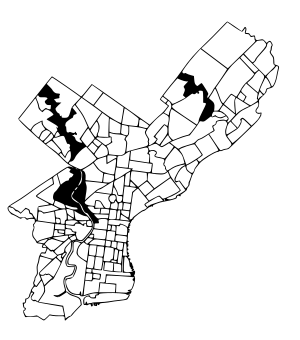

39°57′13.44″N 75°10′9.80″W / 39.9537333°N 75.1693889°W

Penn Center | |

|---|---|

Penn Center in 2006 | |

| |

| Country | |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Philadelphia County |

| City | Philadelphia |

| Area code(s) | 215, 267, and 445 |

Penn Center is the heart of Philadelphia's central business district. It takes its name from the nearly five million square foot office and retail complex it contains. It lies between 15th and 19th Streets, and between John F. Kennedy Boulevard and Market Street. It is credited with bringing Philadelphia into the era of modern office buildings.[citation needed]

History

editIn 1881, the Pennsylvania Railroad brought passenger service into the center of the city, and constructed the first Broad Street Station just west of City Hall. The sea of iron pillars holding up the PRR's elevated trackbed was replaced in the 1890s by a 10-block stone viaduct to the Schuylkill River. This created a block-wide barrier known as The Chinese Wall, cutting the western portion of the city in half and discouraging development there.

At the time, most commercial activity in Center City was east of Broad Street, which is why the SEPTA Market-Frankford Line has no stops between 30th Street Station and 15th Street. The stations at 19th Street and 22nd Street are served by SEPTA Subway-Surface Trolley Lines.

In 1925, the Pennsylvania Railroad announced its intention to leave Broad Street Station, freeing the land for redevelopment. The railroad, which had both outgrown the station and was operationally burdened by its stub-end nature, would move its operations to the newly constructed 30th Street Station and Suburban Station. Those stations were completed and in operation by 1933, but a number of factors, including the Great Depression which stalled the planned redevelopment, forced the railroad to continue utilizing Broad Street Station for certain types of trains (such as the Philadelphia-New York "Clockers", and steam-powered trains of the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines) for nearly two more decades. Broad Street Station was not completely vacated until 1952, during the term of Mayor Joseph S. Clark. Plans for the demolition of the Chinese Wall and accompanying train station were finalized and both were razed in 1953.

Ed Bacon, executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, came up with a master plan for a four-block area to be cleared. Bacon named the new site Penn Center with the hopes that it would become a business center and model for future development. His plan for the redevelopment of the site included three large office towers, a pedestrian mall, and an underground concourse where retail and business was to be located. He picked architect Vincent Kling to design most of the buildings over Louis Kahn, another possible contender.[1] The Pennsylvania Railroad wanted to sell the land off in smaller lots for piecemeal development, but Mayor Clark used his political clout to see that Bacon's plan was realized.[2] The plan was implemented with public support, but it would come into criticism later from urban planners, and notable journalist Jane Jacobs for placing vibrant urban activity underground leaving no use for the above ground promenade, and failing to account for actual human usage of the space.[3]

Throughout the mid-to-late 20th century, the city's office sector began to move west into the Penn Center area, thanks to planning efforts. As the office-working population became more suburbanized, convenient access to Suburban Station began to take precedence to city planners over local city transit access.

Today, the Penn Center name is officially attached to 11 mid- and highrise office buildings.

Most of the buildings of the complex are connected to the Suburban Station retail concourse (renovated in 2007) and by extension the Center City Concourse. The buildings share a loading and delivery entrance on Commerce Street which connects to all the buildings underground. Although not part of Penn Center, the Comcast Center connects to the concourse; such an option was also examined for the canceled American Commerce Center.

Buildings

editThe numbers of the Penn Center buildings generally radiate clockwise around One Penn Center, the oldest building.[4] John F. Kennedy Boulevard, on which many Penn Center buildings front, was known as Pennsylvania Boulevard until 1964, after the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[5]

| Name | Address | Height Feet (meters) |

Floors | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Penn Center (Suburban Station) | 1617 JFK Boulevard | 330 feet (101 m) | 20 floors | 1929 | Originally Broad Street Suburban Station; headquarters of the Pennsylvania Railroad 1930–1957, known as the Transportation Building. Office building completely renovated by Richard I. Rubin & Co. in 1983.[6][7] |

| Two Penn Center | 1500 JFK Boulevard | 271 feet (83 m) | 20 floors | 1958 | [8] |

| Three Penn Center | 1515 Market Street | 270 feet (82 m) | 20 floors | 1953 | Currently known as 1515 Market Street, this was the first of the modern Penn Center buildings.[9] |

| Four Penn Center | 1600 JFK Boulevard | 275 feet (89 m) | 20 floors | 1964 | Completely renovated in 2001.[10] |

| Five Penn Center | 1601 Market Street | 490 feet (149 m) | 36 floors | 1970 | Tallest Penn Center building before the completion of the Mellon Bank Center.[11] |

| Six Penn Center | 1701 Market Street | 248 feet (76 m) | 18 floors | 1957 | Now known as The Morgan, Lewis & Bockius Building.[12] Headquarters of the PRR 1957–1968, Penn Central 1968–1976, and Conrail 1976–1991. Completely renovated in 1999. |

| Seven Penn Center | 1635 Market Street | 269 feet (82 m) | 21 floors | 1966 | [13] |

| Eight Penn Center | 1628 JFK Boulevard | 284 feet (87 m) | 23 floors | 1982 | Site was originally an ice skating rink.[14] |

| Nine Penn Center (BNY Mellon Center) | 1735 Market Street | 792 feet (241 m) | 54 floors | 1990 | Site was originally Greyhound Bus Terminal.[15] |

| Ten Penn Center | 1801 Market Street | 306 feet (93 m) | 28 floors | 1980 | Lobby completely renovated in 2000.[16] |

| Eleven Penn Center | 1835 Market Street | 425 feet (130 m) | 29 floors | 1986 | An unusual hexagonally shaped building with mansard roof.[17] |

| Sheraton Hotel | 27 floors | 1957 | Demolished; former site of the Public Defender Building and current site of Comcast Center.[18] | ||

| Penn Center Inn | 22 floors | 1958 | Demolished in 1990 to make way for the second IBX Tower, which was never built. Site remained undeveloped until construction of a residential tower in 2016.[19] |

References

edit- ^ "On Vincent Kling, 1916–2013 - Hidden City Philadelphia". 13 January 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Lowe, Jeanne R., Cities in a Race With Time: Progress and Poverty in America's Renewing Citiesp332, Random House, NY 1967.

- ^ Johnson, Eleanor and the editors of Fortune, The Exploding Metropolis: A study of the Assault on Urbanism and How Our Cities Can Resist it p 144, Doubleday, 1957.

- ^ "Suburban Station". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Fitzpatrick, Frank (22 November 2013). "A region in mourning: The death of JFK". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Downey, Sally A. (12 June 2006). "Bernard M. Guth, 71, lawyer, music patron". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Gelb, Matt (29 December 2015). "Artist Ellsworth Kelly's Philadelphia legacy". www.inquirer.com. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Two Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Three Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Four Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Five Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Six Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Seven Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Eight Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Nine Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Ten Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2006. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Eleven Penn Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Sheraton Penn Center Hotel". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Penn Center Inn". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

Geographic location

editExternal links

edit- 'Developmentally Disabled' a Philadelphia Weekly article that discusses the history of planning in Philadelphia and specifically addresses Penn Center

- 'The History of LOVE Park' a history of LOVE park that discusses Penn Center

- 'Urban Renewal in Philadelphia' a history of the development of Penn Center containing many historical photographs