Circassian nationalism[1][2][a] is the desire among Circassians worldwide to preserve their genes, heritage and culture,[3][4][5] save their language from extinction,[2][6][7] raise awareness about the Circassian genocide,[8][9][10] return to Circassia[11][12][13][14] and establish a completely autonomous or independent Circassian state in its pre-Russian invasion borders.[13][14][15]

In almost every community of Circassians around the world, a local advisory council called the "Adyghe Khase" can be found.[16] The goal of such councils are to provide Circassians with a comfortable place where they can speak Circassian, engage in Circassian cultural activities, learn about the laws of Adyghe Xabze or seek advice. These advisory councils are coordinated on a local and regional basis, and communicate internationally through the International Circassian Association (ICA).[17]

Russo-Circassian War

editCircassia and the Circassians before the Russian invasion

editThe Circassians have inhabited historical Circassia since antiquity.[18] They formed many states throughout time that were known to the outside world, occasionally falling under brief control of the Romans, and later Scythian and Sarmatian groups, followed by Turkic groups, most importantly the Khazars, and then becoming a protectorate of the Ottoman Empire. Nonetheless, the Circassians generally maintained a high level of autonomy. Due to their Black Sea coast location, owning the important ports of Anapa, Sochi and Tuapse, they were heavily involved in trade, and many early European slaves were Circassians (additionally, the Mamluks of Egypt, the Persian ghulams, and the Ottoman Janissaries had a strong ethnic Circassian component, and the Circassian Mamluks even ruled Egypt).

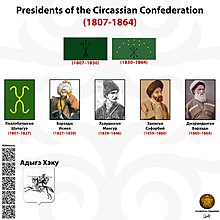

Ruling themselves, Circassians have interchangeably used feudal systems, tribal-based confederacies, tribal republics, and monarchies to rule their lands, often incorporating a mix of two or all four. Circassia was generally organized by tribe, with each tribe having a set territory, roughly functioning as greater than a province, but less than completely autonomous, comparable to a US state (the level of autonomy varied between tribes and time). Not all of the tribes within the confederation were ethnic Circassian: at different times, Nogais, Ossetians, Balkars, Karachays, Ingush, and even Chechens participated as members of the confederation. In the 19th century, three tribes, Natukhaj, Shapsug and Abdzakh, overthrew their feudal governments in favor of direct democracy;[19][20] however, this was cut short by the conquering of Circassia by Tsarist Russia and the end of independence after the Russo-Circassian War.

Russian invasion, conflict and the genocide

editThe earliest date of Russian expansion into Circassian land was in the 16th century, under Ivan the Terrible, who notably married a Kabardin wife Maria Temryukovna, the daughter of Muslim prince Temryuk of Kabardia to seal a contract of alliance with the Kabardins, a subdivision of the Circassians. After Ivan's death, however, Russian interest in the Caucasus subsided and they remained largely removed from its affairs; with other states in between Russia and Circassia, notably the Crimean Khanate and the Nogai Horde.[21] The Circassians freely roamed in their native regions for centuries afterwards, but during the peaks of the Persian Safavids and Afsharids, parts of the Circassian lands fell under Persian rule for a brief number of years.

In the 18th century, however, Russia regained its imperial ambitions in the region, and expanded steadily southward, with the eventual goal of obtaining the riches of the Middle East and Persia, using the Caucasus as a connection to the region.[22] The first incursion of the Russian military into Circassia occurred in 1763, as part of the Russo-Persian War.

Eventually, due to a perceived need for Circassian ports and a view that an independent Circassia would impede their plans to extend into the Middle East, Russia soon moved to annex Circassia. Tensions culminated in the devastating Russo-Circassian War, which in its later stages was eclipsed by the Crimean War. Despite the fact that a similar war was going on at the other side of the Caucasus (Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Dagestan fighting against Russia to preserve their states' existence), as well as the attempts of some (ranging from Circassian princes to Imam Shamil to Britain) to connect the two struggles, connections between the Circassians and their allies with their Eastern Caucasian counterparts were quashed by Ossetian and Karachay-Balkar alliances with Russia.

Hostilities peaked in the 19th century, and led directly to the Russo-Circassian War, in which the Circassians, along with the Abkhaz, Ubykhs, Abazins, Nogais, Chechens and in the later stages the Ingush (who started out as allies of Russia), as well as a number of Turkic tribes, fought the Russians to maintain their independence. This conflict became entangled with the ensuing Crimean War, and at various times the Ottomans gave little assistance to the Circassian side. Additionally, the Circassians succeeded in securing the sympathies of London, and in the later stages of the Crimean War, the British supplied arms and intelligence to the Circassians, who reciprocated by busying the Russians and returning with intelligence of their own. However, this was not enough to save the Circassians from the oncoming defeat and Russian domination. Russia finally subdued the Circassians, tribe after tribe, with the Ubykhs, Abazins and Abkhaz being last.

Russia soon proceeded to order the Muhajirs. Approximately 1-1.5 million Circassians were killed, not discriminating between women, elderly or children and upon order of the Tsar, most of the Muslim population was deported, mainly to the Ottoman Empire, causing the exile of another 1.5 million Circassians and others. This effectively annihilated (or deported) 90% of the nation, and named as the Circassian Genocide.[23] Circassians refugees were viewed as an expedient source for military recruits,[24] and were settled in restive areas of nationalist yearnings, Armenia, the Kurdish regions, the Arab regions and the Balkans.[25] The Balkan and Middle Eastern societies they settled among considered them foreign aliens, and tensions between the Circassians and the natives over land and resources occasionally led to bloodletting, with the impoverished Circassians sometimes raiding the natives.[26] At the Conference of European Countries which was held in December 1876 – January 1877 in Istanbul, the idea of transferring the Circassians from the Balkans to the Asian states of the empire was introduced. With the beginning of the Russian-Ottoman War in 1877, Circassians abandoned their villages and set on the road with the retreating Ottoman troops.[27] Still more Circassians were forcefully assimilated by nationalist states (Turkey, Iran, Syria, Iraq) who looked upon non-Turk/Persian/Arab ethnicity as a foreign presence and a threat.

Circassian nationalism in history

editCircassians in the Ottoman Empire

editCircassians in the Ottoman Empire mainly kept to themselves and maintained their separate identity, even having their own courts, in which they would tolerate no outside influence, and various travelers noted that they never forgot their homeland, for which they continually yearned.[28]

After the Circassian genocide, Circassians who were exiled to Ottoman lands initially suffered heavy tolls. The Circassians were initially housed in schools and mosques or had to live in caves until their resettlement. The Ottoman authorities assigned lands for Circassian settlers close to regular water sources and grain fields. Numerous died in transit to their new homes from disease and poor conditions.[29]

In Romania, the Circassians were granted privileges by the Ottoman authorities because of their Muslim religion and would frequently enter in conflict with the Christian population of the region. They would give parts of their gains to the Ottoman authorities. Palace of the Pasha (now the Tulcea Art Museum) and the Azizyie Mosque of Tulcea were built with funds coming from Circassians.[30][31]

In Bulgaria, one of the major spots of arrival for the Circassians, the lives of Circassians were not easy, as diseases spread. Many families completely disappeared within a few years. Around 80,000 Circassians lived in "death camps" on the outskirts of Varna, where they were deprived of food and subjected to diseases. As a result, both the Muslim and Christian population of Vidin volunteered to support the Circassian settlers by increasing grain production for them. The Circassians were seen as a "Muslim threat" and expelled from Bulgaria and other parts of the Balkans by Russian armies following the end of the Russo-Turkish war. They were not allowed to return,[32][33] so the Ottoman authorities settled them in new other lands such as in modern Jordan, Israel, Syria and Turkey.

In Jordan, the Bedouin Arabs viewed the Circassians very negatively. The Circassians refused to pay the khuwwa ("protection" fees), and the Bedouin declared that it was halal (allowed) to murder Circassians on sight. The mutual hostility between the Circassians and their nomadic and settled Arab neighbors led to many clashes. Despite the superiority of Bedouin arms and mobility, the Circassians maintained their positions and population.[34] Later, Circassians in Jordan marked the founding of modern Amman.[35]

In Palestine-Israel, the Circassian exiles established the towns of Rehaniya and Kfar Kama.[36][37] The Bedouin Arabs viewed them as "squatters". Circassian culture occasionally clashed with Arab culture, with local Arabs looking with horror upon the equality of men and women in Circassian culture.[38] In various areas of the wider Levant region armed conflict broke out between Circassians and other local groups, especially Bedouin and Druze, with little or no Ottoman intervention; some of these feuds continued as late as the mid-20th century.[39]

In Syria, just like in Jordan and Israel, clashes occurred between the Circassian exiles and the Bedouin. They were, however, less fierce compared to the other regions and slowly cooled down.

Circassian renaissance in the Ottoman Empire

editThe next generation was quick to adapt. Circassian intellectuals took an active role in the Ottoman state with high positions until the collapse of the empire. A large portion of influential entities, such as the Ottoman Special Organization, Hamidiye regiments, and the Committee of Union of Progress were made up by Circassians. Key figures include Eşref Kuşçubaşı and Mehmed Reşid. Circassians in the Ottoman lands embraced their Caucasian identity, while also maintaining a primary Ottoman-Muslim identity. After the 1908 Revolution in the Ottoman Empire, Circassian nationalist activities started. Organizations such as the Çerkes İttihat ve Teavün Cemiyeti (Circassian Union and Charity Society) and Çerkes Kadınları Teavün Cemiyeti (Circassian Women's Mutual Aid Society) published journals in the Circassian language and opened Circassian-only schools. Some were less cultural and more political, such as the Şimalî Kafkas Cemiyeti (North Caucasian Society) and the Kafkas İstiklâl Komitesi (Committee for the Liberation of Caucasus), both of which aimed for the independence of Circassia and were supported by the CUP.[40][41]

Circassian nationalism in modern times

editThe modern movement has its roots in secret societies, as well as organizations during the perestroika period under Mikhail Gorbachev.

In the 20st and 21st centuries, Circassian nationalism is becoming increasingly popular among younger Circassians, and to a lesser extent, older ones as well.[42] Reports about the Russo-Circassian war and the Circassian genocide and books written about it by Circassian writers also contributed to the rise of nationalistic feelings among Circassians.

Modern Circassian nationalism is the ideology of several activist groups in the "Circassian belt" of autonomous republics in Russia, as well as in areas where the Circassian diaspora is, and in Abkhazia, which has ethnic ties to Circassia. The widely criticized 1999 election in Karachay-Cherkessia where the Circassian candidate was beaten became a symbol of martyrdom, causing huge crowds of Abazins and Circassians in the capital to lead protests.[43]

Attempting to achieve recognition of the Circassian genocide is also a very prominent movement among Circassians, though it is not necessarily purely nationalist, but more humanist. Another major part of the movement, often tied into this, is the movement to recreate a "historical Circassia", the core of Circassian nationalism, with its historical territories.

Some Circassian nationalist moderates, such as Cherkesov[44] suggest that, withdrawing from the Russian federation is not a must, and a unified Circassia still within Russia is good enough.[45] Nonetheless, most assert that this unified Circassia within Russia should have one official language, Circassian (Today categorized by the Russian government as two separate languages: Adyghe and Kabardian).

The movement to split Karachay–Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria has won itself the official support of many Circassians (especially in Karachay–Cherkessia, where Karachay and Russians dominate government posts) as well as the influential Circassian organization "Adyghe Xase".[14]

After the crisis involving the ethnic identity of the man who first scaled Mt.Elbrus, a group of young Circassians, led by Aslan Zhukov, reconquered the mountain in a symbolic move. Aslan Zhukov (also 36-year-old founder of Adyghe Djegu, another major Circassian nationalist organization) was then murdered on 14 March 2010 by a gunshot in a dark alley.[46][47][48] His death spurred another round of rioting among Circassians, who variously attribute his death to the Russian government, the Russians in the republic or the Karachay, some combination, or all of them. The head of the republic said that his death should not be painted in ethnic terms but this only resulted in the addition of him to the list of possible culprits from the Circassian point of view.

Rise of the modern movement

editModern Circassian nationalism initially started to rise during the glasnost and perestroika eras and peaked in the early 1990s. It was well received by many ethnic Circassians. Circassian nationalists exerted persistent pressure on officials, and many of their demands had to be accepted by regional authorities, except in Karachay-Cherkessia, where clashes with the Karachays were common.

When Vladimir Putin became the president, the International Circassian Association (ICA), was taken over and turned into a pro-Russian puppet organization. Members who opposed were removed from the political arena by means of imprisonment and assassinations, and by the end of 2000, there was little to no independent nationalist organizations. In the 2010s, however, Circassian nationalism went through a renaissance, especially after the 2014 Sochi Olympics, which was hosted in Sochi (the place were the Battle of Qbaada took place and the Circassian genocide was initiated), Circassian nationalism rose in popularity.

Meanwhile, in the diaspora, a cultural reawakening happened. Contacts were being established with their homeland, but also, many institutions were founded to strengthen the Circassian identity within the diaspora. Circassian nationalism is now almost universally popular among younger Circassians, who have started to study and learn their language, Adyghe Xabze, history, and adapt their lives to serve their nation.[1] Despite the fact that some of the present leaders of the Circassian nationalist movement were active in the early 1990s, the vast majority of current activists are new. They are usually between the ages of 18 and 28.

Support

editIn the homeland

editIn Adygea

editAn organization calling itself "Union of Slavs", led by Nina Konovaleva and Boris Karatayev was created in 1991 to counter the activities of Circassian organizations such as Adyghe Xase, and prevent Circassians from having any kind of position with prestige and power, as well as to "protect Russians from Circassian control of Circassia".[14] In 1991, Union of Slavs actively opposed the establishment of Adygea as separate from Krasnodar Krai as an ethnic republic within Russia, stating that Circassians were only "barbaric people that has been dealt with". The Union of Slavs has called the increasing autonomy of Adygea and the activism in Karachay–Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria part of a "dangerous conspiracy" to create a "Greater Circassia", achieve demographic dominance by repatriating Diaspora Circassians, and then marginalize or even expel the Russian residents ("colonists", in Circassian ideology).[14][49] The group has called for the complete and full abolition and integration of the three Circassian republics (two of which are also shared with Karachays or Balkars) to neighboring Russian krais due to "Russians losing their superior status, and Circassians trying to gain influence on their lands".[14][50]

In Adygea, a number of reports came in August 2009 about Russian Orthodox crosses being thrown off mountains by Circassians in symbolic demonstrations against the Union of Slavs and the Russian Orthodox Church, viewed by Circassians as symbols of oppression and colonisation.[51] The perceived favoritism of Moscow towards the Slavs is also a major bone of contention amongst Circassians.[52]

In Karachay-Cherkessia

editIn November 2009, in response to a news article very heavily insulting the Circassians, Circassian activists ramped up efforts with the scheduling of a mass-protest against the "ignorance of the Russian government and the Russian people in Karachaevo-Cherkessia".[53] However, the government canceled the gathering, saying it would be banning any and all public gatherings for an indefinite period to prevent the spread of the H1N1 flu virus.[53][54] However, the head of the Circassian youth movement, Timur Jujuev, said "All the public markets continue working on a regular basis, so why are you stopping only us and not others? We are going to organize the demonstration and wear surgical masks to protect ourselves. This is not the will of one or two men; it is the will of an entire ancient nation, this is our land for thousands of years, and we have right to say what we think".[53][55]

There has also been a swift escalation of tension between the Circassians and the non-Circassians in the three republics (Russians, Karachay and Balkars). While the Russians in Adygea demand the abolition of Adygea, the Karachay have taken to a strategy of keeping Circassians out of office- Jamestown reports that "Over the last seven months, the Karachay majority in the KCHR parliament have repeatedly banned the Circassian candidate Vyacheslav Derev from taking a position in the Russian Federation Council".[53][56] Furthermore, for the last 31 years, no Circassian has held the highest post in the republic, as the Soviet and then Russian officials always appointed Karachays, because of their loyalty to the Russians.

There is a movement, highly popular among both Circassians and Karachay, to divide the republic into monoethnic units of Cherkessia and Karachayia, perhaps to prepare these units for a merger.[57]

There have also been numerous clashes between Karachay and Circassian historians over various historical issues. One of the most scandalous cases occurred when Karachay historians claimed that the conqueror of Mt. Elbrus (Khashar Chilar in Circassian, Hilar Hakirov in Karachay) was a Karachay rather than a Circassian from Nalchik, going against the testimony of the members of the early 19th century expedition to the top of the mountain which he led.[53] On 20 November, a poster hailing the "great Karachay hero" Hakilov in Cherkessk was burned and destroyed by unknown perpetrators.[53][58]

What actually started the protests by Circassians in Karachay-Cherkessia was a news article by the local newspaper Express-Post.[53] According to Circassians, it denied the well established and recognised fact that the Circassian village of Besleney had saved dozens of Jewish children from the Nazis, prompting a joint Jewish-Circassian contingent to protest the existence of the report as well as an outcry in Circassian-operated independent media sources.[59] Express-Post apologized later, but it was these protests that were planned to be spread to the capital to protest the general "deep oppression" of Circassians.[53][54]

In Kabardino-Balkaria

editIntended to coincide with protests in Karachay–Cherkessia, Circassian youth groups held mass protests in Kabardino-Balkaria on 17 November 2009. It was attended by about 3000 people (considering that it was limited to the city of Nalchik and the small population of the republic's Circassian population alone, let alone in that city, this is seen as a huge figure).[53] Ibragim Yagan, a leader of a Circassian NGO released a video online. It featured him standing under the Circassian flag, called upon all Circassian youth to wake up to claim their rights and historic lands. He said that "First we have been genocided. Then, we have been constantly watched, followed, blackmailed for our political activities. But we cannot lose anymore, because we have already lost everything."

It is important to note that unlike in Adygea (22% Circassian) and Karachay–Cherkessia (16% Circassian), Kabardino-Balkaria has a clear Circassian majority (55% Circassian). However, "after the parliament of KBR ratified the bill 'On land and territory', each Balkar living in KBR in turn has received 10.6 hectares of the land while only 1.6 hectares belong to each Circassian"[53] noted Jelyabi Kalmykov, and this soon became a rallying cry at the protest.[60] Ruslan Keshev, the leader of the Circassian Congress in Kabardino-Balkaria declared that "If the government does not listen to us we are ready for radical actions. This is the only homeland we have."[53]

On 29 December 2010, a prominent Circassian ethnographer and Xabze advocate Arsen Tsipinov[61] was assassinated by radical Islamist terrorists who had accused him of being a mushrik (idolatrous disbelief in Islamic monotheism) and months earlier threatened him and others they accused as idolaters and munafiqun ("hypocrites" who are said are outwardly Muslims but secretly deny Islam) to stop "reviving" and diffusing the rituals of the original Circassian pre-Islamic traditions.[62][63]

In June 2019, Martin Kochesoko, a defender of Circassian rights and an advocate of Xabze, was sentenced by the Russian government to life in prison.[64] After Circassian nationalists around the world pressured the Russian government,[65][66] his sentence was commuted and Kochesoko was placed under house arrest.[67]

On 25 September 2022, Circassians in Nalchik protested against the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[68][69] One day later, they protested in Nartkala.[70][71] Five Circassian nationalists, Valery Khazhukov, Marks Shakhmurov, Aslan Beshto, Alik Shashev and Timur Alo issued a 1,250-word letter to the heads of the Circassian republics to stop mobilization.[72][73][74]

In Sochi and other parts of the Caucasus

editIn 2011, a peaceful independence movement named "May 21 Call to Action – Where is Circassia?" was initiated. This movement began with the philosophy that the pencil is greater than the sword, and wished to continue its efforts peacefully, however it gradually disappeared as members began to receive armed death threats from Russian fanatical nationalists.[75]

Russian State television presenter Mikhail Leontiev, who was disturbed by the demolition of a monument (which was built in Adler near Sochi glorifying the leaders who committed several massacres during the Circassian genocide) made controversial statements.[76] Senior politicians and administrators also made insults against Circassians. The directors of the Russian state-owned companies Gazprom and Rumsfelt and various politicians made statements containing severe insults to the Circassians over the removed monument. Russian technology designer Artemy Lebedev made statements with heavy insults and genocide implications against Circassians.[77] Immediately after, Lebedev was given the "Homeland Order of Merit", one of the top-ranking decorations in Russia, which raised the suspicion that these people were being protected by the state.[77]

In the diaspora

editIn Turkey

editCircassians are one of the largest ethnic minorities in Turkey, with a population estimated to be 2 million. According to the EU reports there are three to five million Circassians in Turkey.[78] The closely related ethnic groups Abazins (10,000[79]) and Abkhazians (39,000[80]) are also often counted among them. Turkey has the largest Circassian population in the world, around half of all Circassians live in Turkey, mainly in the provinces of Samsun and Ordu (in Northern Turkey), Kahramanmaraş (in Southern Turkey), Kayseri (in Central Turkey), Bandırma, and Düzce (in Northwest Turkey), along the shores of the Black Sea; the region near the city of Ankara.

All citizens of Turkey are considered Turks by the Turkish government and any movement that goes against this is heavily suppressed, but it is estimated that approximately two million ethnic Circassians live in Turkey. The "Circassians" in question do not always speak the languages of their ancestors, and in some cases some of them may describe themselves as "only Turkish". The reason for this loss of identity is mostly due to Turkey's Government assimilation policies[81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93] and marriages with non-Circassians.

Circassians are regarded by historians to play a key role in the history of Turkey. Some of the exilees and their descendants gained high positions in the Ottoman Empire. Until the end of the First World War, many Circassians actively served in the army. In December 1922, May and June 1923, the Turkish government removed 14 Circassian villages from Gönen and Manyas regions, without separating women and children, and drove them to different places in Anatolia from Konya to Sivas and Bitlis, to mix with Turks and assimilate. Circassian nationalists often state that this incident had a great impact on the assimilation of Circassians. After 1923, Circassians were restricted by policies such as the prohibition of Circassian language,[81][84][88][89][85][94][91][95][86] changing village names, and surname law[85][86][87] Circassians, who had many problems in maintaining their identity comfortably, were seen as a group that inevitably had to be assimilated.

Although the Circassians in Turkey were forced to forget their language and assimilate into Turkish, a small minority still speak their native Circassian languages as it is still spoken in many Circassian villages, and the group that preserved their language the best are the Kabardians.[96] With the rise of Circassian nationalism in the 21st century, Circassians in Turkey, especially the young, have started to study and learn their language, history and culture. The largest nationalist association of Circassians in Turkey,[97] KAFFED, is the founding member of the International Circassian Association (ICA).[98]

December 2021 events

editAccording to Fahri Huvaj, a prominent Circassian nationalist, the Circassian population has gone through assimilation in the world and now approximately only one fifth of Circassians can speak their language and that the Circassian language and culture is about to disappear from Turkey. UNESCO reports state that Adyghe and Abkhazian are among the "severely endangered" languages in Turkey.[2]

In December 2021, a Deutsche Welle Turkish language documentary featured a story in which a group of Circassians stated that "Circassians just want to keep their culture alive". This led to discussions regarding the state of Circassian assimilation in Turkey[99][100] and gave rise to heavy xenophobia, racism and hate speech in Turkish media questioning loyalty of Circassians to the Turkish state and accusing Circassian NGOs of playing in foreign hands. Turkish ultranationalists were seen posting genocidal and racist quotes of Nihal Atsız.[2] Turkish Neo-Nazi groups called for a full-scale genocide of people with full or partial Circassian descent.[101]

Most Circassian organizations, including KAFFED, the biggest one, confirmed Deutsche Welle's claims while still declaring loyalty to the state and calling for friendship between Circassians and Turks. However, some smaller local organizations like Çerkes Forumu denied the claims. Çerkes Forumu's statement read: "We are Circassians. There are no traitors among us. You can not turn us into traitors. Stop lying."[102]

İlber Ortaylı, often dubbed the best historian of Turkey, also commented on the matter. Ortaylı stated: "Now it's time for the Circassian issue... Circassians of Turkey have always adhered to the principles of this state. Thank God, I have never seen anyone who is bored with their Circassianism and who hides it. This is a healthy feeling. Yes, Turkish assimilation policies in the 1940s were real... But do I need to remind you what Germany was doing in the 1940s? The Circassian language is so difficult that even the best linguists in the world could not learn it. Turkey cannot teach you this language. You have to learn from your mother and father. I hope that our Circassian brothers and sisters keep their culture alive. Nobody would want their culture to die."[103][104][105]

In Syria

editWhen Circassian exiles arrived in Syria, there were rarely any obtrusions against the local Arab population, which welcomed the Circassian immigrants.[106] Because of their Muslim religion, which was also the dominant faith in Syria, and their arrival to the region well before the struggle for independence from the Ottomans and later the French, the Circassians played a role in the founding of the modern state of Syria and immediately became full citizens.[107] However, because of the integration of a number of Circassian cavalry units in the French Army of the Levant, and particularly due to their role in quelling the Druze forces of Sultan Pasha al-Atrash during the Great Syrian Revolt (1925–27), relations with the Arab majority became tense in the early years of the republic. A minority of Circassians in the Golan Heights petitioned for autonomy from Damascus during the French Mandatory years.[108][109]

In the past Syria's Circassian community mainly spoke Adyghe and today some still speak Adyghe among themselves, although all learn Arabic in school, as it is the official language of the state. English is also studied.[110] The Syrian Circassians see nationalism as "protecting the culture" and unlike other non-Arab Sunni Muslim minorities in Syria, such as the Turkomans, the Circassians have maintained a distinct identity, although in recent times they have become increasingly assimilated.[108] During weddings and holidays, some members of the community wear traditional dress and engage in folk songs and dance.[110]

Circassians are generally well-off, with many being employed in government posts, the civil service and the military.[110] In the rural regions, Circassians are organized by a tribal system. In these areas, the communities mostly engage in agriculture, especially grain cultivation, and raise livestock including horses, cattle, goats and sheep. Many also engage in traditional jobs as blacksmiths, gold and silversmiths, carpenters and stonemasons.[108]

In Israel

editThe Circassian exiles established Kfar Kama in 1876 and Rehaniya in 1878.[36][37] After having been deported a second time, this time from the Balkans, by Russia, Ottoman authorities settled Circassians in areas of the Levant as a bulwark against the Bedouins and Druze, who had at times resisted Ottoman rule as well as any hint of Arab nationalism, while avoiding settling Circassians among the Maronites due to the international problems it could cause.[111][38]

At first, the Circassian settlers faced many challenges. The Arabs viewed them very negatively, and clashes occurred, which started an ongoing rivalry between the Circassians and the local Arabs. Throughout the time of the Ottoman Empire, Circassians kept to themselves and maintained their separate identity, even having their own courts, in which they would tolerate no outside influence, and various travelers noted that they never forgot their homeland, for which they continually yearned.[28]

Although Circassians serve in the IDF, and have "prospered" as part of Israel, while preserving their language and culture,[37][112] for most Israeli Circassians, their primary loyalty remains toward their scattered nation with, for some, a desire to "gather all the Circassians in the same place, whether it's autonomy, a republic within Russia, or a proper state".[37] Influenced by the global movement of Circassian nationalism, some Israeli Circassians have returned to Russian-ruled Circassia despite the current political situation in the North Caucasus, much to the dismay of their Israeli Jewish neighbors who would rather they stay.[113] Some Circassians who emigrated to Circassia have returned after becoming disillusioned with the low standard of living in the Circassian homeland, caused by Russian policies, though some have stayed.[113]

In Jordan

editThe Circassian settlers mainly spoke the Circassian dialects of Kabardian, Shapsug, Abzakh and Bzhedug, but there were also Abkhazian and Dagestani language speakers.[114] The group's cultural identity in Jordan is mainly shaped by their self-images as a displaced people and as settlers and Muslims. Beginning in the 1950s, Circassian ethnic associations and youth clubs began holding performances centered on the theme of expulsion and emigration from the Caucasus and resettlement in Jordan, which often elicited emotional responses by Circassian audiences. Eventually the performances were made in front of mixed Circassian and Arab spectators in major national cultural events, including the annual Jerash Festival of Arts. The performances typically omit the early conflicts with the indigenous Arabs and focus on the ordeals of the exodus, the first harvests and the construction of the first Circassian homes in Jordan. The self-image promoted is of a brave community of hardy men and women that long endured suffering.[115] In 1932 Jordan's oldest charity, the Circassian Charity Association, was established to assist the poor and grant scholarships to Circassians to study at universities in Kabardino-Balkaria and the Adygea Republic. The Al-Ahli Club, founded in 1944, promoted Circassian engagement in sports and social and cultural events in Jordan and other countries, while the establishment of the Folklore Committee in 1993 helped promote Circassian traditional song and dance. Today, an estimated 17% of the Circassian community in Jordan speak Adyghe.[116]

Circassians, together with Chechens, are mandated 3 seats in the Jordanian parliament.[117] However, Circassians also produce a disproportionate amount of ministers, which some Jordanians regard as an unofficial quota.

On 21 May 2011, the Circassian community in Jordan organised a protest in front of the Russian embassy in opposition to the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, because the site of the Games was allegedly being built over the site of mass graves of Circassians killed during the Circassian genocide of 1864.[118]

In Iraq

editLike all Iraqis, Circassians in Iraq faced various hardships in the modern era, as Iraq suffered wars, sanctions, oppressive regimes, and civil strife.[119] The overall number of Circassians in Iraq is estimated to be between 30,000 and 50,000,[120] however the total number is unknown.[121]

Today, although it is understood that many Circassians have ethnically assimilated into the Iraqi population, becoming Arabicized or Kurdicized,[121] the few people who managed to preserve their identity continue to engage in nationalist activities. These people have originally integrated into Iraqi society while preserving their traditional culture and customs, such as the Xabze culture. They continue to preserve certain traditions in wedding ceremonies, birth ceremonies, and other special occasions, and to cook their traditional cuisine.[122]

In Iran

editDespite heavy assimilation over the centuries, Circassian settlements have lasted into the 20th century. However, no sizable number of Circassians in Iran speak their language anymore.[123][124][125] Because of this, Circassians are rapidly being assimilated into Persian and Azerbaijani cultures, and although there may be nationalist individuals, there is no Circassian nationalist movement in Iran.

In Egypt

editCircassians in Egypt have a long history. They arrived in Egypt during the Mamluk and Ottoman era, although a small number migrated as muhajirs in the late 19th century as well. The Circassians in Egypt were very influential from the 13th century. They were deeply rooted in Egyptian society and the history of the country. For centuries, Circassians have been part of the ruling elite in Egypt, having served in high military, political and social positions.[126] The Circassian presence in Egypt traces back to 1297 when Lajin became Sultan of Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Under the Burji dynasty, Egypt was ruled by twenty one Circassian sultans from 1382 to 1517.[127][128][129][self-published source] Even after the abolishment of the Mamluk Sultanate, Circassians continued to form much of the administrative class in Egypt Eyalet of Ottoman Empire, Khedivate of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt and Kingdom of Egypt.[126] Following the revolution of 1952, their political impact has been relatively decreased.

Although many Egyptian Circassians exhibit physical characteristics attributed to their forefathers, those with far-removed Circassian ancestry were assimilated into other local populations over the course of time. With the lack of censuses based on ethnicity, population estimates vary significantly. Mainly of mixed Abaza, Adyghe and Arab origin, the Abaza family is the largest extended family with many thousands of members.[130][131][132][133] Egypt's largest aristocratic family, it has played a long-standing role in Egyptian cultural, intellectual, and political life. Like in Iran, although there may be nationalist individuals, there is no Circassian nationalist movement in Egypt.

In Europe and North America

editOut of the Circassians in Europe, only 18% declared fluency in their native language.

There is a small community of Circassians in Ukraine, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia. A number of Adyghe also settled in Bulgaria and in Northern Dobruja, which now belongs to Romania (see Circassians in Romania), in 1864–1865, but most fled after those areas became separated from the Ottoman Empire in 1878. The small part of the community that settled in Kosovo (the Kosovo Adyghes) moved to the Republic of Adygea in Russia with the unexpected support and donations of Muammar Gaddafi in 1998. The majority of the community, however, remained in Kosovo where they have been well established and integrated into Kosovan society. Many members of this community can be identified as they carry the family name "Çerkezi", or "Qerkezi". This community is also well established in the Republic of North Macedonia, usually mingling with the Albanian Muslim population. There are Circassians in Germany and a small number in the Netherlands. The Circassians in all of these European communities may have varying degrees of nationalism, however especially in Germany, there are many Circassian nationalist organisations.

Numerous Circassians have also immigrated to the United States and settled in Upstate New York, California, and New Jersey. There is also a small Circassian community in Canada. The situation in these regions can be compared with the situation of Turkish Circassians.

Russian recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia

editThe Russian recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is also an issue among Circassian nationalists. On one hand, Circassians are often highly enthusiastic to help the Abkhaz, who they view as brothers, and are enthusiastic also for Abkhazia's independence.[134] On the other hand, however, it evidences a perceived double standard used negatively on the Chechens (Circassians also see as brothers, and supported during the First Chechen War), and to a lesser extent, the Circassians as well.[135][136] Paul A. Goble noted that the recognition of South Ossetia, in addition to enraging the Chechens and Ingush, also radicalized many Circassians against Russia, because of the mass of double standards.[137]

There is a large amount of cooperation between Circassian activists and Abkhazia as well: Circassians poured into Abkhazia to assist them in their war for independence against Georgia, and most organisations dedicated to independence of Circassia or promotion of Abkhazia are linked to their cross-Caucasus counterpart. According to Western Circassologist John Colarusso, some Circassians consider Abkhazia a possible addition to Circassia, however only if the Abkhaz themselves wish to join.

Repatriation

editRepatriation has been a major issue. The Russian state, as well as Russians in general, are strictly against any return of the Circassians to their homeland, stating it was the Russian state who exiled the Circassians in the first place for "security reasons", and letting them back would be "dangerous". while Circassians living in Circassia view it as the only way to revive the nation and save it from extinction.

The Circassians have set up several organizations with the explicit goal of encouraging the return of their "brothers". The most notable of these is the ICA (International Circassian Association)'s "Repatriation Committee", which has branches in several countries.

Russia has a double-digit official repatriation quota for Circassians viewed by many scholars (Colarusso, Henze, etc.) as being an attempt to prevent the Circassians, who are viewed as a threat, from returning.

On 9 August 2009, Adygea officially attempted to overrule the Russian immigration quota for Circassians by putting forth its own de facto quota, which was drastically higher, allowing many more Circassians to return to their homeland.[138] According to Western Circassologist John Colarusso, the movement to allow and encourage Circassian return to their homeland (hence, changing the demographics in a way that is advantageous for the Circassians and disadvantageous for the Russians) is one of the major objectives and rallying points of the modern movement.[139][140]

Russia has also set up several barriers. According to an essay by Cicek Chek, these include:

Circassians living in the North Caucasus and the more numerous Circassians living in the Diaspora have been seeking a radical simplification of the procedures for the repatriation of the community. Most Circassians who have tried to return have fallen under the provisions of the 1991 Russian citizenship law which requires that:

- they give up their previous citizenship,

- live in the country for five years before getting Russian citizenship,

- know perfect Russian, and pass a test on the Russian Constitution,

- keep a large sum in a bank of the republic that they try to acquire the citizenship from, and

- people holding non-ordinary passports (diplomatic, privileged, etc) could not apply at all.

The situation has further deteriorated as a result of the adoption in 2003 of the Russian law on the legal status of foreign citizens living in the Russian Federation. That measure makes it even more difficult for Circassians from the Diaspora to return. Despite official statements from Moscow favoring increased repatriation, the current repatriation regime has been a complete failure by any measure.[141]

Additionally, many Circassians in the diaspora opt not to return for additional reasons of inconvenience, losing the job and economic well-being, losing contact with friends, family; or due to assimilation, they love the diaspora they live in more than their homeland.

There have been numerous instances of murders of returnee Circassians by ethnic Russians living in both Krasnodar and Adygea. According to Circassologists, "the risk of death for Circassians who return to their homeland is very high" and "the Circassian genocide never ended".

It has been reported that the fact that Russia's repatriation policies have shown heavy favoritism to ethnic Russians and have granted very few if any Circassians the right to return is another major grievance, especially considering that the return of Circassians to Russia would aid Russia in its attempts to overcome its crisis of declining population.[142]

Diaspora renaissance

editIn the first decade of the 21st century, the Circassian diaspora abroad has begun experiencing a cultural reawakening. Contacts are being established with their homeland, but also, more importantly, there are now many institutions being founded to strengthen the Circassian identity within the diaspora. In 2005, the Circassian Education Foundation, a scholarship fund for Circassians, was founded in Wayne, New Jersey, USA. It is, in fact, a creation of a mother-organization, the Circassian Benevolent Organization. It has since given scholarship funds to Circassians across the US. The organization has also worked on a project of making a free online Circassian-American English dictionaries which will then, it hopes, be used by Circassians for their language so they can, in turn pass it on to their children as well as revitalize it, as a defence against "Russia's constant attempts to erase the Circassians from history".

The Circassian diaspora in the Middle East also are undergoing a cultural reawakening, largely due to the reestablishment of contacts with their homeland, however, unlike that in Western countries (primarily the US, Germany, The Netherlands, Austria and Israel), it is often paired with tension between Circassians and the ethnic majority of the country, Arabs or Turks.[143] The governments of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Russia and Iran have all forced assimilation of Circassians and suppressed their culture in the past and suppressed various attempts at past renaissances.[144] Nonetheless, in the past few years, in many of these countries, the diaspora has become much more aware of their identity and active. "NART TV", a program broadcasting from Adygeya about Circassian identity, history and life, is now broadcasting in many Middle Eastern countries, including Israel and Jordan, but it was not allowed in Turkey.[145]

On 8 August 2010, a university opened in Amman, Jordan, specifically for Circassians to preserve Circassian heritage and culture, with classes in the Circassian language and on Circassian culture and history in addition to practical topics.[146]

Russian reaction

editRussians may view Circassian nationalism extremely fearfully and suspiciously, not simply because it claims a chunk of what Moscow considers its territory, but because, just as was the case with Chechnya, the Baltics, and so on, nationalist movements may result in the loss of the previous prestige and dominance by ethnic Russians, a stigmatization of the Russian language, and the re-establishment of native dominance (hence, the "South Africa" syndrome).[14]

As a result of tensions, politics in all three republics are often highly ethnic-based, and in Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia, the dispute is often three-way (Russians vs. Circassians and Abazins vs. Karachay in Karachay–Cherkessia; Russians vs. Kabardins vs. Balkars in Kabardino-Balkaria).

While Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay–Cherkessia's non-Circassian leaders have come under fire from Circassian nationalists for "oppression", ethnic Adyge leader Aslan Dzharimov of Adygea styled himself as a moderate who would balance the centralizing urges of Moscow and the Russians against the autonomism/separatism of the Adyge.[147] Although originally popular on this premise, he soon ended up angering both sides, and Adyghe Xase denounced him as a collaborationist and "traitor to the Circassian nation".

Russians may often view the three republics as integral parts of Russia, especially since Russians are an overwhelming majority of the resident population in Adygea.

The Russian government has taken to either trying to silence the nationalism or trying to gain control over individual Circassian activist groups.[148] Analysts, even Russians such as Sergei Markedonov[149] have voiced concern over what they perceive as the continuing "radicalization" of Circassian youth due to the Kremlin's attempts to control them, and are disappointed that Medvedev continues this policy.[150]

In addition, Russia officially keeps a very low immigration quota for Circassians – as low as 50 (though the only republics Circassians would likely to immigrate to are those in former Circassia). The government of Adygea, however, has seized the opportunity to override this quota for their own territory with their own version: 1400 per year for Adygea alone (rather than 50 per year for all of Russia).[138][151] After Russian protest at this action, Adygea said that they were in fact acting on Yeltsin's own words – for republics to "take as much sovereignty as they can swallow".[152]

Russia has criticized[153][154] articles in the constitutions of the three republics discussing heritage, language and the like and labeling them as "separatist", recommending they be edited.

Some websites, such as CircassianWorld[155] have published various articles of stories from Circassian activists about them (the activists) being intimidated by "FSB veterans", as the activists claim they identified themselves.

Russia has denounced several of the assertions that the Adygei have of their history (in addition to Ukrainian accounts of Holodomor and Chechen and other accounts of the perceivedly genocidal deportation to Siberia) – including the genocide – as false and "fabrications", and as attempts to throw tar on Russia's reputation.[156]

The Cossacks, even more than other Russians, are highly antagonistic towards Circassian nationalism, as it is towards their aims, which include the revival of traditional Cossack paramilitary forces, already underway in Russia (see Cossacks and related pages). Circassians believe that will be a tool, as the Cossacks were in the past, for oppression of ethnic minorities and silencing their demands.[14][157]

Many journalists, both Circassian and Russian (for example, Natalya Rykova),[158] have stated that Russian "skinheads" are intrinsically tied to the ethnic tensions in the "Circassian" republics, whose opinions they perceive as being advanced not in the least by the Russian media.[159] According to the above-cited article from Window-On-Eurasia, "Polls show that many Russians believe the problem of hate crimes can be solved either by restricting immigration or by toughening law enforcement", and that "...Confronted with this challenge, the Russian government has largely failed to do what is necessary to contain it. It "liquidated" a special ministry for nationality affairs. It closed the federal program for promoting tolerance and countering extremism. And it fails to provide sufficient funds and staff to other ministries to deal with the challenge." Furthermore, Putin's current policy for internal division of the Russian Federation is not at all pleasing for advocates of self-determination: it advocates "enlargement of regions of Russia".[160] Sergei Mironov stated on 30 March 2002 that "89 federation subjects is too much, but larger regional units are easier to manage" and that the goal was to merge them into 7 federal districts. Gradually, over time, ethnic republics were to be abolished to accomplish this goal of integration.[160][161]

Many people, ranging from Circassian activist coordinators to Akhmed Zakayev, Ichkerian head of government-in-exile to the liberal journalist Fatima Tlisova have speculated that Russia has tried to use a policy of divide and rule throughout the North Caucasus (citing examples of the Circassian vs. Karachai/Balkar rivalry, Ossetian-Ingush conflict, Abkhaz–Georgian conflict, Georgian–Ossetian conflict, interethnic rivalries in Dagestan and even the first Nagorno-Karabakh War, which Russia also insists on mediating), creating "unnatural conflicts" that can only be solved by Kremlin intervention, keeping Caucasian peoples both weak and dependent on Russia to mediate their conflicts.[53] Sufian Jemukhov and Alexei Bekshokov, leaders of the "Circassian Sports Initiative" stated that the conflict "has the potential to blow up the whole Caucasus into a bloody mess with the mass civilian casualties and therefore keep the Circassians from opposing the Sochi Winter Olympics...Moscow plays the conflict scenario when the participants do not have the ability to solve the conflict, but the conflict is absolutely manageable and can be easily solved by its rulers from the Kremlin."[53][162]

2014 Winter Olympics controversy

editIn the lead-up to the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi (once the Circassian capital),[163] Adyghe organizations (plus the Circassian diaspora) in Russia and abroad demanded that the construction of venues at the site of the Circassian genocide should be halted and that the games should not be held to prevent the desecration of Adyghe graves. According to Iyad Youghar, head of the International Circassian Council, "We want the athletes to know that if they compete here they will be skiing on the bones of our relatives."[163] The year 2014 also marked the 150th anniversary of the genocide, which angered Circassians inside and outside Russia. Many protests were held to stop the games, but they ultimately were unsuccessful.[164][165] The protests served as a rallying point for Circassian activist organizations to speak out about their Olympics-related concerns.[163]

Campaign for genocide recognition

editAs of 2021[update], Georgia is the only country to recognize the Circassian genocide; for Abkhazia, Chechnya, Jordan and Turkey, their state officials have acknowledged the genocide although their parliaments have never passed an official resolution to recognise it. In contrast, Russia actively denies the genocide and classifies the plight of the Circassians as just a simple migration.[166][167]

Russian nationalists in the Caucasus region continue to celebrate 21 May as a "holy conquest day" each year, when the Circassian deportation began. Circassians commemorate 21 May as a day of mourning every year to commemorate the Circassian genocide. On this day, Circassians from all over the world fill the streets and organize protests against the Russian government; Circassian banners and flags are a common sight in certain regions of cities such as Istanbul and Amman during these events.[168][169]

In more recent times, scholars and Circassian activists have proposed that the deportations could be considered a manifestation of the modern day concept of ethnic cleansing, noting the systematic massacre of villages by Russian soldiers[170] that was accompanied by the Russian colonization of these lands.[171] They estimate that some 90 percent of Circassians (estimated at more than one million)[172] had relocated from the territories occupied by Russia. During these events, and the preceding Caucasian War, at least hundreds of thousands of people were "killed or starved to death", but the exact number is still unknown.[173]

Former President of Russia Boris Yeltsin's May 1994 statement admitted that resistance to the tsarist forces was legitimate, but he did not recognize "the guilt of the tsarist government for the genocide."[174] In 1997 and 1998, the leaders of Kabardino-Balkaria and of Adygea sent appeals to the Duma to reconsider the situation and to issue the needed apology; to date, there has been no response from Moscow. In October 2006, the Adygeyan public organizations of Russia, Turkey, Israel, Jordan, Syria, the United States, Belgium, Canada and Germany have sent the president of the European Parliament a letter with the request to recognize the genocide against Adygean (Circassian) people.[175]

In the late 2000s, the movement to secure recognition for the Circassian genocide, largely taking a leaf out of the book of the Armenians, gained in momentum and popularity.[176] Reasons for this include the controversy surrounding the hosting of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, the recognition of the Armenian genocide in the United States (prompting a bill on the Circassian genocide in New Jersey, where most Circassians in the U.S. live) and the repeated insistence by Russians that the Georgians committed "genocide" against Abkhazians and Ossetians.[177]

Several Circassians attempted to attract global media attention to the Circassian genocide and its relation to the city of Sochi (the host city of the 2014 Winter Olympics) by holding mass protests in Vancouver, Istanbul and New York during the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada.[178]

On 20 March 2010, a Circassian Genocide Congress was held in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, funded in part by the Circassian members of the Western political analysis center, the Jamestown Foundation.[179][180]

A resolution was passed that led to Georgia becoming the first UN-recognized sovereign state to recognize the Circassian genocide.[180] In May 2011, Georgia followed through and recognized the acts as a genocide.[181][182][183] Soon after, the Chechen government-in-exile announced that it commended Georgia's decision. The government-in-exile also called for pan-Caucasian solidarity;[184] as a result, Circassians, Georgians, Chechens and other Caucasian diasporas in European countries staged demonstrations to show their support.[185][186][187] In appreciation for the Georgian recognition, the Georgian flag was seen flying in Nalchik, the capital of Kabardino-Balkaria, which had been a bastion of anti-Georgian sentiment before the recognition.[142]

On 21 May 2011, a monument was erected in Anaklia, Georgia, to commemorate the suffering of the Circassians.[188] In response, a presidential commission was later set up in Russia to try and deny the Circassian genocide, with respect to the events of the 1860s.[189]

In 2014, the Circassian movement culminated in the Circassian protests against the 2014 Winter Olympics. In response to the actualization of the "Circassian issue,"[190] Russia followed the usual path: suppression of Circassian protests, discrediting the Circassian movement by linking it to external factors (the interests of countries such as Georgia, the United States and Israel).[191][192]

On 1 December 2015, on Great Union Day (the national day of Romania), a large number of Circassian representatives sent a request to the Romanian Government asking it to recognize the Circassian genocide. The letter was specifically sent to the President (Klaus Iohannis), the Prime Minister (Dacian Cioloș), the President of the Senate (Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu) and the President of the Chamber of Deputies (Valeriu Zgonea). The document included 239 signatures and was written in Arabic, English, Romanian and Turkish. Similar requests had already been sent earlier by Circassian representatives to Estonia, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland and Ukraine.[193][194] In the case of Moldova, the request was sent on 27 August of the same year (2015), on the Moldovan Independence Day, to the President (Nicolae Timofti), the Prime Minister (Valeriu Streleț) and the President of the Parliament (Andrian Candu). The request was also redacted in Arabic, English, Romanian and Turkish languages and included 192 signatures.[195][196] The Romanian and Moldovan governments ignored the request.

In 2017, as the readiness of Circassians to defend their own identity increased, the Circassian national movement experienced a national upsurge. Several large-scale events took place simultaneously in several regions of Russia that same year on 21 May. Tens of thousands of Circassians in Adygea, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia took part in mourning events dedicated to the anniversary of the end of the Russian-Caucasian War. The multi-million diaspora of Circassians abroad was not left aside, for example, there was a mass procession with national banners of Circassia through the central streets of Turkish cities. For the first time in the history of post-war Circassia, which today exists only in the historical memory of Circassians, commemorative events dedicated to the victims of the Russian-Caucasian war were held in schools, higher educational institutions, and in cities with a compact population of Circassians.[197]

Alexander Ohtov, Russian historian, said the term genocide is justified in his Kommersant interview: "Yes, I believe that the word "genocide" is justified. To understand why we are talking about the genocide, you have to look at history. During the Russian-Caucasian war, Russian generals not only expelled the Circassians, but also destroyed them physically. Not only killed them in combat but burned hundreds of villages with civilians. Spared neither children nor women nor the elderly. They killed and tortured them with no separation. The entire fields of ripe crops were burned, the orchards cut down, people burnt alive, so that the Circassians could not return to their habitations. A destruction of civilian population on a massive scale... is it not a genocide? Who can even claim that?".[198] After this statement, Circassians, especially in the Caucasus, pressured Moscow once again to classify the events as genocide, but no result has been achieved. Most scholars today who specialise in the field agree that the term "genocide" is justified to define the events, except a few scholars of Russia. Some include Anssi Kullberg, Paul Henze, Walter Richmond, Michael Ellman, Fabio Grassi, Robert Mantran, Server Tanilli and İlber Ortaylı.

Modern movement for the rights and freedoms of Circassians

editAs a result of the Tsarist exile (1864), 90% of the Circassian people are diaspora (about 6 million people, including 1.5 million citizens of Turkey). However, this does not prevent Circassian activists from advocating for the revival and development of their native language and the creation of a separate Circassian national republic in the North Caucasus. Russian officials have already expressed concern that the influx of Circassians from abroad will change the ethnic balance in the republic, strengthen the common Circassian identity, and encourage calls to restore statehood and independence.[199]

In March 2019, Circassian activists formed the Coordinating Council of the Circassian Community. The activists seek international recognition of the 1860s genocide and defend their language and the ability to receive education in it. In 2021, Circassian demonstrations were held in several cities despite government repression. The largest rally was held in Nalchik, attended by about 2,000 people. In September 2021, two new independent Circassian organizations were established - the Circassian (Adygean) Historical and Geographical Society and the United Circassian Media Space. Their plans include the study and defense of Circassian history, the return of Circassian topographic names, and the preservation and multiplication of the Circassian language and identity. Circassian activists are focusing on the 2021 census by launching a petition calling on large communities to declare themselves Circassians (indigenous Adygs). Such an initiative encourages rediscovery of Circassian history and the revitalization of Circassian identity, which was divided and distorted by the Tsarist, Soviet, and Russian regimes. On October 3, 2021, leaders of eight Circassian organizations appealed to their brethren across the North Caucasus to use their own self-designation in the census, rather than the alien one imposed on them by Moscow.[200]

In June 2018, a law promoting Russification was passed: the study of all non-Russian languages in schools became voluntary, while the study of Russian remained compulsory. Circassians (Adygs) consider the de facto abolition of indigenous languages as a continuation of the Russian extermination and expulsion of the Circassian population from the North Caucasus, which began in 1864 with deportation and genocide.[201]

Aslan Beshto, chairman of the Kabarda Congress, believes that the main task for Circassians today is to preserve their native language, which is the key to their ethnic identity.[202]

Circassian activists say that Circassian culture is still practically not presented to the public, in particular, there are very few books in the Circassian language.[203]

Asker Sokht, chairman of the public organization Adyge Khase in Krasnodar Krai, also believes that "the main tasks facing Circassians as an ethnic group are the preservation of their language and culture". In 2014, he was detained and sentenced to eight days of arrest. Soht's detention was related to his criticism of the Sochi Olympics, as well as his active public activities.[204]

Since the beginning of 2022, the authorities have been working systematically and systematically to cancel Circassian (Adyghe) commemorative and festive events. Under far-fetched pretexts, they banned the celebration of the Circassian flag day, and later banned the procession that had become traditional in honor of the mourning day of May 21.[205]

Persecution of Circassian activists

editIn May 2014, on the eve of the tragic date (May 21), Beslan Teuvazhev, one of the organizers of a campaign to make commemorative ribbons for the 150th anniversary of the Russian-Caucasian War, was detained by Moscow police officers. More than 70 thousand ribbons were seized from him. Later Teuvazhev was released, but the ribbons were not returned, having found signs of extremism in the inscriptions printed on them. Circassian activists call such an act "a continuation of the policy of oppression of national minorities" of the times of the empire.[206]

In November 2014, the representative of the movement "Patriots of Circassia" Adnan Huade and the coordinator of the public movement "Circassian Union" Ruslan Kesh were among the signatories of the appeal of activists of Circassian public organizations to the leadership of Poland with a request to recognize the genocide of Circassians in the XIX century. In 2015, the activists were subjected to searches and detentions by law enforcement officials.[207][208]

In spring 2017, a court in the Lazarevsky district of Krasnodar Krai sentenced seventy-year-old Circassian activist Ruslan Gvashev for his participation in the May 21, 2017 mourning events dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Russian-Caucasian War. Ruslan Gvashev is a well-known Circassian activist in the region, head of the Shapsug Khase, chairman of the Congress of Adyg-Shapsugs of the Black Sea region, vice-president of the Confederation of Peoples of the Caucasus and the International Circassian Association. Nevertheless, the court found the defendant guilty of organizing an unauthorized rally and imposed a fine of 10,000 rubles on Ruslan Gvashev. Due to the disability of the accused (Ruslan Gvashev has one leg amputated), the court released him directly from the courtroom. The Circassian activist, who does not agree with the offensive, in his opinion, charge, sought help from the Kabardino-Balkarian Human Rights Center in order to obtain a review of his case and recognition of the Circassians' right to hold memorial events.[209][210][211]

Numerous facts of harassment of activists, commissioned trials against the most prominent figures of the Circassian national movement make it necessary to seek a fair solution in international courts.

Thus, the European Court of Human Rights accepted the complaints of Circassian activists accused of extremism by the Russian Themis. The year-long attempt of civil activists from the organization "Circassian Congress" to shed the label of "extremism" ended with an appeal to the European Court. Before seeking justice outside Russia, the activists spent 4 years trying to get justice in Russian courts. All this time, as the activists themselves say, they and their families were under pressure - they received threats from FSB and Interior Ministry officers. The case of civil activists from the Circassian Congress is far from being an isolated one.[212]

The reprisals by the Russian authorities against national minorities and activists of Circassian public organizations defending the rights of these minorities in the North Caucasus have taken on an unprecedented scale.[213]

The danger of the Circassian national movement for Russia lies in its great potential: Circassians are the titular ethnic group in three regions of the North Caucasus - Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia and Adygea. Another circumstance makes the "Circassian issue" particularly alarming for Russia. This is the presence of a multi-million diaspora in the Middle East, which is returning to the North Caucasus due to the horrific war in Syria. According to human rights activists, the increasing cases of persecution of Circassian activists are directly related to the growth of the Circassian movement in virtually all republics of the Russian North Caucasus. This is the largest ethnic group in the region, supported by a multi-million diaspora in the Middle East, including Syria.[214]

Circassophilia in the West

editDuring and after the Enlightenment, Western European cultures showed much interest in the Circassians, specifically their physical appearance, language and culture, portraying the men as especially courageous (a legend that became especially popular in the court of London during the Crimean War when they were allies with Circassia). Circassians were often thought of as being especially beautiful, having curly black hair, light eyes and pale white skin (generally somewhat close to their actual appearance), giving rise to the phenomenon of Circassian beauties.[215]

The Italian and Greek presence in port towns had an effect on both the dialects of the Italians/Greeks and the Circassians around the area (as well as the Abkhazians, if they are to be considered Circassian). The Circassian languages were widely regarded as unique and beautiful by 19th century linguists (today, they are often linked to extinct languages in Anatolia).

Racial scientists, after discovering an intimate similarity between the skull shapes of Caucasians (primarily judged by Circassians, Georgians and Chechens, the most numerous groups), went to declare that Europeans, North Africans and Caucasians were of a common race, termed "Caucasian", or later, as it is known today, as "Caucasoid". Racial scientists went far to emphasize the superior beauty of the Caucasian people, above all the Circassians, referring to them as "how God intended the Caucasian race to be" and that the Caucasus was the "first outpost of the superior race".[216] According to Johann Freidrich Blumenbach, a chief advocate of the Circassophilic theory of Circassians as the prime and most superior examples of Caucasoid race (usually followed then by Georgians in second place), the Circassians were the closest to God's original model of humanity, and thus "the purest and most beautiful whites were the Circassians".[217]

...It is no exaggeration to say that for several decades in the middle of the 19th century "Circassia" became a household in many parts of Europe and North America. Correspondents from major newspapers found their way to Circassia or gleaned information from foreign consuls and merchants in Trebizond and Constantinople. The "Circassian question", the political status of the northwestern highlands of the Caucasus, was debated in parliaments and gentlemen's clubs.[218]

Meanwhile, beauty products got names in the US and Western Europe such as "Circassian Soap", "Circassian Curl", "Circassian Lotion",[219] "Circassian Hair Dye",[220][221] "Circassian Eye Water",[222] etc. The Circassian is also known to be, somewhat correctly, tall and thin. This admiration developed for the Circassians, especially their physique, but also later their culture, which in some ways resembled that of Medieval Europe, such as the feudal system employed by some tribes.

Though Circassophilia already was a fad in the West, it took a suddenly different form during the Crimean War, when the alliance with the Circassians of Britain led to a more understanding, even sympathetic view of them: rather than a simple obsession with their physical characteristics; expressions of solidarity with the "beautiful, honorable Circassians" became a sort of war rally. Britain glumly observed the Muhajirs (Circassian exiles) miserably, only to forget that the Circassians ever existed decades later once Circassia had been annexed by Russia. This had a profound effect on modern nationalism.[223]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Fatima Tlisova. "Support for Circassian Nationalism Grows in the North Caucasus". Georgiandaily.net, through Adyga NatPress. [permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d "Çerkes milliyetçiliği nedir?". Ajans Kafkas (in Turkish). 15 March 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Paul Golbe. Window on Eurasia: Circassians Caught Between Two Globalizing "Mill Stones", Russian Commentator Says. On Windows on Eurasia, January 2013.

- ^ Авраам Шмулевич. Хабзэ против Ислама. Промежуточный манифест.

- ^ Kalaycı, İrfan. "Tarih, Kültür ve İktisat Açısından Çerkesya (Çerkesler)". Avrasya Etüdleri.

- ^ "Biz Kimiz?". TADNET. 29 December 2019. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021.

- ^ "'Çerkes Milliyetçiliği' Entegre (Kapsayıcı) Bir İdeolojidir". www.ozgurcerkes.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "152 yıldır dinmeyen acı". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Kayseri Haberi: Çerkeslerden anma yürüyüşü". Sözcü. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Çerkes Forumu, Çerkes Soykırımını yıl dönümünde kınadı". Milli Gazete (in Turkish). Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "Suriyeli Çerkesler, Anavatanları Çerkesya'ya Dönmek İstiyor". Haberler.com (in Turkish). 5 September 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Dönüş" (in Turkish). KAFFED. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Evimi Çok Özledim" (in Turkish). KAFFED. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Besleney, Zeynel. "A COUNTRY STUDY: THE REPUBLIC OF ADYGEYA". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Özalp, Ayşegül Parlayan. "Savbaş Ve Sürgün, Kafdağı'nın Direnişi | Atlas" (in Turkish). Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Jonty, Yamisha. Circassians United

- ^ Jonty, Yamisha. Profile of the Diaspora: A Global Community

- ^ Smeets, Rieks (1995). "Circassia" (PDF). Central Asian Survey. p. 108.

- ^ The Chechen Nation: A Portrait of Ethnical Features Lyoma Usmanov Jan, 9, 1999, Washington, D.C.

- ^ K. Tumanov was the first to pay attention to the existence of Chechens in ancient times in East Asia and Southern Caucasus. ("The prehistoric language of Caucasus", Tiflis, 1913).

- ^ See Charles King's The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus

- ^ Wood, Tony. Chechnya: the Case for Independence.

- ^ "145th Anniversary of the Circassian Genocide and the Sochi Olympics Issue". Reuters. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Glenny, Misha (2000). The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers. ISBN 9780670853380.

The Porte...used the influx as refugees as an expedient and declared that that the new soldiers should be recruited from the Circassians

- ^ Charles King. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. p. 97.

Part of the Ottomon resettlement strategy was to place Circassians in areas where either Muslim or Turkic populations were low...Circassian families were sent to Syria, the Balkans, and eastern Anatolia and resettled amid restive communities of Arabs, Slavs, Kurds and Armenians.

- ^ King, The Ghost of Freedom, pages 97-98.

- ^ "Syrian Circassians". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ a b Richmond 2013, p. 118

- ^ Rogan 1999, p. 73.

- ^ Tița, Diana (16 September 2018). "Povestea dramatică a cerchezilor din Dobrogea". Historia (in Romanian).

- ^ Parlog, Nicu (2 December 2012). "Cerchezii: misterioasa națiune pe ale cărei pământuri se desfășoară Olimpiada de la Soci". Descoperă.ro (in Romanian).

- ^ Hacısalihoğlu, Mehmet. Kafkasya'da Rus Kolonizasyonu, Savaş ve Sürgün (PDF). Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi.

- ^ BOA, HR. SYS. 1219/5, lef 28, p. 4

- ^ Rogan 1999, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Hamed-Troyansky 2017, pp. 608–610.

- ^ a b Circassians (in Rehaniya and Kfar Kama)

- ^ a b c d Kessler, Oren (20 August 2012). "Circassians Are Israel's Other Muslims". The Forward. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ a b Richmond 2013, pp. 113–114

- ^ Richmond 2013, pp. 113–114, 117–118.

- ^ Besleney, Zeynel Abidin: The Circassian Diaspora in Turkey. Political History, New York 2014, pp. 58-60.

- ^ Üre, Pınar. Circassian nationalism.

- ^ "Youth Activists Unravel Kremlin Status-Quo in the Circassian Heartland: "The Wind of Freedom is Approaching!"". North Caucasus Analysis Volume: 10 Issue: 15. The Jamestown Foundation. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ "Home | Institute for War and Peace Reporting". Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Bella Ksalova (22 January 2010). ""Adyge Khasse": idea of united Circassia is no threat to Russia's integrity". Caucasian Knot. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ Paul Goble (25 January 2010). "United Circassia Said No Threat To Russia but Divided could be". Window on Eurasia. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ "Murder of Circassian Activist Unsettles Multi-Ethnic Karachaevo-Cherkessia". The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Friends of assassinated Aslan Zhukov hold protest action in Karachai-Circassia". Caucasian Knot. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Информационное агентство, новости политики, экономики, диаспоры, спорта, культуры. Главные новости Республики Адыгея, России и мира". natpress.net. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2010.