Clackmannan (/klækˈmænən/ ; Scottish Gaelic: Clach Mhanainn, perhaps meaning "Stone of Manau"), is a small town and civil parish set in the Central Lowlands of Scotland.[3] Situated within the Forth Valley, Clackmannan is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) south-east of Alloa and 3.2 miles (5.1 km) south of Tillicoultry.[4] The town is within the county of Clackmannanshire, of which it was formerly the county town, until Alloa overtook it in size and importance.

Clackmannan

| |

|---|---|

Clackmannan Tolbooth and Main Street (to the right) | |

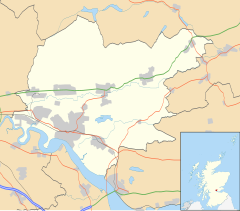

Location within Clackmannanshire | |

| Area | 0.40 sq mi (1.0 km2) |

| Population | 3,260 (2022)[2] |

| • Density | 8,150/sq mi (3,150/km2) |

| OS grid reference | NS911919 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CLACKMANNAN |

| Postcode district | FK10 |

| Dialling code | 01259 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Name and toponymy

editThe name Clackmannan may be of Brittonic origin.[5] The first element is probably *clog, meaning "rock, crag, cliff" (c.f. Welsh clog),[5] and the second is the personal name Manau, from the root man- meaning "projecting.[5] The name of the town has been said to allude to the Stone of Manau[6] or Stone of Mannan,[7][8] a pagan monument that can be seen in the town square beside Clackmannan Tolbooth, which dates from 1592.[9]

A crater on asteroid 253 Mathilde is named after Clackmannan. Because Mathilde is a dark, carbonaceous body, its craters have been named after famous coalfields from across the world.[10] The Clackmannan Group is the name given to a suite of rocks of late Dinantian and Namurian age laid down during the Carboniferous period in the Midland Valley of Scotland.[11]

History

editThe early growth of the town was due in large part to the port which lay on the banks of the tidal stretch of the River Black Devon at its confluence with the River Forth. There are now no visible signs of the port, and Clackmannan now sits over a mile inland from the river. The locals tried in vain to keep their port viable by digging out the silt but to no avail. The silting of Clackmannan's port and the fact that boats could no longer access it meant that the port in Alloa came in to use instead, and this led to an increase in the population of Alloa. Alloa replaced Clackmannan as the county town of Clackmannanshire in 1822.[12] The population of Clackmannan was 1,077 in 1841.[13]

During the 12th century, the area formed part of the lands controlled by the abbots of Cambuskenneth. Later it became associated with the Bruce family, who, during the 14th century, built a strategic tower-house called Clackmannan Tower and in the 16th century built a mansion alongside the tower. The mansion was demolished when local branch of the Bruces died out in 1791, although its stones may have been recycled to build the new parish church in 1815.[12] It still stands above the town according to Historic Scotland, but entry is forbidden (because of subsidence).[14]

The war memorial was designed by Sir Robert Lorimer in 1919.[15]

Archaeology

editHeadland Archaeology completed an excavation of a prehistoric and medieval site at Meadowend Farm, Kennet which lies to the south-east of Clackmannan and was within the corridor for the new road and crossing (the Clackmannanshire Bridge) over the River Forth near Kincardine.[16]

Over 2,000 fragments of prehistoric pottery were recovered from the site, the vast majority from a dense concentration of pits or postholes dated to the middle/late Neolithic period.[17] Several structures were identified on site, the most substantial a large roundhouse with an outer ring-groove and an entrance to the south-east with an extended porch. Two large post-built roundhouses were found, and a third post-built structure contained a hearth-pit, which had been filled with fire-cracked stones and charcoal. It was hoped that radiocarbon dating would enable more precise phasing of the structures.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Placenames Archived 25 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine.(pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ "Mid-2020 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ The Imperial gazetteer of Scotland. 1854. Vol.I. (AAN-GORDON) by Rev. John Marius Wilson. pp.270-271. https://archive.org/stream/imperialgazettee01wils#page/270/mode/2up

- ^ "Measure Distance on a Map". Free Map Tools. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ a b c James, Alan. "The Brittonic Language in the Old North - A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence" (PDF). Scottish Place Name Society. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Rhys, John, Sir (1904). Celtic Britain (3rd ed.). London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 155. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Márkus, Gilbert (2008). "Tracing Emon: Insula Sancti Columbae de Emonia". Innes Review. 55 (1). Edinburgh University Press: 3. doi:10.3366/inr.2004.55.1.1.

- ^ Site Record for Clackmannan, King Robert's Stone Clackmannan StoneDetails Details

- ^ "Clackmannan". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ "Clackmannan". We nae The Stars. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Clackmannan Group". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Clackmannan". Undisciovered Scotland. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ The Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol IV, Caes-Cot (First ed.). London: Charles Knight. 1848. p. 618.

- ^ "Clackmannan Tower". Clackmannanshire Council. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Dictionary of Scottish Architects: Robert Lorimer

- ^ "Excavation: Date January 2006 - April 2006". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Scotland's largest haul of prehistoric pottery found". The Scotsman. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

External links

edit- Media related to Clackmannan at Wikimedia Commons

- Clackmannan Library

- Clackmannan Tower: Clackmannan Towers Official Website