This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2021) |

The Cheat Mountain salamander (Plethodon nettingi) is a species of small woodland salamander in the family Plethodontidae. The species is found only on Cheat Mountain, and a few nearby mountains, in the eastern highlands of West Virginia.[1][4] It and the West Virginia spring salamander (Gyrinophilus subterraneus) are the only vertebrate species with geographic ranges restricted to that state.

| Cheat Mountain salamander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Plethodontidae |

| Subfamily: | Plethodontinae |

| Genus: | Plethodon |

| Species: | P. nettingi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Plethodon nettingi Green, 1938

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

The Cheat Mountain salamander has decreased in population due to destruction of its original red spruce forest habitat, as well as by pollution, drought, forest storm damage, and by competition with other salamanders, especially its relative, the red-backed salamander (P. cinereus).

Description

editThe Cheat Mountain salamander is smallish, similar in size to the red-backed salamander, 3 to 4¾ inches (7½ to 12 cm) in total length (including tail), but is distinct in its black or dark brown dorsum (back) which is boldly marked with numerous small brassy, silver or white flecks. It lacks a dorsal stripe. The belly is dark gray to black. The tail is about the same length as its body, which has 17 to 19 costal grooves (vertical grooves along its sides).

Etymology and taxonomy

editThe specific name, nettingi, is in honor of American herpetologist M. Graham Netting.[5] P. nettingi was discovered by Netting and Leonard Llewellyn on White Top, a summit of Cheat Mountain in Randolph County, West Virginia, in 1935. It was described and named by N. Bayard Green in 1938.[6] This salamander and the Peaks of Otter salamander (P. hubrichti), which has a similarly restricted range in Virginia, were once considered subspecies of a single species, "Netting's salamander", but since 1979 they (along with the Shenandoah salamander, P. shenandoah) have been considered separate, full species. Their geographic ranges were probably much larger in the past. The circumstances surrounding the discovery and formal description of P. nettingi are related by Maurice Brooks in his classic natural history book, The Appalachians (1965).

Geographic range

editP. nettingi is restricted to a small portion of the high Allegheny Mountains in eastern West Virginia. Initially, in the 1930s and '40s, its range was thought to be limited to Cheat Mountain at elevations above 3,500 feet (1,100 m) in Randolph County — and in Pocahontas County, where it was also found at Thorny Flat (Cheat's highest point). Later inventories, conducted in the 1970s and ‘80s, expanded the known range to include Pendleton and Tucker Counties (e.g., Backbone Mountain, Dolly Sods). More recently, the range has been shown to include the eastern edge of Grant County where it is found as low as 2,640 feet (800 m) elevation. Most populations are found above 3,500 feet (1,100 m). The entire P. nettingi range encompasses only about 935 square miles (2,420 km2), but not continuously throughout even this area (about 60 isolated populations are known). Much of this range is within the Monongahela National Forest.

Habitat

editOriginally, the Cheat Mountain salamander was probably restricted to red spruce forests of West Virginia's higher mountains. Most of these forests were cut down by 1920, and so several populations today occur in mixed deciduous forests that have replaced red spruce stands. These include yellow birch, American beech, sugar maple, striped maple and eastern hemlock trees. The salamander's occurrence, however, is not dependent upon any particular type of vegetation, but is often associated with boulder fields, rock outcrops, or steep, shaded ravines lined with a dense growth of rhododendron. It is more abundant adjacent to large emergent rocks where soil and litter are more moist and cooler than the surrounding hillsides. It may be that it was protected in these refugia (emergent rocks) when the original forests were cut and in some areas burned. Typically, it is found where the ground cover consists of bryophytes (mosses, liverworts, etc. – especially the liverwort Bazzania) and an abundance of leaf litter, fallen logs and sticks.

Life history and behavior

editBehavior

editCheat Mountain salamanders spend the winter underground where temperatures remain above freezing. Depending on soil temperature, they emerge from winter refugia at the end of March or early April and retreat to underground refugia again in mid-October. During the above ground period, they are especially active at night in humid weather. During the day, they remain under rocks and in or under logs; and sometimes among wet leaves. Aestivation only occurs during unusual drought conditions.

Diet

editLike other woodland salamanders, P. nettingi subsists on mites, springtails, beetles, flies, and ants. On moist evenings it searches the forest floor, rocks and logs for food. It will occasionally climb trees, shrubs and stumps in pursuit of a meal.

Reproduction

editThe breeding behavior of P. nettingi has not been directly observed, but most likely occurs on the forest floor. Pairs of males and females have been found together under rocks in both spring and autumn and both sexes during these months are in breeding condition: males with swollen cloacas and squared-off snouts, females with mature follicles. Nesting activities are similar to the red-backed Salamander. The female typically lays 8 to 10 eggs (minimum 4; maximum 17) which are attached to the inside of a rotten log or the underside of a rock or log in either red spruce or deciduous forests. Females attending small clusters of eggs have been found from late April through early September. The female apparently guards the eggs until they hatch (a behavior unique to salamanders of the woodland salamander family, Plethodontidae). The young undergo their larval stage within the egg so that they resemble small adults when they hatch in late August or September.

The juveniles reach sexual maturity in 3 to 4 years and live for approximately 20 years. The young may remain in the same area as the adults until they become mature at which time they move away and establish their own territories. Territories are about 48 square feet (4.5 m2) in area. Woodland salamanders seldom leave their territories and, as a result, move only a few meters during their lives.

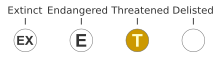

Conservation

editPopulations of the Cheat Mountain salamander probably plummeted when its original habitat (red spruce forests) was destroyed by logging in the early 20th century. It is now on the U.S. Endangered Species List and it has been protected under the Federal Endangered Species Act since 1989 as a threatened species.[2][3] Any disturbance exposing the forest floor to sunlight changes the cool, moist conditions on which these animals depend for nest sites as well as food and respiration. Alterations as minor as clearing service roads or hiking or skiing trails can fragment and isolate populations since these salamanders do not cross bare surfaces. As populations become divided, gene pools decline as does the likelihood of viability. Such habitat alterations probably also favor the encroachment of mountain dusky and red-back salamanders which out-compete the Cheat Mountain salamander for food, cover and moisture.

Fortunately, much of the Cheat Mountain salamander's range (46 of 60 known populations) falls within the Monongahela National Forest. A recovery plan was developed for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and annual surveys are conducted by Thomas K. Pauley (Marshall University), an authority on this species. He indicates that its numbers appear to be stable except where habitats have been altered. The West Virginia Division of Natural Resources has also conducted population monitoring and surveys. Since both the salamander and its habitat are monitored and protected in the National Forest and the Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge, its future looks hopeful.

References

editCitations

edit- ^ a b IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Plethodon nettingi ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T17627A118974534. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Cheat Mountain salamander (Plethodon nettingi) ". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b 54 FR 34464

- ^ a b Frost, Darrel R. (2021). "Plethodon nettingi Green, 1938". Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference. Version 6.1. American Museum of Natural History. doi:10.5531/db.vz.0001. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2013). The Eponym Dictionary of Amphibians. Exeter, England: Pelagic Publishing. xiii + 244 pp. ISBN 978-1-907807-41-1. (Plethodon nettingi, p. 154).

- ^ Green, N.B. (1938). "A New Salamander, Plethodon nettingi, from West Virginia". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 27: 295–299. doi:10.5962/p.214438. S2CID 196680149.

Other sources

edit- Brooks, M. (1948). "Notes on the Cheat Mountain salamander". Copeia. 1948 (4): 239–244. doi:10.2307/1438709. JSTOR 1438709.

- Brooks, Maurice (1965). The Appalachians. Series: The Naturalist's America. Illustrated by Lois Darling and Lo Brooks. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 346 pp. ISBN 978-0395074589.

- Green, N.B., and T.K. Pauley (1987). Amphibians and Reptiles in West Virginia. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. xi + 241 pp.

- Highton, R. (1986). "Plethodon nettingi ". Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 383: 1–2.

- Highton, Richard; Larson, Allan (1979). "The Genetic Relationships of the Salamanders of the Genus Plethodon". Systematic Zoology. 28 (4): 579–599. doi:10.2307/2412569. JSTOR 2412569.

- Mahoney, Meredith J. (2001). "Molecular Systematics of Plethodon and Aneides (Caudata: Plethodontini): phylogenetic analysis of an old and rapid radiation". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 18 (2): 174–188. doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0880. PMID 11161754.

- Martof, Bernard S., William M. Palmer, Joseph R. Bailey, and Julian R. Harrison, III (1980). Amphibians and Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. 264 pp.

- Pauley, T.K. (1985). "Distribution and Status of the Cheat Mountain Salamander". Status survey report submitted to USFWS, Dec. 1985 and Jan. 1986.

- Pauley, T.K. (1993). "Amphibians and Reptiles of the Upland Forests". pp. 179–196. In: Stephenson, Steven L. (editor) (1993). Upland Forests of West Virginia. Parsons, West Virginia: McClain Printing Company. 295 pp. ISBN 978-0870125096.

- Lannoo, Michael (editor) (2005). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

External links

editPhotos

edit- NPWRC of the USGS webpage on the CMS

- Marshall University Herpetology Lab webpage on the CMS

- eNature webpage on the CMS

- West Virginia Wildlife Magazine webpage on the CMS

Range map

edit