The Diocese of Pittsburgh (Latin: Diœcesis Pittsburgensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical jurisdiction, or diocese, of the Catholic Church in Western Pennsylvania in the United States. It was established on August 11, 1843. The diocese is a suffragan diocese of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

Diocese of Pittsburgh Diœcesis Pittsburgensis | |

|---|---|

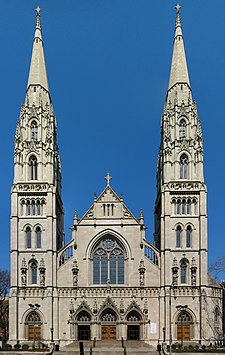

St. Paul Cathedral | |

Coat of Arms of the Diocese of Pittsburgh | |

| Location | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| Ecclesiastical province | Province of Philadelphia |

| Headquarters | 111 Boulevard of the Allies Pittsburgh, PA 15222 |

| Coordinates | 40°26′50″N 79°56′59″W / 40.44722°N 79.94972°W |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 3,786 sq mi (9,810 km2) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2021) 1,893,567 625,490 (33%) |

| Parishes | 107 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | August 11, 1843 |

| Cathedral | Saint Paul Cathedral |

| Patron saint | Mary Immaculate (primary) and St. Paul the Apostle (secondary)[1] |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | David Zubik |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | Nelson J. Perez |

| Auxiliary Bishops | William J. Waltersheid Mark Eckman |

| Vicar General | Lawrence A. DiNardo |

| Judicial Vicar | Michael S. Sedor |

| Bishops emeritus | William J. Winter |

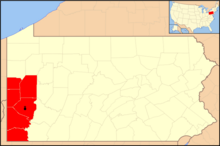

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| diopitt.org | |

The cathedral church of the diocese is Saint Paul Cathedral in Pittsburgh. As of 2024, the bishop of Pittsburgh is David Zubik.

Territory

editThe Diocese of Pittsburgh includes 61 parish-groupings (107 churches) in the counties of Allegheny, Beaver, Butler, Greene, Lawrence, and Washington, an area of 3,786 sq mi (9,810 km2). The diocese had a Catholic population of 625,490 as of 2022. As of July 2021, the diocese had 194 active priests.[2]

History

edit1750 to 1800

editIn 1754, the first mass within the present-day Diocese of Pittsburgh was celebrated at Fort Duquesne by a French Franciscan chaplain. A chapel was built at the fort, dedicated to the Virgin Mary under the title of "The Assumption of Our Lady of the Beautiful River". When the French destroyed the fort in 1758, the mission became a ruin.[3] The region then passed into British rule.

Unlike the other British colonies in America, the Province of Pennsylvania did not ban Catholics from the colony or threaten priests with imprisonment. However, the colony did require any Catholics seeing public office to take an oath to Protestantism. In 1784, a year after the end of the American Revolution, Pope Pius VI erected the Apostolic Prefecture of United States of America, including all of the new United States.[4][5]

In 1789, Pius VI converted the prefecture to the Diocese of Baltimore, covering all of the United States.[6] With the passage of the US Bill of Rights in 1791, Catholics received full freedom of worship.

1800 to 1850

editIn 1808, Pope Pius VII erected the Diocese of Philadelphia, covering all of Pennsylvania.[7] In 1843, the four American bishops and one archbishop met in the Fifth Provincial Council of Baltimore. They recommended that the Vatican erect a Diocese of Pittsburgh and nominated Michael O'Connor, vicar general of Western Pennsylvania and pastor of St. Paul's Church in Pittsburgh, to be appointed the first bishop.[8]

The Vatican erected the Diocese of Pittsburgh on August 11, 1843, by taking its territory from the Diocese of Philadelphia.[9] The new diocese covered all of Western Pennsylvania. The pope appointed O'Connor as bishop. After his consecration in Rome, O'Connor traveled to Ireland to recruit clergy for his new diocese. He found eight seminarians from Maynooth College in Maynooth and seven Sisters of Mercy from Dublin.[10] O'Connor arrived in Pittsburgh in December 1843.

In 1844, O'Connor founded a girls' academy and St. Paul's orphan asylum, a chapel for African Americans, the Pittsburgh Catholic and St. Michael's Seminary. To serve the German immigrants in his diocese, he welcomed the Benedictine monks, who founded Saint Vincent Archabbey in Latrobe,[8] the first Benedictine monastery in the United States. To further education he invited the Franciscan Brothers of Mountbellew in Ireland, who established the first community of religious brothers in the United States in Loretto.[11]

1850 to 1900

editIn 1853, the Vatican erected the Diocese of Erie, taking the northern counties from the Diocese of Pittsburgh. After O'Connor resigned in 1860, Pope Pius IX named Michael Domenec from Philadelphia as the second bishop of Pittsburgh.[12] After the American Civil War ended in 1865, the diocese went heavily in debt to finance expansion projects. When the panic of 1873 happened, diocesan revenues fell dramatically, creating a debt crisis for the diocese.[13]

In 1876, Pius IX erected the Diocese of Allegheny, taking several counties from the Diocese of Pittsburgh, and named Domenec as its first bishop. He was succeeded in Pittsburgh by John Tuigg of Pittsburgh.

During his tenure as bishop, Tuigg succeeded in stabilizing the diocesan finances. The Pittsburgh Catholic College of the Holy Ghost, the predecessor of Duquesne University, was founded in 1878 in Pittsburgh by a group of Holy Ghost priests from Germany.[14] After Tuigg suffered his first stroke, Pope Leo XIII appointed Richard Phelan of Pittsburgh as coadjutor bishop in 1885 to assist Tuigg.[15]

In July 1889, the Vatican reversed course, suppressed the Diocese of Allegheny and reintegrated all of its territory back into the Diocese of Pittsburgh.[10] After Tuigg died in December 1889, Phelan automatically succeeded him as bishop.[12] During this period, Catholic immigrants of many nationalities flooded into Western Pennsylvania to work the mines and steel mills. Phelan set up new parishes with pastors who could speak the immigrants' native languages.

1900 to 1980

editIn 1901, the Vatican erected the Diocese of Altoona, taking its territory from the Diocese of Pittsburgh. In 1903, Pope Pius X named Regis Canevin of Pittsburgh as coadjutor bishop in that diocese.[16] Canevin succeeded Phelan after his death in 1904.[10] Canevin died in 1921.[12]

Pope Benedict XV named Hugh Charles Boyle of Pittsburgh as the sixth bishop of that diocese in 1921.[12] During his 29-year tenure, Boyle sponsored a comprehensive school-building program in the diocese.[17] The Brothers of the Christian Schools opened Central Catholic High School in Pittsburgh in 1927.[18] The Sisters of Mercy opened Carlow College, a women's college, in Pittsburgh in 1929.[19]

In 1948, John Dearden of Pittsburgh was appointed coadjutor bishop of the diocese by Pope Pius XII to assist Boyle.[20] When Boyle died in 1950, Dearden automatically succeeded him as bishop.[12] The Vatican in 1951 erected the Diocese of Greensburg, taking its territory from the Diocese of Pittsburgh.[21] Dearden was appointed archbishop of the Archdiocese of Detroit in 1958

To replace Dearden, Pius XII named Bishop John Wright from the Diocese of Worcester.[12] Wright attended the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), during which he was a decisive force behind several of its documents.[22] Following the council's advancements in ecumenism, he believed that an "immediate unity in good works and charity" would arise between Catholics and Protestants.[23] In 1961, Wright opened the Bishop's Latin School in Pittsburgh as the pre-seminary high school of the diocese.[24][25] La Roche College was founded in McCandless, Pennsylvania, in 1963 by the Sisters of Divine Providence as a private college for religious sisters.[26]

Wright promoted music and culture during his time in Pittsburgh. He commissioned the composer Mary Lou Williams, to perform a jazz mass at a local Catholic school, and helped her to establish the Pittsburgh Jazz Festival. In 1969, Pope Paul VI appointed Wright as the prefect of the Congregation for the Clergy in Rome.[12]

The next bishop of Pittsburgh was Auxiliary Bishop Vincent Leonard of Pittsburgh, appointed by Paul VI in 1969. During his tenure, Leonard became one of the first American bishops to release his diocesan financial reports to the public. He also established a due-process system to allow Catholics to appeal any administrative decision they believed was a violation of canon law.[27]

1980 to 2000

editLeonard resigned as bishop of Pittsburgh in 1983, due to arthritis.[28] Pope John Paul II then named Auxiliary Bishop Anthony Bevilacqua of the Diocese of Brooklyn as the tenth bishop of Pittsburgh that same year.[12] In 1986, Bevilacqua banned women from participating in the Holy Thursday foot-washing service. He said that the service was a re-enactment of the Last Supper, in which Jesus only washed men's feet. After pushback from Catholic women and from the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, Bevilacqua relented, allowing individual pastors to decide. However, he refused to attend services that washed women's feet.[29] In 1987, John Paul II appointed Bevilacqua as archbishop of Philadelphia.

The next bishop of Pittsburgh was Auxiliary Bishop Donald Wuerl from the Archdiocese of Seattle, appointed by John Paul II in 1988.[12] Despite the financial condition of the diocese, Wuerl decided to expand health services. Wuerl worked with hospitals and community groups to create a group home for people suffering from HIV/AIDS. In 2003, Wuerl conducted a successful $2.5 million fundraising campaign to create the Catholic Charities Free Health Care Center. The clinic served the uninsured working poor.[30] Wuerl reorganized the diocese in response to demographic changes, the decline of the steel industry, and the church's weak financial position. He closed 73 church buildings, including 37 churches, and reduced 331 parishes to 214 parishes through mergers.[31] Wuerl was named archbishop of the Archdiocese of Washington in 2006.

2000 to present

editPope Benedict XVI appointed bishop David Zubik from the Diocese of Green Bay as the twelfth bishop of Pittsburgh in 2007.[12] In 2012, the diocese joined other parties in suing the Obama administration regarding the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA). The diocese objected to a regulation that would force Catholic hospitals and other such institutions to provide health insurance coverage of contraceptives to their employees. Zubik said, "The mandate would require the Catholic Church as an employer to violate its fundamental beliefs concerning human life and human dignity ..." These cases were consolidated and made it to the Supreme Court as Zubik v. Burwell.[32] The court vacated a lower court ruling and forced the cases back to the lower courts.

In 2015, Zubik announced On Mission for the Church ALIVE!, an initiative to start reorganizing parishes in 2018. The plan was to merge 188 parishes to 57 parish groupings served by clergy teams, with the goal of maximizing parish resources to achieve "vibrant parishes and effective ministries."[33] Zubik formulated the plan in response to decreasing mass attendance, a significant drop in offertory collections and a declining number of priests; by 2025 the diocese was projected to have a 50% drop in the number of priest from 2018.[34][35] Many parishioners were angry at the closing of churches they had attended since childhood. Others supported the plan, saying sweeping changes were necessary to keep the diocese healthy. Zubik in 2015 acknowledged that:

"...transformation is rarely easy, especially in the heartfelt matters of faith and parish life. I know that this change will require us – the faithful, the clergy, and myself – to let go of some things that are precious and familiar. I also am convinced that our clergy and faithful have what it takes to form deep and lasting relationships within their groupings and to create welcoming communities."[36]

Pope Francis in 2021 issued the motu proprio Traditionis custodes, an apostolic letter that increased restrictions on the celebration of the Tridentine Mass. The diocese announced that it would continue the daily celebration of the Tridentine Mass at Most Precious Blood of Jesus Parish in Pittsburgh. Zubik had established this personal parish in July 2019 for daily celebration of the Tridentine Mass.[37]

Bishops

editBishops of Pittsburgh

edit- Michael O'Connor (1843-7/1853), appointed Bishop of Erie

- Michael O'Connor (12/1853-1860)

- Michael Domenec (1860–1876), appointed Bishop of Allegheny

- John Tuigg (1876–1889)

- Richard Phelan (1889–1904; coadjutor bishop 1885–1889)

- Regis Canevin (1904–1921; coadjutor bishop 1903–1904), retired and appointed Archbishop ad personam

- Hugh Boyle (1921–1950)

- John Dearden (1950–1958; coadjutor bishop 1948–1950), appointed Archbishop of Detroit (elevated to Cardinal in 1969)

- John Wright (1959–1969), appointed Prefect of the Congregation for the Clergy (elevated to Cardinal in 1969)

- Vincent Leonard (1969–1983)

- Anthony Bevilacqua (1983–1987), appointed Archbishop of Philadelphia (elevated to Cardinal in 1991)

- Donald Wuerl (1988–2006), appointed Archbishop of Washington (elevated to Cardinal in 2010)

- David Zubik (2007–present)

Current auxiliary bishops

edit- William J. Waltersheid (2011–present)

- Mark Eckman (2022–present)

Former auxiliary bishops

edit- Coleman F. Carroll (1953–1958), appointed Bishop of Miami and subsequently elevated to archbishop of the same see

- Vincent Martin Leonard (1964–1969), appointed Bishop of Pittsburgh

- John Bernard McDowell (1966–1996)

- Anthony G. Bosco (1970–1987), appointed Bishop of Greensburg

- William J. Winter (1989–2005)

- Thomas J. Tobin (1992–1996), appointed Bishop of Youngstown and later Bishop of Providence

- David Zubik (1997–2003), appointed Bishop of Green Bay and later Bishop of Pittsburgh

- Paul J. Bradley (2004–2009), appointed Bishop of Kalamazoo

Other diocesan priests who became bishops

edit- Tobias Mullen, appointed Bishop of Erie in 1868

- James O'Connor, appointed Vicar Apostolic of Nebraska in 1876 and later Bishop of Omaha

- Ralph Leo Hayes, appointed Bishop of Helena in 1933 and later Rector of the Pontifical North American College and Bishop of Davenport

- Jerome Daniel Hannan, appointed Bishop of Scranton in 1954

- Howard Joseph Carroll, appointed Bishop of Altoona in 1957

- William G. Connare, appointed Bishop of Greensburg in 1960

- Cyril John Vogel (priest here, 1931–1951), appointed Bishop of Salina in 1965

- Norbert Felix Gaughan (priest here, 1945–1951), appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Greensburg in 1975 and later Bishop of Gary

- Nicholas C. Dattilo, appointed Bishop of Harrisburg in 1989

- Adam J. Maida, appointed Bishop of Green Bay in 1983 and later Archbishop of Detroit (elevated to Cardinal in 1994)

- Daniel DiNardo, appointed Coadjutor Bishop (in 1997) and Bishop of Sioux City and later Coadjutor Bishop, Coadjutor Archbishop, and Archbishop of Galveston-Houston (elevated to Cardinal in 2007)

- Edward J. Burns, appointed Bishop of Juneau in 2009 and later Bishop of Dallas

- Bernard A. Hebda, appointed Bishop of Gaylord in 2009 and later Coadjutor Archbishop of Newark and Archbishop of Saint Paul and Minneapolis

- David Bonnar, appointed Bishop of Youngstown in 2021

Churches

editEducation

editAs of 2018, the Diocese of Pittsburgh schools had an enrollment of approximately 17,000 students and employed nearly 1,500 teachers, making it the fourth largest school system in Pennsylvania.[38] The system operated 69 elementary, pre-K and special schools.[38] The diocese in 2018 stated that enrollment in its school system had fallen by 50 percent since 2000.[39]

Elementary schools

editBetween 2005 and 2010, the diocese closed 16 elementary schools.[40][41] In 2018, the diocese closed Saint Rosalia Academy in Greenfield. It also merged North American Martyrs School and Saint Bernadette School in Monroeville into the new Divine Mercy Academy.[39]

In 2020, the Pittsburgh-East Regional Catholic Elementary Schools (PERCES) closed East Catholic School in Forest Hills and Saint Maria Goretti in Bloomfield.[42][43] PERCES also merged Saint Anne School in Castle Shannon, Saint Bernard School in Mount Lebanon, Our Lady of Grace School in Scott Township, and Saint Thomas More School in Bethel Park into one school program. The program would have two preschool through eighth grade sites at Saint Thomas More and Saint Bernard.[44]

High schools

editDiocesan

edit- Bishop Canevin High School – Pittsburgh

- Central Catholic High School – Pittsburgh (All boys)

- North Catholic High School – Cranberry Township

- Oakland Catholic High School – Pittsburgh (All girls)

- Serra Catholic High School – McKeesport

- Seton-La Salle Catholic High School – Mt. Lebanon

Parochial

editSt. Joseph High School – Harrison Township

Private or independent

edit- Aquinas Academy – Hampton Township

- Nazareth Prep – Emsworth

- Our Lady of the Sacred Heart High School – Moon Township

Closed schools

edit- Quigley Catholic High School – Baden

- Vincentian Academy – McCandless Township

Higher education

editThree Catholic colleges and universities operate within the diocese. While affiliated with the Catholic Church, these institutions only receive indirect support from the diocese, such as tuition support for students from diocesan schools.[45]

- Duquesne University – Pittsburgh

- Carlow University – Pittsburgh

- La Roche College – McCandless

Seminarians in the diocese complete their pre-theological studies at Saint Paul Seminary in Pittsburgh.[46]

Ministries

editThe Diocese of Pittsburgh sponsors a yearly Medallion Ball. It is a debutante ball that honors young women who perform at least 100 hours of eligible volunteer work. The proceeds from the event benefit St. Lucy's Auxiliary to the Blind. In 2002, a Joan of Arc Medallion was awarded to a young woman with Down syndrome who had volunteered as a teacher's assistant. In 2013, a medallion winner was legally blind and had volunteered with a therapeutic horseback-riding program. It is common for attendees to perform more than 800 hours of volunteer work.[30]

The diocese holds a biannual "The Light is On For You" campaign to help Catholics reconnect to the church. The campaign makes it more convenient for Catholics to make confession. During the campaign, confession is available at all diocesan churches for extended hours.[47]

Sexual abuse cases

edit1978 to 1990

editIn July 1978, a woman called the Pittsburgh Police to complain that Anthony Cipolla had sexually abused her two sons, ages nine and 12. The abuse allegedly took place at a hotel room in Dearborn, Michigan and at Cipolla's rectory, with Cipolla giving the boys fake physical examinations. During the preliminary hearing, Bishop Leonard called the mother, urging her to drop the charges. Leonard said that the diocese would take case of Cipolla. The mother eventually followed his advice and the diocese transferred Cipolla to another diocese.[48]

In 1988, Tim Bendig told the diocese that Cipolla had sexually abused him from around 1981 to 1986. Like the earlier two victims, Cipolla administered physical exams to Bendig and rubbed baby powder on his body. The diocese removed Cipolla from ministry and sent him to St. Michael's Institute n New York City. When Cipolla finished there, St. Michael's gave him a positive recommendation to return to ministry. However, Bishop Wuerl refused to return him to ministry until he was evaluated at a different center; Cipolla refused the order. Wuerl suspended Cipolla from priesthood in 1990. In 1992, Bendig sued the diocese. Cipolla appealed his suspension to the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura, which in March 1993 ordered Wuerl to return him to ministry.[49] The diocese in 1993 made a financial settlement with Bendig.[48] The Vatican in 1995 reversed its 1993 ruling and permanently suspended Cipolla from public ministry. In 2002, Cipolla was laicized by the Vatican.[50][51]

In 1985, John O'Connor from the Diocese of Camden was charged with inappropriately touching a 14-year-old boy in Cape May, New Jersey, during a sleepover. O'Connor was arrested, then released to a pretrial intervention program in Toronto, followed by a period of court supervision. After O'Connor completed the program, Camden Bishop George Henry Guilfoyle asked Bishop Bevilacqua to accept O'Connor in the Diocese of Pittsburgh. Bevilacqua agreed and assigned O'Connor as a hospital chaplain. O'Connor was moved back to Camden in 1993 because his 1985 victim had sued that diocese and received a settlement.[52]

In September 1987, the diocese received an accusation of sexual abuse against three priests: Richard Zula, Francis Pucci and Robert Wolk. The three men were accused of sexually abusing two young brothers between 1984 and 1986. The two brothers filed suit against the diocese in May 1988.

- Zula was arrested in September 1988 and charged with over 130 counts of child sexual abuse against the two brothers.[53] He pleaded guilty and was sentenced in 1990 to two to five years in prison.[53]

- Pucci was never charged with any crimes due to the passage of the statute of limitations. Prosecutors accused the diocese of a lack of cooperation in the investigation. More allegations against Pucci would arise during the 1990s.[54]

- Wolk was arrested in October 1988 and charged with oral sodomy and attempted anal sex. He pleaded guilty in January 1990 and was sentenced to five to ten years in prison. He was convicted of similar offenses in another Pennsylvania county in June 1988.[55]

Wuerl met with the family of the brothers in early 1989, despite the warnings of his advisors. Wuerl said, "The lawyers could talk to one another, but I wasn't ordained to oversee a legal structure. As their bishop I was responsible for the Church's care of that family, and the only way I could do that was to go see them.[30] In March 1989, the diocese settled the brothers' lawsuit for $900,000.[53] Wuerl then implemented a "zero tolerance" policy against sexual abuse.[30]

Wuerl informed all diocesan priests that sexual contact with a minor was not merely a sin, but a crime that would result in permanent removal from the ministry and maybe prison. Priests were instructed to report any allegation of sexual abuse committed by a priest or church employee to the chancery. The diocese created the Diocesan Review Board in 1989 to offer evaluations and recommendations to the bishop on the handling of all sexual abuse cases.[30]

1990 to present

editThe Diocese of Pittsburgh removed David Dzermejko from Mary, Mother of the Church Parish in Charleroi in 2009 after the diocese received accusations from two men of sexual abuse in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[56][57] In May 2013, he was indicted on charges of possessing child pornography.[58] Police had found over 100 pornographic images on his computer. Dzermejko pleaded guilty in April 2014 and was sentenced to three years in prison.[59]

In December 2011, a woman entering the office of Bartley A. Sorensen observed him looking at child pornography on his computer. She immediately reported him to the diocese, which suspended him and notified authorities. Police found over 5,000 pornographic images on his computer along with printed materials. He pleaded guilty in May 2021 and was sentenced to 93 months in prison.[60]

Deacon Rosendo Dacal was arrested in April 2018 on charges of unlawful contact with a minor and criminal use of communications. Dacal in December 2017 started communicating in a chat room with a teenage boy, sending the boy sexually explicit messages and pornographic images. However, the boy was actually a North Strabane police officer.[61] Dacal pleaded guilty and was sentenced to two years of probation and 100 hours of community service.[62]

In August 2018, a man from Southeast Asia accused Hugh Lang, the retired pastor of Saint Therese of Lisieux Parish in Munhall, of sexual abuse. The plaintiff said that Lang of sexually assaulted him in 2001 when he was a boy during a training session for altar servers. Lang was arrested in January 2019 on assault charges.[63] Lang denied the charges. He was convicted of six sexual abuse charges and sentenced in February 2020 to nine to 23 months in jail.[64] However, a judge overturned Lang's conviction in March 2020, due to an error by the presiding judge. Prosecutors later decided to drop the charges.[65]

Pennsylvania grand jury investigation

editIn early 2016, a grand jury investigation, led by Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro, began an inquiry into sexual abuse by Catholic clergy in six Pennsylvania dioceses, including the Diocese of Pittsburgh.[66] The six dioceses in August 2018 sued the attorney general in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, opposing the release of the grand jury report. They raised issues about the rights of priests named in the report, including the lack of due process and fairness, the deprivation of the right to personal reputation and the inability of clergy to defend themselves.[67] The court allowed the state to publish the grand jury report.

In 2018, Zubik confirmed that the diocese would release the list of clergy accused of sex abuse when the grand jury report was made public.[68][69] In his letter, Zubik noted that the diocese had implemented policies to deal with sexual abuse 30 years ago. Clergy, church employees, and volunteers were all required to go through sexual abuse training programs and criminal background checks. Zubik also noted that 90% of all the allegations in the report occurred before 1990.[69]

The Pennsylvania grand jury report was released in August 2018.[70][71] It listed 99 priests who had served in the Diocese of Pittsburgh.[70] The report stated that some priests in the diocese ran a child porn ring in the 1970s and 1980s, saying they "used whips, violence and sadism in raping their victims."[72][73] These abusive priests gave their victims gold crosses so that other pedophile priests would recognize them.[73]

Sexual abuse lawsuits

editIn January 2020, a lawsuit against the Diocese of Pittsburgh which was filed by sex abuse survivors, as well as their parents, in September 2018 was allowed to move forward.[74] In February 2020, it was reported that the lawsuit did not involve requests for monetary awards, but rather greater disclosure of sex abuse records.[75] On April 15, 2020, a man filed a lawsuit against the Diocese of Pittsburgh for allegedly shielding priests who sexually abused him as a boy.[76] On August 7, 2020, a new lawsuit was filed against the Diocese of Pittsburgh from a man alleging that Leo Burchianti attacked and raped him twice when he was an altar boy.[77] Burchianti, who died in 2013, is also accused of having inappropriate sexual relationships with at least eight boys and was previously mentioned in the state grand report.[77] Wuerl and Zubik have been named as defendants in numerous lawsuits as well.[78][76][79][80]

On August 13, 2020, 25 new sex abuse lawsuits were filed against the Diocese of Pittsburgh.[81] On August 14, 2020, it was revealed that the Diocese of Pittsburgh, along with Archdiocese of Philadelphia, Diocese of Allentown and Diocese of Scranton, was enduring the bulk of 150 new lawsuits filed against all eight Pennsylvania Catholic dioceses.[82] On November 20, 2020, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court denied a petition filed by the Diocese of Pittsburgh to grant a stay which would've delayed three ongoing lawsuits against the Diocese.[83]

See also

edit- Catholic Church in the United States

- Ecclesiastical Province of Philadelphia

- Global organisation of the Catholic Church

- List of Catholic archdioceses (by country and continent)

- List of Catholic dioceses (alphabetical) (including archdioceses)

- List of Catholic dioceses (structured view) (including archdioceses)

- List of the Catholic dioceses of the United States

References

edit- ^ Hill, William (June 30, 2008). "Parish eucharistic adoration to highlight Year of St. Paul". Pittsburgh Catholic. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

St. Paul is our secondary patron with Mary, under the title of her Immaculate Conception, being our primary patroness.

- ^ "Priests". Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ The Illustrated Catholic family annual for the United States, for the year of our Lord 1884. New York: The Catholic Publication Society. 1884. pp. 90–91.

- ^ Carden, Terry (July 7, 2005). Coming of Age In Scranton: Memories of a Puer Aeternus. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-80765-9.

- ^ Weis, Frederick Lewis (1978). The Colonial Clergy of the Middle Colonies, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Genealogical Publishing Com. p. 121. ISBN 9780806307992.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopeida: Archdiocese of New York". New Advent. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2006.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia". Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Clarke, Richard Henry (1888). Lives of the Deceased Bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States. Vol. III. New York: P. O'Shea Publisher.

- ^ "Pittsburgh (Diocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Pittsburgh". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "History". Sacred Heart Province. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Former Diocesan Bishops". Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ White, E.T. (1896). The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. J.T. White. p. 336.

- ^ "Duquesne University". New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. IV. McGraw-Hill Book Company. 1967. pp. 1111–1112.

- ^ "Bishop Richard Phelan [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ^ "Canevin", Right Reverend John Francis Regis", The Catholic Encyclopedia and Its Makers, New York, the Encyclopedia Press, 1917, p. 26 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Bishop H.C. Boyle of Pittsburgh, 77; Diocesan Head 29 Years Dies—Noted Educator Had Long Aided Cause of Labor". The New York Times. December 23, 1950.

- ^ "Mission & History". www.centralcatholichs.com. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "About Carlow | Pittsburgh, Pa". Carlow University. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "John Francis Cardinal Dearden [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ Cheney, David M (November 20, 2010). "Diocese of Pittsburgh". Catholic-Hierarchy. Archived from the original on October 16, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ^ "Princely Promotions - TIME". September 30, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ TIME Magazine. How Vatican II Turned the Church Toward the World December 17, 1965

- ^ "Bishop's Latin School History". Bishop's Latin School Alumni Association. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ Handy, D. Antoinette; Williams, Mary Lou (1980). "First Lady of the Jazz Keyboard". The Black Perspective in Music. 8 (2): 195–214. doi:10.2307/1214051. ISSN 0090-7790. JSTOR 1214051.

- ^ "Mission and Ministry ~ Home | La Roche University". laroche.edu. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Bishop Leonard Dies". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. August 29, 1994.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Bishop, Ailing, Retires". Philadelphia Inquirer. July 7, 1983.

- ^ "Lavish spending in archdiocese skips inner city". natcath.org. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Rodgers, Ann; Aquilina, Mark (2015). Something More Pastoral: The Mission of Bishop, Archbishop, and Cardinal Donald Wuerl. Lambing Press.

- ^ Wereschagin, Mike (July 22, 2007). "Bishop Zubik Will Face Many Obstacles". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Kengor, Paul (May 26, 2018). "Showdown? Conor Lamb v. Bishop David Zubik". TribLIVE. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ "On Mission for the Church Alive". St. Thomas More Parish. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- ^ On Mission – Frequently Asked Questions Archived March 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine "From 2000 to 2015 Mass attendance in the Diocese of Pittsburgh decreased 40 percent while participation in the sacraments declined 40 to 50 percent. Half of all parishes now experience operational deficits, and by 2025, the number of diocesan priests available for active ministry is expected to decrease from the current 216 priests to 112." Accessed June 22, 2017.

- ^ LaRussa, Tony (October 15, 2018). "Pittsburgh diocese's new parish groupings, clergy assignments begin today". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- ^ Tom, Davidson. "Bishop Zubik announces diocesan changes". The Times Online. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ Stinelli, Mick (July 16, 2021). "Traditionalist Catholic Pittsburghers praise Latin Mass at North Side church". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, PA. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Biedka, Chuck (March 17, 2018). "Pittsburgh Diocese announces school mergers, closings". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ a b Schneider, Sarah (March 19, 2018). "Pittsburgh Diocese Announces School Mergers Citing Declining Enrollment And Financial Challenges". 90.5 WESA. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ Cronin, Mike (May 3, 2010). "Lawrenceville's St. John Neumann will be 16th closing since 2005". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Tribune-Review Publishing Company. Retrieved May 6, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Bishop: Ongoing Catholic church, school consolidation plans helping Pittsburgh diocese". WPXI. November 8, 2017. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ "Letter from Very Reverend Kris D. Stubna, S.T.D. – East Catholic School | Pittsburgh East Regional Catholic Elementary Schools". perces.org. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ "Letter from Very Reverend Kris D. Stubna, S.T.D. – St. Maria Goretti | Pittsburgh East Regional Catholic Elementary Schools". perces.org. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ "Bishop Zubik takes steps for regional sustainability of Catholic schools". Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Franko, John (December 4, 2015). "Diocese, Carlow partner to offer tuition support". The Pittsburgh Catholic. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Apone, Carl (November 19, 1967). "New Look in the Seminary". Pittsburgh Press. pp. 32–36. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Rittmeyer, Brian (March 15, 2018). "Pittsburgh Catholic churches offering confession for those away from church". TribLIVE. Archived from the original on March 18, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ a b "Reverend Anthony J. Cipolla - Pennsylvania Grand Jury Report" (PDF). Office of the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. August 14, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Gibson, Gail; Rivera, John (April 11, 2002). "Maryland center claims success treating priests". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Rodgers-Melnick, Ann (November 16, 2002). "Rare sanction imposed on priest". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Peter (September 13, 2016). "Obituary: Anthony Cipolla / Center of high-profile sex-abuse case in 1990s, dies in Ohio". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ DeRosier, John. "Ex-Vineland priest named in Pennsylvania child sex abuse report", The Press of Atlantic City, August 16, 2018

- ^ a b c "The Case of Father Richard Zula - Pennsylvania Grand Jury" (PDF). Office of the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. August 14, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Reverend Francis Pucci" (PDF). Office of the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. August 14, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Reverend Robert G. Wolk - Pennsylvania Grand Jury" (PDF). Office of the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. August 14, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Catholic Diocese finds sexual abuse allegations "credible"". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. August 11, 2010.

- ^ Rodgers, Ann (June 18, 2009). "Catholic pastor accused of child sexual abuse". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ "Former Pittsburgh Priest Charged with Child Porn Possession". 90.5 WESA. May 20, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Hayes, Harold (April 26, 2014). "Ex-priest Sentenced in Child Pornography Case". KDKA. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Reverend Bartley A. Sorensen - Pennsylvania Grand Jury Report" (PDF). Office of the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. August 14, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ Guza, Megan (April 11, 2018). "Police: Pittsburgh-area deacon sent explicit messages to cop posing as teen boy". Tribune-Review. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Lindstrom, Natasha (January 24, 2019). "Mccandless Catholic Deacon in Child Sex Sting Gets Probation, Community Service". Tribune-Review. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Guza, Megan (January 25, 2019). "Retired Munhall Catholic Priest Arrested, Charged with Child Sex Abuse". The Tribune-Review. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Retired priest, 89, convicted of abusing boy at church in 2001 sentenced". WTAE. February 6, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Davidson, Tom (March 17, 2020). "DA's office appeals tossed conviction of Pittsburgh-area priest accused of abuse". TribLive. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Couloumbis, Angela (June 17, 2018). "Pa. report to document child sexual abuse, cover-ups in six Catholic dioceses". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Castille, Ronald (August 6, 2018). "Releasing Catholic clergy abuse report risks violating constitutional rights | Opinion". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Lindstrom, Natasha (August 5, 2018). "Pittsburgh Catholic Diocese tells parishioners it will release names of priests accused of child sex abuse". TribLive. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ a b Kurutz, Daveen Rae. "Bishop Zubik Pittsburgh Diocese will name clergy accused of sex abuse". The Times. Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ a b "FULL LIST: Names from Pittsburgh and Greensburg Catholic dioceses that appear in Pennsylvania grand jury report". WTAE. August 14, 2018. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ "Grand Jury Report Into Sexual Abuse In 6 Pa. Dioceses Released". August 14, 2018. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Gambacorta, David (August 15, 2018). "Priests ran child porn ring in Pittsburgh diocese: State AG's grand jury report". Philly.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ a b "Grand jury report describes a 'ring of predatory priests' in Pittsburgh in the 1970s". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ "Judge Allows Lawsuit Alleging Pittsburgh Diocese Created 'Public Nuisance'". CBS News Pittsburgh. January 9, 2020. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Erdley, Deb (February 10, 2020). "Clergy sex abuse class action lawsuit against Pittsburgh diocese seeks to add Greensburg, others | TribLIVE.com". triblive.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Lindstrom, Natasha (April 15, 2020). "Man sues Pittsburgh diocese, alleging sexual abuse by priests decades ago | TribLIVE.com". triblive.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Cassesse, Shelby (August 7, 2020). "Lawsuit Against Catholic Diocese Of Pittsburgh Accuses Priest Of Sexual Abuse". KDKA 2. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Ward, Paula Reed (August 7, 2020). "Lawsuit against Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh accuses priest of rape". triblive.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Diocese, Zubik, Wuerl sued in latest round of accusations". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Matoney, Nick (November 20, 2019). "Former altar boys sue Pittsburgh Catholic Diocese over alleged sexual abuse". WTAE. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Cholodofsky, Rich (August 13, 2020). "Dozens of clergy sex abuse lawsuits filed in Allegheny, Westmoreland courts as possible deadline looms 2 years after report". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Mark Scolforo (August 14, 2020). "2 years after grand jury report on Pa. clergy sex abuse, lawsuits roll in". pennlive. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "State's top court says sex abuse lawsuits against dioceses can proceed". Pittsburgh Post Gazette. November 20, 2020. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

Sources

edit- Glenn, Francis A. (1993). Shepherds of the Faith 1843–1993: A Brief History of the Bishops of the Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh. ISBN none.

External links

edit- Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh Official Site

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.