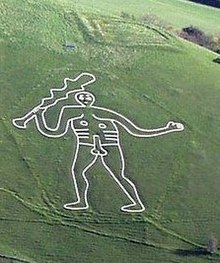

The Cerne Abbas Giant is a hill figure near the village of Cerne Abbas, in Dorset, England. It is currently owned by the National Trust, and listed as a scheduled monument of England. Measuring 55 metres (180 ft) in length, the hill figure depicts a bald, nude male with a prominent erection, holding his left hand out to the side and wielding a large club in his right hand. Like many other hill figures, the Cerne Giant is formed by shallow trenches cut into the turf and backfilled with chalk rubble.

Cerne Abbas Giant chalk figure below the rectangular "Trendle" earthworks | |

| Alternative name | Cerne Giant |

|---|---|

| Location | Giant Hill, Cerne Abbas, Dorset, England |

| Coordinates | 50°48′49″N 2°28′29″W / 50.813676°N 2.474700°W |

| Type | Hill figure monument |

| Length | 55m (180ft) |

| History | |

| Material | Chalk |

| Founded | First recorded 1694 |

| Associated with | |

| Site notes | |

| Ownership | National Trust |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | nationaltrust |

| Official name | Hill figure called The Giant |

| Designated | 15 Oct 1924 |

| Reference no. | 1003202 |

The origin and age of the figure are unclear, and archaeological evidence suggests that parts of it have been lost, altered, or added, over time; the earliest written record dates to the late 17th century. Early antiquarians associated it, albeit on little evidence, with a Saxon deity, while other scholars sought to identify it with a Romano-British figure of Hercules (or some syncretisation of the two).[1] The lack of earlier descriptions,[2] along with information given to the 18th-century antiquarian John Hutchins, has led some scholars to conclude it dates from the 17th century. Conversely, recent optically stimulated luminescence testing has suggested an origin between the years 700 CE and 1110 CE, possibly close to the 10th-century date of the founding of nearby Cerne Abbey.[3]

Regardless of its age, the Cerne Abbas Giant has become an important part of local culture and folklore, which often associates it with fertility. It is one of England's best-known hill figures and is a visitor attraction in the region.

The Cerne Giant is one of two major extant human hill figures in England, the other being the Long Man of Wilmington, near Wilmington, East Sussex, which is also a scheduled monument.

Description

editThe Giant is located just outside the small village of Cerne Abbas in Dorset, about 48 kilometres (30 mi) west of Bournemouth and 26 kilometres (16 mi) north of Weymouth. The figure depicts a naked man and is of colossal dimensions, being about 55 metres (180 ft) long and 51 metres (167 ft) across. It is cut into the steep, west-facing side of a hill known as Giant Hill[5] or Trendle Hill.[6][7] Atop the hill is another landmark, the Iron Age earthwork known as the "Trendle" or "Frying Pan".[8] The figure's outline is formed by trenches cut into the turf, about 0.6 metres (2 ft 0 in) deep, and filled-in with crushed chalk.[5] In his right hand, the giant holds a knotted club or baton-style weapon measuring 37 metres (121 ft) in length,[9] adding 11 metres (36 ft) to the total length of the figure.[10] A line across the waist has been suggested to represent a belt.[11] Writing in 1901 in the Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, Henry Colley March noted that: "The Cerne Giant presents five characteristics: (1) It is petrographic ... It is, therefore, a rock carving ... (2) It is colossal ... (3) It is nude. ... (4) It is ithyphallic ... (5) The Giant is clavigerous. It bears a weapon in its right hand."[12]

A 1996 study found that some features have changed over time, concluding that the figure originally held a cloak over its extended left arm, and an object (possibly a severed head) beneath its left hand.[13] The former presence of a cloak was corroborated in 2008, when a team of archaeologists (using special equipment) determined that part of the figure had been lost; the cloak might have been a depiction of an animal skin.[14] In 1993 the National Trust gave the Giant a "nose job" after years of erosion had worn it away.[15][16]

The Giant sports a notably vertical erection, some 11 metres (36 feet) long (nearly the length of its head), along with a visible scrotum and testicles ;[17] it has been called "Britain's most famous phallus".[18] One commentator noted that postcards of the Giant were the only indecent photographs that could be sent through the English Post Office.[19] However, this feature may also have been changed over time; based on a review of historical depictions, the Giant's current large erection has been identified as the result of the merging of a circle (representing his navel) with a different, smaller penis during a 1908 re-cut, as the navel still appeared on a late-1890s picture postcard.[20] Lidar scans, conducted as part of the 2020 survey programme, have concluded that the phallus was added much later than the bulk of the figure, which was (probably) originally clothed.[21]

The hill figure is most commonly known as the "Cerne Abbas Giant"[22][23][24][25] or the "Cerne Giant",[22][26] the latter being preferred by the National Trust; English Heritage and Dorset County Council call it simply "the Giant".[5][27] It has also been referred to as the "Old Man",[28] and occasionally, in recent years, as the "Rude Man" of Cerne.[29][30]

Although the best view of the Giant is from the air, most tourist guides recommend a ground view from the "Giant's View" lay-by and car park off the A352.[31][32] The surrounding area was developed in 1979 through a joint effort of the Dorset County Planning Department, the National Trust, the Nature Conservancy Council (now called Natural England), the Dorset Naturalists Trusts, the Department of the Environment, and local landowners. The information panel on-site was devised by the National Trust and Dorset County Council.[33]

History

editEarly accounts

editLike several other chalk figures carved into the English countryside, the Cerne Abbas Giant is often thought of as an ancient creation but its written history cannot be traced back further than the late 17th century. Medieval sources refer to the hill on which the giant is located as Trendle Hill, in reference to the nearby Iron Age earthwork known as the Trendle.[6][8] J. H. Bettey of the University of Bristol noted that none of the earlier sources for the area, including a detailed 1540s survey of the Cerne Abbey lands and a 1617 land survey by John Norden, refer to the giant, despite noting the Trendle and other landmarks.[34] In contrast, there are documentary references to the 3,000 year-old Uffington White Horse as far back as the late 11th century.[35]

The earliest known written reference is a 4 November 1694 entry in the Churchwardens' Accounts from St Mary's Church in Cerne Abbas, which reads "for repairing ye Giant, three shillings".[36][37] In 1734, the Bishop of Bristol noted and inquired about the giant during a Canonical visitation to Cerne Abbas, while in 1738 the antiquarian Francis Wise mentioned the giant in a letter.[38] The bishop's account, as well as subsequent observations such as those of William Stukeley, were discussed at meetings of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1764.[39][40]

Beginning in 1763 descriptions of the giant also began to appear in contemporary magazines, following a general increase in interest in "antiquities". The earliest known survey was published in the Royal Magazine in September 1763. Derivative versions subsequently appeared in the October 1763 St James Chronicle, the July 1764 Gentleman's Magazine[39][41] and the 1764 edition of The Annual Register.[39][42][43][44][45] In the early 1770s the antiquarian John Hutchins reviewed various previous accounts in his book The History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset, published posthumously in 1774.[39] Noting a local tradition the giant had only been cut in the previous century, he described and drew it as then having three roughly-cut letters between its feet, and over them the apparent Arabic numerals "748", features since lost; Hutchins' account was copied by several early 19th century guidebooks.[46][47]

A map referred to as the "1768 Survey Map of Cerne Abbas by Benjamin Pryce" is held at the Dorset History Centre,[48] though a record at the National Archives notes there is evidence the map may date to the 1790s.[49] By the following century the phallus was invariably omitted from depictions, either in line with the prevailing views on modesty at the time or as it had become grassed over; the figure seems to have become increasingly neglected and overgrown during the 19th century until in 1868 its owner Lord Rivers arranged to have the Giant restored "as near as possible to his original condition".[50]

- Cerne Abbas Giant at different dates

-

1764, first known drawing from the Gentleman's Magazine with measurements, including the height of 180 feet (55 m)[41]

-

1764 sketch, perhaps dated to 1763, sent to the Society of Antiquaries of London[51]

-

1842 drawing by the antiquary and editor John Sydenham[52]

-

1892 drawing by the author and antiquarian William Plenderleath[53]

Interpretation

edit18th century antiquarians were able to discover little about the figure's origin: Stukeley suggested that local people "know nothing more of [the Giant] than a traditionary account of its being a deity of the ancient Britons".[54] Several other local traditions have, however, been recorded, including that the Giant was cut in 1539 at the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries as a "humiliating caricature" of Cerne Abbey's final abbot Thomas Corton, who amongst other offences was accused of fathering children with a mistress.[55][56] Hutchins, noting the apparent figure "748" then visible between the Giant's feet, suggested that if this did not refer to the date of an earlier repair such as "1748", it could be a representation of Cenric, the son of Cuthred, King of Wessex, who died in battle in 748: Arabic numerals however did not come widely into use in England until the 15th century.[57] Another 18th century writer dismissed it as "the amusement of idle people, and cut with little meaning, perhaps, as shepherds' boys strip off the turf on the Wiltshire plains."[58]

Richard Pococke, in a 1754 account, noted the figure was called "the Giant, and Hele",[59] while Richard Gough, editor of the 1789 edition of William Camden's 1637 work Britannica, linked the Giant with a supposed minor Saxon deity named by Camden as "Hegle";[60][61] In the 1760s William Stukeley recorded that locals referred to the giant as "Helis".[60] Stukeley was one of the first to hypothesize that "Helis" was a garbled form of "Hercules", a suggestion that has found more support;[60][62] Pococke had earlier noted that "[the Giant] seems to be Hercules, or Strength and Fidelity".[59] The close resemblance of the giant's features to the attributes of the classical hero Hercules, usually portrayed naked and with a knotted club, have been strengthened by the more recent discovery of the "cloak", as Hercules was often depicted with the skin of the Nemean lion over his arm.[60]

Modern histories of the Cerne Giant have been published by Bettey (1981), Legg (1990), and Darvill et al. (1999).[63] In recent times there have been three main theories concerning the age of the Giant, and whom it might represent:[64]

- One, citing the lack of documentary evidence prior to the 1690s, argues that the giant was created in the 17th century, most likely by Lord Holles, who held the Cerne Abbas estate by right of his second wife Jane. J.H. Bettey was the first to suggest Holles could have cut the figure as a parody of Oliver Cromwell,[65] though a further tradition local to Cerne was that the Giant was created by Holles' tenants as a lampoon aimed at Holles himself.[66]

- Another, based largely on an idea developed in the 1930s by archaeologist Stuart Piggott, is that due to the giant's resemblance to Hercules, it is a creation of the Romano-British culture, either as a direct depiction of the Roman figure or of a deity identified with him.[13] It has been more specifically linked to attempts to revive the cult of Hercules during the reign of the Emperor Commodus (176-192), who presented himself as a reincarnation of Hercules.[67]

- Another is that the giant is of earlier Celtic origin, because it is stylistically similar to an image of the Celtic god Nodens on a skillet handle found at Hod Hill, Dorset, dated to between 10 CE to 51 CE.[64]

Proponents of a 17th-century origin suggest that the giant was cut around the time of the English Civil War by servants of Denzil Holles, then Lord of the Manor of Cerne Abbas. This theory originated in the 18th century account of John Hutchins, who noted in a letter of 1751 to the Dean of Exeter that the steward of the manor had told him the figure "was a modern thing, cut out in Lord Hollis' time".[8] In his History and antiquities of the county of Dorset, first published in 1774, Hutchins also suggested that Holles could perhaps have ordered the recutting of an existing figure dating from "beyond the memory of man".[61][68]

It has been speculated that Holles could have intended the figure as a parody of Oliver Cromwell: while Holles, the MP for Dorchester and a leader of the Presbyterian faction in Parliament, had been a key Parliamentarian supporter during the First English Civil War, he grew to personally despise Cromwell and attempted to have him impeached in 1644.[69] Cromwell was sometimes mockingly referred to as "England's Hercules" by his enemies: under this interpretation, the club has been suggested to hint at Cromwell's military rule, and the phallus to mock his Puritanism.[70] In 1967 Kenneth Carrdus proposed that the Holles referred to in Hutchins' account was Denzil Holles' son Francis, MP for Dorchester in 1679-80: he claimed that the figures and letters noted by Hutchins could be made to read "fh 1680", though was unable to find much other evidence to support this.[71]

The deepest archeological horizon of the Giant is 1 metre. Results of optically stimulated luminescence testing of samples from this deepest level were published in 2021. Some of these samples support a construction date between 700 CE and 1110 CE, suggesting the Giant was first cut in the late Anglo-Saxon period. As this date coincides with the founding of nearby Cerne Abbey, archaeologist Alison Sheridan speculated that it may have been a challenge to the new religion from the still-pagan local inhabitants,[72][73] although other scholars have noted that early medieval monks could equally have been responsible for the figure.[74]

Other samples, however, gave later dates ranging up to 1560; one possible explanation is that the Giant may have first been cut in the late Saxon period, but then abandoned for several centuries.[72] As the survey evidence also suggested that the giant's penis is of much later date than the rest of the figure, the National Trust has proposed that the feature could have been added by Holles as part of his parody of Cromwell when re-cutting the older figure.[21]

Modern history

editIn 1920, the giant and the 4,000 square metres (0.99 acres) site where it stands were donated to the National Trust by its then land-owners, Alexander and George Pitt-Rivers,[75] and it is now listed as a Scheduled Monument.[5] During World War II the giant was camouflaged with brushwood by the Home Guard in order to prevent its use as a landmark for enemy aircraft.[76][77]

According to the National Trust, the grass is trimmed regularly and the giant is fully re-chalked every 25 years.[78] Traditionally, the National Trust has relied on sheep from surrounding farms to graze the site.[79] However, in 2008 a lack of sheep, coupled with a wet spring causing extra plant growth, forced a re-chalking of the giant,[80] with 17 tonnes of new chalk being poured in and tamped down by hand.[81] In 2006, the National Trust carried out the first wildlife survey of the Cerne Abbas Giant, identifying wild flowers including the green-winged orchid, clustered bellflower and autumn gentian, which are uncommon in England.[82]

In 1921 Walter Long of Gillingham, Dorset, objected to the giant's nudity and conducted a campaign to either convert it to a simple nude, or to cover its supposed obscenity with a leaf.[83] Long's protest gained some support, including that of two bishops,[18][19] and eventually reached the Home Office. The Home Office considered the protest to be in humour, though the chief constable responded to say the office could not act against a protected scheduled monument.

Archaeology

editA 1617 land survey of Cerne Abbas makes no mention of the giant, suggesting that it may not have been there at the time or was perhaps overgrown.[34] The first published survey appeared in the September 1763 issue of Royal Magazine, reprinted in the October 1763 issue of St James Chronicle, and also in the August 1764 edition of Gentleman's Magazine together with the first drawing that included measurements.[39]

Egyptologist and archaeology pioneer Sir Flinders Petrie[84] surveyed the giant, probably during the First World War, and published his results in a Royal Anthropological Institute paper in 1926.[75][85] Petrie says he made 220 measurements, and records slight grooves across the neck, and from the shoulders down to the armpits. He also notes a row of pits suggesting the place of the spine. He concludes that the giant is very different from the Long Man of Wilmington, and that minor grooves may have been added from having been repeatedly cleaned.[85]

In 1764, William Stukeley was one of the first people to suggest that the giant resembled Hercules.[40] In 1938, British archaeologist Stuart Piggott agreed, and suggested that, like Hercules, the giant should also be carrying a lion-skin.[86][87] In 1979, a resistivity survey was carried out, and together with drill samples, confirmed the presence of the lion-skin.[88] Another resistivity survey in 1995 also found evidence of a cloak and changes to the length of the phallus, but did not find evidence (as rumoured) of a severed head, horns, or symbols between the feet.[89]

In July 2020, preliminary results of a National Trust survey of snail shells unearthed at the site suggested the hill figure is "medieval or later".[90] Snails dating only from the Roman period (brought from France as food) were not found at the site, while species first found in England from the 13th and 14th centuries were found in soil samples examined. In 2020 the National Trust commissioned a further survey, using optically stimulated luminescence, and the results contradicted earlier research and theories. Samples from inside the deepest layers of the monument yielded a date range for construction of 700–1100 CE – early medieval late Anglo-Saxon period.[72][91]

A 2024 study proposed that the figure depicts Hercules and was created c. 900 CE as a muster station for West Saxon armies to gather and that by the 11th-century, the figure was being reinterpreted as portraying Saint Eadwold, by the monks at the Abbey.[92]

Earthworks

editNorth-east of the head of the giant is an escarpment called Trendle Hill, on which are some earthworks now called The Trendle or Frying Pan.[93] It is a scheduled monument in its own right.[94] Antiquarian John Hutchins wrote in 1872 that "These remains are of very interesting character, and of considerable extent. They consist of circular and other earthworks, lines of defensive ramparts, an avenue, shallow excavations, and other indications of a British settlement."[95]

Unlike the giant, the earthworks belong to Lord Digby, rather than the National Trust. Its purpose is unknown; the claim that it was the site of maypole dancing, made by the former village sexton in the late 19th century, was disputed by other villagers who located the maypole site elsewhere.[96][93] It has been considered to be Roman,[93] or perhaps an Iron-Age burial mound containing the tomb of the person represented by the giant.[97][98]

Folklore

editWhatever its origin, the giant has become an important part of the culture and folklore of Dorset. Some folk stories indicate that the image is an outline of the corpse of a real giant.[60] One story says the giant came from Denmark leading an invasion of the coast, and was beheaded by the people of Cerne Abbas while he slept on the hillside.[99]

In 1808, Dorset poet William Holloway published his poem "The Giant of Trendle Hill",[7] in which the Giant is killed by the locals by piercing its heart.

Other folklore, first recorded in the Victorian era, associates the figure with fertility.[60] According to folk belief, a woman who sleeps on the figure will be blessed with fecundity, and infertility may be cured through sexual intercourse on top of the figure, especially the phallus.[60]

In popular culture

editIn modern times the giant has been used for several publicity stunts and as an advertisement. For example, Ann Bryn-Evans of the Pagan Federation recalls that the Giant has been used to promote "condoms, jeans and bicycles".[100]

In 1998, pranksters made a pair of jeans out of plastic mesh with a 21-metre (69 ft) inside leg, and fitted them to the giant[101] to publicise American jeans manufacturer Big Smith.[102] In August 2002, the BLAC advertising agency, on behalf of the Family Planning Association, rolled a large latex sheet down the Giant's phallus to promote condom use.[103][104]

As a publicity stunt for the opening of The Simpsons Movie on 16 July 2007, a figure of Homer Simpson clad in y-front underpants and brandishing a doughnut was outlined in water-based biodegradable paint to the left of the Cerne Abbas Giant. This act displeased local neopagans, who pledged to perform rain magic to wash the figure away.[105][106]

An August 2007 report, in the Dorset Echo said a man claiming to be the "Purple Phantom" had painted the Giant's penis purple. It was reported that the man was from Fathers 4 Justice, but the group denied any involvement and said they did not know who did it.[107]

In 2012, pupils and members of the local community recreated the Olympic torch on the Giant, to mark the passing of the official torch in the run-up to the 2012 London Olympics.[108]

In November 2013, the National Trust supported Movember, which raises awareness of prostate and testicular cancer. It authorised the temporary placement of a huge grass moustache on the giant. The moustache was 12 metres (39 ft) wide and 3 metres (10 ft) deep according to the designer[109] but both the National Trust and the BBC reported it as being 11 by 2.7 metres (36.1 by 8.9 ft).[110][111]

In October 2020, to promote the release of Borat Subsequent Moviefilm people added a 'mankini' and banners stating "Wear Mask." and "Save Live." on the site.[112]

The Cerne Abbas Giant has appeared in several films and TV programmes, including the title sequence of the 1986 British historical drama film Comrades,[citation needed] a 1996 episode of the Erotic Tales series "The Insatiable Mrs Kirsch", directed by Ken Russell (featuring a replica of the Giant), in 1997, the series 6 finale "Sofa" of the comedy series Men Behaving Badly, and the 2000 film Maybe Baby directed by Ben Elton.[113][114] and even appeared in one of BBC One 'Balloon' idents between 1997 and 2002.

The giant has also been depicted in multiple video games, including Pokémon Sword and Shield.[115]

In June 2023 the Oxford Cheese Company was criticised for using an image of the giant on one of its products without the distinctive phallus.[116][117][118]

Representations

editIn 1980, Devon artist Kenneth Evans-Loud planned to produce a companion 70-metre (230 ft) female figure on the opposite hill, featuring Marilyn Monroe in her iconic pose from the film The Seven Year Itch where her dress is blown by a subway grating.[119][120]

In 1989, Turner Prize-winning artist Grayson Perry designed a set of motorbike leathers inspired by the Cerne Abbas Giant.[121][122][123] In 1994, girls from Roedean School painted a 24-metre (79 ft) replica of the Giant on their playing field, the day before sports day.[124]

In 2003, pranksters created their own 23-metre (75 ft) version of the Giant on a hill in English Bicknor, Gloucestershire, but "wearing wellies, an ear of corn hanging from its mouth and a tankard of ale in its hand".[125] In 2005, the makers of Lynx deodorant created a 9.3 square metres (100.1 sq ft) advert on a field near Gatwick, featuring a copy of the Giant wearing underpants, frolicking with two scantily clad women.[126] In 2006, artist Peter John Hardwick produced a painting "The Two Dancers with the Cerne Abbas Giant, with Apologies to Picasso" which is on display at Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.[127] In 2009, the Giant was given a red nose, to publicize the BBC's Comic Relief charity event.[128] In 2011, English animators The Brothers McLeod produced a 15-second cartoon giving their take on what the Giant does when no one is watching.[129]

In 2015, the giant was used as a character in an online comic book published by Eco Comics; the giant's character appeared in various adventures accompanying a character based on St George, though his erect penis was removed from the artwork as many "outlets, particularly in the US, refuse any form of nudity in comic books".[130]

The giant's image has been reproduced on various souvenirs and local food produce labels, including for a range of beers made by the Cerne Abbas Brewery. In 2016, the BBC reported that the beer company's logo had been censored in the Houses of Parliament.[131]

Gallery

edit-

Aerial view

-

Aerial view

-

Bottom-up view

-

The Giant's phallus

-

Renovation in 2008

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Rodney Castleden, The Cerne Giant, Dorset Publishing Company, 1996, ISBN 978-0948699559, pp. 32–33

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (2023). Queens of the wild: pagan goddesses in Christian Europe an investigation. New Haven (Conn.) London: Yale University press. p. 23. ISBN 9780300273342.

In 1983, it was realized that there was no record of the Cerne Abbas Giant before the 17th century, in a valley with good previous records...

- ^ Morcom, Thomas; Gittos, Helen (1 January 2024). "The Cerne Giant in Its Early Medieval Context". Speculum. 99 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1086/727992. ISSN 0038-7134. S2CID 266375339.

- ^ "England – Dorset", Ordnance Survey map 1:10,560, Epoch 1 (1891)

- ^ a b c d Historic England, "Hill figure called The Giant (1003202)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 14 October 2012

- ^ a b William Holloway, "The Giant of Trendle Hill", The minor minstrel: or, Poetical pieces, chiefly familiar and descriptive, Printed for W. Suttaby, 1808, 182 pages, p. 140 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Hutchins, John (1973) [1742]. The History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset. Robert Douch (Contributor). Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0874713366.

- ^ Hy. Colley March M.D. F.S.A., "The Giant and the Maypole of Cerne", Proceedings, Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, Vol. 22, 1901, p. 108

- ^ Piggott, Stuart (1938). "The Hercules Myth – beginnings and ends". Antiquity. 12 (47): 323–31. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00013946. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 163883278.

- ^ Timothy Darvill, "Cerne Giant, Dorset, England Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine", in Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology, publisher: Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0199534043, 544 pages.

- ^ Hy. Colley March M.D. F.S.A., "The Giant and the Maypole of Cerne", Proceedings, Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, Vol. 22, 1901, pp. 107–08

- ^ a b Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 395. ISBN 1851094407.

- ^ "Cerne Abbas Giant & Cerne Abbas, Dorset". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Chris Court, "Nose Job for Chalk Giant", Press Association, Sunday 11 April 1993, Home News

- ^ Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture, Publisher: Verso Books, 2012, ISBN 978-1844678693, 508 pages, p. 172 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Eugene Monick, Phallos: Sacred Image of the Masculine, Volume 27 of Studies in Jungian psychology, publisher Inner City Books, 1987, ISBN 978-0919123267, 141 pages, p. 36 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Antony Barnett, "Bishop tried to gird the giant's loins Archived 13 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine", The Observer, 5 March 2000

- ^ a b "Editorial". Antiquity. 50 (198): 89–94. 1976. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00070824.

- ^ Grinsell, Leslie (1980). "The Cerne Abbas Giant: 1764–1980". Antiquity. 54 (210): 29–33. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00042824. S2CID 163711386.

- ^ a b Simpson, Craig (12 May 2021). "Rebel baron undressed the Cerne Abbas giant to get a rise out of Oliver Cromwell". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ a b John Sydenham, Baal Durotrigensis. A dissertation on the antient colossal figure at Cerne, Dorsetshire, London, W. Pickering, 1842. "Section IV" (p. 43 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Cerne Abbas Giant: Preserving an icon" Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News Dorset, 17 March 2010, retrieved 5 October 2012

- ^ "Pass notes no 2,820: The Cerne Abbas giant Archived 13 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine", The Guardian, 27 July 2010, retrieved 5 October 2012

- ^ "Visit the Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset Archived 21 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine", 6 July 2011, retrieved 5 October 2012

- ^ "Cerne Giant" Archived 28 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine at the National Trust, retrieved 5 October 2012

- ^ "A background to Cerne Abbas Archived 6 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine", Dorset County Council, retrieved 5 October 2012

- ^ "Notes of the Month", Antiquary, a magazine devoted to the study of the past (1905), Volume: 41, p. 365

- ^ Crispin Paine, Sacred Places, National Trust Books, 2006, ISBN 978-1905400157, p. 112 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lionel Fanthorpe, Patricia Fanthorpe, The World's Most Mysterious Places, Dundurn, 1999, ISBN 978-0888822062, p. 171 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Patricia Beer, Fay Godwin, Wessex: a National Trust book, published H. Hamilton, 1985, ISBN 978-0241115503, 224 pages, p. 132 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Giant's View Archived 14 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine Lay-By on the A532 in Cerne Abbas" on Google Maps, retrieved 1 November 2012

- ^ Tony Haskell, Caring for our Built Heritage: Conservation in practice: a review of conservation schemes carried out by County Councils and National Park Authorities in England and Wales in association with District Councils and other agencies, Publisher Taylor & Francis, 1993, ISBN 978-0419175803, 379 pages, pp. 20–21 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Bettey, J. H. (1981). "The Cerne Abbas Giant: the documentary evidence". Antiquity. 55 (214): 118–19. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0004391X. S2CID 163565157.

- ^ Martin Symington, Sacred Britain: A Guide to Places that Stir the Soul, publisher: Bradt Travel Guides, 2012, ISBN 978-1841623634, 240 pages, p. 53 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Katherine Barker, "Brief Encounter: The Cerne Abbas Giantess Project, Summer 1997", Proceedings – Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, Volume 119, pp. 179–83, citing Vale 1992, op.. cit [1] Archived 14 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine [2] Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vivian Vale, Patricia Vale, Book of Cerne Abbas: Abbey and After, Halsgrove Press, 2000, ISBN 978-1841140698

- ^ Francis Wise, A letter to Dr Mead concerning some antiquities in Berkshire, printed for Thomas Wood, 1738, p. 48 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e D. Morgan Evans, "Eighteenth-Century Descriptions of the Cerne Abbas Giant", The Antiquaries Journal, Volume 78, September 1998, p. 463 Archived 6 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine (−471).

- ^ a b William Stukeley, Minute Book of the Society of Antiquaries, Vol. IX, p. 233. Thursday 15 March 1764. Reproduced in Hy. Colley March M.D. F.S.A., "The Giant and the Maypole of Cerne", Proceedings, Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, Vol.22, 1901', p. 116.

- ^ a b The Gentleman's Magazine, Volume 34, July 1764, p. 336 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Gentleman's magazine, Volume 34 (August 1764). p. 335 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Haughton, Brian (2007). Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries. Franklin Lakes, NJ: New Page Books. p. 136. ISBN 978-1564148971.

- ^ Lewis, Richard (1 May 2005). "Celebrating May Day the Pagan Way". The Observer. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ Robert Dodsley, The Annual Register, 1764, p. 166 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Curtis, Thomas, ed. (1829). The London Encyclopaedia: Or, Universal Dictionary of Science, Art, Literature, and Practical Mechanics, Comprising a Popular View of the Present State of Knowledge. Illustrated by Numerous Engravings, a General Atlas, and Appropriate Diagrams. Thomas Tegg. p. 768.

- ^ Britton, John; et al. (1803). The Beauties of England and Wales, Or, Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Descriptive, of Each County. Thomas Maiden, for Vernor and Hood.

- ^ "Maps & Survey Archived 17 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine", Cerne Abbas Historical Society, retrieved 13 October 2012 (illustration Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Pitt-Rivers Estate Archive, Cerne Abbas map D/PIT/P6?1768-1798 Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine" at the National Archives, retrieved 13 October 2012

- ^ Castleden (1996) p.25

- ^ Minute Book of the Society of Antiquaries, November 1763, in Vol. IX, July 1762 – April 1765, pp. 199–200, reproduced in D. Morgan Evans (1998), "Eighteenth-Century Descriptions of the Cerne Abbas Giant", The Antiquaries Journal, 78, pp. 463–71, doi:10.1017/S000358150004508X, p. 468

- ^ John Sydenham, Baal Durotrigensis. A dissertation on the antient colossal figure at Cerne, Dorsetshire; and an attempt to illustrate the distinction between the primal Celtæ and the Celto-Belgæ of Britain: with observations on the worship of the serpent and that of the sun, London, W. Pickering, 1842. Opposite title page.

- ^ William Plenderleath, The white horses of the west of England, 1892, p. 39

- ^ Castleden (1996) p.21

- ^ Harte, Jeremy (1986). Cuckoo Pounds and Singing Barrows: The Folklore of Ancient Sites in Dorset. Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society. p. 44.

- ^ Castleden (1996) p.59

- ^ Newman (2009) p.82

- ^ Castleden (1996) p.23

- ^ a b Castleden (1996) p.19

- ^ a b c d e f g Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 395–96. ISBN 1851094407.

- ^ a b Hutchins, John (1774). The history and antiquities of the county of Dorset. Vol. 2. London: W. Bowyer and J. Nichols. pp. 293–294. OCLC 702329446.

- ^ The modern antiquarian, Julian Cope, Thorsons 1998

- ^ "Cerne Abbas", The Dorset Historic Towns Project report on Cerne Abbas Archived 3 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, "Part 3 and 4 Context and sources (pdf, 492kb)" 4.1 Previous research, p. 21

- ^ a b "Cerne Abbas Giant, Hill-Figure Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine", National Trust Historic Buildings, Sites and Monuments Record (HBSMR) Number 110511, via the English Heritage Gateway, retrieved 30 October 2012

- ^ "Cerne Giant Archived 28 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine", National Trust website, retrieved 30 October 2012

- ^ Castleden (1996), p.46

- ^ Castleden (1996), p.97

- ^ "Cerne Abbas Giant at Sacred Destinations". Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Denzil Holles, 1st Baron Holles Archived 14 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BCW Project, accessed 10-05-18

- ^ Lashmar, "No prehistoric giant step for man, but a huge insult to Cromwell Archived 13 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine", The Independent, 16-05-2000

- ^ Castleden (1996) p.49

- ^ a b c "National Trust archaeologists surprised by likely age of Cerne Abbas Giant". National Trust. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Marshall, Michael (12 May 2021). "Cerne Abbas Giant may have been carved into hill over 1000 years ago". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Raw, A. "Bawdy monks and the Cerne Abbas giant Archived 26 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine", The Guardian, 16-05-21

- ^ a b Grinsell, Leslie (1980). "The Cerne Abbas Giant: 1764–1980". Antiquity. 54 (210): 29–33. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00042824. S2CID 163711386.

- ^ Lucy Cockcroft, "Cerne Abbas giant in danger of disappearing", The Telegraph, 19 June 2008, retrieved 6 October 2012

- ^ "Volunteers restore historic giant of Cerne Abbas to his former glory Archived 13 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine", The Guardian, Tuesday 16 September 2008, retrieved 6 October 2012

- ^ "Cerne Abbas Giant", National Trust, retrieved 29 June 2011 (via the Internet Archive WayBackMachine)

- ^ Cockcroft, Lucy (19 June 2008). "Cerne Abbas giant in danger of disappearing". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ BBC (20 June 2008). "Sheep shortage hits Giant's look". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ Morris, Steven (16 September 2008). "Volunteers restore historic giant of Cerne Abbas to his former glory". The Guardian. Guardian Newspapers. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ Richard Savill, "Giant can help rare wildlife to flourish Archived 7 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine", The Telegraph, 23 June 2006, retrieved 7 October 2012

- ^ Willcox, Temple (1988). "Hard times for the Cerne Giant: 20th-century attitudes to an ancient monument". Antiquity. 62 (236): 524–26. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00074640. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 164112377.

- ^ Brian Fagan, Archaeologists: Explorers of the Human Past, Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0195119466, 192 pages, p. 72 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b W. M. F. Petrie, The Hill Figures of England Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, "III. The Giant of Cerne", Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Occasional Paper No. 7, 1926

- ^ Piggott, Stuart (1938). "The Hercules Myth – beginnings and ends". Antiquity. 12 (47): 323–31. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00013946. S2CID 163883278.

- ^ Julia De Wolf Addison, Classic Myths in Art: An Account of Greek Myths as Illustrated by Great Artists, Reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, 2003 ISBN 978-0766176706, 360 pages, p. 188 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Cerne Giant", 1979 Resistivity survey by A J Clark, A D H Bartlett and A E U David, English Heritage, National Monuments Record 1058724 Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Cerne Giant", 1995 Resistivity survey by A J Clark, A D H Bartlett and A E U David, English Heritage, 1066313 Archived 27 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Cerne Abbas Giant: Snails show chalk hill figure 'not prehistoric'". BBC News. 8 July 2020. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Kindy, David. "Scholars Are One Step Closer to Solving the Mystery of an Enormous Chalk Figure". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Morcom, Thomas; Gittos, Helen (1 January 2024). "The Cerne Giant in Its Early Medieval Context". Speculum. 99 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1086/727992. ISSN 0038-7134. S2CID 266375339.

- ^ a b c "The Trendle, Possible Roman Rectangular Earthwork Enclosure Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine", National Trust Archaeological Data Service

- ^ Historic England, "Earthworks on Giant Hill (1002725)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 25 October 2012

- ^ Hutchins (1742), quoted in Dr Wake Smart, "The Cerne Giant", Journal of the British Archaeological Association, Volume: 28, 1872, p. 65

- ^ Harte (1986), pp. 45-46

- ^ James Dyer, Southern England: an archaeological guide, publisher Noyes Press, 1973, pp. 81–82

- ^ Historic England. "The Trendle (199018)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Woolf, Daniel R. (2003). The Social Circulation of the Past: English Historical Culture 1500–1730. Oxford University Press. p. 348, footnote 178. ISBN 0199257787.

- ^ "Wish for rain to wash away Homer Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine", BBC News, Monday, 16 July 2007

- ^ "Giant's blue jeans stunt faces a pounds 5,000 demand", The Birmingham Post, 15 May 1998

- ^ Tina Rowe, "Giant cover-up is a stroke of pure jean-ius ...", Western Daily Press, 15 May 1998, p. 3

- ^ BLAC Agency for the Family Planning Association, campaign overview, retrieved 11 October 2012

- ^ "Diary: Arnold covers back in giant condom assault with UFO spotters ruse", Campaign, 9 August 2002

- ^ "Wish for rain to wash away Homer". BBC News. 16 July 2007. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ^ Hamblin, Cory (2009). Serket's Movies: Commentary and Trivia on 444 Movies. Dorrance Publishing. p. 327. ISBN 978-1434996053. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Giant daubed by 'vigilante'". Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ Ruth Meech, "Youngsters recreate Olympic torch on Cerne Abbas' chalk giant" Archived 27 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Dorset Echo, 29 May 2012, retrieved 27 October 2012

- ^ "Cerne Giant Watch our Cerne Giant Movember video". National Trust. 2013. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015. The measurements are taken from the video clip, entitled Watch our Cerne Giant Movember video. Starting at 39 seconds into the video, Richard Brown, from British Seed Houses, says, "The moustache is 12 metres long by three metres deep and it took five of us four and a half hours to construct it on the day."

- ^ "Giant support for Movember is a sight to behold". National Trust. 1 November 2013. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Cerne Abbas Giant sports moustache for Movember". BBC News. BBC. 1 November 2013. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "Cerne Abbas Giant defaced to promote new Borat movie". Dorset Echo. 23 October 2020. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Maybe Baby on YouTube End scene, retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ See the individual productions, and "The South-Central Region On Screen" Archived 4 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 12 October 2012,

- ^ Radulovic, Petrana (27 February 2019). "Is Pokémon Sword and Shield's region based on the UK?". Polygon. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Cheese logo criticised for using censored Cerne Abbas Giant". BBC News. 2 June 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ Simpson, Craig (1 June 2023). "Cheese company 'castrates' the Cerne Abbas giant". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "Uproar as cheese company 'castrates' Dorset's Cerne Abbas Giant". Dorset Echo. 2 June 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ Annabel Ferriman, "Objections to hill figure", The Times, issue No. 60571, 10 March 1980, p. 2.

- ^ Rodney Castleden, The Cerne Giant, Dorset Publishing Company, 1996, ISBN 978-0948699559, p. 37 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Naomi West, "The world of ..." Archived 4 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph, 17 February 2007, retrieved 11 October 2012

- ^ "Grayson Perry at the British Museum", The Vintage, 15 December 2011

- ^ "Saucy tips for the ladies who lunch", London Evening Standard, 10 March 2011, retrieved 11 October 2012

- ^ Jack O'Sullivan, "So you still want to send the kids to boarding school?" Archived 4 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 18 March 1999, retrieved 12 October 2012

- ^ "Pranksters Create A Naked Giant Imposter", Western Daily Press, 15 April 2003, p. 23

- ^ "Huge deodorant advert washed away", BBC News, 26 July 2005

- ^ Peter John Hardwick, "The Two Dancers with the Cerne Abbas Giant, with Apologies to Picasso" Archived 28 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, BBC Your Paintings, retrieved 12 October 2012

- ^ "Cerne Abbas Giant given red nose", BBC News Dorset, 12 February 2009, retrieved 12 October 2012

- ^ The Brothers McLeod, "Funny in 15: Cerne Abbas" Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 29 September 2011, retrieved 12 October 2012

- ^ Ward, Victoria (8 May 2015). "Giant chalk hillside figure in Cerne Abbas censored for American audience". Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "Cerne Abbas giant beer logo censored in Parliament bar" Archived 31 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 5 February 2016, retrieved 29 July 2017

Bibliography

editBooks

edit- Rodney Castleden, with a foreword by Rodney Legg, The Cerne Giant, published by Wincanton DPC, 1996, ISBN 0948699558.

- Michael A., Hodges MA., Helis, the Cerne Giant, and his links with Christchurch, Christchurch, c. 1998, 15 pp. OCLC 41548081

- Dr. T. William Wake Smart, Ancient Dorset, 1872, "The Cerne Giant," pp. 319–27. OCLC 655541806

- Darvill, T., Barker, K., Bender, B., and Hutton, R., The Cerne Giant: An Antiquity on Trial, 1999, Oxbow. ISBN 978-1900188944. [3]

- Legg, Rodney, 1990, Cerne; Giant and Village Guide, Dorset Publishing Company, 2nd edition, ISBN 978-0948699177.[4]

- Knight, Peter, The Cerne Giant – Landscape, Gods and the Stargate, 2013, Stone Seeker Publishing. ISBN 9780956034229

Journal articles

edit- Dr Wake Smart, "The Cerne Giant", Journal of the British Archaeological Association, Volume: 28, 1872.

- Hy. Colley March M.D. F.S.A., "The Giant and the Maypole of Cerne", Proceedings, Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, Vol. 22, 1901.

- W. M. F. Petrie, The Hill Figures of England, "III. The Giant of Cerne", Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Occasional Paper No. 7, 1926.

- O. G. S. Crawford, "The Giant of Cerne and other Hill-figures", Antiquity, Vol. 3 No. 11, September 1929, pp. 277–82.

- Stuart Piggott, "Notes and News: The name of the giant of Cerne", Antiquity, Vol. 6, No. 22, June 1932, pp. 214–16.

- Stuart Piggott, "The Hercules Myth – beginnings and ends", Antiquity, Vol. 12 No. 47, September 1938, pp. 323–31.

- "Editorial: regarding the Home Office file, Obscene Publications: the Cerne Abbas Giant (PRO HO 45/18033)", Antiquity, Vol.50 No.198, June 1976, pp. 93–94.

- Leslie Grinsell, "The Cern Abbas Giant 1764–1980", Antiquity, Vol. 54 No. 210, March 1980, pp. 29–33.

- J. H. Bettey, "The Cerne Abbas giant: the documentary evidence", Antiquity, Vol. 55, No. 214, July 1981, pp. 118–21.

- J. H. Bettey, "Notes and News: The Cerne Giant: another document?", Antiquity, Vol. 56 No. 216, March 1982, pp. 51–52.

- Temple Willcox, "Hard times for the Cerne Giant: 20th-century attitudes to an ancient monument", Antiquity, Vol. 62 No. 236, September 1988, pp. 524–26.

- Chris Gerrard, "Cerne Giant", British Archaeology, Issue no 55, October 2000. A review of the book: The Cerne Giant: an Antiquity on Trial by Timothy Darvill, Katherine Barker, Barbara Bender and Ronald Hutton (eds), Oxbow, ISBN 1900188945.

National Monument Records

edit- 1979 Resistivity survey by A J Clark, A D H Bartlett and A E U David, which "found evidence for the 'lion skin' feature over the giant's left arm"

- 1988–1989 Resistivity surveys, testing for the existence of possible additional features, 1988, 1989, 1994

- 1995 Resistivity survey finding evidence of a cloak, penis length change, and navel, but, not for a severed head, horns, nor lettering/symbols between the feet

- "Cerne Giant", National Monument Records, No. ST 60 SE 39 (on Pastscape.org.uk)

External links

edit- Cerne Giant at the National Trust

- Cerne Abbas giant at Mysterious Britain & Ireland

- Historic England. "Hill figure called The Giant (1003202)". National Heritage List for England.

- Historic England. "Cerne Giant (199015)". Research records (formerly PastScape).

- Cerne Abbas Giant, Hill-Figure at the National Trust Historic Buildings, Sites and Monuments Record (HBSMR)

- Cerne Abbas Giant at the Dorset Historic Environment Record (via heritagegateway.org.uk)

- "The Trendle, Possible Roman Rectangular Earthwork Enclosure" (Scheduled Monument record)

- Historian John Julius Norwich - Actress Iris Tree's efforts to become pregnant on YouTube