to hickory shuckworm to shuck decline.

Pecans are prone to infection by bacteria and fungi such as pecan scab, especially in humid conditions. Scab is the most destructive disease affecting pecan trees untreated with fungicides. Recommendations for preventive spray materials and schedules are available from state-level resources.

Various insects feed on the leaves, stems, and developing nuts. These include ambrosia beetles, twig girdlers, pecan nut casebearer, hickory shuckworm, phylloxera, curculio, weevils, and several aphid species.

In the Southeastern U.S., nickel deficiency in C. illinoinensis produces a disorder called "mouse-ear" in trees fertilized with urea.[30] Similarly, zinc deficiency causes rosetting of the leaves. Various other disorders are documented, including canker disease and shuck decline complex.[citation needed]

Uses

editPecan seeds are edible, with a rich, buttery flavor. They can be eaten fresh or roasted, or used in cooking,[31] particularly in sweet desserts, such as pecan pie, a traditional Southern U.S. dish. Butter pecan is also a common flavor in cookies, cakes, and ice creams. Pecans are a significant ingredient in American praline candy.[32] Other applications of cooking with pecans include pecan oil and pecan butter.

Pecan wood is used in making furniture and wood flooring,[33] as well as flavoring fuel for smoking meats, giving grilled foods a sweet and nutty flavor stronger than many fruit woods.[34]

Nutrition

edit| Nutritional value per 100 grams | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 2,889 kJ (690 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

13.86 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Starch | 0.46 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 3.97 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 9.6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

71.97 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 6.18 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 40.801 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 21.614 0.986 g 20.630 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

9.17 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 3.52 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[35] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[36] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A pecan nut is 4% water, 72% fat, 9% protein, and 14% carbohydrates. In a 100 g reference amount, pecans provide 690 calories and are a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of dietary fiber (38% DV), manganese (214% DV), magnesium (34% DV), phosphorus (40% DV), zinc (48% DV), and thiamine (57% DV). Pecans are a moderate source (10–19% DV) of iron and B vitamins. Pecan fat content consists principally of monounsaturated fatty acids, mainly oleic acid (57% of total fat), and the polyunsaturated fatty acid, linoleic acid (30% of total fat).

History

editBefore European settlement, pecans were widely consumed and traded by Native Americans. As a wild forage, the fruit of the previous growing season is commonly still edible when found on the ground.

Pecans first became known to Europeans in the 16th century. The first Europeans to come into contact with pecans were Spanish explorers in what is now Louisiana, Texas, and Mexico. These Spanish explorers called the pecan, nuez de la arruga, which roughly translates to "wrinkle nut". Because of their familiarity with the genus Juglans, these early explorers referred to the nuts as nogales and nueces, the Spanish terms for "walnut trees" and "fruit of the walnut". They noted the particularly thin shell and acorn-like shape of the fruit, indicating they were referring to pecans. The Spaniards took the pecan into Europe, Asia, and Africa in the 16th century.

In 1792, William Bartram reported in his botanical book, Travels, a nut tree, Juglans exalata that some botanists today argue was the American pecan tree. Still, others argue hickory, Carya ovata. Pecan trees are native to the United States, and writing about the pecan tree goes back to the nation's founders. Thomas Jefferson planted pecan trees, C. illinoinensis (Illinois nuts), in his nut orchard at his home, Monticello, in Virginia. George Washington reported in his journal that Thomas Jefferson gave him "Illinois nuts", pecans, which Washington then grew at Mount Vernon, his Virginia home.

Commercial production of pecans was slow because trees were slow to mature and bear fruit. More importantly, the trees grown from the nuts of one tree have very diverse characters. To speed nut production and retain the best tree characteristics, grafting from mature, productive trees was the apparent strategy. However, this proved technically challenging. The Centennial cultivar was the first to be successfully grafted. This was accomplished by an enslaved person called Antoine in 1846 or 1847, who was owned by Jacques Telesphore Roman of the Oak Alley Plantation near the Mississippi River. The scions were supplied by Dr. A. E. Colomb, who had unsuccessfully attempted to graft them.[37]

Genetics

editPecan is a 32-chromosome species (1N = 16) that readily hybridizes with other 32-chromosome members of the Carya genus, such as Carya ovata, Carya laciniosa, Carya cordiformis and has been reported to hybridize with 64-chromosome species such as Carya tomentosa. Most such hybrids are unproductive. Hybrids are referred to as "hicans" to indicate their hybrid origin.[38] Recent efforts at NMSU to complete a pecan genome showed that DNA introgressed from C. aquatica (water hickory), C. myristiciformis (nutmeg hickory), and C. cordiformis (bitternut hickory) is present in commercial pecan varieties grown today. [39]

In culture

editIn 1919, the 36th Texas Legislature made the pecan tree the state tree of Texas; in 2001, the pecan was declared the state's official "health nut", and in 2013, pecan pie was made the state's official pie.[40] The town of San Saba, Texas claims to be "The Pecan Capital of the World" and is the site of the "Mother Tree" (c. 1850) considered to be the source of the state's production through its progeny.[41][42]

Alabama named the pecan the official state nut in 1982.[43] Arkansas adopted it as the official nut in 2009.[44] California adopted it, along with the almond, pistachio, and walnut, as one of four state nuts in 2017.[45] Louisiana, known for pralines, adopted the Pecan as its official state nut in 2023.[46] In 1988, Oklahoma enacted an official state meal which included pecan pie.[47]

Gallery

edit-

Bud

-

A pecan sprouting

-

Immature pecan fruits

-

Ripe pecan nuts on tree

-

Carya illinoinensis, MHNT

-

Shelled and unshelled pecans

-

Pecan tree in Oklahoma loaded with fruits

-

A large pecan tree in Oklahoma

-

A Danish pastry topped with pecans and maple syrup

References

edit- ^ "Carya illinoinensis: Barstow, M.: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T62019622A62019624". IUCN. 2018-06-21. doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2018-2.rlts.t62019622a62019624.en. S2CID 242909.

- ^ a b "Carya illinoinensis". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ^ a b Conner, Patrick J (2018). "Pecan breeding". College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University of Georgia. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Pecans". Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. August 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ a b "USDA Pecan Breeding Program, National Clonal Germplasm Repository for Pecans and Hickories". Horticulture Dept. Retrieved 6 Dec 2017.

- ^ "Pecan, n." OED Online. Oxford University Press. March 2016. Archived from the original on December 6, 2018.

French (Mississippi Valley) pacane (1712; 1721 in the source translated in quot. 1761 at sense 1); Illinois pakani (/pakaːni/); cognates in other Algonquian languages are applied to hickory nuts and walnuts. Compare Spanish pacano (1772; 1779 in a Louisiana context).

- ^ See "Pecan" at Wiktionary.

- ^ Bert Vaux; Scott Golder (2003). "Dialect Survey Results". Harvard Dialect Survey. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ "Proceedings, 27th National Convention, National Pecan Growers Association (27-29 September 1927, Shreveport, LA)," 153. Also cited in "'Chattanooga Daily Times, 30 September 1927, 7 ("Pecan Growers Vote Nut’s Pronunciation").

- ^ a b c "Carya illinoinensis in Flora of North America @ efloras.org". www.efloras.org. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ "Carya illinoinensis, pecan". Oklahoma Biological Survey. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ "Carya fruits (hickory nuts)". Vanderbilt University. 2004-08-19. Archived from the original on 2004-08-19. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Collingwood, G. H., Brush, W. D., & Butches, D., eds. (1964). Knowing your trees. 2nd ed. American Forestry Association, Washington, DC.

- ^ Donald E. Stone; et al. (1969). "New World Juglandaceae. II. Hickory Nut Oils, Phenetic Similarities, and Evolutionary Implications in the Genus Carya". American Journal of Botany. 56 (8). Botanical Society of America: 928–935. doi:10.2307/2440634. JSTOR 2440634.

- ^ a b Manos, Paul; Stone, Donald E. (2001). "Evolution, Phylogeny, and Systematics of Juglandaceae" (PDF). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 88 (2). Missouri Botanical Garden Press: 231–269. doi:10.2307/2666226. JSTOR 2666226.

- ^ "Pecan kernel". Texas A&M University. 2006-08-18. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "2017 World Pecan Production". Pecan Report. 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Deb, S. K., Shukla, M. K., Šimůnek, J., & Mexal, J. G. (2013). Evaluation of Spatial and Temporal Root Water Uptake Patterns of a Flood-Irrigated Pecan Tree Using the HYDRUS (2D/3D) Model. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering, 139(8), 599–611. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)IR.1943-4774.0000611

- ^ a b "Pecan Breeding". University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Grauke, L. J. "Pecan flowering".

- ^ Pecan Breeding. "Cultivars - Recommended Cultivar List". pecanbreeding.uga.edu.

- ^ Stein & Kamas. "Improved Pecans" (PDF). aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu.

- ^ carya species. "gov/carya species/illinoinensis ilnatdis". cgru.usda.gov.

- ^ HORTSCIENCE. "'Norten˜a' Pecan" (PDF). hortsci.ashspublications.org.

- ^ Infap. "Tecnología de Producción en Nogal Pecanero" (PDF). biblioteca.inifap.gob.mx (in Spanish).

- ^ Smith, Michael W.; Carroll, Becky L.; Cheary, Becky S. (1 September 1992). "Chilling Requirement of Pecan". Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. pp. 745–748.

- ^ Grauke. "Pecan Cultivars-Western". cgru.usda.gov.

- ^ Conner, Patrick; Sparks, Darrell. "'Elliott' Pecan" (PDF). Department of Horticulture, University of Georgia. Retrieved Dec 6, 2017.

- ^ "Kanza, Cultivars". College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University of Georgia. 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Allen V. Barker; D. J. Pilbeam (2007). Handbook of plant nutrition. CRC Press. pp. 399–. ISBN 978-0-8247-5904-9. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ Elias, Thomas S.; Dykeman, Peter A. (2009) [1982]. Edible Wild Plants: A North American Field Guide to Over 200 Natural Foods. New York: Sterling. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-4027-6715-9. OCLC 244766414.

- ^ Greg Morago (18 December 2017). "Pecan pralines a sweet tradition (no matter how you say it)". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "Pecan". The Wood Database. 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Noma Nazish (17 April 2018). "Grill Gourmet: The Best Wood And Food Pairings To Try This Season". Forbes. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ Grauke, L J. "Pecan cultivars: Centennial". Pecan cultivars. USDA-ARS Pecan Genetics. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ Grauke, L. J. "Pecan, C. illinoenensis".

- ^ Randall, Jennifer; et al. (5 July 2021). "Four Chromosome Scale Genomes, C. illinoenensis". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 4125. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24328-w. PMC 8257795. PMID 34226565.

- ^ Texas State Symbols, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, August 30, 2017, retrieved 2019-05-15

- ^ "Town website for San Saba, Texas". Town of San Saba Texas.

- ^ Glentzer, Molly (July 12, 2001), "Pecan territory", Saveur, retrieved 2019-05-15

- ^ "Official Alabama Nut". Official Symbols and Emblems of Alabama. Alabama Department of Archives and History. February 6, 2014. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ Ware, David (March 8, 2018). "Official State Nut". The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. The Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ "State Symbols". State History. California Stale Library. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ Ryan, Molly (31 July 2023). "The beloved pecan is officially the state nut of Louisiana. Why now?". WWNO. NPR. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ Everett, Dianna, State Meal, Oklahoma Historical Society, retrieved 2019-05-15