Valencia (/vəˈlɛnsiə/; Spanish: [baˈlenθja] ; officially in Valencian: València [vaˈlensia]) is the capital of the province and autonomous community of the same name in Spain. It is the third-most populated municipality in the country, with 807,693 inhabitants within the commune,[1] 1,582,387 inhabitants within the urban area[6][7][3] and 2,522,383 inhabitants within the metropolitan region.[2] It is located on the banks of the Turia, on the east coast of the Iberian Peninsula on the Mediterranean Sea.

Valencia | |

|---|---|

| València | |

|

| |

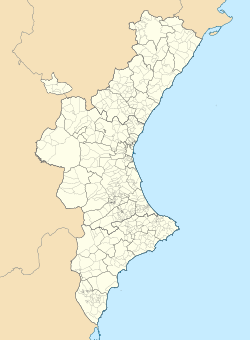

Location of Valencia | |

| Coordinates: 39°28′12″N 00°22′35″W / 39.47000°N 0.37639°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous community | Valencian Community |

| Province | Valencia / València |

| Comarca | Horta of Valencia |

| Founded | 138 BC |

| Districts | 19 districtes

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Ajuntament |

| • Body | Ajuntament de València |

| • Mayor | María José Catalá (since 2023) (PP) |

| Area | |

| 134.65 km2 (51.99 sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 628.81 km2 (242.78 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 15 m (49 ft) |

| Population (2023)[4] | |

| 807,693[1] | |

| • Density | 5,998.5/km2 (15,536/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,595,000[3] |

| • Metro | 2,522,383[2] |

| Demonym(s) | Valencian • valencià, -ana (va) • valenciano, -na (es) |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | €56.413 billion (2020) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET (GMT)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST (GMT)) |

| Postcode | 46000-46080 |

| ISO 3166-2 | ES-V |

| Website | www |

Valencia was founded as a Roman colony in 138 BC under the name Valentia Edetanorum. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Valencia became part of the Visigothic Kingdom from 546 AD and 711 AD. Islamic rule and acculturation ensued in the 8th century, together with the introduction of new irrigation systems and crops. The Aragonese Christian conquest took place in 1238, and so the city became the capital of the Kingdom of Valencia. The city's population thrived in the 15th century, owing to trade with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, Italian ports, and other Mediterranean locations, becoming one of the largest European cities by the end of the century. Already harmed by the emergence of the Atlantic World trade in detriment to Mediterranean trade in global trade networks, along with insecurity created by Barbary piracy throughout the 16th century, the city's economic activity experienced a crisis upon the expulsion of the Moriscos in 1609. The city became a major silk manufacturing centre in the 18th century. During the Spanish Civil War, the city served as the accidental seat of the Spanish Government from 1936 to 1937.[8]

The Port of Valencia is the 4th-busiest container port in Europe and the second busiest container port on the Mediterranean Sea. The city is ranked as a Gamma-level global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[9] Its historic centre is one of the largest in Spain, spanning approximately 169 hectares (420 acres).[10] Due to its long history, Valencia has numerous celebrations and traditions, such as the Falles (or Fallas), which was declared a Fiesta of National Tourist Interest of Spain in 1965[11] and an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in November 2016. In 2022, the city was voted the world's top destination for expatriates, based on criteria such as quality of life and affordability.[12][13] The city was selected as the European Capital of Sport 2011, the World Design Capital 2022 and the European Green Capital 2024.

Name

editThe Latin name of the city was Valentia (IPA: [waˈlɛntɪ.a]), meaning "strength" or "valour", due to the Roman practice of recognising the valour of former Roman soldiers after a war. The Roman historian Livy explains that the founding of Valentia in the 2nd century BC was due to the settling of the Roman soldiers who fought against a Lusitanian rebel, Viriatus, during the Third Raid of the Lusitanian War.[14]

During the period of Islamic rule, the city had the title Medina at-Tarab ('City of Joy') according to one transliteration, or Medina at-Turab ('City of Sands') according to another, since it was located on the banks of the River Turia. It is not clear if an Arabised variant of the Latin name (Balansiyya) was reserved for the wider Taifa of Valencia, or also designated the city.[15]

Via gradual phonetic changes, Valentia became Valencia [baˈlenθja] in Spanish and València [vaˈlensia] in Valencian. In Valencian, an e with a grave accent (è) indicates [ɛ] in contrast to [e], but the word València is an exception to this rule, since è is pronounced [e]. The spelling "València" was approved by the AVL based on tradition after a debate on the matter. The name "València" has been the only official name of the city since 2017.[16] In 2023, the Commission of Culture of the municipal corporation agreed in principle on a dual official denomination Valencia / Valéncia, with the far right managing to impose[editorializing] a non-standard acute accent in the e of the Valencian-language name.[17][18]

History

editRoman colony

editValencia is one of the oldest cities in Spain, founded in the Roman period c. 138 BC under the name Valentia Edetanorum.[19] A few centuries later, with the power vacuum left by the demise of the Roman imperial administration, the Catholic Church assumed power in the city, coinciding with the first waves of the invading Germanic peoples (Suebi, Vandals, Alans, and later Visigoths).

Middle Ages

editAfter the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Valencia became part of the Visigothic Kingdom from 546 to 711 AD.[20] The city surrendered to the invading Moors about 714 AD.[21] Abd al-Rahman I laid waste to old Valencia by 788–789.[22] From then on, the name of Valencia (Arabised as Balansiya) appears more related to the wider area than to the city, which is primarily cited as Madînat al-Turâb ('city of earth' or 'sand') and presumably had diminished importance throughout the period.[23] During the emiral period, the surrounding territory, under the ascendancy of Berber chieftains, was prone to unruliness.[24] In the wake of the start of the fitna of al-Andalus, Valencia became the head of an independent emirate, the Taifa of Valencia.[25] It was initially controlled by eunuchs,[25] and then, after 1021, by Abd al-Azîz (a grandson of Almanzor).[26] Valencia experienced notable urban development in this period.[27] Many Jews lived in Valencia, including the accomplished Jewish poet Solomon ibn Gabirol, who spent his last years in the city.[28] After a damaging offensive by Castilian–Leonese forces towards 1065, the territory became a satellite of the Taifa of Toledo, and following the fall of the latter in 1085, a protectorate of "El Cid". A revolt erupted in 1092, handing the city to the Almoravids and forcing El Cid to take the city by force in 1094, henceforth establishing his own principality.[29]

Following the evacuation of the city in 1102, the Almoravids took control. As the Almoravid empire crumbled in the mid 12th-century, ibn Mardanīsh took control of eastern al-Andalus, creating a Murcia-centered independent emirate to which Valencia belonged, resisting the Almohads until 1172.[30] During the Almohad rule, the city perhaps had a population of about 20,000.[31] When the city fell to James I of Aragon, the Jewish population constituted about 7 per cent of the total population.[28]

In 1238,[32] King James I of Aragon, with an army composed of Aragonese, Catalans, Navarrese, and crusaders from the Order of Calatrava, laid siege to Valencia and on 28 September obtained a surrender.[33] Fifty thousand Moors were forced to leave.[citation needed]

The city endured serious troubles in the mid-14th century, including the decimation of the population by the Black Death of 1348 and subsequent years of epidemics—as well as a series of wars and riots that followed. In 1391, the Jewish quarter was destroyed in a pogrom.[28]

Genoese traders promoted the expansion of the cultivation of white mulberry in the area by the late 14th century, and later introduced innovative silk manufacturing techniques. The city became a centre of mulberry production and was, at least for a time, a major silk-making centre.[34] The Genoese community in Valencia—merchants, artisans and workers—became, along with Seville's, one of the most important in the Iberian Peninsula.[35]

In 1407, following the model of the Barcelona's institution created some years before, a Taula de canvi (a municipal public bank) was created in Valencia, although its first iteration yielded limited success.[36]

The 15th century was a time of economic expansion, known as the Valencian Golden Age, during which culture and the arts flourished. Concurrent population growth made Valencia the most populous city in the Crown of Aragon. Some of the landmark buildings of the city were built during the Late Middle Ages, including the Serranos Towers, the Silk Exchange, the Miguelete Tower, and the Chapel of the Kings of the Convent of Sant Domènec. In painting and sculpture, Flemish and Italian trends had an influence on Valencian artists.

Valencia became a major slave trade centre in the 15th century, second only to Lisbon in the West,[37] prompting a Lisbon–Seville–Valencia axis by the second half of the century powered by the incipient Portuguese slave trade originating in West Africa.[38] By the end of the 15th century Valencia was one of the largest European cities, being the most populated city in the Hispanic Monarchy and second to Lisbon in the Iberian Peninsula.[39]

Modern history

editFollowing the death of Ferdinand II in 1516, the nobiliary estate challenged the Crown amid the relative void of power.[40] In 1519, the Taula de Canvis was recreated again, known as Nova Taula.[41] The nobles earned the rejection from the people of Valencia, and the whole kingdom was plunged into the armed Revolt of the Brotherhoods and full-blown civil war between 1521 and 1522.[40] Muslim vassals were forced to convert in 1526 at the behest of Charles V.[40]

Urban and rural delinquency—linked to phenomena such as vagrancy, gambling, larceny, pimping and false begging—as well as the nobiliary banditry consisting of the revenges and rivalries between the aristocratic families flourished in Valencia during the 16th century.[42] Furthermore, North African piracy targeted the whole coastline of the kingdom of Valencia, forcing the fortification of sites.[43] By the late 1520s, the intensification of Barbary corsair activity along with domestic conflicts and the emergence of the Atlantic Ocean in detriment of the Mediterranean in global trade networks put an end to the economic splendor of the city.[44] The piracy also paved the way for the ensuing development of Christian piracy, that had Valencia as one of its main bases in the Iberian Mediterranean.[43] The Berber threat—initially with Ottoman support—generated great insecurity on the coast, and it would not be substantially reduced until the 1580s.[43]

The crisis deepened during the 17th century with the 1609 expulsion of the Moriscos, descendants of the Muslim population that had converted to Christianity. The Spanish government systematically forced Moriscos to leave the kingdom for Muslim North Africa. They were concentrated in the former Crown of Aragon, and in the Kingdom of Valencia specifically, and constituted roughly a third of the total population.[45] The expulsion caused the financial ruin of some of the Valencian nobility and the bankruptcy of the Taula de canvi in 1613.

The decline of the city reached its nadir with the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1709), marking the end of the political and legal independence of the Kingdom of Valencia. During the War of the Spanish Succession, Valencia sided with the Habsburg ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, Charles of Austria. King Charles of Austria vowed to protect the laws (Furs) of the Kingdom of Valencia, which gained him the sympathy of a wide sector of the Valencian population. On 24 January 1706, Charles Mordaunt, 3rd Earl of Peterborough, 1st Earl of Monmouth, led a handful of English cavalrymen into the city after riding south from Barcelona, captured the nearby fortress at Sagunt, and bluffed the Spanish Bourbon army into withdrawal.

The English held the city for 16 months and defeated several attempts to expel them. After the victory of the Bourbons at the Battle of Almansa on 25 April 1707, the English army evacuated Valencia and Philip V ordered the repeal of the Furs of Valencia as punishment for the kingdom's support of Charles of Austria.[46] By the Nueva Planta decrees, the ancient Charters of Valencia were abolished and the city was governed by the Castilian Charter, similarly to other places in the Crown of Aragon.

The Valencian economy recovered during the 18th century with the rising manufacture of woven silk and ceramic tiles. The silk industry boomed during this century, with Valencia replacing Toledo as the main silk-manufacturing centre in Spain.[34] The Palau de Justícia is an example of the affluence manifested in the most prosperous times of Bourbon rule (1758–1802) during the rule of Charles III. The 18th century was the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, and its humanistic ideals influenced men such as Gregory Maians and Pérez Bayer in Valencia, who maintained correspondence with the leading French and German thinkers of the time.

Peninsular War

editThe 19th century began with Spain embroiled in wars with France, Portugal, and England—but the Peninsular War (Spanish War of Independence) most affected the Valencian territories and the capital city. The repercussions of the French Revolution were still felt when Napoleon's armies invaded the Iberian Peninsula. The Valencian people rose up in arms against them on 23 May 1808, inspired by leaders such as Vicent Doménech el Palleter.[citation needed]

The mutineers seized the Citadel, the Supreme Junta government took over, and on 26–28 June, Napoleon's Marshal Moncey attacked the city with a column of 9,000 French imperial troops in the First Battle of Valencia. He failed to take the city in two assaults and retreated to Madrid. Marshal Suchet began a long siege of the city in October 1811, and after intense bombardment forced it to surrender on 8 January 1812. After Valencian capitulation, the French instituted reforms in Valencia, which became the capital of Spain when the Bonapartist pretender to the throne, José I (Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's elder brother), moved the Court there in the middle of 1812. The disaster of the Battle of Vitoria on 21 June 1813 obliged Suchet to quit Valencia, and the French troops withdrew in July.

Post-war

editFerdinand VII became king after the victorious end of the Peninsular War, which freed Spain from Napoleonic domination. When he returned on 24 March 1814 from exile in France, the Cortes requested that he respect the liberal Constitution of 1812, which significantly limited royal powers. Ferdinand refused and went to Valencia instead of Madrid. Here, on 17 April, General Elio invited the King to reclaim his absolute rights and put his troops at the King's disposition. The king abolished the Constitution of 1812 and dissolved the two chambers of the Spanish Parliament on 10 May. Thus began six years (1814–1820) of absolutist rule, but the constitution was reinstated during the Trienio Liberal, a period of three years of liberal government in Spain from 1820 to 1823.

On King Ferdinand VII's death in 1833, Baldomero Espartero became one of the most ardent defenders of the hereditary rights of the king's daughter, the future Isabella II. During the regency of Maria Cristina, Espartero ruled Spain for two years as its 18th Prime Minister from 16 September 1840 to 21 May 1841. City life in Valencia carried on in a revolutionary climate, with frequent clashes between liberals and republicans.

The reign of Isabella II as an adult (1843–1868) was a period of relative stability and growth for Valencia. During the second half of the 19th century the bourgeoisie encouraged the development of the city and its environs; land-owners were enriched by the introduction of the orange crop and the expansion of vineyards and other crops. This economic boom corresponded with a revival of local traditions and of the Valencian language, which had been ruthlessly suppressed from the time of Philip V.

Work to demolish the walls of the old city started on 20 February 1865.[47] The demolition of the citadel ended after the 1868 Glorious Revolution.[47]

During the Cantonal rebellion in 1873, Valencia was the capital of the short-lived Valencian Canton.[48]

Following the introduction of universal manhood suffrage in the late 19th century, the political landscape in Valencia—until then consisting of the bipartisanship characteristic of the early Restoration period—experienced a change, leading to a growth of republican forces, gathered around the emerging figure of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez.[49] Not unlike the equally republican Lerrouxism, the Populist Blasquism came to mobilize the Valencian masses by promoting anticlericalism.[50] Meanwhile, in reaction, the right-wing coalesced around several initiatives such as the Catholic League or the reformulation of Valencian Carlism, and Valencianism did similarly with organizations such as Valencia Nova or the Unió Valencianista.[51]

20th century

editIn the early 20th century, Valencia was an industrialised city. The silk industry had disappeared, but there was a large production of hides and skins, wood, metals, and foodstuffs, the latter with substantial exports, particularly of wine and citrus. Small businesses predominated, but with the rapid mechanisation of the industry, larger companies were being formed. The best expression of this dynamic was in regional exhibitions, including that of 1909 held next to the pedestrian avenue L'Albereda (Paseo de la Alameda), which depicted the progress of agriculture and industry. Among the most architecturally successful buildings of the era were those designed in the Art Nouveau style, such as the Estació del Nord and the Central and Columbus markets.

World War I (1914–1918) greatly affected the Valencian economy, causing the collapse of its citrus exports. The Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939) opened the way for democratic participation and the increased politicisation of citizens, especially in response to the rise of Conservative Front power in 1933. The inevitable march toward civil war and combat in Madrid resulted in the relocation of the capital of the Republic to Valencia.

After the continuous unsuccessful Francoist offensive on besieged Madrid during the Spanish Civil War, Valencia temporarily became the capital of Republican Spain on 6 November 1936. It hosted the government until 31 October 1937.[52]

Francoist Spain

editIn the Spanish civil war, Valencia was heavily bombarded by air and sea, mainly by the Fascist Italian air force, as well as the Francoist air force with Nazi German support. By the end of the war, the city had survived 442 bombardments, leaving 2,831 dead and 847 wounded, although it is estimated that the death toll was higher. The Republican government moved to Barcelona on 31 October of that year. On 30 March 1939, Valencia surrendered and Nationalist Spanish troops entered the city.

The postwar years were a time of hardship for Valencians. During Franco's regime, speaking or teaching Valencian was prohibited; in a significant reversal, it is now compulsory for every schoolchild in Valencia. Franco's dictatorship forbade political parties and began a harsh ideological and cultural repression countenanced and sometimes led by the Catholic Church. Franco's regime also executed some leading Valencian intellectuals, such as Juan Peset, rector of University of Valencia. Large groups of them, including Josep Renau and Max Aub, went into exile.

In 1943, Franco decreed the exclusivity of Valencia and Barcelona for the celebration of international fairs in Spain.[53] These two cities would hold the monopoly on international fairs for more than three decades, until the rule's abolishment in 1979 by the government of Adolfo Suárez.[53] In October 1957, a flood from the Turia river resulted in 81 casualties and extensive property damage.[54] The disaster led to the remodelling of the city and the creation of a new river bed for the Turia, with the old one becoming one of the city's "green lungs".[54] The economy began to recover in the early 1960s, and the city experienced explosive population growth through immigration spurred by jobs created with the implementation of major urban projects and infrastructure improvements.

Post-Franco

editWith the advent of democracy in Spain, the ancient kingdom of Valencia was established as a new autonomous entity, the Valencian Community, the Statute of Autonomy of 1982 designating Valencia as its capital. Valencia has since then experienced a surge in its cultural development, exemplified by exhibitions and performances at such iconic institutions as the Palau de la Música, the Palacio de Congresos, the Metro, the City of Arts and Sciences (Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències), the Valencian Museum of Enlightenment and Modernity (Museo Valenciano de la Ilustracion y la Modernidad), and the Institute of Modern Art (Institut Valencià d'Art Modern). The various productions of Santiago Calatrava, a renowned structural engineer, architect, and sculptor and of the architect Félix Candela have contributed to Valencia's international reputation. These public works and the ongoing rehabilitation of the "Old City" (Ciutat Vella) have helped improve the city's livability, and tourism is continually increasing.

21st century

editOn 3 July 2006, a major mass transit disaster, the Valencia Metro derailment, left 43 dead and 47 wounded.[55] Days later, on 9 July, the World Day of Families, during Mass at Valencia's Cathedral, Our Lady of the Forsaken Basilica, Pope Benedict XVI used the Sant Calze, a 1st-century Middle-Eastern artifact that some Catholics believe is the Holy Grail.[a]

Valencia was selected in 2003 to host the historic America's Cup yacht race, the first European city ever to do so. The 2007 America's Cup matches took place from April to July. On 3 July 2007, Alinghi defeated Team New Zealand to retain the America's Cup. Twenty-two days later, on 25 July 2007, the leaders of the Alinghi syndicate, holder of the America's Cup, officially announced that Valencia would be the host city for the 33rd America's Cup, held in June 2009.[57]

The results of the Valencia municipal elections from 1991 to 2011 delivered a 24-year uninterrupted rule (1991–2015) by the People's Party (PP) and Mayor Rita Barberá, with support from the Valencian Union. Barberá's rule was ousted by left-leaning forces after the 2015 municipal election, with Joan Ribó of Compromís becoming the new mayor.

Geography

editLocation

editLocated on the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula and the western part of the Mediterranean Sea, fronting the Gulf of Valencia, Valencia lies on the highly fertile alluvial silts accumulated on the floodplain formed in the lower course of the Turia River.[58] At its founding by the Romans in 138 BC, it stood on an alluvial plain of the Turia River several kilometers from the sea.[59]

The Albufera lagoon, located about 12 km (7 mi) south of the city proper (and part of the municipality), was originally a saltwater lagoon, but since the severing of links to the sea, it has eventually become a freshwater lagoon, progressively decreasing in size.[60] The lagoon and its environment are used for the cultivation of rice in paddy fields, and for hunting and fishing purposes.[60]

The Valencia City Council bought the lake from the Crown of Spain for 1,072,980 pesetas in 1911,[61] and today it forms the main portion of the Parc Natural de l'Albufera (Albufera Nature Reserve), with a surface area of 21,120 hectares (52,200 acres). Because of its cultural, historical, and ecological value, it was declared a natural park in 1976.

Climate

editValencia and its metropolitan area have a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) bordering on a semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSh)[62][63] with mild winters and hot, dry summers.[64][65] According to the Siegmund/Frankenberg climate classification, Valencia has a subtropical climate.[66]

The average annual temperature of Valencia is 18.6 °C (65.5 °F); 23 °C (73 °F) during the day and 14.2 °C (57.6 °F) at night. In the coldest month, January, the maximum daily temperature typically ranges from 15 to 20 °C (59 to 68 °F), the minimum temperature typically at night ranges from 6 to 10 °C (43 to 50 °F). December, January and February are the coldest months, with average temperatures around 17 °C (63 °F) during the day and 8 °C (46 °F) at night. March is transitional, the temperature often exceeds 20 °C (68 °F), with an average temperature of 19.3 °C (66.7 °F) during the day and 10 °C (50 °F) at night. During the warmest months – July and August, the maximum temperature during the day typically ranges from 28 to 32 °C (82 to 90 °F), about 21 to 24 °C (70 to 75 °F) at night. The highest and lowest temperatures recorded in the city since 1937 were 44.7 °C (112.5 °F) on 10 August 2023 and −7.2 °C (19.0 °F) on 11 February 1956, respectively.[67] Valencia has one of the mildest winters in Europe, owing to its southern location on the Mediterranean Sea and the Foehn phenomenon, locally known as ponentà.[68] The January average is comparable to temperatures expected for May and September in the major cities of northern Europe.[69]

The maximum of precipitation occurs in autumn, coinciding with the time of the year when cold drop (gota fría) episodes of heavy rainfall—associated to cut-off low pressure systems at high altitude—[70] are common along the Western mediterranean coast.[71] The year-on-year variability in precipitation may be, however, considerable,[71] as exemplified by large floods in 1957 and 2024, which both occurred in the month of October. Snowfall almost does not occur at all; the most recent occasion snow accumulated on the ground was on 11 January 1960.[72]

Valencia, on average, has around 2,733 sunshine hours per year, from 152 in December (average of 5 hours of sunshine duration a day) to 308 in July (average around 10 hours of sunshine duration a day). The average temperature of the sea is 14–15 °C (57–59 °F) in winter and 25–26 °C (77–79 °F) in summer.[73][74] Average annual relative humidity is around 66%.[75]

| Climate data for Valencia (normals and extremes 1991-2020), altitude: 11 m.a.s.l. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.6 (79.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

42.0 (107.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

40.3 (104.5) |

43.0 (109.4) |

38.4 (101.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.8 (62.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

18.6 (65.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.5 (72.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

8.3 (46.9) |

14.2 (57.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

1.2 (34.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39 (1.5) |

30 (1.2) |

40 (1.6) |

33 (1.3) |

36 (1.4) |

26 (1.0) |

7 (0.3) |

15 (0.6) |

70 (2.8) |

63 (2.5) |

52 (2.0) |

48 (1.9) |

459 (18.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1mm) | 3.9 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 44.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65 | 64 | 64 | 62 | 66 | 66 | 68 | 68 | 67 | 68 | 66 | 66 | 66 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 174 | 181 | 217 | 237 | 267 | 282 | 313 | 288 | 237 | 208 | 171 | 158 | 2,733 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorologia (AEMET OpenData)[76] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Valencia (4 km [2 mi] from sea, altitude: 11 m.a.s.l., averages 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.7 (85.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.9 (53.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

33 (1.3) |

38 (1.5) |

39 (1.5) |

22 (0.9) |

8 (0.3) |

20 (0.8) |

70 (2.8) |

77 (3.0) |

47 (1.9) |

48 (1.9) |

475 (18.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 46.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64 | 64 | 63 | 62 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 65 | 65 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 171 | 171 | 215 | 234 | 259 | 276 | 315 | 288 | 235 | 202 | 167 | 155 | 2,696 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[77][78] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1842 | 66,355 | — |

| 1857 | 106,435 | +60.4% |

| 1860 | 107,703 | +1.2% |

| 1877 | 142,063 | +31.9% |

| 1887 | 168,740 | +18.8% |

| 1897 | 203,958 | +20.9% |

| 1900 | 215,687 | +5.8% |

| 1910 | 233,018 | +8.0% |

| 1920 | 247,281 | +6.1% |

| 1930 | 315,816 | +27.7% |

| 1940 | 454,654 | +44.0% |

| 1950 | 503,886 | +10.8% |

| 1960 | 501,777 | −0.4% |

| 1970 | 648,003 | +29.1% |

| 1981 | 744,748 | +14.9% |

| 1991 | 752,909 | +1.1% |

| 2001 | 738,441 | −1.9% |

| 2011 | 792,054 | +7.3% |

| 2021 | 788,842 | −0.4% |

| Source: National Statistics Institute[79] | ||

The third largest city in Spain and the 24th most populous municipality in the European Union, Valencia had a population of 809,267[80] within its administrative limits on a land area of 134.6 km2 (52 sq mi) in 2009. The urban area of Valencia extending beyond the administrative city limits has a population of between 1,564,145[81][82] and 1,595,000.[3]

According to the Valencia city hall[7] and Spanish Ministry of Development, the metropolis within the Horta of Valencia has a population of 1,567,118 in an area of 628.81 km2 (242.78 sq mi).[6] From 2001 to 2011, there was a population increase of 14.1%, amounting to 191,842 people.[83]

| Division of the metropolis Huerta de Valencia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comarca | Population (2019)[84] | Area | Density |

| Ciudad de Valencia | 801 545 | 134,7 km² | 5853 /km² |

| Huerta Oeste (western zone) | 359 337 | 187,6 km² | 1982 /km² |

| Huerta Norte (north zone) | 228 424 | 140,4 km² | 1627 /km² |

| Huerta Sur (south zone) | 178 118 | 166,2 km² | 1071 /km² |

| Total: | 1 567 118 | 631,9 km² | 2480 /km² |

The metropolitan area had a population of 1,770,742 in 2010 according to citypopulation.de,[85] 2,300,000 in 2015 according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development,[86] 2,513,965 in 2017 according to the World Gazetteer,[87] and 2,522,383 in 2017 according to Eurostat.[2]

Between 2007 and 2008, there was a 14% increase in the foreign-born population, with the largest numeric increases by country being from Bolivia, Romania, and Italy. This growth in the foreign born population, which rose from 1.5% in 2000[88] to 9.1% in 2009,[89] has also occurred in the two larger cities of Madrid and Barcelona.[90] The main countries of origin in those cases were Romania, the United Kingdom, and Bulgaria.[91]

Economy

editValencia enjoyed strong economic growth before the Great Recession of 2008, much of it spurred by tourism and construction,[citation needed] with concurrent development and expansion of telecommunications and transport. The city's economy is service-oriented, as nearly 84% of the working population is employed in service sector occupations.[citation needed] However, the city still maintains an important industrial base, with 8.5% of the population employed in this sector. Growth has recently improved in the manufacturing sector, mainly automobile assembly; Ford Valencia Body and Assembly lies in the municipality of Almussafes.[92] Agricultural activity still occurs but is of relatively minor importance, with only 1.9% of the working population working in agriculture and 3,973 ha (9,820 acres) of farmland (mostly orchards and citrus groves).

Since the onset of the Great Recession, Valencia had experienced a growing unemployment rate, increased government debt, and other issues, and severe spending cuts were introduced by the city government. However, in 2009, Valencia was designated "the 29th fastest-improving European city".[93] Its influence in commerce, education, entertainment, media, fashion, science and the arts contributes to its status as one of the world's "Gamma" rank global cities.[9]

The city is the seat of one of the four stock exchanges in Spain, the Bolsa de Valencia, part of Bolsas y Mercados Españoles (BME), owned by SIX Group.[94]

The Valencia metropolitan area had a GDP amounting to $52.7 billion, and $28,141 per capita.[95]

In 2021, the European Investment Bank (EIB) provided a €27 million loan to Sociedad Anónima Municipal Actuaciones Urbanas de Valencia (AUMSA) to support affordable public rental housing projects, which included building 323 new units and renovating four existing ones, expanding AUMSA's housing stock by more than 50%.[96][97]

Port

editValencia's port is the biggest on the Mediterranean western coast,[98] the first in Spain in container traffic as of 2008[update][99] and the second in Spain[100] in total traffic, handling 20% of Spain's exports.[101] The main exports are foodstuffs and beverages. Other exports include oranges, furniture, ceramic tiles, fans, textiles and iron products. Valencia's manufacturing sector focuses on metallurgy, chemicals, textiles, shipbuilding and brewing. Small and medium-sized industries are an important part of the local economy, and before the current crisis,[when?] unemployment was lower than the Spanish average.

Valencia's port underwent radical changes to accommodate the 32nd America's Cup in 2007. It was divided into two parts—one was unchanged while the other section was modified for America's Cup festivities. The two sections remain divided by a wall that projects far into the water to maintain clean water for America's Cup events.

Transport

editPublic transport is provided by Ferrocarrils de la Generalitat Valenciana (FGV), which operates the Metrovalencia (rapid transit, tram) and other rail and bus services. The Estació del Nord (North Station) is the major railway terminus in Valencia. A second station, the Estació de València-Joaquín Sorolla, has been built on land adjacent to this terminus to accommodate high speed AVE trains to and from Madrid, Barcelona, Seville and Alicante. Valencia Airport is situated 9 km (5.6 mi) west of the city centre, and Alicante–Elche Airport is approximately 133 km (83 mi) south of the city centre.

A bicycle-sharing system named Valenbisi is available to both visitors and residents. As of 13 October 2012, the system had 2750 bikes distributed over 250 stations throughout the city.[102]

The average amount of time people spend on public transit in Valencia on a weekday is 44 minutes. 6% of public transit riders ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 10 minutes, while 9% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 5.9 km (3.7 mi), while 8% travel for over 12 km (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[103]

Tourism

editStarting in the mid-1990s, Valencia, formerly an industrial centre, saw rapid development that expanded its cultural and tourism possibilities, and transformed it into a newly vibrant city. Many local landmarks were restored, including the medieval Torres de Serranos and Quart Towers and the Monasterio de San Miguel de los Reyes, which now holds a conservation library. Whole sections of the old city, for example the Carmen Quarter, have been extensively renovated. The Passeig Marítim, a 4 km (2 mi) long palm tree-lined beach promenade, was constructed along the beaches of the north side of the port (Platja de Les Arenes, Platja del Cabanyal and Platja de la Malva-rosa).

Valencia boasts a highly active and diverse nightlife, with bars, dance bars, beach bars and nightclubs staying open well past midnight.[104] The city has numerous convention centres and venues for trade events, among them the Institución Ferial de Valencia and the Palau de Congressos (Conference Palace), and several five-star hotels to accommodate business travelers.

In its long history, Valencia has acquired many local traditions and festivals, among them the Falles, which was declared a Celebration of International Tourist Interest (Festes d'Interés Turístic Internacional) on 25 January 1965 and an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO on 30 November 2016, and the Water Tribunal of Valencia (Tribunal de les Aigües de València), which was declared an intangible cultural heritage in 2009. In addition to these, Valencia has hosted world-class events that helped shape the city's reputation and put it in the international spotlight, such as the Regional Exhibition of 1909, the 32nd and the 33rd America's Cup competitions, the European Grand Prix of Formula One auto racing, the former Valencia Open tennis tournament, and the Global Champions Tour of equestrian sports. The final round of the MotoGP Championship is held annually at the Circuit de la Comunitat Valenciana.

The 2007 America's Cup yachting races were held at Valencia in June and July 2007 and attracted huge crowds. The Louis Vuitton stage drew 1,044,373 visitors and the America's Cup match drew 466,010 visitors to the event.[105]

In October 2021, Valencia was shortlisted for the European Commission's 2022 European Capital of Smart Tourism award, along with Bordeaux, Copenhagen, Dublin, Florence, Ljubljana, and Palma de Mallorca.[106]

Government and administration

editValencia is a municipality, the basic local administrative division in Spain. The ayuntamiento (known as the Consell Municipal de València in the case of Valencia) is the body charged with the municipal government and administration,[107] and is formed by 33 elected municipal councillors. In 2015, Joan Ribó became the first mayor who did not belong to the People's Party (PP) since 1991, renewing his term for a second mandate following the 2019 election.[108] The last municipal election took place on 28 May 2023. María José Catalá of the PP replaced Ribó.

Culture

editValencia is known internationally for the Falles (Les Falles), a local festival held in March, as well as for paella valenciana, traditional Valencian ceramics, craftsmanship in traditional dress, and the architecture of the City of Arts and Sciences, designed by Santiago Calatrava and Félix Candela.

There are also a number of well-preserved traditional Catholic festivities throughout the year, like those of the Holy Week, which are considered some of the most colourful in Spain.[109]

Valencia used to be the place of the Formula One European Grand Prix, first hosting the event on 24 August 2008, but was dropped later at the beginning of the 2013 Formula 1 season. However, Valencia still holds the annual Moto GP race at the Circuit Ricardo Tormo, usually the last race of the season, in November.

The University of Valencia (officially Universitat de València Estudi General), founded in 1499, is one of the oldest surviving universities in Spain and the oldest in the Valencian Community. It was listed as one of the four leading Spanish universities in the 2011 Shanghai Academic Ranking of World Universities.

In 2012, Boston's Berklee College of Music opened a satellite campus at the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia, their first and only international campus outside the U.S.[110] Since 2003, Valencia has also hosted the music courses of Musikeon, the leading musical institution in the Spanish-speaking world.

Food

editValencia is known for its gastronomic culture. The paella, a simmered rice dish with meat (usually chicken or rabbit) or seafood, was born in Valencia. Other traditional dishes of Valencian gastronomy include fideuà, arròs a banda, arròs negre (black rice), fartons, bunyols, Spanish omelette, pinchos or tapas and calamares (squid).

Valencia was also the birthplace of the cold xufa beverage known as orxata, popular in many parts of the world, including the Americas.

Languages

editValencian and Spanish are the official languages. Spanish is currently the predominant language in the city proper.[111] Valencia proper and its surrounding metropolitan area are—along with the Alicante area—the traditionally Valencian-speaking territories of the Valencian Community where the Valencian language is less spoken and read.[112] According to a 2019 survey commissioned by the local government, 76% of the population use only Spanish in their daily life, 1.3% use only the Valencian language, while 17.6% of the population use both languages.[113] However, vis-à-vis the education system and according to the 1983 regional Law on the Use and Teaching of the Valencian Language, the municipality of Valencia is included within the territory of Valencian linguistic predominance.[114] In 1993, the municipal government agreed to use exclusively Valencian for the plaques that serve as street signs.[115]

Festivals

edit- Falles

Every year, the five days and nights from 15 to 19 March, called Falles, are a continual festival in Valencia; beginning on 1 March, the popular pyrotechnic events called mascletàes start every day at 2:00 pm. The Falles (Fallas in Spanish) is an enduring tradition in Valencia and other towns in the Valencian Community,[116] where it has become an important tourist attraction. The festival started being celebrated in the 18th century,[117] and came to be celebrated on the night of the feast day of Saint Joseph, the patron saint of carpenters, with the burning of waste planks of wood from their workshops, as well as worn-out wooden objects brought by people in the neighborhood.[118]

This tradition continued to evolve, and eventually the parots were dressed with clothing to look like people—these were the first ninots, with features identifiable as being those of a well-known person from the neighborhood often added as well. In 1901 the city inaugurated the awarding of prizes for the best Falles monuments,[117] and neighborhood groups still rival with each other to make the most impressive creations.[119] Their intricate assemblages, on top of pedestals for better visibility, depict famous personalities and topical subjects of the past year, presenting humorous and often satirical commentary on them.

On the night of 19 March, Valencians burn all the Falles in an event called "La Cremà".

- Holy Week

The Setmana or Semana Santa Marinera, as the Holy Week is known in the city, was declared "Festival of National Tourist Interest" by 2012.[120]

Main sights

editMajor monuments include Valencia Cathedral, the Torres de Serrans, the Torres de Quart (ca:Torres de Quart), the Lonja de la Seda (declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996), and the Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències (City of Arts and Sciences), an entertainment-based cultural and architectural complex designed by Santiago Calatrava and Félix Candela.[121] The Museu de Belles Arts de València houses a large collection of paintings from the 14th to the 18th centuries, including works by Velázquez, El Greco, and Goya, as well as an important series of engravings by Piranesi.[122] The Institut Valencià d'Art Modern (Valencian Institute of Modern Art) houses both permanent collections and temporary exhibitions of contemporary art and photography.[123]

Architecture

editThe ancient winding streets of the Barrio del Carmen contain buildings dating to Roman and Arab times. The Cathedral and its bell tower El Miguelete, built between the 13th and 15th centuries, are primarily of Valencian Gothic style but contains elements of Baroque and Romanesque architecture. Beside the cathedral is the Gothic Basilica of the Virgin (Basílica De La Mare de Déu dels Desamparats). The 15th-century Serrans and Quart towers are part of what was once the wall surrounding the city.

UNESCO has recognised the Silk Exchange market (La Llotja de la Seda), erected in early Valencian Gothic style, as a World Heritage Site.[124] The Central Market (Mercat Central) in Valencian Art Nouveau style, is one of the largest in Europe. The main railway station Estació Del Nord is built in Valencian Art Nouveau (a Spanish version of Art Nouveau) style.

World-renowned (and city-born) architect Santiago Calatrava produced the futuristic City of Arts and Sciences (Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències), which contains an opera house/performing arts centre, a science museum, an IMAX cinema/planetarium, an oceanographic park and other structures such as a long covered walkway and restaurants. Calatrava is also responsible for the bridge named after him in the centre of the city. The Palau de la Música de València (Music Palace) is another noteworthy example of modern architecture in Valencia.

-

The gothic courtyard of the Palace of the Admiral of Aragon (Palau de l'Almirall)

-

Convento de Santo Domingo (1300-1640)

-

Llotja de la Seda (Silk Exchange, interior)

-

Mercat de Colon in Valencian Art Nouveau style

-

Mercat Central (Central Market), in Valencian Art Nouveau style

-

One of the few arch-bridges that links the cathedral with neighboring buildings. This one built in 1666.

-

Monastery of San Miguel de los Reyes built between 1548 and 1763

-

L'Hemisfèric (IMAX Dome cinema) and Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia

-

Assut de l'Or Bridge and L'Àgora behind.

-

Sant Joan de l'Hospital church built in 1316 (except for a Baroque chapel)

-

Mudéjar (Christian) baths Banys de l'Almirall (1313-1320)

-

The Museum of Fine Arts of Valencia, is the museum with the second largest amount of paintings in Spain,[125][126] after Prado Museum

Cathedral

editThe Valencia Cathedral was called Iglesia Major in the early days of the Reconquista, then Iglesia de la Seu (Seu is from the Latin sedes, i.e., (archiepiscopal) See), and by virtue of the papal concession of 16 October 1866, it was called the Basílica Metropolitana. It is situated in the centre of the ancient Roman city where some believe the temple of Diana stood.[citation needed] In Gothic times, it seems to have been dedicated to the Holy Saviour; the Cid dedicated it to the Blessed Virgin; King James I of Aragon did likewise, leaving in the main chapel the image of the Blessed Virgin, which he carried with him and is reputed to be the one now preserved in the sacristy. The Moorish mosque, which had been converted into a Christian Church by the conqueror, was deemed unworthy of the title of the cathedral of Valencia, and in 1262 Bishop Andrés de Albalat laid the cornerstone of the new Gothic building, with three naves; these reach only to the choir of the present building. Bishop Vidal de Blanes built the chapter hall, and James I added the tower, called El Miguelete in Castilian Spanish or Torre del Micalet in the Valencian language because it was blessed on St. Michael's day in 1418.[citation needed] The tower is about 58 metres (190 feet) high and is topped with a belfry (1660–1736).

In the 15th century the dome was added and the naves extended back of the choir, uniting the building to the tower and forming a main entrance. Archbishop Luis Alfonso de los Cameros began the building of the main chapel in 1674; the walls were decorated with marbles and bronzes in the Baroque style of that period. At the beginning of the 18th century, the German Conrad Rudolphus built the façade of the main entrance. The other two doors lead into the transept; one, that of the Apostles in pure pointed Gothic, dates from the 14th century, the other is that of the Palau. The additions made to the back of the cathedral detract from its height. The 18th-century restoration rounded the pointed arches, covered the Gothic columns with Corinthian pillars, and redecorated the walls.

The dome has no lantern, its plain ceiling being pierced by two large side windows. There are four chapels on either side, besides that at the end and those that open into the choir, the transept, and the sanctuary. It contains many paintings by eminent artists. A silver reredos, which was behind the altar, was carried away in the war of 1808, and converted into coin to meet the expenses of the campaign. There are two paintings by Francisco de Goya in the San Francesco chapel. Behind the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament is a small Renaissance chapel built by Calixtus III. Beside the cathedral is the chapel dedicated to the Our Lady of the Forsaken (Mare de Déu dels Desemparats).

The Tribunal de les Aigües (Water Court), a court dating from Moorish times that hears and mediates in matters relating to irrigation water, sits at noon every Thursday outside the Porta dels Apostols (Portal of the Apostles).[127]

Hospital

editIn 1409, a hospital was founded and placed under the patronage of Santa Maria dels Innocents; to this was attached a confraternity devoted to recovering the bodies of the unfriended dead in the city and within a radius of 5 km (3.1 mi) around it. At the end of the 15th century this confraternity separated from the hospital, and continued its work under the name of "Cofradia para el ámparo de los desamparados". King Philip IV of Spain and the Duke of Arcos suggested the building of the new chapel, and in 1647 the Viceroy, Conde de Oropesa, who had been preserved from the bubonic plague, insisted on carrying out their project. The Blessed Virgin was proclaimed patroness of the city under the title of Virgen de los desamparados (Virgin of the Forsaken), and Archbishop Pedro de Urbina, on 31 June 1652, laid the cornerstone of the new chapel of this name. The archiepiscopal palace, a grain market in the time of the Moors, is simple in design, with an inside cloister and achapel. In 1357, the arch that connects it with the cathedral was built. Inside the council chamber are preserved the portraits of all the prelates of Valencia.

Medieval churches

edit- Sant Joan del Mercat – Gothic parish church dedicated to John the Baptist and Evangelist, rebuilt in the Baroque style after a 1598 fire. The interior ceilings were frescoed by Palomino.

- Sant Nicolau

- Santa Catalina

- Sant Esteve

El Temple (the Temple), the ancient church of the Knights Templar, which passed into the hands of the Order of Montesa and was rebuilt in the reigns of Ferdinand VI and Charles III; the former convent of the Dominicans, at one time the headquarters of the Capitan General, the cloister of which has a Gothic wing and chapter room, large columns imitating palm trees; the Colegio del Corpus Christi, which is devoted to the Blessed Sacrament, and in which perpetual adoration is carried on; the Jesuit college, which was destroyed in 1868 by the revolutionary Committee of the Popular Front, but later rebuilt; and the Colegio de San Juan (also of the Society), the former college of the nobles, now a provincial institute for secondary instruction.

Squares and gardens

editThe largest plaza in Valencia is the Plaça del Ajuntament; it is home to the City Hall (Ajuntament) on its western side and the central post office (Edifici de Correus) on its eastern side, a cinema that shows classic movies, and many restaurants and bars. The plaza is triangular in shape, with a large cement lot at the southern end, normally surrounded by flower vendors. It serves as ground zero during the Les Falles when the fireworks of the Mascletà can be heard every afternoon. There is a large fountain at the northern end.

The Plaça de la Mare de Déu contains the Basilica of the Virgin and the Turia fountain, and is a popular spot for locals and tourists. Around the corner is the Plaza de la Reina, with the cathedral, orange trees, and many bars and restaurants.

The Turia River was diverted in the 1960s, after severe flooding, and the old riverbed is now the Turia gardens, which contain a children's playground, a fountain, and sports fields. The Palau de la Música is adjacent to the Turia gardens and the City of Arts and Sciences lies at one end. The Valencia Bioparc is a zoo, also located in the Turia riverbed.

Other gardens in Valencia include:

- The Jardíns de Monfort (es:Jardines de Monforte)

- The Botanical Garden of Valencia (Jardí Botànic)

- The Jardins del Real or Jardins de Vivers (Del Real Gardens) are located in the Pla del Real district, on just the former site of the Del Real Palace.[128]

Museums

edit- Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències (City of Arts and Sciences). Designed by the Valencian architect Santiago Calatrava, it is situated in the former Túria river-bed and comprises the following monuments:

- Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía, a flamboyant opera and music palace with four halls and a total area of 37,000 m2 (398,000 sq ft).

- L'Oceanogràfic, the largest aquarium in Europe, with a variety of ocean beings from different environments: from the Mediterranean, fishes from the ocean and reef inhabitants, sharks, mackerel swarms, dolphinarium, inhabitants of the polar regions (belugas, walruses, penguins), coast inhabitants (sea lions, etc. L'Oceanogràfic exhibits also smaller animals as coral, jellyfish, sea anemones, etc.

- El Museu de les Ciències Príncipe Felipe, an interactive museum of science but resembling the skeleton of a whale. It has an area of around 40,000 square metres (430,556 square feet) across three floors.

- L'Hemisfèric, an IMAX cinema (es:L'Hemisfèric)

- Museu de Prehistòria de València (Prehistory Museum of Valencia)

- Museu Valencià d'Etnologia (Valencian Museum of Ethnology)

- Blasco Ibáñez House Museum

- Institut Valencià d'Art Modern - IVAM – Centre Julio González (Valencian Institute of Modern Art)

- Museu de Belles Arts de València (Museum of Fine Arts of Valencia)

- Museu Faller (Falles Museum)

- Museu d'Història de València (Valencia History Museum)

- L'Almoina Museum (Centre Arqueològic de l'Almoina), located near the Cathedral

- Natural Science Museum of Valencia, located at Jardins del Real

- Museu Taurí de València (Bullfighting Museum)

- MuVIM – Museu Valencià de la Il·lustració i la Modernitat (Valencian Museum of Enlightenment and Modernity)

- González Martí National Museum of Ceramics and Decorative Arts, housed in the Palace of the Marqués de Dos Aguas

- Computer Museum, located within Technical School of Computer Engineering in Technical University of Valencia[130]

Sport

edit| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valencia CF | La Liga | Football | Mestalla | 1919 | 49,000 |

| Levante UD | La Liga | Football | Estadi Ciutat de València | 1909 | 25,354 |

| Valencia CF Mestalla | Segunda Federación | Football | Estadi Antonio Puchades | 1944 | 4,000 |

| Valencia Basket Club | ACB | Basketball | Pavelló Municipal Font de Sant Lluís | 1986 | 9,000 |

| Valencia Giants | LNFA | American football | Instalacions polideportives del Saler | 2003 | |

| Valencia Firebats | LNFA | American football | Estadi Municipal Jardí del Turia | 1993 | 500 |

| Valencia FS | Tercera División | Futsal | Sant Isidre | 1983 | 500 |

| Valencia Huracanes | Euro XIII | Rugby League | Estadio El Pantano de Villajoyosa | 2019 | 3,000 |

| Les Abelles | División de Honor B | Rugby Union | Poliesportiu Quatre carreres | 1971 | 500 |

| CAU Rugby Valencia | División de Honor B | Rugby Union | Camp del Riu Túria | 1973 | 750 |

| Rugby Club Valencia | División de Honor B | Rugby Union | Poliesportiu Quatre carreres | 1966 | 500 |

Football

editValencia is also internationally famous for its football club, Valencia CF, one of the most successful clubs in Europe and La Liga, winning the Spanish league a total of six times including in 2002 and 2004 (the year it also won the UEFA Cup), and was a UEFA Champions League runner-up in 2000 and 2001. The club is currently owned by Peter Lim, a Singaporean businessman who bought the club in 2014. The team's stadium is the Mestalla, which can host up to 49,000 fans. The club's city rival, Levante UD, plays its home games at Estadi Ciutat de València.

American football

editValencia is the only city in Spain with two American football teams in LNFA Serie A, the national first division: Valencia Firebats and Valencia Giants. The Firebats have been national champions four times and have represented Valencia and Spain in the European playoffs since 2005. Both teams share the Jardín del Turia stadium.

Motor sports

editOnce a year between 2008 and 2012 the European Formula One Grand Prix took place in the Valencia Street Circuit. Valencia is among (with Barcelona, Porto and Monte Carlo) the only European cities ever to host Formula One World Championship Grands Prix on public roads in the middle of cities. The final race in 2012 European Grand Prix saw home driver Fernando Alonso win for Ferrari, in spite of starting halfway down the field. The Valencian Community motorcycle Grand Prix (Gran Premi de la Comunitat Valenciana de motociclisme) is part of the Grand Prix motorcycle racing season at the Circuit Ricardo Tormo (also known as Circuit de València), held in November in the nearby town of Cheste. Periodically the Spanish round of the Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters touring car racing Championship (DTM) is held in Valencia.

Rugby League

editValencia is also the home of the Asociación Española de Rugby League, who are the governing body for Rugby league in Spain. The city plays host to a number of clubs playing the sport and to date has hosted all of the country's international home matches.[131] In 2015, Valencia hosted their first match in the Rugby league European Federation C competition, which was a qualifier for the 2017 Rugby League World Cup. Spain won the fixture 40–30.[132]

Districts

edit- Ciutat Vella: La Seu, La Xerea, El Carmen, El Pilar, El Mercat, Sant Francesc

- Eixample: Russafa, El Pla del Remei, Gran Via

- Extramurs: El Botànic, La Roqueta, La Petxina, Arrancapins

- Campanar: Campanar, Les Tendetes, El Calvari, Sant Pau

- La Saïdia: Marxalenes, Morvedre, Trinitat, Tormos, Sant Antoni

- Pla del Real: Exposició, Mestalla, Jaume Roig, Ciutat Universitària

- Olivereta: Nou Moles, Soternes, Tres Forques, La Fontsanta, La Llum

- Patraix: Patraix, Sant Isidre, Vara de Quart, Safranar, Favara

- Jesús: La Raiosa, L'Hort de Senabre, La Creu Coberta, Sant Marcel·lí, Camí Real

- Quatre Carreres: Montolivet, En Corts, Malilla, La Font de Sant Lluís, Na Rovella, La Punta, Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

- Poblats Marítims: El Grau, El Cabanyal, El Canyameral, La Malva-Rosa, Beteró, Natzaret

- Camins del Grau: Aiora, Albors, Creu del Grau, Camí Fondo, Penya-Roja

- Algirós: Illa Perduda, Ciutat Jardí, Amistat, Vega Baixa, La Carrasca

- Benimaclet: Benimaclet, Camí de Vera

- Rascanya: Els Orriols, Torrefiel, Sant Llorenç

- Benicalap: Benicalap, Ciutat Fallera

- Pobles del Nord

- Pobles del Oest

- Pobles del Sud

Other towns within the municipality of Valencia

editThese towns administratively are within districts of Valencia.

- Towns north of Valencia city: Benifaraig, Poble Nou, Carpesa, Cases de Bàrcena, Mauella, Massarrojos, Borbotó

- Towns west of Valencia city: Benimàmet, Beniferri

- Towns south of Valencia city: Forn d'Alcedo, Castellar-l'Oliveral, Pinedo, El Saler, El Palmar, El Perellonet, La Torre

Notable people

editTwin towns – sister cities

editValencia is twinned with:[133]

Valencia also has friendly relations with:[133]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ It was supposedly brought to that church by Emperor Valerian in the 3rd century, after having been brought by St. Peter to Rome from Jerusalem. The Sant Calze (Holy Chalice) is a simple, small stone cup. Its base was added during the medieval period and consists of fine gold, alabaster and gem stones.[56]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ a b "Valencia/València población por municipios y sexo". (Archived 31 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine). Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Population by sex and age groups" Archived 22 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Eurostat, 2017.

- ^ a b c World Urban Areas Archived 3 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine – Demographia, 04.2018

- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b Dirección General de Vivienda y Suelo. "Áreas Urbanas en España, 2021". Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ a b Ajuntament de Valencia. "Padró d'habitants 2020. Municipis de l'Àrea Metropolitana". Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ "History of Valencia". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ a b "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC - Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Districte 1. Ciutat Vella" (PDF). Oficina d'Estadística. Ajuntament de València (in Valencian and Spanish). 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^ Conselleria de turisme de la Comunitat Valenciana, ed. (2010). "Listado de Fiestas de Interés Turístico de La Comunitat Valenciana Declaradas Por La Conselleria de Turisme" (PDF). Retrieved 11 April 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Valencia named top city for expats". The Independent. 5 December 2022. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Liu, Jennifer (December 2022). "This Spanish city is the No. 1 place to live and work abroad―and it's about to get easier to become a digital nomad there". CNBC. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Astin, A. E. (1989). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-521-23448-1. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Galbis, Agustí (19 June 2009). "La ciutat de Valencia i El nom de "Madinat al-Turab"". Del Sit a Jaume I "Bloc en els artículs d'Agustí Galbis (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Generalitat Valenciana (14 February 2017). "DECRET 16/2017, de 10 de febrer, del Consell, pel qual s'aprova el canvi de denominació del municipi de Valencia per la forma exclusiva en valencià de València. [2017/1189]" (PDF) (in Catalan and Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Navarro Castelló, Carlos (19 September 2023). "El PP pasa de la AVL horas después de la reunión con Mazón y acuerda con Vox una denominación bilingüe de Valencia fuera de la normativa: Valéncia". eldiario.es. Archived from the original on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Romero, Víctor (19 September 2023). ""València o Valéncia": PP y Vox desafían a la 'RAE valenciana' y le cambian la tilde a la ciudad". El Confidencial. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Gwillim Law (1999). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3.

- ^ "Valentia (138 a.c. - 711) | Museu d'Història de València". mhv.valencia.es. Archived from the original on 20 April 2024. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ Coscollá Sanz, Vicente (2003). La Valencia musulmana. Carena Editors, S. L. p. 16. ISBN 978-84-87398-75-9. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Torró 2009, p. 159.

- ^ Torró 2009, p. 160.

- ^ Torró 2009, p. 161.

- ^ a b Torró 2009, p. 163.

- ^ Torró 2009, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Torró 2009, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Saénz-Badillos, Ángel. "Valencia", in: Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, Executive Editor Norman A. Stillman. First published online: 2010.

- ^ Torró 2009, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Torró 2009, p. 168.

- ^ Torró 2009, p. 169.

- ^ Guichard, Pierre (2001). Al-Andalus frente a la conquista cristiana: los musulmanes de Valencia, siglos XI-XIII. Universitat de València. p. 176. ISBN 978-84-7030-852-9. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b Franch Benavent, Ricardo (7 June 2016). "La influencia de la seda en la historia y la cultura valenciana". Universitat de València. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Miquel Milian, Laura (2019). "La estructura del primer banco público de Europa: la Taula de Canvi de Barcelona (siglo XV)". Medievalismo (29). Murcia: Editum: 318–319. doi:10.6018/medievalismo.407021. hdl:10201/93080. ISSN 1131-8155. S2CID 213263696. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ González Arévalo 2019, p. 17.

- ^ González Arévalo 2019, p. 19.

- ^ Santamaría 1992, p. 373.

- ^ a b c Pérez García 2019.

- ^ Mayordomo García-Chicote, Francisco (2000). "Los contables de la Taula de Canvis de Valencia (1519-1649). Su formación teórica y práctica". Revista de Contabilidad. 3 (6). Murcia: Editum. ISSN 1138-4891. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ García Martínez 1972, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b c García Martínez 1972, p. 88.

- ^ Meyerson, Mark D. (1991). The Muslims of Valencia in the Age of Fernando and Isabel: between Coexistence and Crusade. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-520-06888-9.

- ^ Norwich, John Jules (2007). The Middle Sea. A History of the Mediterranean. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-7608-2.

- ^ a b Sala, Daniel (8 December 2006). "La demolición de las murallas de la ciudad". Las Provincias. Archived from the original on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Casals Bergés, Quintí (2022). "El Cantonalismo (1873): Notas para un estudio comparado". Aportes: Revista de historia contemporánea. 37 (110): 59–101. ISSN 0213-5868. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ Aguiló Lúcia 1992, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Aguiló Lúcia 1992, p. 62.

- ^ Cristina Vázquez (16 November 2015), "Valencia, capital de la Segunda República española", El País, archived from the original on 18 April 2018, retrieved 17 April 2018

- ^ a b Ventoso, Luis (11 February 2014). "De cómo Cataluña se volvió rica y Galicia, pobre". ABC. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b Cañada Guillen, Sara (4 October 2017). "Riada de 1957 en València: Se cumplen 60 años". Levante-EMV. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "43 muertos, 47 heridos y 0 responsables: el accidente de metro de Valencia es la historia de una tragedia silenciada". LaSexta. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "About the Santo Caliz (Holy Chalice)". Catholicnews.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2006. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Announcement of the election as host city for 33rd America's Cup". Archived from the original on 23 January 2010.

- ^ Puncel Chornet 1999.

- ^ Monrabal, Josep Sorribes (2011). Valencia, 1957-2007: De la riada a la Copa del América (in Spanish). Universitat de València. ISBN 978-84-370-8260-8. Archived from the original on 15 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ a b Clemente Meoro 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Momblanch y Gonzálbez, Francisco de P. (1960). Historia de la Albufera de Valencia. Excmo. Anuntamiento. p. 301. ISBN 9788484840701. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "AEMET IBERIAN CLIMATE ATLAS" (PDF). www.aemet.es. Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ "Evolucion de los climas de Koppen en España: 1951-2020" (PDF). Agencia Estatal de Meteorologia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. (10 July 2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ "Mapa topográfico de España del Instituto Geográfico Nacional". Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Die Klimatypen der Erde Archived 14 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine - Pädagogische Hochschule in Heidelberg

- ^ "València: València - Valores extremos absolutos - Selector - Agencia Estatal de Meteorología - AEMET. Gobierno de España" (in Spanish). AEMET. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ "L'efecte Foehn, fogony o "ponentà"" (in Valencian). VilMeteo (Meteo Villarreal). 5 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ "World Bank". Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ "La gota fría: dónde, cuándo y cómo se produce". Nueva Tribuna. 13 September 2019. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ a b Rivera, Antonio (20 January 2012). "El clima de Valencia". Las Provincias. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Se cumplen 60 años de la última nevada en València". La Vanguardia. 11 January 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Sea temperature in Valencia". Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Rivera, Antonio (18 July 2010). "Temperatura del agua del mar". Las Provincias (in Spanish). Vocento. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ "Valores climatológicos normales. València". Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "AEMET OpeenData". Agencia Estatal de Meteorologia. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ "Valores climatológicos normales". Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Valores Extremos". Agencia Estatal de Meteorologia. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "Changes in the municipalities in the population census since 1842" (in Spanish). National Statistics Institute.

- ^ "Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (National Statistics Institute)". Ine.es. 28 May 2001. Archived from the original on 7 September 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ Eurostat – Larger Urban Zones: Urban Audit.org Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Inici - València". www.valencia.es. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Áreas urbanas +50, Ministerio de Fomento de España Archived 26 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ INEbase. Alteraciones de los municipios, archived from the original on 25 September 2023, retrieved 1 May 2024

- ^ The Principal Agglomerations of the World – Population Statistics and Maps Archived 4 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine – citypopulation.de

- ^ Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Competitive Cities in the Global Economy Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, OECD Territorial Reviews, (OECD Publishing, 2006), Table 1.1

- ^ [1] Archived 3 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine – World Gazetteer, 2017

- ^ "foreign born population in 2001". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Foreign born population in 2008, p7" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Table 1.1 foreign born population". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Population of Valencia 2017". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Global Operations – Spain: Valencia Body and Assembly Archived 20 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Corporate.ford.com

- ^ "Best European business cities". City Mayors. 28 October 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Torralba, Luis A. (12 June 2020). "Bolsa de Valencia, ni valenciana ni española: ya es suiza (como BME)". Valencia Plaza. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Global city GDP 2011". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (15 July 2024). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2023. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5761-5.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "Valenciaport in figures". valenciaport.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Burguera (10 September 2008). "Valencia supera an Algeciras y lidera por primera vez el tráfico de contenedores en España. Las Provincias" (in Spanish). Lasprovincias.es. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "Resumen general del tráfico portuario en febrero | Puerto Bahía de Algeciras Blog". Puertoalgeciras.org. 22 February 1999. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Mckinley, James C. (2 March 2011). "NY Times, 30 July 2008". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Valenbisi's official website". Valenbisi.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ "Valencia Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017. Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "Viva Valencia! Welcome to the European city that never sleeps". Independent.ie. 10 January 2006. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Economic Impact of the 32nd America's Cup Valencia 2007" (PDF). tourisminsights.info. Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Económicas. Retrieved 31 August 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "2022 European Capital of Smart Tourism - Competition winners 2022". European Commission. 2 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Ayuntamiento de Valencia". Ayuntamiento de Valencia. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Joan Ribó, investido de nuevo alcalde de Valencia con el apoyo del PSPV". LaSexta. 15 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Maritime Holy Week". visitvalencia.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Minder, Raphael (15 March 2011). "Berklee to Open a Campus in Spain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ "Institut Valencià d'Estadística". Generalitat Valenciana. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Briz 2004, p. 120.

- ^ Urbina, Sandra (21 September 2019). "Solo el 1,3 % de la ciudadanía habla habitualmente en valenciano". Levante-EMV. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Zabaltza 2017, p. 69.

- ^ García, Hortensia (29 January 2016). "Nuevo nomenclátor de calles en valenciano". Levante-EMV. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ City Council of Valencia (2008). "Fiestas de Valencia". www.fvmp.es. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012.