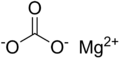

Magnesium carbonate, MgCO3 (archaic name magnesia alba), is an inorganic salt that is a colourless or white solid. Several hydrated and basic forms of magnesium carbonate also exist as minerals.

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.106 |

| E number | E504(i) (acidity regulators, ...) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| MgCO3 | |

| Molar mass | 84.3139 g/mol (anhydrous) |

| Appearance | Colourless crystals or white solid Hygroscopic |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.958 g/cm3 (anhydrous) 2.825 g/cm3 (dihydrate) 1.837 g/cm3 (trihydrate) 1.73 g/cm3 (pentahydrate) |

| Melting point | 350 °C (662 °F; 623 K) decomposes (anhydrous) 165 °C (329 °F; 438 K) (trihydrate) |

| Anhydrous: 0.0139 g/100 ml (25 °C) 0.0063 g/100 ml (100 °C)[1] | |

Solubility product (Ksp)

|

10−7.8[2] |

| Solubility | Soluble in acid, aqueous CO2 Insoluble in acetone, ammonia |

| −32.4·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.717 (anhydrous) 1.458 (dihydrate) 1.412 (trihydrate) |

| Structure | |

| Trigonal | |

| R3c, No. 167[3] | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

75.6 J/mol·K[1] |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

65.7 J/mol·K[1][4] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−1113 kJ/mol[4] |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

−1029.3 kJ/mol[1] |

| Pharmacology | |

| A02AA01 (WHO) A06AD01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

|

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0969 |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Magnesium bicarbonate |

Other cations

|

Beryllium carbonate Calcium carbonate Strontium carbonate Barium carbonate Radium carbonate |

Related compounds

|

Artinite Hydromagnesite Dypingite |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (December 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Forms

editThe most common magnesium carbonate forms are the anhydrous salt called magnesite (MgCO3), and the di, tri, and pentahydrates known as barringtonite (MgCO3·2H2O), nesquehonite (MgCO3·3H2O), and lansfordite (MgCO3·5H2O), respectively.[6] Some basic forms such as artinite (Mg2CO3(OH)2·3H2O), hydromagnesite (Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·4H2O), and dypingite (Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·5H2O) also occur as minerals. All of those minerals are colourless or white.

Magnesite consists of colourless or white trigonal crystals. The anhydrous salt is practically insoluble in water, acetone, and ammonia. All forms of magnesium carbonate react with acids. Magnesite crystallizes in the calcite structure wherein Mg2+ is surrounded by six oxygen atoms.[3]

| Carbonate coordination | Magnesium coordination | Unit cell |

|---|---|---|

The dihydrate has a triclinic structure, while the trihydrate has a monoclinic structure.

References to "light" and "heavy" magnesium carbonates actually refer to the magnesium hydroxy carbonates hydromagnesite and dypingite, respectively.[7] The "light" form is precipitated from magnesium solutions using alkali carbonate at "normal temperatures" while the "heavy" may be produced from boiling concentrated solutions followed by precipitation to dryness, washing of the precipitate, and drying at 100 C. [8]

Preparation

editMagnesium carbonate is ordinarily obtained by mining the mineral magnesite. Seventy percent of the world's supply is mined and prepared in China.[9]

Magnesium carbonate can be prepared in laboratory by reaction between any soluble magnesium salt and sodium bicarbonate:

- MgCl2(aq) + 2 NaHCO3(aq) → MgCO3(s) + 2 NaCl(aq) + H2O(l) + CO2(g)

If magnesium chloride (or sulfate) is treated with aqueous sodium carbonate, a precipitate of basic magnesium carbonate – a hydrated complex of magnesium carbonate and magnesium hydroxide – rather than magnesium carbonate itself is formed:

- 5 MgCl2(aq) + 5 Na2CO3(aq) + 5 H2O(l) → Mg4(CO3)3(OH)2·3H2O(s) + Mg(HCO3)2(aq) + 10 NaCl(aq)

High purity industrial routes include a path through magnesium bicarbonate, which can be formed by combining a slurry of magnesium hydroxide and carbon dioxide at high pressure and moderate temperature.[6] The bicarbonate is then vacuum dried, causing it to lose carbon dioxide and a molecule of water:

- Mg(OH)2 + 2 CO2 → Mg(HCO3)2

- Mg(HCO3)2 → MgCO3 + CO2 + H2O

Chemical properties

editWith acids

editLike many common group 2 metal carbonates, magnesium carbonate reacts with aqueous acids to release carbon dioxide and water:

- MgCO3 + 2 HCl → MgCl2 + CO2 + H2O

- MgCO3 + H2SO4 → MgSO4 + CO2 + H2O

Decomposition

editAt high temperatures MgCO3 decomposes to magnesium oxide and carbon dioxide. This process is important in the production of magnesium oxide.[6] This process is called calcining:

- MgCO3 → MgO + CO2 (ΔH = +118 kJ/mol)

The decomposition temperature is given as 350 °C (662 °F).[10][11] However, calcination to the oxide is generally not considered complete below 900 °C due to interfering readsorption of liberated carbon dioxide.

The hydrates of the salts lose water at different temperatures during decomposition.[12] For example, in the trihydrate MgCO3·3H2O, which molecular formula may be written as Mg(HCO3)(OH)·2H2O, the dehydration steps occur at 157 °C and 179 °C as follows:[12]

- Mg(HCO3)(OH)·2(H2O) → Mg(HCO3)(OH)·(H2O) + H2O at 157 °C

- Mg(HCO3)(OH)·(H2O) → Mg(HCO3)(OH) + H2O at 179 °C

Uses

editThe primary use of magnesium carbonate is the production of magnesium oxide by calcining. Magnesite and dolomite minerals are used to produce refractory bricks.[6] MgCO3 is also used in flooring, fireproofing, fire extinguishing compositions, cosmetics, dusting powder, and toothpaste. Other applications are as filler material, smoke suppressant in plastics, a reinforcing agent in neoprene rubber, a drying agent, and colour retention in foods.

Because of its low solubility in water and hygroscopic properties, MgCO3 was first added to table salt (NaCl) in 1911 to make it flow more freely. The Morton Salt company adopted the slogan "When it rains it pours", highlighting that its salt, which contained MgCO3, would not stick together in humid weather.[13]

Powdered magnesium carbonate, known as climbing chalk or gym chalk is also used as a drying agent on athletes' hands in rock climbing, gymnastics, powerlifting, weightlifting and other sports in which a firm grip is necessary.[9] A variant is liquid chalk.

As a food additive, magnesium carbonate is known as E504. Its only known side effect is that it may work as a laxative in high concentrations.[14]

Magnesium carbonate is used in taxidermy for whitening skulls. It can be mixed with hydrogen peroxide to create a paste, which is spread on the skull to give it a white finish.

Magnesium carbonate is used as a matte white coating for projection screens.[15]

Medical use

editIt is a laxative to loosen the bowels.

In addition, high purity magnesium carbonate is used as an antacid and as an additive in table salt to keep it free flowing. Magnesium carbonate can do this because it does not dissolve in water, only in acid, where it will effervesce (bubble).[16]

Safety

editMagnesium carbonate is non-toxic and non-flammable.

Compendial status

editSee also

edit- Calcium acetate/magnesium carbonate

- Upsalite, a reported amorphous form of magnesium carbonate

Notes and references

edit- ^ a b c d "Magnesium carbonate".

- ^ Bénézeth, Pascale; Saldi, Giuseppe D.; Dandurand, Jean-Louis; Schott, Jacques (2011). "Experimental determination of the solubility product of magnesite at 50 to 200 °C". Chemical Geology. 286 (1–2): 21–31. Bibcode:2011ChGeo.286...21B. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2011.04.016.

- ^ a b Ross, Nancy L. (1997). "The equation of state and high-pressure behavior of magnesite". Am. Mineral. 82 (7–8): 682–688. Bibcode:1997AmMin..82..682R. doi:10.2138/am-1997-7-805. S2CID 43668770.

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A22. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0373". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c d Margarete Seeger; Walter Otto; Wilhelm Flick; Friedrich Bickelhaupt; Otto S. Akkerman. "Magnesium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_595.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Botha, A.; Strydom, C.A. (2001). "Preparation of a magnesium hydroxy carbonate from magnesium hydroxide". Hydrometallurgy. 62 (3): 175. Bibcode:2001HydMe..62..175B. doi:10.1016/S0304-386X(01)00197-9.

- ^ J.R. Partington (1951). General and inorganic chemistry, 2nd ed.

- ^ a b Allf, Bradley (21 May 2018). "The Hidden Environmental Cost of Climbing Chalk". Climbing Magazine. Cruz Bay Publishing. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

In fact, China produces 70 percent of the world's magnesite. Most of that production—both mining and processing—is concentrated in a small corner of Liaoning, a hilly industrial province in northeast China between Beijing and North Korea.

- ^ "IAState MSDS".

- ^ Weast, Robert C.; et al. (1978). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (59th ed.). West Palm Beach, FL: CRC Press. p. B-133. ISBN 0-8493-0549-8.

- ^ a b "Conventional and Controlled Rate Thermal analysis of nesquehonite Mg(HCO3)(OH)·2(H2O)" (PDF).

- ^ "Her Debut - Morton Salt". Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "Food-Info.net : E-numbers : E504: Magnesium carbonates". 080419 food-info.net

- ^ Noronha, Shonan (2015). Certified Technology Specialist-Installation. McGraw Hill Education. p. 256. ISBN 978-0071835657.

- ^ "What Is Magnesium Carbonate?". Sciencing. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ British Pharmacopoeia Commission Secretariat (2009). "Index, BP 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ "Japanese Pharmacopoeia, Fifteenth Edition" (PDF). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2010.