Marathon Man is a 1974 conspiracy thriller novel by William Goldman. It was Goldman's most successful thriller novel, and his second suspense novel.[2]

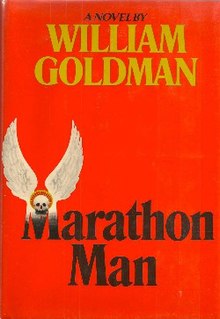

First edition | |

| Author | William Goldman |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Paul Bacon[1] |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Conspiracy thriller |

| Publisher | Delacorte Press |

Publication date | 1974 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 309 pp |

| ISBN | 0-440-05327-7 |

| OCLC | 940709 |

| 813/.5/4 | |

| LC Class | PZ4.G635 Mar PS3557.O384 |

| Followed by | Brothers |

In 1976 it was made into a film of the same name, with a screenplay by Goldman, starring Dustin Hoffman, Laurence Olivier, and Roy Scheider and directed by John Schlesinger.

Plot synopsis

editA former Nazi SS dentist at Auschwitz, Dr. Christian Szell, now residing in Paraguay, has been living on the proceeds of diamonds he extorted from prisoners in the concentration camp. The diamonds are kept at a bank in New York City by his father. The sales and transfers of proceeds are facilitated by a secret US agency called The Division for whom Szell has provided information about other escaped Nazis. When his father dies in a car accident, Szell must come to New York himself to retrieve the diamonds, as there is no one else he can trust.

Meanwhile, at Columbia University, Thomas Babington "Tom" Levy,[3] known by his brother as "Babe" (the first and middle names are a reference to Thomas Babington Macaulay,[4] and the nickname is a reference to Babe Ruth) is a postgraduate student in history and an aspiring marathon runner. He is haunted by the suicide of his brilliant academic father, H. V. Levy, who was one of the victims of McCarthyism, when Babe was ten. Babe's PhD dissertation aims to clear his father's name of alleged Communist affiliations. Unbeknownst to Babe, his elder brother by ten years (and best friend), Henry David "Hank" Levy (after Henry David Thoreau), known by Babe as "Doc", works in The Division under the name "Scylla" and has been helping to move Szell's diamonds as part of his duties.

Szell arrives in New York City and meets with Doc. Suspecting Doc of planning to rob him when he retrieves the diamonds, Szell stabs him and leaves him for dead. Mortally wounded, Doc makes his way to Babe's apartment and dies in his brother's arms. When Szell learns this, he believes Doc may have told Babe about the plan to rob him. Szell's two henchmen abduct Babe. Szell tortures Babe by drilling into his teeth without anesthetic and repeatedly asking the question, "Is it safe?", referring to Szell's appointment to collect his diamonds from the bank. Babe does not know what the question means nor the interrogator's identity until Szell explains after torturing him.

When Szell finally concludes Babe knows nothing, he orders his people to dispose of the young man. Though in great pain, Babe escapes and, thanks to his training as a marathoner, outruns his pursuers.

Seeking revenge for the killing of Doc, Babe arranges a rendezvous at which Szell's people, who hope to eliminate him, are killed instead. He then intercepts Szell at his bank, a confrontation that ultimately leads to Szell's death.

Background

editGoldman says he was inspired by the idea of bringing a major Nazi to the biggest Jewish city in the world. He wrote the book after the death of his beloved editor Hiram Haydn, who had edited all of his books from 1960 to 1974, and feels he never would have written something as commercial as Marathon Man had Haydn been alive.[5]

Goldman later expressed dissatisfaction with the novel, but it went on to be his most successful book to that date.[5]

Development

editGoldman wrote the novel in 1973 while living on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.[6] His concept began with the antagonist. Initially he wanted to write a story about Josef Mengele needing to travel to the United States for medical care, but he realized that he did not want to write a villain character who had frail health. After reading articles about Nazis stealing golden teeth from prisoners and accumulating wealth, Goldman created a villain who came to the United States to get his diamonds. He named the character after George Szell, a conductor. Goldman made Szell a dentist after considering memories of negative dental experiences as a child.[7] Because Goldman was an American, he chose New York City as the setting of his work.[8]

He decided to make the hero "a total innocent" who would be "as virginal as [he] could".[8] Goldman's concept behind Babe was "what if someone close to you was something totally different from what you thought?"[8] This refers to Babe's relationship with Doc/Scylla.[8] He wanted Babe to be weaker than Szell. Goldman created a weaker hero because "If the worst guy in the world gets in the ring with the toughest guy in the world, that's Stallone territory, and I can't write that. I don't mean I am pristine and above it all—obviously I could write it—anyone can write it—because anyone can write anything badly."[8]

Goldman stated that once he had the basic concept behind the story, he was "essentially mixing and matching, figuring out the surprises, hoping they would work".[8] Goldman developed the idea of Babe having a toothache and Szell drilling into that tooth. When he discussed the scene with a periodontist, the periodontist told him that it would be more painful if the torturer drilled into a healthy tooth.[8]

Goldman says he wrote at least two versions of the novel.[9]

Publication

editEvarts Ziegler, Goldman's agent, later recalled "going in we felt we had a home run in both fields, book and movie." They signed with Delacorte because Goldman wanted to control hard and soft cover rights. The deal amounted to $2 million for three books (Marathon Man, Magic, and Tinsel). The film rights to Marathon Man were sold for $450,000.[10]

Adaptations

editBBC Radio 4 aired a radio adaptation of the novel.[11]

A film adaptation starring Dustin Hoffman as Babe, Roy Scheider as Doc and Laurence Olivier as Szell was released in 1976.

Sequel

editThe novel led to a sequel, Brothers (1986).

Notes

edit- ^ Modern first editions – a set on Flickr

- ^ D'Ammassa, Don. Encyclopedia of Adventure Fiction. Infobase Publishing, 2009. 139. Retrieved from Google Books on January 31, 2012. ISBN 0-8160-7573-5, ISBN 978-0-8160-7573-7.

- ^ Goldman, William. Marathon Man. Random House Digital, Inc., Jul 3, 2001. p. 237. Retrieved from Google Books on January 9, 2012. ISBN 0-345-43972-4, ISBN 978-0-345-43972-7. '"Here lies Thomas Babington Levy, 1948–1973, Caught by a Cripple."'

- ^ Goldman, William. Marathon Man. Random House Digital, Inc., Jul 3, 2001. 224. Retrieved from Google Books on January 9, 2012. ISBN 0-345-43972-4, ISBN 978-0-345-43972-7. "After, of course, the great British historian."

- ^ a b Richard Andersen (1979). William Goldman. Twayne Publishers. p. 94.

- ^ Goldman, William Goldman: Four Screenplays with Essays. p. 145.

- ^ Goldman, William Goldman: Four Screenplays with Essays. p. 143.

- ^ a b c d e f g Goldman, William Goldman: Four Screenplays with Essays. p. 144.

- ^ Goldman, W. (Jun 15, 1983). "Ailing laurence olivier proves to be a 'marathon' man". Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 175925022.

- ^ Rosenfield, Paul (Feb 18, 1979). "WESTWARD THEY COME, BIG BUCKS FOR BIG BOOKS". Los Angeles Times. p. n1, 32–33, and 35–36. - Clippings of first, second, third, fourth, and fifth pages from Newspapers.com. Cited: page N33

- ^ Quirke, Antonia (2017-07-20). "Marathon Man and a marvellously gruesome dentist's drill". New Statesman. Retrieved 2019-01-05.

References

edit- Goldman, William. William Goldman: Four Screenplays with Essays. Hal Leonard Corporation, 1995. ISBN 155783198X, 9781557831989.

External links

edit- "Marathon Man Supplemental Liner Notes." (Archive) Film Score Monthly CD (FSMCD). Volume 13, No. 5. HTML format