The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all parts of the bodies of bilaterally symmetric and triploblastic animals—that is, all multicellular animals except sponges and diploblasts. It is a structure composed of nervous tissue positioned along the rostral (nose end) to caudal (tail end) axis of the body and may have an enlarged section at the rostral end which is a brain. Only arthropods, cephalopods and vertebrates have a true brain, though precursor structures exist in onychophorans, gastropods and lancelets.

| Central nervous system | |

|---|---|

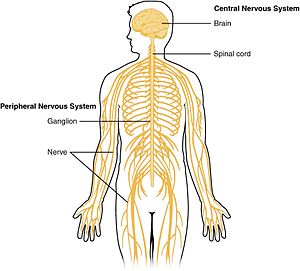

Schematic diagram showing the central nervous system in yellow, peripheral in orange | |

| Details | |

| Lymph | 224 |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | systema nervosum centrale pars centralis systematis nervosi[1] |

| Acronym(s) | CNS |

| MeSH | D002490 |

| TA98 | A14.1.00.001 |

| TA2 | 5364 |

| FMA | 55675 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The rest of this article exclusively discusses the vertebrate central nervous system, which is radically distinct from all other animals.

Overview

editIn vertebrates, the brain and spinal cord are both enclosed in the meninges.[2] The meninges provide a barrier to chemicals dissolved in the blood, protecting the brain from most neurotoxins commonly found in food. Within the meninges the brain and spinal cord are bathed in cerebral spinal fluid which replaces the body fluid found outside the cells of all bilateral animals.

In vertebrates, the CNS is contained within the dorsal body cavity, while the brain is housed in the cranial cavity within the skull. The spinal cord is housed in the spinal canal within the vertebrae.[2] Within the CNS, the interneuronal space is filled with a large amount of supporting non-nervous cells called neuroglia or glia from the Greek for "glue".[3]

In vertebrates, the CNS also includes the retina[4] and the optic nerve (cranial nerve II),[5][6] as well as the olfactory nerves and olfactory epithelium.[7] As parts of the CNS, they connect directly to brain neurons without intermediate ganglia. The olfactory epithelium is the only central nervous tissue outside the meninges in direct contact with the environment, which opens up a pathway for therapeutic agents which cannot otherwise cross the meninges barrier.[7]

Structure

editThe CNS consists of two major structures: the brain and spinal cord. The brain is encased in the skull, and protected by the cranium.[8] The spinal cord is continuous with the brain and lies caudally to the brain.[9] It is protected by the vertebrae.[8] The spinal cord reaches from the base of the skull, and continues through[8] or starting below[10] the foramen magnum,[8] and terminates roughly level with the first or second lumbar vertebra,[9][10] occupying the upper sections of the vertebral canal.[6]

White and gray matter

editMicroscopically, there are differences between the neurons and tissue of the CNS and the peripheral nervous system (PNS).[11] The CNS is composed of white and gray matter.[9] This can also be seen macroscopically on brain tissue. The white matter consists of axons and oligodendrocytes, while the gray matter consists of neurons and unmyelinated fibers. Both tissues include a number of glial cells (although the white matter contains more), which are often referred to as supporting cells of the CNS. Different forms of glial cells have different functions, some acting almost as scaffolding for neuroblasts to climb during neurogenesis such as bergmann glia, while others such as microglia are a specialized form of macrophage, involved in the immune system of the brain as well as the clearance of various metabolites from the brain tissue.[6] Astrocytes may be involved with both clearance of metabolites as well as transport of fuel and various beneficial substances to neurons from the capillaries of the brain. Upon CNS injury astrocytes will proliferate, causing gliosis, a form of neuronal scar tissue, lacking in functional neurons.[6]

The brain (cerebrum as well as midbrain and hindbrain) consists of a cortex, composed of neuron-bodies constituting gray matter, while internally there is more white matter that form tracts and commissures. Apart from cortical gray matter there is also subcortical gray matter making up a large number of different nuclei.[9]

Spinal cord

editFrom and to the spinal cord are projections of the peripheral nervous system in the form of spinal nerves (sometimes segmental nerves[8]). The nerves connect the spinal cord to skin, joints, muscles etc. and allow for the transmission of efferent motor as well as afferent sensory signals and stimuli.[9] This allows for voluntary and involuntary motions of muscles, as well as the perception of senses. All in all 31 spinal nerves project from the brain stem,[9] some forming plexa as they branch out, such as the brachial plexa, sacral plexa etc.[8] Each spinal nerve will carry both sensory and motor signals, but the nerves synapse at different regions of the spinal cord, either from the periphery to sensory relay neurons that relay the information to the CNS or from the CNS to motor neurons, which relay the information out.[9]

The spinal cord relays information up to the brain through spinal tracts through the final common pathway[9] to the thalamus and ultimately to the cortex.

-

Schematic image showing the locations of a few tracts of the spinal cord.

-

Reflexes may also occur without engaging more than one neuron of the CNS as in the below example of a short reflex.

Cranial nerves

editApart from the spinal cord, there are also peripheral nerves of the PNS that synapse through intermediaries or ganglia directly on the CNS. These 12 nerves exist in the head and neck region and are called cranial nerves. Cranial nerves bring information to the CNS to and from the face, as well as to certain muscles (such as the trapezius muscle, which is innervated by accessory nerves[8] as well as certain cervical spinal nerves).[8]

Two pairs of cranial nerves; the olfactory nerves and the optic nerves[4] are often considered structures of the CNS. This is because they do not synapse first on peripheral ganglia, but directly on CNS neurons. The olfactory epithelium is significant in that it consists of CNS tissue expressed in direct contact to the environment, allowing for administration of certain pharmaceuticals and drugs. [7]

Brain

editAt the anterior end of the spinal cord lies the brain.[9] The brain makes up the largest portion of the CNS. It is often the main structure referred to when speaking of the nervous system in general. The brain is the major functional unit of the CNS. While the spinal cord has certain processing ability such as that of spinal locomotion and can process reflexes, the brain is the major processing unit of the nervous system.[12][13]

Brainstem

editThe brainstem consists of the medulla, the pons and the midbrain. The medulla can be referred to as an extension of the spinal cord, which both have similar organization and functional properties.[9] The tracts passing from the spinal cord to the brain pass through here.[9]

Regulatory functions of the medulla nuclei include control of blood pressure and breathing. Other nuclei are involved in balance, taste, hearing, and control of muscles of the face and neck.[9]

The next structure rostral to the medulla is the pons, which lies on the ventral anterior side of the brainstem. Nuclei in the pons include pontine nuclei which work with the cerebellum and transmit information between the cerebellum and the cerebral cortex.[9] In the dorsal posterior pons lie nuclei that are involved in the functions of breathing, sleep, and taste.[9]

The midbrain, or mesencephalon, is situated above and rostral to the pons. It includes nuclei linking distinct parts of the motor system, including the cerebellum, the basal ganglia and both cerebral hemispheres, among others. Additionally, parts of the visual and auditory systems are located in the midbrain, including control of automatic eye movements.[9]

The brainstem at large provides entry and exit to the brain for a number of pathways for motor and autonomic control of the face and neck through cranial nerves,[9] Autonomic control of the organs is mediated by the tenth cranial nerve.[6] A large portion of the brainstem is involved in such autonomic control of the body. Such functions may engage the heart, blood vessels, and pupils, among others.[9]

The brainstem also holds the reticular formation, a group of nuclei involved in both arousal and alertness.[9]

Cerebellum

editThe cerebellum lies behind the pons. The cerebellum is composed of several dividing fissures and lobes. Its function includes the control of posture and the coordination of movements of parts of the body, including the eyes and head, as well as the limbs. Further, it is involved in motion that has been learned and perfected through practice, and it will adapt to new learned movements.[9] Despite its previous classification as a motor structure, the cerebellum also displays connections to areas of the cerebral cortex involved in language and cognition. These connections have been shown by the use of medical imaging techniques, such as functional MRI and Positron emission tomography.[9]

The body of the cerebellum holds more neurons than any other structure of the brain, including that of the larger cerebrum, but is also more extensively understood than other structures of the brain, as it includes fewer types of different neurons.[9] It handles and processes sensory stimuli, motor information, as well as balance information from the vestibular organ.[9]

Diencephalon

editThe two structures of the diencephalon worth noting are the thalamus and the hypothalamus. The thalamus acts as a linkage between incoming pathways from the peripheral nervous system as well as the optical nerve (though it does not receive input from the olfactory nerve) to the cerebral hemispheres. Previously it was considered only a "relay station", but it is engaged in the sorting of information that will reach cerebral hemispheres (neocortex).[9]

Apart from its function of sorting information from the periphery, the thalamus also connects the cerebellum and basal ganglia with the cerebrum. In common with the aforementioned reticular system the thalamus is involved in wakefulness and consciousness, such as though the SCN.[9]

The hypothalamus engages in functions of a number of primitive emotions or feelings such as hunger, thirst and maternal bonding. This is regulated partly through control of secretion of hormones from the pituitary gland. Additionally the hypothalamus plays a role in motivation and many other behaviors of the individual.[9]

Cerebrum

editThe cerebrum of cerebral hemispheres make up the largest visual portion of the human brain. Various structures combine to form the cerebral hemispheres, among others: the cortex, basal ganglia, amygdala and hippocampus. The hemispheres together control a large portion of the functions of the human brain such as emotion, memory, perception and motor functions. Apart from this the cerebral hemispheres stand for the cognitive capabilities of the brain.[9]

Connecting each of the hemispheres is the corpus callosum as well as several additional commissures.[9] One of the most important parts of the cerebral hemispheres is the cortex, made up of gray matter covering the surface of the brain. Functionally, the cerebral cortex is involved in planning and carrying out of everyday tasks.[9]

The hippocampus is involved in storage of memories, the amygdala plays a role in perception and communication of emotion, while the basal ganglia play a major role in the coordination of voluntary movement.[9]

Difference from the peripheral nervous system

editThe PNS consists of neurons, axons, and Schwann cells. Oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells have similar functions in the CNS and PNS, respectively. Both act to add myelin sheaths to the axons, which acts as a form of insulation allowing for better and faster proliferation of electrical signals along the nerves. Axons in the CNS are often very short, barely a few millimeters, and do not need the same degree of isolation as peripheral nerves. Some peripheral nerves can be over 1 meter in length, such as the nerves to the big toe. To ensure signals move at sufficient speed, myelination is needed.

The way in which the Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes myelinate nerves differ. A Schwann cell usually myelinates a single axon, completely surrounding it. Sometimes, they may myelinate many axons, especially when in areas of short axons.[8] Oligodendrocytes usually myelinate several axons. They do this by sending out thin projections of their cell membrane, which envelop and enclose the axon.

Development

editDuring early development of the vertebrate embryo, a longitudinal groove on the neural plate gradually deepens and the ridges on either side of the groove (the neural folds) become elevated, and ultimately meet, transforming the groove into a closed tube called the neural tube.[14] The formation of the neural tube is called neurulation. At this stage, the walls of the neural tube contain proliferating neural stem cells in a region called the ventricular zone. The neural stem cells, principally radial glial cells, multiply and generate neurons through the process of neurogenesis, forming the rudiment of the CNS.[15]

The neural tube gives rise to both brain and spinal cord. The anterior (or 'rostral') portion of the neural tube initially differentiates into three brain vesicles (pockets): the prosencephalon at the front, the mesencephalon, and, between the mesencephalon and the spinal cord, the rhombencephalon. (By six weeks in the human embryo) the prosencephalon then divides further into the telencephalon and diencephalon; and the rhombencephalon divides into the metencephalon and myelencephalon. The spinal cord is derived from the posterior or 'caudal' portion of the neural tube.

As a vertebrate grows, these vesicles differentiate further still. The telencephalon differentiates into, among other things, the striatum, the hippocampus and the neocortex, and its cavity becomes the first and second ventricles (lateral ventricles). Diencephalon elaborations include the subthalamus, hypothalamus, thalamus and epithalamus, and its cavity forms the third ventricle. The tectum, pretectum, cerebral peduncle and other structures develop out of the mesencephalon, and its cavity grows into the mesencephalic duct (cerebral aqueduct). The metencephalon becomes, among other things, the pons and the cerebellum, the myelencephalon forms the medulla oblongata, and their cavities develop into the fourth ventricle.[9]

-

Development of the neural tube

Evolution

editPlanaria

editPlanarians, members of the phylum Platyhelminthes (flatworms), have the simplest, clearly defined delineation of a nervous system into a CNS and a PNS.[16][17] Their primitive brains, consisting of two fused anterior ganglia, and longitudinal nerve cords form the CNS. Like vertebrates, have a distinct CNS and PNS. The nerves projecting laterally from the CNS form their PNS.

A molecular study found that more than 95% of the 116 genes involved in the nervous system of planarians, which includes genes related to the CNS, also exist in humans.[18]

Arthropoda

editIn arthropods, the ventral nerve cord, the subesophageal ganglia and the supraesophageal ganglia are usually seen as making up the CNS. Arthropoda, unlike vertebrates, have inhibitory motor neurons due to their small size.[19]

Chordata

editThe CNS of chordates differs from that of other animals in being placed dorsally in the body, above the gut and notochord/spine.[20] The basic pattern of the CNS is highly conserved throughout the different species of vertebrates and during evolution. The major trend that can be observed is towards a progressive telencephalisation: the telencephalon of reptiles is only an appendix to the large olfactory bulb, while in mammals it makes up most of the volume of the CNS. In the human brain, the telencephalon covers most of the diencephalon and the entire mesencephalon. Indeed, the allometric study of brain size among different species shows a striking continuity from rats to whales, and allows us to complete the knowledge about the evolution of the CNS obtained through cranial endocasts.

Mammals

editMammals – which appear in the fossil record after the first fishes, amphibians, and reptiles – are the only vertebrates to possess the evolutionarily recent, outermost part of the cerebral cortex (main part of the telencephalon excluding olfactory bulb) known as the neocortex.[21] This part of the brain is, in mammals, involved in higher thinking and further processing of all senses in the sensory cortices (processing for smell was previously only done by its bulb while those for non-smell senses were only done by the tectum).[22] The neocortex of monotremes (the duck-billed platypus and several species of spiny anteaters) and of marsupials (such as kangaroos, koalas, opossums, wombats, and Tasmanian devils) lack the convolutions – gyri and sulci – found in the neocortex of most placental mammals (eutherians).[23] Within placental mammals, the size and complexity of the neocortex increased over time. The area of the neocortex of mice is only about 1/100 that of monkeys, and that of monkeys is only about 1/10 that of humans.[21] In addition, rats lack convolutions in their neocortex (possibly also because rats are small mammals), whereas cats have a moderate degree of convolutions, and humans have quite extensive convolutions.[21] Extreme convolution of the neocortex is found in dolphins, possibly related to their complex echolocation.

Clinical significance

editDiseases

editThere are many CNS diseases and conditions, including infections such as encephalitis and poliomyelitis, early-onset neurological disorders including ADHD and autism, seizure disorders such as epilepsy, headache disorders such as migraine, late-onset neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and essential tremor, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, genetic disorders such as Krabbe's disease and Huntington's disease, as well as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and adrenoleukodystrophy. Lastly, cancers of the central nervous system can cause severe illness and, when malignant, can have very high mortality rates. Symptoms depend on the size, growth rate, location and malignancy of tumors and can include alterations in motor control, hearing loss, headaches and changes in cognitive ability and autonomic functioning.

Specialty professional organizations recommend that neurological imaging of the brain be done only to answer a specific clinical question and not as routine screening.[24]

References

edit- ^ Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary, Farlex 2012.

- ^ a b Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, US: Prentice Hall. pp. 132–144. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ^ Kettenmann, H.; Faissner, A.; Trotter, J. (1996). "Neuron-Glia Interactions in Homeostasis and Degeneration". Comprehensive Human Physiology. pp. 533–543. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-60946-6_27. ISBN 978-3-642-64619-5.

- ^ a b Purves, Dale (2000). Neuroscience, Second Edition. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 9780878937424. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014.

- ^ "Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Optic Nerve". National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Estomih Mtui, M.J. Turlough FitzGerald, Gregory Gruener (2012). Clinical neuroanatomy and neuroscience (6th ed.). Edinburgh: Saunders. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7020-3738-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Gizurarson S (2012). "Anatomical and histologica\ ]=\ factors affecting intranasal drug and vaccine delivery". Current Drug Delivery. 9 (6): 566–582. doi:10.2174/156720112803529828. PMC 3480721. PMID 22788696.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dalley, Arthur F.; Moore, Keith L; Agur, Anne M.R. (2010). Clinically oriented anatomy (6th ed., [International ed.]. ed.). Philadelphia [etc.]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer. pp. 48–55, 464, 700, 822, 824, 1075. ISBN 978-1-60547-652-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Kandel ER, Schwartz JH (2012). Principles of neural science (5. ed.). Appleton & Lange: McGraw Hill. pp. 338–343. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ a b Huijzen, R. Nieuwenhuys, J. Voogd, C. van (2007). The human central nervous system (4th ed.). Berlin: Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-3-540-34686-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller AD, Zachary JF (10 May 2020). "Nervous System". Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. pp. 805–907.e1. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-35775-3.00014-X. ISBN 9780323357753. PMC 7158194.

- ^ Thau L, Reddy V, Singh P (January 2020). "Anatomy, Central Nervous System". StatPearls. PMID 31194336. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The brain and spinal cord – Canadian Cancer Society". www.cancer.ca. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F.; College, Swarthmore; Helsinki, the University of (2014). Developmental biology (Tenth ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. ISBN 978-0878939787.

- ^ Rakic, P (October 2009). "Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 10 (10): 724–35. doi:10.1038/nrn2719. PMC 2913577. PMID 19763105.

- ^ Hickman, Cleveland P. Jr.; Larry S. Roberts; Susan L. Keen; Allan Larson; Helen L'Anson; David J. Eisenhour (2008). Integrated Princinples of Zoology: Fourteenth Edition. New York, NY, US: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 733. ISBN 978-0-07-297004-3.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Jane B. Reece; Lisa A. Urry; Michael L. Cain; Steven A. Wasserman; Peter V. Minorsky; Robert B. Jackson (2008). Biology: Eighth Edition. San Francisco, CA, US: Pearson / Benjamin Cummings. p. 1065. ISBN 978-0-8053-6844-4.

- ^ Mineta K, Nakazawa M, Cebria F, Ikeo K, Agata K, Gojobori T (2003). "Origin and evolutionary process of the CNS elucidated by comparative genomics analysis of planarian ESTs". PNAS. 100 (13): 7666–7671. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7666M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1332513100. PMC 164645. PMID 12802012.

- ^ Wolf, Harald (2 February 2014). "Inhibitory motoneurons in arthropod motor control: organisation, function, evolution". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 200 (8). Springer: 693–710. doi:10.1007/s00359-014-0922-2. ISSN 1432-1351. PMC 4108845. PMID 24965579.

- ^ Romer, A.S. (1949): The Vertebrate Body. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia. (2nd ed. 1955; 3rd ed. 1962; 4th ed. 1970)

- ^ a b c Bear, Mark F.; Barry W. Connors; Michael A. Paradiso (2007). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain: Third Edition. Philadelphia, PA, US: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 196–199. ISBN 978-0-7817-6003-4.

- ^ Feinberg, T. E., & Mallatt, J. (2013). The evolutionary and genetic origins of consciousness in the Cambrian Period over 500 million years ago. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 667. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00667

- ^ Kent, George C.; Robert K. Carr (2001). Comparative Anatomy of the Vertebrates: Ninth Edition. New York, NY, US: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 409. ISBN 0-07-303869-5.

- ^ American College of Radiology; American Society of Neuroradiology (2010). "ACR-ASNR practice guideline for the performance of computed tomography (CT) of the brain". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Reston, VA, US: American College of Radiology. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

External links

edit- Overview of the Central Nervous System at the Wayback Machine (archived 2012-02-18)

- High-Resolution Cytoarchitectural Primate Brain Atlases

- Explaining the human nervous system.

- The Department of Neuroscience at Wikiversity

- Central nervous system histology