Niagara Falls is a city in Ontario, Canada, adjacent to, and named after, Niagara Falls. As of the 2021 census,[4] the city had a population of 94,415. The city is located on the Niagara Peninsula along the western bank of the Niagara River, which forms part of the Canada–United States border, with the other side being the twin city of Niagara Falls, New York. Niagara Falls is within the Regional Municipality of Niagara and a part of the St. Catharines - Niagara Census Metropolitan Area (CMA).

Niagara Falls | |

|---|---|

| City of Niagara Falls | |

The skyline of Niagara Falls near the edge of the Horseshoe Falls (at left), including the Skylon Tower, the Fallsview Casino, and several high-rise hotels | |

| Nickname(s): The Honeymoon Capital of the World, the Falls | |

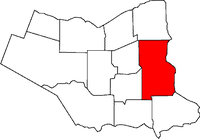

Location of Niagara Falls in the Niagara Region | |

| Coordinates: 43°03′36″N 79°06′24″W / 43.06000°N 79.10667°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Regional municipality | Niagara |

| Settled | 1782 |

| Incorporated | 12 June 1903 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jim Diodati |

| • Governing body | Niagara Falls City Council |

| • MP | Tony Baldinelli |

| • MPP | Wayne Gates |

| Area | |

| • Land | 209.73 km2 (80.98 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 382.68 km2 (147.75 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,397.50 km2 (539.58 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• City (lower-tier) | 94,415 (63rd) |

| • Density | 449.1/km2 (1,163/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 433,604 (13th) |

| • Metro density | 279.3/km2 (723/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Forward Sortation Area | |

| Area code(s) | 905, 289, 365, and 742 |

| GNBC Code | FEDBA[5] |

| Website | www |

Tourism is a major part of the city's economy: its skyline is comprised of multiple high-rise hotels and observation towers that overlook the waterfalls and adjacent parkland. Souvenir shops, arcades, museums, amusement rides, indoor water parks, casinos, theatres and a convention centre are located nearby in the city's large tourist area. Other parts of the city include historic sites from the War of 1812, parks, golf courses, commercial spaces, and residential neighbourhoods.

History

editPrior to European arrival, present day Niagara Falls was populated by Iroquoian-speaking Neutral people but, after attacks from the Haudenosaunee and Seneca, the Neutral people population was severely reduced. The Haudenosaunee people remained in the area until Europeans made first contact in the late 17th century.[6] The Niagara Falls area had some European settlement in the 17th century. Louis Hennepin, a French priest and missionary, is considered to be the first European to visit the area in the 1670s. French colonists settled mostly in Lower Canada, beginning near the Atlantic, and in Quebec and Montreal.

After surveys were completed in 1782 the area was referred to as Township Number 2 as well as Mount Dorchester after Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester (and today is only honoured by Dorchester Road and the community of Dorchester Village).[7] The earliest settlers of Township Number 2 were Philip George Bender (namesake of Bender Street and Bender Hill near Casino Niagara originally from Germany and later New Jersey and Philadelphia[7]) and Thomas McMicken (a Scottish-born British Army veteran).[7] Increased settlement in this area took place during and after the American Revolutionary War, when the British Crown made land grants to Loyalists to help them resettle in Upper Canada and provide some compensation for their losses after the United States became independent. Loyalist Robert Land received 200 acres (81 ha) and was one of the first people of European descent to settle in the Niagara Region. He moved to nearby Hamilton three years later due to the relentless noise of the falls.[8]

In 1791, John Graves Simcoe renamed the town as Stamford after Stamford, Lincolnshire in England[7] but today Stamford is only used for an area northwest of downtown Niagara Falls as well as Stamford Street. During the war of 1812, the battle of Lundy's Lane took place nearby in July 1814.[9] In 1856, the Town of Clifton was incorporated by Ogden Creighton after Clifton, Bristol. The name of the town was changed to Niagara Falls in 1881. In 1882, the community of Drummondville (near the present-day corner of Lundy's Lane and Main Street) was incorporated as the village of Niagara Falls (South). The village was referred to as Niagara Falls South to differentiate it from the town. In 1904, the town and village amalgamated to form the City of Niagara Falls. In 1963, the city amalgamated with the surrounding Stamford Township.[10] In 1970, the Niagara regional government was formed.[11] This resulted in the village of Chippawa, Willoughby Township, and part of Crowland Township being annexed into Niagara Falls.[12]

An internment camp for Germans was set up at The Armoury (now Niagara Military Museum) in Niagara Falls from December 1914 to August 1918.[13]

Black history

editNiagara Falls has had a Black population since at least 1783. Up to 12 African-Americans were a part of the Butler's Rangers, including Richard Pierpoint. When they were disbanded in 1783, they tried to establish themselves through farming nearby, making them among the first Black settlers in the region.[14][15] It is estimated that nearly 10 percent of the Loyalists to settle in the area were Black Loyalists.[16]

Niagara Falls' Black population increased in the following decades, as a destination on the Underground Railroad. In 1856, a British Methodist Episcopal (BME) Church was established for African-Canadian worshipers.[17] The BME Church, Nathaniel Dett Memorial Chapel is now a National Historic Site, remaining in operation into the 21st century.[18][19] Composer, organist, pianist and music professor Nathaniel Dett was born in Niagara Falls in 1882.[20]

In 1886, Burr Plato became one of the first African Canadians to be elected to political office, holding the position of City Councillor of Niagara Falls until 1901.[21][22]

Geography

editNiagara Falls is approximately 130 km (81 mi) by road from Ontario's capital of Toronto, which is across Lake Ontario to the north. The area of the Niagara Region is approximately 1,800 km2 (690 sq mi).

Topography

editThe city is built along the Niagara Falls waterfalls and the Niagara Gorge on the Niagara River, which flows from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario.

Climate

editThe city of Niagara Falls has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa) which is moderated to an extent in all seasons by proximity to bodies of water. Winters are cold, with a January high of −0.4 °C (31.3 °F) and a low of −7.8 °C (18.0 °F).[23] However, temperatures above 0 °C (32.0 °F) are common during winter.[23] The average annual snowfall is 154 centimetres (61 in), in which it can receive lake effect snow from both lakes Erie and Ontario. Summers are warm to hot and humid, with a July high of 27.4 °C (81.3 °F) and a low of 17 °C (62.6 °F).[23] The average annual precipitation is 970.2 millimetres (38 in), which is relatively evenly distributed throughout the year.[citation needed]

Niagara Falls holds the record for the highest temperature recorded in Canada in January, when it reached 22.2 °C (72 °F) on January 26, 1950.

| Climate data for Niagara Falls | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.6 (94.3) |

38.4 (101.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

38.4 (101.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

8.7 (47.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.1 (24.6) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

1.2 (34.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −7.8 (18.0) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

2.2 (36.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.2 (61.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

4.5 (40.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26 (−15) |

−25 (−13) |

−20 (−4) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−24 (−11) |

−26 (−15) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 75.6 (2.98) |

61.8 (2.43) |

61.7 (2.43) |

72.0 (2.83) |

86.8 (3.42) |

80.9 (3.19) |

78.9 (3.11) |

79.2 (3.12) |

98.2 (3.87) |

79.7 (3.14) |

91.8 (3.61) |

81.1 (3.19) |

947.5 (37.30) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 27.8 (1.09) |

29.6 (1.17) |

36.7 (1.44) |

66.0 (2.60) |

85.9 (3.38) |

80.9 (3.19) |

78.9 (3.11) |

79.2 (3.12) |

98.2 (3.87) |

79.7 (3.14) |

81.9 (3.22) |

49.3 (1.94) |

794.0 (31.26) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 47.7 (18.8) |

32.2 (12.7) |

25.0 (9.8) |

6.0 (2.4) |

0.9 (0.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

9.8 (3.9) |

31.8 (12.5) |

153.5 (60.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 14.4 | 11.4 | 11.3 | 12.6 | 13.5 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.4 | 146.6 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.0 | 4.5 | 7.2 | 11.6 | 13.4 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 11.1 | 7.7 | 117.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 9.8 | 7.7 | 5.0 | 1.6 | 0.08 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 6.6 | 33.2 |

| Source 1: Environment Canada (normals 1981–2010, extremes 1981–2006)[24] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Environment Canada (extremes for Niagara Falls 1943−1995)[23] | |||||||||||||

Communities and neighbourhoods

editAlthough more historical and cultural diversity exists, Niagara Falls has 11 communities and 67 neighbourhoods defined by Planning Neighbourhoods and Communities for the City of Niagara Falls.[25]

- Beaverdams

- Hyott

- N.E.C. West

- Nichols

- Shriners

- Warner

- Chippawa

- Bridgewater

- Cummings

- Hunter

- Kingsbridge

- Ussher

- Weinbrenner

- Crowland

- Crowland

- Drummond

- Brookfield

- Caledonia

- Coronation

- Corwin

- Drummond Industrial Basin

- Hennepin

- Leeming

- Merrit

- Miller

- Orchard

- Trillium

- Elgin

- Balmoral

- Central Business District

- Glenview

- Hamilton

- Maple

- Oakes

- Ryerson

- Valleyway

- Grassybrook

- Grassybrook Industrial Basin

- Oakland

- Rexinger

- Northwest

- Carmel

- Kent

- Mulhearn

- Queen Victoria

- Clifton Hill

- Fallsview North

- Fallsview South

- Marineland

- Queen Victoria

- Stamford

- Burdette

- Calaguiro

- Church

- Cullimore

- Gauld

- Ker

- Mitchellson

- Mountain

- N.E.C. East

- Olden

- Pettit

- Portage

- Queensway Gardens

- Rolling Acres

- Thompson

- Wallice

- Westlane

- Garner

- Hodgson

- Lundy

- Munro

- Oakwood

- Royal Manor

- Westlane Industrial Basin

- Willoughby

- Niagara River Parkway

- Willoughby

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1881 | 2,347 | — |

| 1891 | 3,349 | +42.7% |

| 1901 | 4,244 | +26.7% |

| 1911 | 9,248 | +117.9% |

| 1921 | 14,764 | +59.6% |

| 1931 | 19,046 | +29.0% |

| 1941 | 20,371 | +7.0% |

| 1951 | 22,874 | +12.3% |

| 1961 | 22,351 | −2.3% |

| 1971 | 67,163 | +200.5% |

| 1981 | 70,960 | +5.7% |

| 1991 | 75,399 | +6.3% |

| 2001 | 78,815 | +4.5% |

| 2006 | 82,184 | +4.3% |

| 2011 | 82,997 | +1.0% |

| 2016 | 88,071 | +6.1% |

| 2021 | 94,415 | +7.2% |

| Ethnic origin

(>2000 population) |

Population | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | 18,640 | 20.1% | |

| Italian | 15,635 | 16.9% | |

| Canadian | 12,915 | 13.9% | |

| Scottish | 13,930 | 15.0% | |

| Irish | 13,285 | 14.3% | |

| German | 8,890 | 9.6% | |

| French | 7,745 | 8.4% | |

| Polish | 3,905 | 4.2% | |

| Indian | 3,440 | 3.7% | |

| Ukrainian | 3,300 | 3.6% | |

| British Isles, n.o.s. | 3,295 | 3.6% | |

| Dutch | 2,875 | 3.1% | |

| Filipino | 2,725 | 2.9% | |

| Hungarian | 2,280 | 2.5% | |

| Chinese | 2,230 | 2.4% | |

| Source: 2021 Census of Canada | |||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Niagara Falls had a population of 94,415 living in 37,793 of its 39,778 total private dwellings, a change of 7.2% from its 2016 population of 88,071. With a land area of 210.25 km2 (81.18 sq mi), it had a population density of 449.1/km2 (1,163.1/sq mi) in 2021.[4]

At the census metropolitan area (CMA) level in the 2021 census, the St. Catharines - Niagara CMA had a population of 433,604 living in 179,224 of its 190,878 total private dwellings, a change of 6.8% from its 2016 population of 406,074. With a land area of 1,397.09 km2 (539.42 sq mi), it had a population density of 310.4/km2 (803.8/sq mi) in 2021.[26]

As of the 2021 Census,[27] 20.9% of the city's population were visible minorities, 3.5% had Indigenous ancestry, and the remaining 75.6% were White. The largest visible minority groups were South Asian (6.3%), Black (3.1%), Filipino (3.0%), Chinese (2.4%), Latin American (1.6%) and Arab (1.1%).

60.1% of Niagara Falls city residents self-identified with Christian denominations in 2021, down from 74.1% in 2011.[28] 33.2% of residents were Catholic, 13.9% were Protestant, 7.1% were Christians of unspecified denomination, and 2.4% were Christian Orthodox. All other Christian denominations/Christian related traditions made up 3.5%. 30.9% of residents were irreligious or secular, up from 22.5% in 2011. Overall, followers of non-Christian religions/spiritual traditions were 9.0% of the population. The largest of these were Islam (4.1%), Hinduism (2.0%), Sikhism (1.4%) and Buddhism (0.8%)

Economy

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Tourism started in the early 19th century and has been a vital part of the local economy since that time. The falls became known as a natural wonder, in part to their being featured in paintings by prominent American artists of the 19th century such as Albert Bierstadt. Such works were reproduced as lithographs, becoming widely distributed. Niagara Falls marketed itself as a honeymoon destination, describing itself as the "honeymoon capital of the world".[29] Its counterpart in New York also used the moniker.[30] The phrase was most commonly used in brochures in the early twentieth century and declined in usage around the 1960s.[31]

With a plentiful and inexpensive source of hydroelectric power from the waterfalls, many electro-chemical and electro-metallurgical industries located there in the early to mid-20th century. Industry began moving out of the city in the 1970s and 80s because of economic recession and increasing global competition in the manufacturing sector. Tourism increasingly became the city's most important revenue source.

Recent development has been mostly centred on the Clifton Hill and Fallsview areas. The Niagara Falls downtown (Queen Street) is undergoing a major revitalization; the city is encouraging redevelopment of this area as an arts and culture district. The downtown was a major centre for local commerce and night life up until the 1970s, when the Niagara Square Shopping Centre began to draw away crowds and retailers. Since 2006, Historic Niagara has brought art galleries, boutiques, cafés and bistros to the street. Attractions include renovation of the Seneca Theatre.

In 2004, several tourist establishments in Niagara Falls began adding additional fees to bills.[32] These fees have various different names and range in what percentage of the bill they take.[33] The collected money is untraceable and there are no controls over how each establishment spends it. The Ontario government—concerned tourists could be misled into believing the fees were endorsed by the government—warned hotels and restaurants in 2008 not to claim the fee if it was not being remitted to a legitimate non-profit agency that promotes tourism. The practise continues and takes in an estimated $15 million per-year.[32][34] Hotels specifically charge a Municipal Accommodation Tax (MAT) fee, a percentage of which goes to the city. Fees that are present elsewhere only benefit the owners of the business itself, leading to these fees being criticized as deceptive.[33] Some tourists have effectively fought the additional charge, while other businesses have enforced it as mandatory.[35]

Comparison to Niagara Falls, New York

editIn the 20th century, there was a favourable exchange rate when comparing Canadian and U.S. currencies.

Niagara Falls, New York, struggles to compete against Niagara Falls, Ontario; the Canadian side has a greater average annual income, a higher average home price, and lower levels of vacant buildings and blight,[36] as well as a more vibrant economy and better tourism infrastructure.[37] The population of Niagara Falls, New York fell by half from the 1960s to 2012. In contrast, the population of Niagara Falls, Ontario more than tripled.[38]

The Ontario government introduced legal gambling to the local economy in the mid-1990s. Casino Niagara precipitated an economic boom in the late 1990s as numerous luxury hotels and tourist attractions were built, and a second casino, Niagara Fallsview, opened in 2004. Both attracted American tourists due in part to the comparatively less expensive Canadian dollar, and despite the opening of the Seneca Niagara Casino on the American side. When the Canadian and US currencies moved closer to parity in the 2000s, Niagara Falls, Ontario continued to be a popular destination for Americans, while Niagara Falls, New York, experienced a prolonged economic downturn. Ontario's legal drinking age is 19, which attracts potential alcohol consumers from across the border, as the American drinking age is 21.

Arts and culture

editSome cultural areas of Niagara Falls include Queen Street, Main and Ferry Streets, Stamford Centre and Chippawa Square.[39][40] Community centres that are host to cultural activities include the City of Niagara Falls Museums, Niagara Falls Public Libraries, Coronation 50 Plus Recreation Centre, Club Italia and Scotia Bank Convention Centre.

Visual arts

edit- Niagara Falls Art Gallery

- Peterson's Community Gallery

Performing arts

edit- Niagara Falls Centre for the Arts

- Seneca Queen Theatre

History

edit- Niagara Falls History Museum

- Battle Ground Hotel Museum

- Willoughby Historical Museum

- Niagara Military Museum

- Niagara Falls Wedding and Fashion Museum

- Lundy's Lane Historical Society

- Battle of Lundy's Lane Walking Tour

- Historic Drummondville

- Stamford Historic Area

Nature, parks and gardens

edit- Queen Victoria Park

- Rosberg Family Park / Olympic Torch Trail

Festivals and events

edit- Winter Festival of Lights

- Niagara Integrated Film Festival

- Springlicious

- Mount Carmel Fine Art and Music Festival

- Niagara Icewine Festival

- Niagara Woodworking Show

- Greater Niagara Home and Garden Show

- Niagara Night of Art

- Niagara Region Jazz Festival

Conventions and conferences

edit- Niagara Falls Convention Centre

- Sheraton on the Falls Hotel and Conference Centre

Sports teams and leagues

edit| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niagara United | Canadian Soccer League | Soccer | Kalar Sports Park | 2010 |

0 |

| Niagara Falls Canucks | Greater Ontario Junior Hockey League | Ice Hockey | Gale Centre | c. 1971 |

2 |

Attractions

editNotable attractions in Niagara Falls include:

- Table Rock Welcome Centre

- Journey Behind the Falls

- Skylon Tower

- Niagara SkyWheel

- Winter Festival of Lights

- Niagara Parks Butterfly Conservatory

- Niagara Heritage Trail

- Dufferin Islands

- Niagara Parks School of Horticulture

- The Rainbow Carillon, which sounds from the Rainbow Tower

- Clifton Hill, Niagara Falls — Tourist promenade featuring a Ripley's Believe It Or Not Museum, arcades, five haunted houses, four wax museums including a Louis Tussauds Wax Works, and themed restaurants including the Hard Rock Cafe and Rainforest Cafe.

- Marineland — Aquatic theme park

- Casinos — Casino Niagara and Niagara Fallsview Casino Resort

- IMAX Theatre and Daredevil museum

- Fallsview Tourist Area

- Fallsview Indoor Waterpark

- Tower Hotel (Niagara Falls)

Government

editNiagara Falls City Council consists of eight councillors and a mayor. City elections take place every four years with the most recent election held on 24 October 2022. Council is responsible for policy and decision making, monitoring the operation and performance of the city, analysing and approving budgets and determining spending priorities. Due to regulations put forward by the Municipal Elections Act 1996, elections are held on the fourth Monday in October except for religious holidays or if a member of council or if the mayor resigns. Jim Diodati has been the mayor of Niagara Falls since 2010.[41]

As of 2023, the city's fire and emergency services are staffed by 130 firefighters and 104 volunteers.[42] Provincial roads (namely the Queen Elizabeth Way) are patrolled by the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) and the rest by Niagara Regional Police (NRPS) for city streets and general policing or Niagara Parks Police (NPP) on property relating to Niagara Parks Commission. Policing on the Canadian side of bridges (Whirlpool and Rainbow Bridges) are conducted by both Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) operations, but may involve Niagara Regional Police and/or OPP, as well as US agencies.[43] Michigan Central Railway Bridge is an inactive railway bridge; it is closed off by the Canadian Pacific Railways to prevent trespassing but can be accessed by NRPS or CBSA/CBP if required.

Transportation

editHighways

editNiagara Falls is linked to major highways in Canada. The Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW), stretching from Fort Erie to Toronto, passes through Niagara Falls. Highway 420 (along with Niagara Regional Road 420) connect the Rainbow Bridge to the QEW. The Niagara Parkway is a road operated under the Niagara Parks Commission which connects Niagara-on-the-Lake to Fort Erie via Niagara Falls.

Niagara Falls formerly had King's Highways passing through the city. These included:

- The original routing of Highway 3 (later to become Highway 3A), which ended at the Whirlpool Rapids Bridge via River Road

- Highway 8, which ended at the Whirlpool Rapids Bridge via Bridge Street

- Highway 20, which initially ended at the Honeymoon Bridge and later at the Rainbow Bridge via Lundy's Lane and Clifton Hill

Rail

editVia Rail Canada and Amtrak jointly provide service to the Niagara Falls station via their Maple Leaf service between Toronto Union Station and New York Penn Station.

In summer 2009, Go Transit started a pilot project providing weekend and holiday train service from Toronto to Niagara falls from mid June to mid October. These GO Trains run seasonally between Toronto Union Station and Niagara Falls at weekends.[44]

At other times, regular hourly GO train services are provided between Toronto Union and Burlington station, where connecting bus services operate to and from the rail station at Niagara.[45]

As of January 2019, GO Transit offers two-way, weekday commuter service from Niagara Falls station (Ontario) to Union Station (Toronto) as part of the Niagara GO Expansion. The full expansion project is expected to be complete by 2025.[citation needed]

Bus

edit- Coach Canada has daily runs to and from Toronto and Buffalo, New York.

- GO Transit offers daily bus service between Niagara and Burlington GO Station.

- Megabus has daily runs on its route to New York City starting in Toronto.

- Niagara Falls Transit is the public transit operator in the city.

Active transportation

editThe City of Niagara Falls is working toward Bike Friendly designation and providing more resources to encourage active transportation.

Education

editNiagara Falls has one post-secondary institution in the city and another in the Niagara Region. Niagara is served by the District School Board of Niagara and the Niagara Catholic District School Board which operate elementary and secondary schools in the region. There are also numerous private institutions offer alternatives to the traditional education systems.[citation needed]

Post secondary

edit- In the Niagara Region: Brock University in St. Catharines.

- In the City of Niagara Falls: Niagara College, based in Welland, also has campuses in Niagara Falls, Niagara-on-the-Lake and St. Catharines.[46]

- In the city of Niagara Falls: University of Niagara Falls Canada[47]

High schools

edit- A. N. Myer Secondary School

- Westlane Secondary School

- Stamford Collegiate

- Saint Michael Catholic High School

- Saint Paul Catholic High School

Library

editNiagara Falls is also served by Niagara Falls Public Library, a growing library system composed of four branches,[48] with the main branch in the downtown area.[49] It is visited by over 10,000 people weekly. An extensive online database of photographs and artwork is maintained at Historic Niagara Digital Collections.[50]

Media

editNiagara Falls is served by two main local newspapers, three radio stations and a community television channel. All other media is regionally based, as well, from Hamilton and Toronto.

Newspapers

editLocal newspapers are:

- Niagara Falls Review

- Niagara This Week

Due to its proximity to Hamilton and Toronto, local residents have access to the papers like The Hamilton Spectator, the Toronto Star, and the Toronto Sun.

Radio

edit- 91.7 FM - CIXL-FM, "Giant FM" Classic Rock

- 97.7 FM – CHTZ-FM, "97.7 HTZ-FM" Mainstream Rock

- 101.1 FM – CFLZ-FM, "More FM" CHR

- 105.1 FM – CJED-FM, "105.1 The River FM" adult hits

The area is otherwise served by stations from Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo.

Television

edit- Cogeco is the local cable television franchise serving Niagara Falls; the system carries most major channels from Toronto and Buffalo, as well as TVCogeco, a community channel serving Niagara Falls.

- CHCH-DT (UHF channel 15 - virtual channel 11) from Hamilton, Ontario also serves the Niagara Region.

Television stations from Toronto and Buffalo are also widely available. Officially, Niagara Falls is part of the Toronto television market, even though it is directly across the Niagara River from its American twin city, which is part of the Buffalo market.

Notable people

edit- Bruno Agostinelli, professional tennis player[51]

- Ray Barkwill, Canadian national rugby player[52]

- Murda Beatz, Producer and DJ

- Harold Bradley, classical pianist

- James Cameron, film director

- Bill Cupolo, NHL player

- Kevin Dallman, NHL player

- Marty Dallman, NHL player

- Frank Dancevic, professional tennis player

- Sandro DeAngelis, CFL kicker

- Robert Nathaniel Dett, composer born in Drummondville

- Joe Fletcher, referee at FIFA World Cup

- Tre Ford, CFL quarterback

- Tyrell Ford, former CFL and NFL cornerback

- Barbara Frum, CBC broadcaster

- William Giauque, recipient of 1949 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

- Mike Glumac, professional hockey player

- Brian Greenspan, lawyer

- Eddie Greenspan, lawyer

- Bobby Gunn, boxer

- Obs Heximer, NHL player

- Tim Hicks, country singer

- Honeymoon Suite, rock band

- Harold Howard, retired mixed martial artist and UFC fighter

- Jon Klassen, illustrator and children's book author

- Johnathan Kovacevic, NHL player

- Greg Kovacs, bodybuilder

- Judy LaMarsh, second female federal cabinet minister in Canadian history

- Steve Ludzik, NHL player

- Denise Matthews, evangelist, singer

- Bob Manno, NHL player

- John McCall MacBain, philanthropist, billionaire businessman, founder and former CEO of Trader Classified Media

- Nenad Medic, poker player

- Stephan Moccio, musician, arranger, composer

- Tom Moore, trade unionist

- Rick Morocco, ice hockey executive and professional player[53]

- Johnny Mowers, NHL goalie

- Rob Nicholson, former Minister of Justice and Attorney General for Canada

- Terry O'Reilly, NHL player and head coach

- Roula Partheniou, contemporary artist

- Frank Pietrangelo, NHL goalie

- Burr Plato, politician

- deadmau5, musician and DJ[54]

- Isabelle Rezazadeh, DJ and record producer[55]

- Phil Roberto, NHL player

- Gillian Robertson, UFC Fighter

- Derek Sanderson, NHL player

- Jarrod Skalde, NHL player

- Russell Teibert, soccer player

- Steve Terreberry, musician, comedian, and YouTuber

- Frank Thomas, MLB player

- Jay Triano, former NBA head coach

- Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, lawyer and professor; former judge

- Tvangeste, symphonic black metal band formerly based on Kaliningrad, Russia

- Ken Walker, medical columnist using the pen name W. Gifford-Jones, M.D.

- Wave, pop band

- Sherman Zavitz, historian

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Niagara Falls, City Ontario (Census Subdivision)". Census Profile, Canada 2016 Census. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Niagara Falls, City Ontario (Census Subdivision)". Census Profile, Canada 2011 Census. Statistics Canada. 8 February 2012. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "St. Catharines-Niagara Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) with census subdivision (municipal) population breakdowns, land areas and other data". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ a b c "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), Ontario". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "Niagara Falls". Natural Resources Canada. 6 October 2016. Archived from the original on 7 September 2017.

- ^ "Niagara Falls | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Evolution of the City of Niagara Falls - Niagara Falls Museums".

- ^ Hunter, Peter (1958). "The Story of the Land Family". Head-of-the-Lake Historical Society. Archived from the original on 29 December 2011.

- ^ Turner, Wes. "Battle of Lundy's Lane". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ "Evolution of the City of Niagara Falls". Niagara Falls Museums. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ "History of Niagara Region and Regional Council". Niagara Region. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Heritage". Niagara Falls Canada. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Internment Camps in Canada during the First and Second World Wars, Library and Archives Canada". 11 June 2014. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014.

- ^ "Richard Pierpoint". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ "Black History Canada - Niagara Region". www.blackhistorycanada.ca.

- ^ "Black History in Guelph and Wellington County". 4 March 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "The Underground Railroad:Niagara Falls". www.freedomtrail.ca. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "B.M.E Church in Niagara Falls played a role in the 'underground railroad'". CHCH. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "February is Black History Month in Niagara Falls | Niagara Falls Canada". Niagara Falls Canada. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Ezra Schabas; Lotfi Mansouri; Stuart Hamilton; James Neufeld; Robert Popple; Walter Pitman; Holly Higgins Jonas; Michelle Labrèche-Larouche; Carl Morey (17 December 2013). Dundurn Performing Arts Library Bundle. Dundurn. pp. 398–. ISBN 978-1-4597-2401-3.

- ^ "biographies: Burr Plato". www.freedomtrail.ca. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "HistoricPlaces.ca - HistoricPlaces.ca". www.historicplaces.ca.

- ^ a b c d Environment Canada—Canadian Climate Normals 1971-2000 Archived 20 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ "Niagara Falls NPCSH". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. 25 September 2013. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Neighbourhood/Community" (ESRI shapefile). City of Niagara Falls. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "2021 Census Profile-Niagara Falls, City". Statistics Canada.

- ^ "NHS Profile, Niagara Falls, CY, Ontario, 2011". Statistics Canada. 8 May 2013.

- ^ Colombo, John (2001). 1000 Questions About Canada Places, People, Things and Ideas, A Question-and-Answer Book on Canadian Facts and Culture. Dundern Press. p. 102. ISBN 9781459718203.

- ^ Greenburg, Brian; Watts, Linda; Greenwald, Robert; Reavley, Gordon; George, Alice; Beekman, Scott; Bucki, Cecilia; Ciabattri, Mark; Stoner, John; Paino, Troy; Mercier, Laurie; Hunt, Andrew; Holloran, Peter; Cohen, Nancy (2008). Social History of the United States. ABC-CLIO. p. 361. ISBN 9781598841282.

- ^ Lowry, Linda (2016). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism. 22: SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781483368962. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Nicol, John; Seglins, Dave (14 June 2012). "Niagara Falls' Tourist Fees Collected With Little Oversight". CBC News. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014.

- ^ a b Common, David; Vellani, Nelisha; Grundig, Tyana. "A look at the sneaky fees at Canada's biggest tourist spot that some call 'a total cash grab'". CBC News. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ Pellegrini, Jennifer (27 August 2008). "Falls Tourism Operators Criticized for Destination Marketing Fee". Welland Tribune. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014.

- ^ Tomlimson, Asha; Vellani, Nelisha. "Niagara Falls tourism fee called 'ridiculous' as some businesses make it mandatory". CBC News. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ Brady, Jonann (16 September 2008). "Niagara Falls: A Tale of Two Cities". Good Morning America. ABC News.

- ^ Nick Mattera (5 February 2011). "A tale of two cities". Niagara Gazette.

- ^ Mark Byrnes (14 June 2012). "Can Niagara Falls Grow Again?". The Atlantic/CityLab.

- ^ Thomas Austin, Niagara Falls Travel Guide: Sightseeing, Hotel, Restaurant & Shopping Highlights (2014)

- ^ Joel A. Dombrowski, Moon Niagara Falls (2014) excerpt Archived 6 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mitchell, Don. "Jim Diodati re-elected, to serve fourth term as Niagara Falls, Ont. mayor". Global News. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Fire Department". Niagara Falls Canada. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "N.Y. police chief defends border chase cops | CBC News".

- ^ "GOTransit.com - GO Getaway". Archived from the original on 9 November 2015.

- ^ "Niagara Falls/Toronto Bus with Seasonal Rail Service". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Niagara College: How to Find Us". Niagara. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ "Contact - University of Niagara Falls Canada". 12 March 2022.

- ^ Niagara Falls Public Library Archived 17 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ "Victoria Avenue Library" Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Niagara Falls Public Library. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ Historic Niagara Digital Collections Archived 20 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Niagara Falls Public Library. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ "Bruno Agostinelli Jr., former Niagara Falls tennis star, dies at 28". CBC News. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Puchalski, Bernie (21 January 2020). "Barkwill joins Niagara Falls sports wall". BPSN. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Morocco, Rick (Athlete)". Niagara Falls Heritage. Niagara Falls Public Library. 2005. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Dixon, Guy (9 February 2009). "Grand ol' time at the Grammys". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011.

- ^ Law, John (26 August 2015). "Rezz: Niagara's Next Young Gun of EDM". Niagara Falls Review. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017.

Further reading

edit- Mah, Alice. Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline (University of Toronto Press; 2012) 240 pages; comparative study of urban and industrial decline in Niagara Falls (Canada and the United States), Newcastle upon Tyne, Britain, and Ivanovo, Russia.

External links

edit- Official website

- Niagara Falls, Ontario travel guide from Wikivoyage