Charles Habib Malik (Arabic: شارل حبيب مالك; sometimes spelled Charles Habib Malek;[1][2][3] 11 February 1906 – 28 December 1987) was a Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher, and politician. He served as the Lebanese representative to the United Nations, the President of the Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations General Assembly, a member of the Lebanese Cabinet, the head of the Ministry of Culture and Higher Education and of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Emigration, as well as being a theologian. He participated in the drafting of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Charles Malik | |

|---|---|

شارل مالك | |

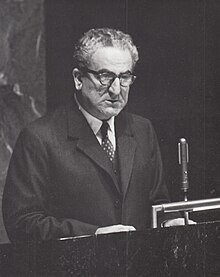

Malik in 1958 | |

| Born | February 11, 1906 Btourram, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | December 28, 1987 (aged 81) Beirut, Lebanon |

| Education | American University of Beirut, Harvard University |

| Known for | Participating in the drafting of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

Birth and education

editBorn in Btourram, Ottoman Vilayet of Beirut (present-day Lebanon), Malik was the son of Dr. Habib Malik and Dr. Zarifa Karam. Malik was the great-nephew of the renowned author Farah Antun. Malik was educated at the American Mission School for Boys, now Tripoli Evangelical School for Girls and Boys in Tripoli and the American University of Beirut, where he graduated with a degree in mathematics and physics. He moved on to Cairo in 1929, where he developed an interest in philosophy, which he proceeded to study at Harvard (under Alfred North Whitehead) and in Freiburg, Germany under Martin Heidegger in 1932. His stay in Germany, however, was short-lived. He found the policies of the Nazis unfavorable, and left soon after they came to power in 1933. In 1937, he received his Ph.D. in philosophy (based on metaphysics in the philosophies of Whitehead and Heidegger) from Harvard University. He taught there as well as at other universities in the United States. After returning to Lebanon, Malik founded the Philosophy Department at the American University of Beirut, as well as a cultural studies program (the 'civilization sequence program',[4] now 'Civilization Studies Program'). He remained in this capacity until 1945 when he was appointed to be the Lebanese Ambassador to the United States and the United Nations.

In the United Nations

editMalik represented Lebanon at the San Francisco conference at which the United Nations was founded. He served as a rapporteur for the Commission on Human Rights in 1947 and 1948, when he became president of the Economic and Social Council.[5] The same year, he became one of the eight representatives that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He competed with vice-chairman P.C. Chang over the intellectual foundations of the declaration, but later conceded to Chang's point of freedom of religion and singled his rival out without mentioning the others, which included chair Eleanor Roosevelt, during his closing and thanking speech.[6] He succeeded Roosevelt as the Human Rights Commission's Chair. He remained as ambassador to the US and UN until 1955. He was an outspoken participant in debates in the United Nations General Assembly and often criticized the Soviet Union. After a three-year absence, he returned in 1958 to preside over the thirteenth session of the United Nations General Assembly.[5]

Roles in Lebanon

editMeanwhile, Malik had been appointed to the Lebanese Cabinet. He was Minister of National Education and Fine Arts in 1956 and 1957, and Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1956 to 1958. While a Minister, he was elected to the National Assembly in 1957, and served there for three years. Around this time, he was also elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.[7][8]

Following the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War, which raged from 1975 to 1990, Malik helped to found the Front for Freedom and Man in Lebanon, which he named as such, to defend the Christian cause. It was later renamed the Lebanese Front. A Greek Orthodox Christian, he was the only non-Maronite among the Front's top leaders, who included Phalangist Party founder Pierre Gemayel and former President and National Liberal Party leader Camille Chamoun. Malik was widely regarded as the brains of the Front, in which the other politicians were the brawn.

Malik was also noted as a theologian who successfully reached across confessional lines, appealing to his fellow Greek Orthodox Christians, Catholics, and Evangelicals alike. The author of numerous commentaries on the Bible and on the writings of the early Church Fathers, Malik was one of the few Orthodox theologians of his time to be widely known in Evangelical circles, and the evangelical leader Bill Bright spoke well of him and quoted him. Partly owing to Malik's ecumenical appeal, as well as to his academic credentials, he served as President of the World Council on Christian Education from 1967 to 1971, and as vice-president of the United Bible Societies from 1966 to 1972.

Malik also famously worked alongside fellow Lebanese diplomat and philosopher Karim Azkoul.[9][10][11] He is related to founder of postcolonialism Edward Said through marriage.[12]

At a UN session in December 1948, Malik described Lebanon as follows:

"The history of my country for centuries is precisely that of a small country struggling against all odds for the maintenance and strengthening of real freedom of thought and conscience. Innumerable persecuted minorities have found, throughout the ages, a most understanding haven in my country, so that the very basis of our existence is complete respect of differences of opinion and belief."

Academic career

editMalik returned to his academic career in 1960. He traveled extensively, lectured on human rights and other subjects, and held professorships at a number of American universities including Harvard, the American University in Washington, DC, Dartmouth College (New Hampshire), University of Notre Dame (Indiana). In 1981, he was also a Pascal Lecturer at the University of Waterloo in Canada. His last official post was with The Catholic University of America (Washington, DC), where he served as a Jacques Maritain Distinguished Professor of Moral and Political Philosophy from 1981 to 1983. He also returned to his old chair in Philosophy at the American University of Beirut (1962 to 1976) and was appointed Dean of Graduate Studies. Malik has been awarded a world record of 50 honorary degrees; the originals are in his archives in Notre Dame University-Louaize, Lebanon.[citation needed]

Death

editMalik died of complications due to kidney failure, secondary to atheroembolic disease sustained after a cardiac catheterization, performed at the Mayo Clinic two years earlier, in Beirut on 28 December 1987. His son, Habib Malik, is a prominent academic (with expertise in the history of ideas, and associate professor in the humanities division at the Lebanese American University) and also a human rights activist. He was also survived by his brother, the late Father Ramzi Habib Malik, a prominent Catholic priest who worked tirelessly for the cause of Christian reconciliation with the Jewish people as well as for the belief that the Jewish People are the elder brothers of the Christians. Malik's personal papers are housed in Notre Dame University-Louaize, Lebanon, where 200 of his personal papers and books are stored, and in the Library of Congress, Washington D.C., where his heritage occupies 44 meters of shelves in the special collection area.

Further reading

edit- Mary Ann Glendon. The Forum and the Tower: How Scholars and Politicians Have Imagined the World, from Plato to Eleanor Roosevelt (2011) pp 199–220

- Charles Malik, Christ and Crisis (1962)

- Charles Malik, Man in the Struggle for Peace (1963)

- Charles Malik, The Wonder of Being (1974)

- Charles Malik, A Christian Critique of the University (1982)

- Habib Malik, The Challenge of Human Rights: Charles Malik and the Universal Declaration (2000)

Famous quotes

edit- "The fastest way to change society is to mobilize the women of the world."

- "The truth, if you want to hear it bluntly and from the start, is that independence is both a reality and a myth, and that part of its reality is precisely its myth."

- "The greatest thing about any civilization is the human person, and the greatest thing about this person is the possibility of his encounter with the person of Jesus Christ."

- "You may win every battle, but if you lose the war of ideas, you will have lost the war. You may lose every battle, but if you win the war of ideas, you will have won the war. My deepest fear--and your greatest problem--is that you may not be winning the war of ideas."

- "The great moments of the Near East are the judges of the world."

- "The university is a clear-cut fulcrum with which to move the world. More potently than by any other means, change the university and you change the world."[13]

See also

editSources

edit- ^ Awad, Najib George (2012). And Freedom Became a Public-square: Political, Sociological and Religious Overviews on the Arab Christians and the Arabic Spring. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783643902665.

- ^ Sayigh, Rosemary (2015-03-01). Yusif Sayigh: Arab Economist and Palestinian Patriot: A Fractured Life Story. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9781617976421.

- ^ "Charles Habib Malek - Les clés du Moyen-Orient". www.lesclesdumoyenorient.com. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ Now: Civilization Studies Program, AUB http://www.aub.edu.lb/fas/cvsp/Pages/index.aspx Archived 2017-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "DR. CHARLES HABIB MALIK - 13th Session". United Nations. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights" (PDF).

- ^ "Charles Habib Malik". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ Elias, Amin. "La liberté de conversion : le débat dans l'Islam est désormais quotidien". Fondazione Internazionale Oasis. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Photo/YES, UN (1958-08-19). "General Assembly Continues Middle East Debate". www.unmultimedia.org. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ^ Photo/TW, UN (1957-09-25). "Lebanese Delegation to the 12th Session of the UN General Assembly". www.unmultimedia.org. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ^ Said, Edward W. (1999). Out of Place. Vintage Books, NY.

- ^ "Around the World | Central Kentucky CRU". Archived from the original on 2013-09-28. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

External links

edit- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Dr Charles Malik" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- Charles Malek's biography in his hometown Bterram website