Charles Samuel Addams (January 7, 1912 – September 29, 1988) was an American cartoonist known for his darkly humorous and macabre characters.[1] Some of his recurring characters became known as the Addams Family, and were subsequently popularized through various adaptations.

| Charles Addams | |

|---|---|

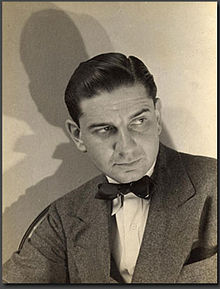

Addams in 1947 | |

| Born | Charles Samuel Addams January 7, 1912 Westfield, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | September 29, 1988 (aged 76) New York City, U.S. |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist |

| Pseudonym(s) | Chas Addams (pen name/nickname) |

Notable works | The Addams Family |

| Awards | |

| Spouse(s) | Estelle Barbara Barb

(m. 1954; div. 1956)Marilyn Matthews Miller

(m. 1981) |

Early life

editAddams was born in Westfield, New Jersey. He was the son of Grace M. (née Spear; 1879–1943) and Charles Huey Addams (1873–1932), a piano company executive who had studied to be an architect.[2] Known as "something of a rascal around the neighborhood," as childhood friends recalled,[3] Addams was distantly related to U.S. presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, despite the different spellings of their last names, and was a first cousin twice removed to noted social reformer Jane Addams.[3][4]

Addams would enjoy the Presbyterian Cemetery on Mountain Avenue in Westfield as a child, where – according to author and Addams expert Ron MacCloskey – he would wonder what it was like to be dead.[5] In the cartoons, his ghoulish creations lived on Cemetery Ridge with a dreadful view.

A house on Elm Street and another on Dudley Avenue – into which police once caught him breaking and entering – are said to be the inspiration for the Addams Family mansion in his cartoons. College Hall, the oldest building on the current campus of the University of Pennsylvania, where Addams studied, was also an inspiration for the mansion.[6] One friend said of him: "His sense of humor was a little different from everybody else's." He was also artistically inclined, "drawing with a happy vengeance", according to a biographer.[3]

His father encouraged him to draw, and Addams did cartoons for the Westfield High School yearbook, Weathervane.[2][5] He attended Colgate University in 1929 and 1930. At the corners of West Kendrick and Maple Avenues in Hamilton, is another home, and myth, that may have inspired the Addams Family house.[7] He also attended the University of Pennsylvania in 1930 and 1931. He then studied at the Grand Central School of Art in New York City in 1931 and 1932.[2][5]

Career

editCharles Addams joined the layout department of True Detective magazine in 1933, where he retouched photos of corpses to remove the blood for appearance alongside magazine stories. Addams complained: "A lot of those corpses were more interesting the way they were."[8]

The New Yorker Obituary of October 17, 1988 says his first drawing for The New Yorker, ran February, 1932. However, his first drawing actually appeared in the February 4, 1933 issue. Here he drew the first in the series that came to be called The Addams Family in August 6, 1938 and ran regularly until his death. Addams remained a freelancer throughout that time.[3]

During World War II, Addams served at the Signal Corps Photographic Center in New York, where he made animated training films for the U.S. Army.[9]

Addams created a 1952 mural for the library at Penn State depicting prominent Addams Family members.[10]

Television producer David Levy approached Addams with an offer to create The Addams Family television series, with a little help from the humorist.[11] Addams gave his characters names as well as qualities for actors to use in portrayals; the series ran on ABC from 1964 to 1966.[5]

Cartoons

editAddams regularly had cartoons in The New Yorker, and he also created the syndicated single-panel comic Out of This World between 1955 and 1957. Collections of his work include Drawn and Quartered (1942) and Monster Rally (1950), the latter with a foreword by John O'Hara.[12] One cartoon shows two men standing in a patent attorney's office; one points a bizarre gun out the window toward the street, saying: "Death ray, fiddlesticks! Why, it doesn't even slow them up!".[13]

Dear Dead Days (1959) is a scrapbook-like compendium of vintage images (and occasional pieces of text) that appealed to the author's sense of the grotesque, including Victorian woodcuts, vintage medicine-show advertisements, and a boyhood photograph of Francesco Lentini, who had three legs.[14]

Addams drew more than 1,300 cartoons over the course of his life. Beyond The New Yorker pages, his cartoons appeared in Collier's and TV Guide,[5] as well as books, calendars, and other merchandise.

The 1957 album Ghost Ballads, featuring folk songs with supernatural themes by singer-guitarist Dean Gitter, was packaged with cover art by Addams depicting a haunted house.[15]

The Mystery Writers of America honored Addams with a Special Edgar Award in 1961 for his body of work. The films The Old Dark House (1963) and Murder by Death (1976) feature title sequences illustrated by Addams.[16]

In 1946, Addams met science-fiction writer Ray Bradbury after having drawn an illustration for Mademoiselle magazine's publication of Bradbury's short story "Homecoming", the first in a series of tales chronicling a family of Illinois vampires named the Elliotts. The pair became friends and planned to collaborate on a book of the Elliott Family's complete history with Bradbury writing and Addams providing the illustrations, but it never materialized. Bradbury's stories about the "Elliott Family" were finally anthologized in From the Dust Returned in October 2001, with a connecting narrative and an explanation of his work with Addams, and Addams's 1946 Mademoiselle illustration used for the book's cover jacket. Although Addams's own characters were well-established by the time of their initial encounter, in a 2001 interview, Bradbury stated: "[Addams] went his way and created the Addams Family, and I went my own way and created my family in this book."[17]

Janet Maslin, in a review of an Addams biography for The New York Times, wrote: "Addams's persona sounds cooked up for the benefit of feature writers ... was at least partly a character contrived for the public eye," noting that one outré publicity photo showed the humorist wearing a suit of armor at home, "but the shelves behind him hold books about painting and antiques, as well as a novel by John Updike."[3]

Filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock was a friend of Addams, and owned two pieces of original Addams art.[18] Hitchcock references Addams in his 1959 film North by Northwest. During the auction scene, Cary Grant discovers two of his adversaries with someone who he also thinks is against him and says: "The three of you together. Now that's a picture only Charles Addams could draw."[19]

Personal life

editAddams met first wife Barbara Jean Day in late 1943, who purportedly resembled his cartoon character Morticia Addams.[3] The marriage ended eight years later after Addams declined to have children (she later married New Yorker colleague John Hersey, author of the book Hiroshima).[20]

Addams married second wife Barbara Barb (Estelle B. Barb) in 1954. A practicing lawyer, she "combined Morticia-like looks with diabolical legal scheming," by which she wound up controlling the Addams Family television and film franchises and persuaded her husband to give away other legal rights.[3] At one point, she got her husband to take out a US$100,000 insurance policy. Addams consulted a lawyer on the sly, who later humorously wrote: "I told him the last time I had word of such a move was in a picture called Double Indemnity starring Barbara Stanwyck, which I called to his attention." In the movie, Stanwyck's character plotted her husband's murder.[3] The couple divorced in 1956.[21]

Addams was "sociable and debonair". A biographer described him as being "a well-dressed, courtly man with silvery back-combed hair and a gentle manner, he bore no resemblance to a fiend". Figuratively a "ladykiller", Addams accompanied women such as Greta Garbo, Joan Fontaine, and Jacqueline Kennedy on social occasions.[3] For about a year after the death of Nelson Rockefeller, Addams dated Megan Marshack, the aide who was with the former US vice president when he died.

Addams married his third and final wife Marilyn Matthews Miller, best known as "Tee" (1926–2002), in a pet cemetery.[2] The Addamses moved to Sagaponack, New York in 1985, where they named their estate "The Swamp".[22]

Death

editAddams died on September 29, 1988, at the age of 76, at St. Clare's Hospital and Health Center in New York City, having suffered a heart attack after parking his automobile. An ambulance took him from his apartment to the hospital, where he died in the emergency room.[2] As he had requested, a wake was held rather than a funeral; he had wished to be remembered as a "good cartoonist". In accordance with Addams's wishes, he was cremated, and his ashes were interred in the pet cemetery of "The Swamp" estate.[23]

Legacy

editThe Tee & Charles Addams foundation was established in 1999 "to interpret and share the artistic achievement of Charles Addams’s life through exhibitions and programs developed from all works by Charles Addams including the Foundation’s own collections and from its copyrights of the Addams oeuvre." Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the foundation offered tours of the couples' property and displayed artefacts from Addams' life.[24]

The Charles Addams Fine Arts Hall in Philadelphia was named in his tribute by the University of Pennsylvania in 2001.[25]

On the occasion of his 100th birthday, January 7, 2012, Charles Addams was honored with a Google Doodle.[26]

Addams was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2020.[27]

On April 30, 2021, the original art for his macabre holiday illustration "Addams and Evil", a 1947 interior book cartoon from The Addams Family Christmas, sold for $87,500, the author's world auction record, over seven times initial estimates.[28]

Works

editBooks of Addams's drawings or illustrated by him:[29] Addams also illustrated two books by other authors. First was But Who Wakes the Bugler? (Houghton & Mifflin, 1940) by Peter DeVries.[30] The other was Afternoon In the Attic (Dodd, Mead, 1950) by John Kobler.[31] He also provided the cover art for such books as The Compleat Practical Joker (Doubleday, 1953) by H. Allen Smith and Here at The New Yorker (Random House, 1975) by Brendan Gill.[32]

- (illustrations) But Who Wakes the Bugler? (1940) by Peter DeVries

- Drawn and Quartered (1942), first anthology of drawings/cartoons (Random House); re-released 1962 (Simon & Schuster)

- Addams and Evil (1947), second anthology (Simon and Schuster)

- (illustrations) Afternoon in the Attic (1950), John Kobler's collection of short stories

- Monster Rally (1950) third anthology of drawings (Simon & Schuster)

- Homebodies (1954), fourth anthology (Simon & Schuster)

- Nightcrawlers (1957), fifth anthology (Simon & Schuster)

- Dear Dead Days: A Family Album (1959), compilation book of photos (G.P. Putnam & Sons)

- Black Maria (1960), sixth anthology of drawings (Simon & Schuster)

- The Groaning Board (1964), seventh anthology (Simon & Schuster)

- The Chas Addams Mother Goose (1967), Windmill Books; reissued with additional material 2002

- My Crowd (1970), eighth anthology of drawings (Simon & Schuster)

- Favorite Haunts (1976), ninth anthology (Simon & Schuster)

- Creature Comforts (1981), tenth anthology (Simon & Schuster)

- The World of Charles Addams, by Charles Addams (1991), posthumously compiled from works with the copyright owned by his third wife, Marilyn Matthews "Tee" Addams (Knopf) ISBN 0-394-58822-3

- Chas Addams Half-Baked Cookbook: Culinary Cartoons for the Humorously Famished, by Charles Addams (2005), anthology of drawings, some previously unpublished (Simon & Schuster) ISBN 0-7432-6775-3

- Happily Ever After: A Collection of Cartoons to Chill the Heart of Your Loved One, by Charles Addams (2006), anthology of drawings, some previously unpublished (Simon & Schuster) ISBN 978-0-7432-6777-9

- The Addams Family: An Evilution (2010), about the evolution of The Addams Family characters; arranged by H. Kevin Miserocchi (Pomegranate) ISBN 978-0-7649-5388-0

- Addams' Apple: The New York Cartoons of Charles Addams (2020), anthology of drawings (Pomegranate) ISBN 978-0764999369

See also

editContemporary American cartoonists with similar macabre style include:

References

editNotes

- ^ "Macabre Cartoonist Charles Addams Dies". Los Angeles Times. September 30, 1988. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Pace, Eric (September 30, 1988). "Charles Addams Dead at 76; Found Humor in the Macabre". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Maslin, Janet (October 26, 2006). "In Search of the Dark Muse of a Master of the Macabre". The New York Times. p. E9. Retrieved October 26, 2006.

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e MacCloskey, Ron. "Charles Addams". WestfieldNJ.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ "Virtual Tour of Penn's Campus: College Hall". Archived from the original on June 6, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ "battle to save Hamilton home". Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Marr, John. "True Detective R.I.P." Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Kratz, Jessie (October 26, 2022). "Private Charles Samuel Addams: Creator of the Addams Family". Pieces of History. U.S. National Archives. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ Karasik, Paul. "Sketchbook: The Addams Family Secret: How a massive painting by Charles Addams wound up hidden away in a university library". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ "David Levy; Producer Created Addams Family", Los Angeles Times, January 31, 2000

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 362.

- ^ Williams, Christian (November 17, 1982). "Charles Addams". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Knudde, Kjell. "Charles Addams". Lambiek Comicobedia. Lambiek. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ Jason (February 28, 2004). "Scar Stuff: Dean Gitter "Ghost Ballads" (Riverside, RLP 12-636, 1957)". Scar Stuff. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ Maxford, Howard (2019). Hammer Complete: The Films, the Personnel, the Company. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4766-7007-2.

- ^ "Ray Bradbury Interview Part 1". IndieBound. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ Davis, Linda H. (December 3, 2006). "First Chapter: 'Charles Addams'". The New York Times. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Hitchcock, Alfred (director); Cary Grant (actor) (1954). North by Northwest (DVD). Burbank: Warner Home Video, Inc. Event occurs at 1:26:42.

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 106.

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 136.

- ^ Miserocchi, H. Kevin, ed. (2010). The Addams Family: An Evilution. Pomegranate Communications, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-7649-5388-0.

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 318.

- ^ "History". Tee & Charles Addams Foundation.

- ^ Connaughton, Clare (February 21, 2015). "Charles Addams 'spooky' legacy lives on in Fine Arts community". The Daily Pennsylvanian. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Charles Addams' 100th Birthday". Google. January 7, 2012. Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ Kadosh, Matt (August 7, 2020). "Westfield's Dr. Virginia Apgar, Charles Addams Make NJ Hall of Fame". TAPinto. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Vargas pinup commands $100K at Heritage sale". liveauctioneers.com. May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Author unknown (date unknown). Tee and Charles Addams Foundation. Retrieved on October 26, 2006, from "Career Biography of Charles Samuel Addams". Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2006.

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 67.

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 324.

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 234.

Bibliography

- Davis, Linda H. (2006). Chas Addams: A Cartoonist's Life. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-46325-2. Hardcover reissue, Turner, 2021

- Obituary, The New York Times, Sept. 30, 1988, p. A1

- Strickler, Dave. Syndicated Comic Strips and Artists, 1924-1995: The Complete Index. Cambria, CA: Comics Access, 1995. ISBN 0-9700077-0-1.

- "The Charms of the Macabre: Charles Addams's cartoon world is full of loving and caring people. How odd." The Wall Street Journal book review of The Addams Family: An Evilution, edited by H. Kevin Miserocchi.

External links

edit- Charles Addams Foundation

- Charles Addams at Library of Congress, with 28 library catalog records