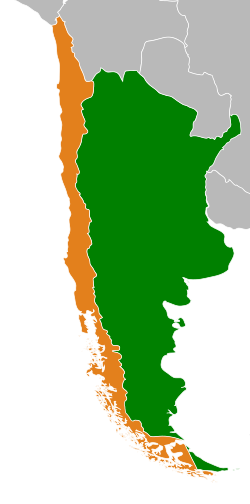

International relations between the Republic of Chile and the Argentine Republic have existed for decades. The border between the two countries is the world's third-longest international border, which is 5,300 km (3,300 mi) long and runs from north to south along the Andes mountains. Although both countries gained their independence during the South American wars of liberation, during much of the 19th and the 20th century, relations between the countries were tense as a result of disputes over the border in Patagonia. Despite this, Chile and Argentina have never been engaged in a war with each other. In recent years, relations have improved. Argentina and Chile have followed quite different economic policies. Chile has signed free trade agreements with countries such as China, the United States, Canada, South Korea, as well as European Union, and it's a member of the APEC. Argentina belongs to the Mercosur regional free trade area. In April 2018, both countries suspended their membership from the UNASUR.

| |

Argentina |

Chile |

|---|---|

Historical relations (1550–1989)

editRule under Spain and Independence

editThe relationship between the two countries can be traced back to an alliance during Spanish colonial times. Both colonies were offshoots of the Viceroyalty of Peru, with the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (which Argentina was a part of) being broken off in 1776, and Chile not being broken off until independence. Argentina and Chile were colonized by different processes. Chile was conquered as a southward extension of the original conquest of Peru, while Argentina was colonized from Peru, Chile and from the Atlantic.

Argentina and Chile were close allies during the wars of independence from the Spanish Empire. Chile, like most of the revolting colonies, was defeated at a point by Spanish armies, while Argentina remained independent throughout its war of independence. After the Chilean defeat in the Disaster of Rancagua, the remnants of the Chilean Army led by Bernardo O'Higgins took refuge in Mendoza. Argentine General José de San Martín, by that time governor of the region, included the Chilean exiles in the Army of the Andes, and in 1817 led the crossing of the Andes, defeated the Spaniards, and confirmed the Chilean Independence. While he was in Santiago, Chile a cabildo abierto (open town hall meeting) offered San Martín the governorship of Chile, which he declined, in order to continue the liberating campaign in Peru.

In 1817 Chile began the buildup of its Navy in order to carry the war to the Viceroyalty of Perú. Chile and Argentina signed a treaty in order to finance the enterprise.[1] But Argentina, fallen in a civil war, was unable to contribute. The naval fleet, after being built, launched a sea campaign to fight the Spanish fleet in the Pacific to liberate Peru. After a successful land and sea campaign, San Martín proclaimed the Independence of Peru in 1821.

War against the Peru–Bolivian Confederation

editFrom 1836 to 1839, Chile and Argentina united in a war against the confederation of Peru and Bolivia. The underlying cause was the apprehension of Chile and Argentina against the potential power of the Peru-Bolivia bloc. This resulted from concern over the large territory of Peru-Bolivia as well as the perceived threat that such a rich state would represent to their southern neighbors. Chile declared the war on 11 November 1836 and Argentina on 19 May 1837.[2]: 263ff

In 1837 Felipe Braun, one of Santa Cruz's most capable generals and highly decorated veteran of the war of independence, defeated an Argentine army sent to topple Santa Cruz. On 12 November 1838 Argentine representatives signed an agreement with the Bolivian troops.[2]: 271 However, on 20 January 1839 the Chilean force obtained a decisive victory against Peru-Bolivia at the Battle of Yungay and the short-lived Peru-Bolivian Confederation came to an end.

Chincha's war

editA series of coastal and high-seas naval battles between Spain and its former colonies of Peru and Chile occurred between 1864 and 1866. These actions began with Spain's seizure of the guano-rich Chincha Islands, part of a strategy by Isabel II of Spain to reassert her country's lost influence in Spain's former South American empire. These actions prompted an alliance between Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Chile against Spain. As a result, all Pacific coast ports of South America situated south of Colombia were closed to the Spanish fleet. Argentina, however, refused to join the alliance and maintained amicable relations with Spain[3] and delivered coal to the Spanish fleet.

War of the Pacific

editOn 6 February 1873, Peru and Bolivia signed a secret treaty of alliance against Chile.[4] On 24 September, Argentine president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento asked the Argentine Chamber of Deputies to join Argentina with the alliance. The Argentine chamber assented by a vote of 48–18. The treaty made available a credit of six million pesos for military expenditures. However, in 1874, after the delivery of the Chilean ironclad Almirante Cochrane and the ironclad Blanco Encalada, the Argentine Senate postponed the matter until late 1874, and Sarmiento was prevented signing the treaty.[5] Consequently, Argentina remained neutral during the war; and the Argentines signed a Border Treaty with Chile in 1881.

Claims on Patagonia

editBorder disputes continued between Chile and Argentina, as Patagonia was then a largely unexplored area. The Border Treaty of 1881 established the line of highest mountains dividing the Atlantic and Pacific watersheds as the border between Argentina and Chile. This principle was easily applied in northern Andean border region; but in Patagonia drainage basins crossed the Andes. This led to further disputes over whether the Andean peaks would constitute the frontier (favoring Argentina) or the drainage basins (favoring Chile). Argentina argued that previous documents referring to the boundary always mentioned the Snowy Cordillera as the frontier and not the continental divide. The Argentine explorer Francisco Perito Moreno suggested that many Patagonian lakes draining to the Pacific were in fact part of the Atlantic basin but had been moraine-dammed during the quaternary glaciations changing their outlets to the west. In 1902, war was again avoided when British King Edward VII agreed to mediate between the two nations. He cleverly established the current Argentina-Chile border in Patagonia by dividing many disputed lakes into two equal parts. Several of these lakes still have different names on each side of the frontier, such as the lake known in Chile as Lago O'Higgins and in Argentina as Lago San Martín. A dispute that arose in the northern Puna de Atacama was resolved with the Puna de Atacama Lawsuit of 1899.

1893 Border protocol

editThe 1893 Boundary Protocol between Argentina and Chile, also known as the Errázuriz-Quirno Costa Protocol, was an agreement signed by Isidoro Errázuriz Errázuriz Errázuriz representing Chile and Norberto Camilo Quirno Costa representing Argentina on May 1, 1893 in Santiago, Chile. It was signed to solve problems that arose during the demarcation of the boundary on the basis of the 1881 Treaty.

This protocol ratified the principle of “Chile to the Pacific and Argentina to the Atlantic” from which, later on, discrepancies arose regarding the limit of both oceans, and whether the principle applies to the south of parallel 52° or not, according to the protocol, it applies to the north of parallel 52° only. In addition, the principle of the “main chain” of the Andes Mountains was established. The areas affected by the protocol were: the Seno Ultima Esperanza and the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego.

Southern Patagonian Ice Field border definition in 1898 by experts from both countries

editThe area was delimited by the Treaty of 1881 between Argentina and Chile[10]

The boundary between Chile and the Argentine Republic is, from North to South, up to the fifty-second parallel of latitude, the Andes Mountain Range. The boundary line shall run in that extension along the highest peaks of said Cordillera dividing the waters, and shall pass between the slopes that break off on one side and the other. The difficulties that may arise due to the existence of certain valleys formed by the bifurcation of the Cordillera and where the dividing line of the waters is not clear, shall be resolved amicably by two experts appointed, one from each party. In case they do not reach an agreement, a third Expert appointed by both Governments shall be called upon to decide them. Of the operations carried out by them, a record shall be drawn up in duplicate, signed by the two Experts, on the points on which they have agreed, and also by the third Expert on the points decided by him. These minutes shall take full effect as soon as they have been signed by them and shall be considered firm and valid without the need for any other formalities or formalities. A copy of the minutes shall be sent to each of the Governments.[11]

On 20 August 1888, an agreement was signed to carry out the demarcation of the limits according to the 1881 treaty, appointing the experts Diego Barros Arana for Chile and Octavio Pico Burgess for Argentina.[12] In 1892, Barros Arana presented his thesis according to which the 1881 treaty had fixed the limit in the continental divortium aquarum, which was rejected by the Argentine expert.[13]

Experts have shown that it is always convenient to take the mountain as a support for the boundary and not the watershed. Rey Balmaceda tells an anecdote of Perito Moreno, who diverted the course of the Fénix River, with the help of a crew of laborers, so that it would stop heading toward the Pacific and would swell the waters of the Deseado River. With this, Moreno wanted to demonstrate that the true basis for drawing a solid and efficient line is the mountains and not the course of the waters.[14]

Because differences arose on several points of the border on which the experts could not agree, the demarcation was suspended in February 1892, until the Boundary Protocol between Chile and Argentina 1893 was subscribed, which in its article 1 provides:Article One of the Treaty of July 23, 1881, stipulating that "the boundary between Chile and the Argentine Republic is from North to South up to the 52nd parallel of latitude, the Andes Cordillera", and that "the boundary line shall run along the highest peaks of the said Cordillera, dividing the waters, and that it shall pass between the slopes that break off on either side", the Experts and the Sub-Commissions shall have this principle as the invariable rule of their proceedings. Consequently, all lands and all waters, namely: lakes, lagoons, rivers and parts of rivers, streams and slopes east of the line of the highest peaks of the Andes Mountains dividing the waters, shall be considered in perpetuity as property and absolute domain of the Argentine Republic, and all lands and all waters, namely: lakes, lagoons, rivers and parts of rivers, streams and slopes east of the highest peaks of the Andes Mountains dividing the waters, shall be considered as property and absolute domain of Chile: lakes, lagoons, rivers, and parts of rivers, streams, slopes, which are found to the west of the highest peaks of the Andes Mountains that divide the waters.[15]

This protocol is of particular importance, as the retreat of the glaciers could allow Pacific fjords to penetrate into Argentine territory.[16]

In January 1894, the Chilean expert declared that he understood that the main chain of the Andes was the uninterrupted line of peaks that divide the waters and that form the separation of the basins or tributary hydrographic regions of the Atlantic to the east and the Pacific to the west. The Argentine expert Norberto Quirno Costa (Pico's replacement) replied that they had no authority to define the meaning of the main chain of the Andes as they were only demarcators.[13]

In April 1896, the agreement to facilitate territorial delimitation operations was signed, which appointed the British monarch to arbitrate in case of disagreements. In the minutes of 1 October 1898, signed by Diego Barros Arana and Francisco Moreno (Quirno Costa's replacement, who resigned in September 1896) and by his assistants Clemente Onelli (from Argentina) y Alejandro Bertrand (from Chile), the experts:

agree with the points and stretches indicated [...] 331 and 332 [...], resolv[ing] to accept them as forming part of the dividing line [...] between the Republic of Argentina and the Republic of Chile [...].

On the attached map, point 331 is Fitz Roy and 332 is Mount Stokes, both being agreed as boundary markers, although the former is not on the watershed and was taken as a natural landmark. As the experts did not access the area, they established the caveat that if the geographical principle did not run where they had supposed it did, there could be modifications.[14]

When the experts could not agree on different stretches of the border, it was decided in 1898 to resort to Article VI paragraph 2 of the 1881 Boundary Treaty and request Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom for an arbitration ruling on the issue, who appointed three British judges. In 1901, one of the judges, Colonel Thomas Holdich, traveled to study the disputed areas.[17]

The Argentine government argued that the boundary should essentially be an orographic boundary along the highest peaks of the Andes and the Chilean government argued for a continental watershed. The tribunal considered that the language of the 1881 treaty[18] and the 1893 protocol was ambiguous and susceptible to various interpretations, the two positions being irreconcilable. On 20 May 1902, King Edward VII issued the sentence which divided the territories of the four disputed sections within the boundaries defined by the extreme claims on both sides and appointed a British officer to demarcate each section in mid-1903. The award did not issue on the ice field, for, in its article III, it sentenced:

The award thus considered that in that area the high peaks are water dividing and therefore there was no dispute. Both experts, Francisco Moreno from Argentina and Diego Barros Arana from Chile agreed on the border between Fitz Roy and Stokes.[20] Since 1898, the demarcation of the border in the ice field, between the two mountains, was defined on the next mountains and their natural continuity: Fitz Roy, Torre, Huemul, Campana, Agassiz, Heim, Mayo, and Stokes.[7][8][9] In 1914, the Mariano Moreno range was visited by an expedition; however, Francisco Moreno already knew of its existence.[21]From Mount Fitz Roy to Mount Stokes the boundary line has already been determined.[19]

Puna de Atacama dispute (1889-1898)

editThe Puna de Atacama dispute, sometimes referred to as Puna de Atacama Lawsuit (Spanish: Litigio de la Puna de Atacama), was a border dispute involving Argentina, Chile and Bolivia in the 19th century over the arid high plateau of Puna de Atacama located about 4500 meters above the sea around the current borders of the three countries.[22]

The dispute originated with the Chilean annexation of the Bolivian Litoral Department in 1879 during the War of the Pacific. That year, the Chilean Army occupied San Pedro de Atacama, the main settlement of the current Chilean part of Puna de Atacama. By 1884, Bolivia and its ally Peru had lost the war, and Argentina communicated to the Chilean government that the border line in the Puna was still a pending issue between Argentina and Bolivia. Chile answered that the Puna de Atacama still belonged to Bolivia. The same year, Argentina occupied Pastos Grandes in the Puna.

Bolivia had still not signed any peace treaty with Chile until the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1904. In the light that influential Bolivian politicians considered the Litoral Province to be lost forever, the adjacent Puna de Atacama appeared to be a remote, mountainous and arid place that was difficult to defend. That prompted the Bolivian government to use it as a tool for to obtaining benefits from both Chile and Argentina. That led to the signature of two contradictory treaties in which Bolivia granted Argentina and Chile overlapping areas:

- On May 10, 1889, a secret treaty between the Argentine minister Norberto Quirno Costa and the Bolivian envoy Santiago Vaca Guzmán was signed in Buenos Aires. The treaty established that Argentina renounced to its claims on Tarija in exchange of all the Bolivian Puna de Atacama.

- On May 19, 1891, the Matta-Reyes Protocol was signed between Chile and Bolivia. It recognised the Bolivian territories occupied by Chile since the War of the Pacific as ceded to Chile, including those in the Puna de Atacama, in exchange of defaulting some debts.

On November 2, 1898, Argentina and Chile signed two documents in which they decided to convene a conference to define the border in Buenos Aires with delegates of both countries.[23] If there was no agreement, a Chilean and Argentine delegate and the United States minister to Argentina, William Buchanan, would decide. As foreseen, there was no accord at the conference, and Buchanan proceeded with the delegates of Chile, Enrique Mac Iver, and Argentina José Evaristo Uriburu, to define the border.

Of the 75,000 km2 in dispute, 64,000 (85%) were awarded to Argentina and 11,000 (15%) to Chile.[23]Arms race and foreign policy cooperation

editDreadnought race

editAt the start of the 1900s a naval arms race began amongst the most powerful and wealthy countries in South America: Argentina, Brazil and Chile. It began when the Brazilian government ordered three formidable battleships whose capabilities far outstripped older vessels after the Brazilian Navy found itself well behind the Argentine and Chilean navies in quality and total tonnage.

Baltimore Crisis

editDuring the Baltimore Crisis which brought Chile and the United States to the brink of war in 1891 (at the end of the 1891 Chilean Civil War), the Argentine foreign minister Estanislao Zeballos offered the US-minister in Buenos Aires the Argentine province of Salta as base of operations from which to attack Chile overland.[24]: 65 In return, Argentina asked the U.S. for the cession of southern Chile to Argentina.[25] Later, Chile and the United States averted the war.

Pactos de Mayo and 1902 Andes Boundary Case

editThe Pactos de Mayo are four protocols signed in Santiago de Chile by Chile and Argentina on 28 May 1902 in order to extend their relations and resolve its territorial disputes. The disputes had led both countries to increase their military budgets and run an arms race in the 1890s. More significantly the two countries divided their influence in South America into two spheres: Argentina would not threaten Chile's Pacific Coast hegemony, and Santiago promised not to intrude east of the Andes.[24]: page 71

The 1902 Arbitral award of the Andes between Argentina and Chile (Spanish: Laudo limítrofe entre Argentina y Chile de 1902) was a British arbitration in 1902 that established the present-day boundaries between Argentina and Chile. In northern and central Patagonia, the borders were established between the latitudes of 40° and 52° S as an interpretation of the Boundary treaty of 1881 between Chile and Argentina.

As result of the arbitration, some Patagonian lakes, such as O'Higgins/San Martín Lake, became divided by a national boundary. Additionally the preferences of settled colonists in a cultivated part of the area in dispute had been canvassed. The boundary proposed in the arbitration was a compromise between the boundary preferences of the two disputing governments, which strictly followed neither the alignment of highest peaks nor the fluvial watershed, and was published in the name of King Edward VII.Snipe incident

editIn 1958 the Argentine Navy shelled a Chilean lighthouse and disembarked infantry in the uninhabitable islet Snipe, at the east entrance of the Beagle Channel.

Laguna del Desierto dispute (1949-1994) and the killing of Hernán Merino Correa

editThe Laguna del Desierto incident, in Argentina called also Battle of Laguna del Desierto occurred between four members of Carabineros de Chile and 90 members of the Argentine Gendarmerie and took place in zone south of O'Higgins/San Martín Lake on 6 November 1965, resulting in Lieutenant Hernán Merino Correa killed and Sergeant Miguel Manríquez injured, both members of Carabineros, creating a tense atmosphere between Chile and Argentina.

Encuentro River-Alto Palena boundary dispute (1913-1966)

editThe Encuentro River-Alto Palena boundary dispute was a territorial dispute between the Republic of Argentina and the Republic of Chile over the delimitation of the boundary between milestones XVI and XVII of their common border in the valleys located north of Lake General Vintter/Palena (formerly Lake General Paz), which was resolved on November 24, 1966 by means of an arbitration decision of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom.

The ruling divided the disputed territory between the two countries, which was distributed between the commune of Palena in the province of Palena, Región de Los Lagos in Chile and the department of Languiñeo in the province of Chubut in Argentina.[26]

Beagle conflict (1904-1984) and the Argentinian invasion plan "Operation Soberanía"

editTrouble once again began to brew in the 1960s, when Argentina began to claim that the Picton, Lennox and Nueva islands in the Beagle Channel were rightfully theirs, although this was in direct contradiction of the 1881 treaty, as the Beagle Channel Arbitration, and the initial Beagle Channel cartography since 1881 stated.

Both countries submitted the controversy to binding arbitration by the international tribunal. The decision (see Beagle Channel Arbitration between the Republic of Argentina and the Republic of Chile, Report and Decision of the Court of Arbitration) recognized all the islands to be Chilean territory. Argentina unilaterally repudiated the decision of the tribunal and planned a war of aggression against Chile.[27]

Direct negotiations between Chile and Argentina in 1977-78 failed and relations became extremely tense. Argentina sent troops to the border in Patagonia and in Chile large areas were mined. On 22 December, Argentina started Operation Soberanía in order to invade the islands and continental Chile, but after a few hours stopped the operation when Pope John Paul II sent a personal message to both presidents urging a peaceful solution. Both countries agreed that the Pope would mediate the dispute through the offices of Cardinal Antonio Samoré his special envoy (See Papal mediation in the Beagle conflict).

On 9 January 1979 the Act of Montevideo was signed in Uruguay pledging both sides to a peaceful solution and a return to the military situation of early 1977. The conflict was still latent during the Falklands War and was resolved only after the fall of the Argentine military junta.

A number of prominent public officials in Chile still point to past Argentine treaty repudiations when referring to relations between the two neighbors.[28][29][30][31][32][33]

Falklands War

editDuring the Falklands War in 1982, with the Beagle conflict still pending, Chile and Colombia were the only South American countries to abstain from voting in the TIAR.

The Argentine government planned to seize the disputed Beagle Channel islands after the occupation of the Falkland Islands. Basilio Lami Dozo the then Chief of the Argentine Air Force, disclosed that Leopoldo Galtieri told him that:

- "[Chile] have to know what we are doing now, because they will be the next in turn.[34]

Óscar Camilión, the last Argentine Foreign Minister before the war (29 March 1981 to 11 December 1981) has stated that:

- "The military planning was, after the solution of the Falklands case, to invade the disputed islands in the Beagle. That was the determination of the Argentine Navy."[35]

These preparations were public. On 2 June 1982 the newspaper La Prensa published an article by Manfred Schönfeld explaining what would follow Argentina's expected victory in the Falkland Islands:

- "The war will not be finished for us, because after the defeat of our enemies in the Falklands, they must be blown away from South Georgia, the South Sandwich Islands, and all Argentine Austral archipelagos."[36]

Argentine General Osiris Villegas demanded (in April 1982) after the successful Argentine landing in the Falklands that his government stop negotiations with Chile and seize the islands south of the Beagle. In his book La propuesta pontificia y el espacio nacional comprometido, (p. 2), he asked:

- no persistir en una diplomacia bilateral que durante años la ha inhibido para efectuar actos de posesión efectiva en las islas en litigio que son los hechos reales que garantizan el establecimiento de una soberanía usurpada y la preservación de la integridad del territorio nacional.[37]

This intention was probably known to the Chilean government,[38] as the Chileans provided the United Kingdom with 'limited, but significant information' during the conflict. The Chilean Connection is described in detail by Sir Lawrence Freedman in his book The Official History of the Falklands Campaign.

Post-Pinochet democratic governments in Chile have given greater support to the Argentine claim on the Falkland Islands.[39][40][41][42]

In June 2010 (as in 2009[43] and years before[44][45][46][40]) Chile has supported the Argentine position at the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization calling for direct negotiations between Argentina and the United Kingdom concerning the Falkland Islands dispute.[47]

Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1984

editThis important treaty (Spanish: Tratado de Paz y Amistad de 1984 entre Chile y Argentina) was an agreement signed in 1984 between Argentina and Chile establishing friendly relations between the two countries. Particularly, the treaty defines the border delineation and freedom of navigation in the Strait of Magellan and gives possession of the Picton, Lennox and Nueva islands and sea located south of Tierra del Fuego to Chile, but the most part of the Exclusive Economic Zone eastwards of the Cape Horn-Meridian to Argentina. After that, other border disputes were resolved by peaceful means.

The 1984 treaty was succeeded by the Maipu Treaty of Integration and Cooperation (Tratado de Maipú de Integración y Cooperación) signed on 30 October 2009[48]

Post-1990 relations

editArgentine support for Bolivia

editDespite the Pactos de Mayo agreement, in 2004 Argentina proposed to establish a "corridor" through Chilean territory under partial Argentine administration as a Bolivian outlet to sea. After talks with Chilean ambassador to Argentina, the Kirchner government pulled out of the proposal and declared the issue as "concerning Chile and Bolivia" only.[49][50]

Border issues

editIn 1898 the border in the Southern Patagonian Ice Field was defined and wasn't objected during the 1902 Arbitral award of the Andes which defined most of the border on the current Province territory. Both experts, Francisco Pascasio Moreno from Argentina and Diego Barros Arana from Chile agreed on the border between Mount Fitz Roy and Cerro Daudet.[51] However the border started being questioned by Argentina later on which started the dispute between both countries.

In the 1990s, relations improved dramatically. The dictator and last president of the Argentine Military Junta, General Reynaldo Bignone, called for democratic elections in 1983, and Augusto Pinochet of Chile did the same in 1989. As a consequence, militaristic tendencies faded in Argentina. The Argentine presidents Carlos Menem and Fernando de la Rúa had particularly good relations with Chile. In a bilateral manner, both countries settled all the remaining disputes except Laguna del Desierto, which was decided by International Arbitration in 1994. That decision favoured Argentine claims.[52][53][54][55][56]

According to a 1998 negotiation held in Buenos Aires, a 50 km (31 mi) a border redraw is agreed, being pending to this day the part between Mount Fitz Roy and Cerro Murallón,[57] however a new border was drawn between Cerro Murallón and Cerro Daudet.

In 2006, president Néstor Kirchner invited Chile to define the border in the pending area, but Michelle Bachelet's government left the invitation unanswered.[58] The same year, the Chilean government sent a note to Argentina complaining that Argentine tourism maps showed the boundary claimed by Argentina in the Southern Patagonian Ice Field prior to the 1998 agreement, placing most of the area in Argentina.

In the maps published in Argentina, until today, the region continues to be shown without the white rectangle, as can be seen in a map of Santa Cruz on a website of an official Argentine agency.[59] While in the official Chilean maps and most tourist maps, the rectangle is shown and it is clarified that the boundary is not demarcated according to the 1998 treaty.[60][61][62]

Officially Chile is a neutral party in the Argentine claim on the Falkland Islands. Although Chile acknowledges the Argentine claim as legal, it does not support any special party continuously calling for peaceful negotiations to resolve the matter.[63]

Geopolitics over Antarctica and the control of the passages between the south Atlantic and the south Pacific have led to the founding of cities and towns such as Ushuaia and Puerto Williams, both of which claim to be the southernmost cities in World. Currently, both countries have research stations in Antarctica, as does the United Kingdom. All three nations claim the totality of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Dispute over the extended continental shelf

editThe United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of April 30, 1982, which entered into force on November 16, 1994, established the regime of the continental shelf in Part VI (Articles 76 to 85), defining in Article 76, paragraph 1 what is understood as a continental shelf.

Argentina ratified the convention on January 12, 1995, and it came into force for the country on December 31, 1995.

On August 25, 1997, Chile signed and ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and it entered into force for the country on September 24, 1997.[64]

In 2009, Argentina submitted a presentation to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, which was accepted in 2016 by the UNCLOS.[65] The map in the submission included the disputed territories with the United Kingdom, such as the Falkland Islands, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands, a crescent-shaped area south of Argentina's territorial sea as defined in the 1984 treaty with Chile.[66] This area was also claimed by Chile as part of its presential sea,[67] and the sea surrounding the Antarctic Peninsula, which is claimed by all three aforementioned countries.[68] That same year, on May 8, Chile submitted its Preliminary Report to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.[69][70][71]

In 2020, the Argentine Chamber of Deputies unanimously approved the outer limit of the Argentine Continental Shelf in Law 27,557.[72]

That same year, on December 21, Chile submitted to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf the partial report on the extended continental shelf in Easter Island and Salas y Gómez.[73][74]

In 2021, Chilean President Sebastián Piñera signed Supreme Decree No. 95, which outlined the continental shelf east of the 67º 16' 0 meridian as part of Chile's continental shelf (not the extended one) area projected from the Diego Ramírez Islands, also claiming the crescent area that Argentina considers part of its extension achieved under the extended continental shelf principle.[75][76][77] This was reflected in the SHOA Chart No. 8[78] and prompted a response from the Argentine Foreign Ministry against Chile's measure.[79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86]

In February 2022, Chile submitted its second partial presentation regarding the Western Continental Shelf of the Chilean Antarctic Territory.[87][88] In August of the same year, Chile made the oral presentations of both partial submissions during the 55th Session of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf at the United Nations in New York.[89][64]

In 2023, Chile, through SHOA, made available an illustrative graphic showing all the maritime areas claimed by the country, which was once again rejected by Argentina.[90][91][92][93]

In July 2023, the International Court of Justice ruled on the priority of a Continental Shelf over a Extended Continental Shelf in the case of the territorial and maritime dispute between Colombia and Nicaragua.[94]Economy and energy

editTrade between the two countries is made mostly over the mountain passes that have enough infrastructure for large scale trade. The trade balance shows a great deal of asymmetry. As of 2005[update], Chile is the third export trading partner for Argentina, behind Brazil and the United States.[95] Significant import products from Argentina to Chile include cereal grains and meat. Recently, significant Chilean capital has been invested in Argentina, especially in the retail market sector.

In 1996, Chile became an associate member of Mercosur, a regional trade agreement that Argentina and Brazil created in the 1990s. This associate membership does not convey full membership to Chile, however. In 2009, approvals were granted for a $3-billion Pascua Lama project to mine an ore body on the border of the two countries.[96] In 2016, Argentina's exports to Chile amounted to US$2.3 billion, while Chile's exports to Argentina amounted to US$689.5 million.[97]

Gas

editArgentine president Carlos Menem signed a natural gas exportation treaty with Chilean president Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle in 1996. In 2005, President Néstor Kirchner broke the treaty due to a supply shortage experienced by Argentina. The situation in Argentina was partly resolved when Argentina increased its own imports from Bolivia, a country with no diplomatic relations with Chile since 1978. In the import contract signed with Bolivia it was specified that not even a drop of Bolivian gas could be sold to Chile from Argentina.[98]

Sports

editIn 2003, Argentine AFA's president suggested that both countries launch a joint bid for the 2014 FIFA World Cup but was abandoned in favor of a CONMEBOL unified posture to allow the tournament be hosted in Brazil.

Beginning in 2009, the Dakar Rally began to be held in South America, and both Argentina and Chile have collaborated in organizing the annual cross-border event multiple times.

Host country Chile and Argentina contested the 2015 Copa America final and Chile was declared Champion after penalty shots. Copa America 2016 trophy was also for Chile against Argentina once again in the penalty shots.[99][100]

Argentina's and Chile's clash in Pool D of the 2023 Rugby World Cup in France marked the first ever encounter between two South American teams since the inception of the tournament in 1987. Los Pumas went on to defeat Los Cóndores 59 points to 5. The encounter is considered a milestone in the development of rugby in South America.[101]

Technology

editArgentina announced on 28 August 2009[102] the election of the Japanese/Brazilian ISDB-T digital television standard with Chile following the same direction on 14 September.[103][dubious – discuss]

Military integration

editSince the 1990s, both militaries have begun a close defense cooperation and friendship policy. In September 1991 they signed together with Brazil, the Mendoza Declaration, which commits signatories not to use, develop, produce, acquire, stock, or transfer —directly or indirectly— chemical or biological weapons.

Joint exercises were established on an annual basis in the three armed forces alternately in Argentina and Chile territory. An example of such maneuvers is the Patrulla Antártica Naval Combinada (English: Joint Antarctic Naval Patrol) performed by both Navies to guarantee safety to all touristic and scientific ships that are in transit within the Antarctic Peninsula.

Both nations are highly involved in UN peacekeeping missions. UNFICYP in Cyprus was a precedent where Chilean troops are embedded in the Argentine contingent.[104] They played a key role together at MINUSTAH in Haiti(Video Haiti) and in 2005 they began the formation of a joint force for future United Nations mandates.[105] Named Cruz del Sur (English: Crux), the new force began assembly in 2008 with headquarters alternately on each country every year.[106]

In 2005, while the Argentine Navy school ship ARA Libertad was under overhaul, Argentine cadets were invited to complete their graduation on the Chilean Navy school ship Esmeralda[107] and in another gesture of confidence, on 24 June 2007, a Gendarmeria Nacional Argentina (Border Guard) patrol was given permission to enter Chile to rescue tourists after their bus became trapped in snow.[108]

Chilean earthquake

editOn 13 March 2010, following the Chilean earthquake the benefit concert Argentina Abraza Chile (English: Argentina Hugs Chile) was hosted in Buenos Aires, and an Argentine Air Force Mobile Field Hospital was deployed to Curicó.

On 8 April 2010 the newly elected Chilean president Sebastián Piñera made his first trip abroad a visit to Buenos Aires where he thanked president Cristina Fernández for the help received. He also stated his commitment to an increased cooperation between the two countries.[109]

Argentina protects fugitive of Chilean justice

editIn September 2010, CONARE (the Argentine National Refugee Commission, a department of the Argentine Interior Ministry[110]) granted asylum to Chilean citizen Galvarino Apablaza. Apablaza now lives in Argentina where he is married to journalist Paula Chain, and is father to three Argentine-born children. Chain has worked for the Argentine Government press office since 2009.[111] Apablaza is accused by Chile of being involved in the murder of Chilean Senator Jaime Guzmán in 1991, during the government of Patricio Aylwin, as well as the kidnapping of the son of one of the owners of the El Mercurio newspaper. The asylum status has been universally rejected by the Chilean government,[112] as well as by the Argentine political opposition.[113] Some Argentine media and journalists[114] have pointed out that the Argentine government ignored a ruling of the Argentine Supreme Court of Justice allowing the extradition of Apablaza.[112] Chilean state attorney Gustavo Gené has pointed out that there was no question of the Chilean legal system's authority or grounds by the Argentine Commission, and that the reasons for granting political asylum were based exclusively on "humanitarian grounds".[115]

The Argentine decree 256/2010 about the Strait of Magellan

editOn 17 February 2010 the Argentine executive issued the decree 256/2010[116] pertaining to authorisation requirements placed on shipping to and from Argentina but also to ships going through Argentine jurisdictional water heading for ports in the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands. This decree was implemented by disposition 14/2010[117] of the Prefectura Naval Argentina. On 19 May 2010 the United Kingdom presented a note verbale rejecting the Argentine government's decrees and stipulating that the UK considered the decrees "are not compliant with International Law including the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea ”, and with respect to the Straits of Magellan the note recalls that "the rights of international shipping to navigate these waters expeditiously and without obstacle are affirmed in the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Chile and Argentina with respect to the Straits of Magellan".[118]

Article 10 of the 1984 Treaty states "The Argentine Republic undertakes to maintain, at any time and in whatever circumstances, the right of ships of all flags to navigate expeditiously and without obstacles through its jurisdictional waters to and from the Strait of Magellan".

Resident diplomatic missions

edit- Argentina has an embassy in Santiago and consulates-general in Antofagasta, Concepción, Puerto Montt, Punta Arenas and Valparaíso.[119]

- Chile has an embassy in Buenos Aires and consulates-general in Bariloche, Córdoba, Mendoza, Neuquén, Río Gallegos, Rosario and Salta; and consulates in Bahía Blanca, Comodoro Rivadavia, Mar del Plata, Río Grande and Ushuaia.[120]

-

Embassy of Argentina in Santiago

-

Consulate-General of Argentina in Santiago

-

Consulate-General of Argentina in Valparaïso

-

Embassy of Chile in Buenos Aires

-

Consulate-General of Chile in Buenos Aires

-

Consulate-General of Chile in Comodoro Rivadavia

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ The annual register, or, A view of the history, politics, and literature for 1819, Volume 61, John Davis Batchelder Collection (Library of Congress) link, page 138

- ^ a b José María Rosa, Historia argentina: Unitarios y federales (1826–1841) at Google Books

- ^ Spain and the American Civil War: relations at mid-century, 1855–1868, p. 99, at Google Books

- ^ "The Alliance With Bolivia". South Pacific Times. 26 April 1879.

- ^ "Iberoamerica -- Bienvenido --". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Eyzaguirre, Jaime (1967). Breve historia de las fronteras de Chile (in Spanish). Editorial Universitaria.

- ^ a b Francisco Pascasio Moreno (1902). Frontera Argentino-Chilena - Volumen II (in Spanish). pp. 905–911.

- ^ a b Arbitraje de Limites entre Chile i la Republica Arjentina - Esposicion Chilena - Tomo IV (in Spanish). Paris. 1902. pp. 1469–1484.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Diego Barros Arana (1898). La Cuestion de Limites entre Chile i la Republica Arjentina (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Richard O. Perry (1980). "Argentina and Chile: The Struggle for Patagonia 1843-1881". The Americas. 36 (3). JSTOR: 347–363. doi:10.2307/981291. JSTOR 981291. S2CID 147607097. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Treaty of 1881 between Argentina and Chile

- ^ Sebastián Peredo. "Campos de Hielo Sur: Una Fuente para la Cooperación" (PDF). Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ a b Bartolomé, Gerardo M. (2008). Perito Moreno : el límite de las mentiras, 1852-1919. Ushuaia [Argentina]: Zagier & Urruty Publications. ISBN 978-9871468096.

- ^ a b "Revista EXACTA mente - Nro 8 - Panorama". 24 August 2010. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010.

- ^ Boundary Protocol between Chile and Argentina 1893

- ^ Peri Fagerstrom, René (1995). Por qué perdimos Laguna del Desierto? : --y por qué podríamos perder Campos de Hielo Sur? (1a. ed.). Santiago de Chile: Salón Tte. Hernán Merino Correa. ISBN 9567271127.

- ^ Carlos Leonardo de la Rosa (1998). Acuerdo sobre los hielos continentales: razones para su aprobación. Ediciones Jurídicas Cuyo. ISBN 9789509099678.

- ^ Robert D. Talbott (1967). "The Chilean Boundary in the Strait of Magellan". Hispanic American Historical Review. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "The Cordillera of the Andes Boundary Case (Argentina, Chile)" (PDF). Legal UN. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Cedomir Marangunic; Juan Ignacio Ipinza Mayor; Jorge Guzmán Gutiérrez (26 April 2021). "El Campo de Hielo Patagónico Sur ¿es mejor un mal arreglo que un buen juicio". Info Defensa. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ P. Moreno, Francisco (1899). "Explorations in Patagonia". The Geographical Journal. 14 (3). Royal Geographical Society: 262. doi:10.2307/1774365. JSTOR 1774365.

I have seen it descending from the west as an immense ice field, from the crest of the central chain, 3000 meters high, which the ice covers to its western slope in the Eyre Strait. To the south and north of it, other narrower glaciers can be seen at the extremity of the fjord-like bays.

- ^ Resende-Santos, Joao (2007). Neorealism, States, and the Modern Mass Army: A Neorealist Theory of the State (hardbound) (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 327. ISBN 978-0-521-86948-5.

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Historia de la relacciones exteriores de la Argentina

- ^ a b William F. Sater, Chile and the United States, Empires in Conflict, University of Georgia Press, 1990, ISBN 0-8203-1249-5

- ^ Arthur Preston Whitaker, The United States and the southern cone: Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, Harvard University Press, 1976, page 34

- ^ "RIO ENCUENTRO". Mágica Ruinas. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Clarín de Buenos Aires 20 December 1998

- ^ See notes of the Chilean Foreign Minister Jose Miguel Insulza, in La Tercera de Santiago de Chile 13 July 1998 "Enfatizó que, si bien la situación es diferente, lo que hoy está ocurriendo con el Tratado de Campo de Hielo Sur hace recordar a la opinión pública lo sucedido en 1977, durante la disputa territorial por el Canal de Beagle"[permanent dead link]

- ^ See notes of Senator (not elected but named by the Armed Forces) Jorge Martínez Bush in La Tercera de Santiago de Chile 26 July 1998 "El legislador expuso que los chilenos mantienen "muy fresca" en la memoria la situación creada cuando Argentina declaró nulo el arbitraje sobre el canal del Beagle, en 1978"

- ^ See notes of the Chilean Foreign Minister Ignacio Walker "Y está en la retina de los chilenos el laudo de Su Majestad Británica, en el Beagle, que fue declarado insanablemente nulo por la Argentina. Esa impresión todavía está instalada en la sociedad chilena." Clarin de B.A., 22 July 2005

- ^ See also "Reciprocidad en las Relaciones Chile - Argentina"[permanent dead link] of Andrés Fabio Oelckers Sainz. "También en Chile, todavía genera un gran rechazo el hecho que Argentina declarase nulo el fallo arbitral británico y además en una primera instancia postergara la firma del laudo papal por el diferendo del Beagle"

- ^ See notes of Director académico de la Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales Flacso, Francisco Rojas, in Santiago de Chile, in "Desde la Argentina, cuesta entender el nivel de desconfianza que hoy existe en Chile a propósito de la decisión que tomó en 1978 de declarar nulo el laudo arbitral" Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine La Nación de Buenos Aires 26 September 1997

- ^ See notes of Chilean Defense Minister Edmundo Pérez Yoma in "Centro Superior de Estudios de la Defensa Nacional del Reino de España" " ... Y que la Argentina estuvo a punto de llevar a cabo una invasión sobre territorio de Chile en 1978 ..." Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, appeared in Argentine newspaperEl Cronista Comercial 5 May 1997. These notes were later relativized by the Chilean Government (See "Chile desmintió a su ministro de Defensa". Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008. "El gobierno hace esfuerzos para evitar una polémica con Chile". Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008.)

- ^ Argentine newspaper Perfil Después de Malvinas, iban a atacar a Chile Archived 25 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine on 22. November 2009, retrieved 22. November 2009:

- Para colmo, Galtieri dijo en un discurso: "Que saquen el ejemplo de lo que estamos haciendo ahora porque después les toca a ellos".

- ^ Óscar Camilión, Memorias Políticas, Editorial Planeta, Buenos Aires, 1999, page 281:

- "Los planes militares eran, en la hipótesis de resolver el caso Malvinas, invadir las islas en disputa en el Beagle. Esa era la decisión de la Armada ..."

- ^ All articles of Manfred Schönfeld published by "La Prensa" from 10 January 1982 to 2 August 1982, are compiled in La Guerra Austral, Manfred Schönfeld, Desafío Editores S.A., 1982, ISBN 950-02-0500-9

- ^ cited in A treinta años de la crisis del Beagle, Desarrollo de un modelo de negociación en la resolución del conflicto by Renato Valenzuela Ugarte and Fernando García Toso, in Chilean Magazine "Política y Estrategia", nr. 115)

- ^ Spanish newspaper El País on 11. April 1982 Chile teme que Argentina pueda repetir una acción de fuerza en el canal de Beagle retrieved on 11. September 2010

- ^ President Bachelet:We not only support our sister republic's claims to the Malvinas islands but every year we present its case to the United Nations' Special Committee on Decolonization

- ^ a b "SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON DECOLONIZATION ADOPTS RESOLUTION EXPRESSING REGRET OVER DELAY IN TALKS TO RESOLVE FALKLAND ISLANDS (MALVINAS) DISPUTE". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Chilean Foreign Office: CHILE REAFIRMA SU POSICIÓN SOBRE ISLAS MALVINAS". Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- ^ Chilean Foreign Minister Soledad Alvear reaffirms support to Argentine claim Archived 16 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 2009 calling for direct negotiations over falkland Islands (malvinas)

- ^ "SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON DECOLONIZATION REITERATES CALL ON ARGENTINA, UNITED KINGDOM TO RESUME NEGOTIATIONS ON FALKLANDS/MALVINAS ISSUE". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "DECOLONIZATION COMMITTEE REQUESTS ARGENTINA, UNITED KINGDOM". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON DECOLONIZATION ADOPTS DRAFT RESOLUTION REITERATING NEED FOR PEACEFUL, NEGOTIATED SETTLEMENT OF FALKLAND (MALVINAS) QUESTION". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Special Committee on Decolonization Recommends General Assembly Reiterate Call". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Tratado de Maipu de Integración y Cooperacion entre Argentina y Chile". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Article Juan Gabriel Valdéz: "Hay resabios de rivalidades anacrónicas" in Argentina newspaper La Nación on 25 January 2004 in Spanish language, retrieved on 10 January 2012

- ^ "Abihaggle: "Es un tema bilateral"". Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Juan Ipinza (26 April 2021). "El Campo de Hielo Patagónico Sur ¿es mejor un mal arreglo que un buen juicio" (in Spanish). Infodefensa. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ René Peri Fagerström (1994). ¿La geografía derrotada?: el arbitraje de Laguna del Desierto, Campos de Hielo patagónico sur. SERSICOM F&E Ltda.

- ^ Stenger Larenas, Iván (1998). Teniente Merino: Héroe Nacional de la Soberanía. Carabineros' Printing.

- ^ René Peri Fagerström (1994). A la sombra del Monte Fitz Roy. Salón Teniente Merino.

- ^ "The Laguna del Desierto case". Jusmundi. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ "Boundary dispute between Argentina and Chile concerning the frontier line between boundary post 62 and Mount Fitzroy" (PDF). Legal UN. 21 October 1994. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Orellana, Pía (2 September 2020). "El límite en Campo de Hielo Patagónico Sur: Un problema incómodo pendiente" (in Spanish). El Líbero. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "Tras la fricción por los Hielos Continentales, la Argentina llama a Chile a demarcar los límites "lo antes posible"". 30 August 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Map of Santa Cruz in an official Argentine agency.

- ^ Karen Isabel Manzano Iturra (11 March 2015). "Geopolitical representation: Chile and Argentina in Campos de Hielo Sur". Estudios Fronterizos. 17 (33). Universidad de Concepción: 83–114. doi:10.21670/ref.2016.33.a04. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Campo de Hielo Sur [material cartográfico] Instituto Geográfico Militar". Biblioteca Nacional (Chile). Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ "Mapa Turístico de la XII Región de Magallanes y La Antártica Chilena ..:: Antes de viajar, navegue... Turismovirtual.cl ::." www.turismovirtual.cl.

- ^ [1] Archived 11 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine CHILE REAFIRMA SU POSICIÓN SOBRE ISLAS MALVINAS. La Cancillería reafirmó la política del Gobierno de Chile de respaldar los legítimos derechos de soberanía de la República Argentina en la disputa referida a la cuestión de las Islas Malvinas.

- ^ a b "Proyecto Plataforma Continental de Chile". Government of Chile. 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Argentina presents territorial claim". BBC. 21 April 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Crescent beyond point F of the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship: new maritime dispute with Argentina". El Mostrador. 23 March 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Luis Kohler Gary (March 2001). "The Presential Sea of Chile. Its current challenge" (PDF). Revista Marina.

- ^ Fulvio Rossetti (August 2021). "No man's land, everyone's land. Unity and nature in the cultural figures of the Antarctic Peninsula and surrounding areas". Revista 180. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Información Preliminar Indicativa de los límites exteriores de la Plataforma Continental y una descripción del estado de preparación y de la fecha prevista de envío de la presentación a la Comisión de Límites de la Plataforma Continental" (PDF). Government of Chile. May 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "New limits dispute arises between Chile and Argentina". Merco Press. 30 August 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "Argentina/Chile continental shelf dispute: "beware about arousing nationalism in electoral processes"". Merco Press. 7 September 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "Deputies approved two laws to strengthen sovereignty over the Malvinas" (in Spanish). Página/12. 5 August 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Chile seeks to define the Continental Shelf of the province of Easter Island". La Prensa Austral. 16 June 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "The extended continental shelf around Easter Island and Salas y Gómez". Revista Marina. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Piñera: "What Chile is doing is exercising its right and declaring its continental shelf"" (in Spanish). T13. 29 August 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Chile will ask the UN to recognize its maritime platform extension, which is already causing conflict with Argentina" (in Spanish). Infobae. 16 December 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Diplomatic conflict between Argentina and Chile over the Continental Shelf" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (Spain). 14 September 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Juan Ignacio Ipinza Mayor (3 September 2021). "Southern Patagonian Ice Field and SHOA Chart No. 8" (in Spanish). InfoGate. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "After decrees: Argentina accuses Chile of trying to "appropriate" the southern continental shelf" (in Spanish). T13. 28 August 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Argentina claims Chile over an area it does not yet own". Revista Puerto. 30 August 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Foreign Minister Allamand states that "it seems unnecessary to engage in further public debate" with Argentina over the continental shelf". Emol. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Solá rejected the document signed by the PRO on the continental shelf: "They deny our rights," he said". Realidad Sanmartinense. 31 August 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Chile vs. Argentina por la plataforma continental en el Mar Austral: perspectivas". La Capital de Mar del Plata. 5 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Plataforma continental chilena en el mar de la zona austral, un interés esencial del Estado". CEP Chile. 28 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Chile and Argentina agree to discuss ongoing continental shelf differences south of Cape Horn". Merco Press. 30 August 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ 7 September 2021. "Argentina sends Chile diplomatic note rejecting their "expansive vocation"". Merco Press. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Plataforma Continental Occidental del Territorio Chileno Antártico" (PDF). National Committee for the Continental Shelf - Chile. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Chile to present the extended continental shelf west of Antarctica to the UN". Info Defensa. 16 December 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Chile realiza sus presentaciones orales de Plataforma Continental extendida de Isla de Pascua y Antártica a la Comisión de Límites de la Plataforma Continental en Naciones Unidas". DIFROL. 10 August 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "SHOA makes available an illustrative graphic of Chilean maritime jurisdiction areas". Armada de Chile. 23 August 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Continental shelf: The stance Chile has maintained in response to Argentina's objections and the new frustration over SHOA maps". Emol. 29 August 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Argentine Foreign Ministry sends formal complaint to Chile over Navy map including continental shelf". Emol. 29 August 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Argentina protests over map with continental shelf created by Chilean Navy". Nuevo Poder. 29 August 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Nueva controversia en el mar de la zona austral". 31 August 2024. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Argentina Exports – partners". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Francisca Pouiller. "Argentina celebrates mining day, Pascua Lama go-ahead". Mining Weekly. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Argentina | Exports and Imports | by Country 2016 | WITS | Data". Wits.worldbank.org. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "Bolivia ratifica que Argentina no puede revender gas a Chile". abc COLOR. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Clarín.com". Archived from the original on 13 June 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "Ya es oficial: el Dakar se volverá a correr en Argentina y Chile". 23 March 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Imogen, Ainsworth (30 September 2023). "Rugby World Cup 2023 - Argentina romp to emphatic victory over Chile in South American clash". Eurosport.

- ^ "Argentina: Adopta nueva norma de TV Digital" [Argentina: It adopts new norm of Digital TV] (in Spanish). 2009 CIO América Latina. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ [2] Gobierno de Chile adopta norma de Televisión Digital para el País Archived 22 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Argentine Army: UNFICYP Archived 23 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine

UN: Cyprus - UNFICYP - Facts and Figures

Chilean Army: Misión de la ONU en Chipre desde el año 2003 Archived 12 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

Brasilian Army: UNFICYP Archived 18 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine - ^ "Avance para la fuerza combinada con Chile". 5 December 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Destinan $30 millones para operar con Chile". 18 March 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Cadetes argentinos navegarán en la fragata chilena Esmeralda". 28 August 2004. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Rescatan a 50 pasajeros que quedaron varados por la nieve en el norte chileno" Clarin newspaper: (Spanish)

- ^ Piñera: "Lo mejor de la relación entre la Argentina y Chile está por venir" Archived 11 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Argentina: se conforma Comisión para determinar la condición de refugiado y facilitar su integración (in Spanish)

- ^ "Las razones que expondrá Cristina para darle refugio al ex guerrillero". Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ a b "El Gobierno da refugio al ex terrorista Apablaza". 1 October 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "La UCR pidió la "inmediata" extradición de Apablaza". 20 September 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Lanata Galvarino Apablaza DDT. 6 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Grupo Copesa (1 October 2010). "Gustavo Gené: 'No hay ningún cuestionamiento al sistema jurídico chileno' - Política - LA TERCERA". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Argentine executive (2010), Decreto 256/2010, Buenos Aires: Argentina, archived from the original on 23 February 2010, retrieved 12 April 2010

- ^ Prefectura Naval Argentina (2012), B.O. 26/04/10 - Disposición 14/2010-PNA - TRANSPORTE MARITIMO, Argentina: Prefectura Naval, archived from the original on 15 October 2012, retrieved 12 April 2013

- ^ Mercopress (2010), UK rejects Argentine decision regarding Falklands' shipping, South Atlantic News Agency, archived from the original on 25 August 2010, retrieved 12 April 2013

- ^ Embajada Argentina en Santiago de Chile

- ^ Embajada de Chile en Buenos Aires

Sources

edit- (in Spanish) Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas Archived 18 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine by Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros

- (in Spanish) Combined Military Force Cruz del Sur - official press release