Climate change is impacting the environment and human population of the United Kingdom (UK). The country's climate is becoming warmer, with drier summers and wetter winters. The frequency and intensity of storms, floods, droughts and heatwaves is increasing, and sea level rise is impacting coastal areas. The UK is also a contributor to climate change, having emitted more greenhouse gas per person than the world average. Climate change is having economic impacts on the UK and presents risks to human health and ecosystems.[1]

The government has committed to reducing emissions by 50% of 1990 levels by 2025 and to net zero by 2050.[2][3] In 2020, the UK set a target of 68% reduction in emissions by 2030 in its commitments in the Paris Agreement.[4] The country phased-out coal power in 2024. Parliament passed Acts related to climate change in 2006 and 2008, the latter representing the first time a government legally mandated a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. The UK Climate Change Programme was established in 2000 and the Climate Change Committee provides policy advice towards mitigation targets. In 2019, Parliament declared a 'climate change emergency'.[5] The UK has been prominent in international cooperation on climate change, including through UN conferences and during its European Union membership.

Climate change has been discussed by British politicians since the late 20th century, but it has attracted greater political, public and media attention in the UK from the 2000s. Public opinion polls show concern amongst the majority of Britons. The British royal family have also prioritised the issue, with King Charles III having been outspoken "about climate change, pollution and deforestation" for the "last 50 years."[6] Various climate change activism initiatives have taken place in the UK.

Greenhouse gas emissions

editIn 2021, net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the United Kingdom (UK) were 427 million tonnes (Mt) carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), 80% of which was carbon dioxide (CO2) itself.[7] Emissions increased by 5% in 2021 with the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, primarily due to the extra road transport.[7] The UK has over time emitted about 3% of the world total human caused CO2, with a current rate under 1%, although the population is less than 1%.[8]

Emissions decreased in the 2010s due to the closure of almost all coal-fired power stations.[9] In 2020 emissions per person were somewhat over 6 tonnes when measured by the international standard production based greenhouse gas inventory,[10] near the global average.[11] But consumption based emissions include GHG due to imports and aviation so are much larger,[12] about 10 tonnes per person per year.[13]

The UK has committed to carbon neutrality by 2050.[14] The target for 2030 is a 68% reduction compared with 1990 levels.[15] The UK has been successful in keeping its economic growth alongside taking climate change action. Since 1990, the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions have reduced by 44% while the economy has grown by around 75% up until 2019.[16] One of the methods of reducing emissions is the UK Emissions Trading Scheme.[17]

Meeting future carbon budgets will require reducing emissions by at least 3% a year. At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference the Prime Minister said the government would not be "lagging on lagging", but in 2022 the opposition said Britain was badly behind in such home insulation.[18] The Committee on Climate Change, an independent body which advises the UK and devolved government, has recommended hundreds of actions to the government,[19] including better energy efficiency, such as in housing.[20][21]Impacts on the natural environment

editTemperature and weather changes

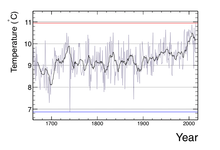

editThe Central England temperature series, recorded since 1659 in the Midlands, shows an observed increase in temperature, consistent with anthropogenic climate change rather than natural climate variability and change.[25] According to the Met Office, climate change will affect the climate of the United Kingdom with warmer and wetter winters and hotter and drier summers. Spanish plumes will continue but bring more intense weather conditions such as hotter summer weather and summer thunderstorms.[26]

By 2014, the United Kingdom's seven warmest and 4 out of its 5 wettest years had occurred between the years of 2000–2014. Higher temperatures increase evaporation and consequently rainfall. In 2014, England recorded its wettest winter in over 250 years with widespread flooding.[27]

In parts of the south east of the UK, the temperature in the hottest days of the year increased by 1 °C per decade in the years 1960–2019. The highest ever recorded temperature in the United Kingdom was recorded in 2022 in Coningsby at 40.3 °C (104.5 °F).[28] In 2020, the chances of reaching a temperature above 40 °C (104 °F) were low, but they are 10 times higher than in a climate without human impact. In modest emissions scenario, by the end of the century, it will happen every 15 years and in high emissions scenario every 3–4 years. Summers with temperatures above 35 °C (95 °F) occur in the UK every 5 years, but will occur almost every other year in the high emission scenario by 2100.[29]

Extreme weather events

editThe Met Office outlines that more frequent and intense extreme weather events will affect the UK due to climate change.[26]

Floods

editDue to increased rainfall from warmer and wetter winters, increased flooding is expected.[26] An interactive map from the UK government shows areas at risk of flooding.[31]

Heat waves

editHeat waves are becoming more intense and more likely in the UK due to climate change.[26][32] Of the UK's top ten hottest days on record, nine have been recorded between 1990 and 2022.[33] The 2022 heatwave resulted in the first code red extreme heat warning in the country, instigating a declaration of national emergency, and causing wildfires and widespread infrastructure damage.[34][35]

Sea level rise

editBetween 1900 and 2022, the UK's sea level rose by 16.5 centimetres (6.5 in). The rate of rise more than doubled between the early 20th and early 21st century to a rate of 3-5.2 millimetres per year.[36] By 2050, it is predicted that around a third of England's coast will be impacted, leading to almost 200,000 homes needing to be abandoned. The most affected regions will be the South West, North West and East Anglia.[37]

Water and drought

editDroughts in the United Kingdom are expected to become more severe.[38][39][40] Water quality in rivers and lakes may decline due to higher temperatures, reduced river flows and increased algal blooms in summer, and increased river flows in winter.[41]

Impacts on ecosystems

editWarming temperatures are impacting wildlife and plant life. Some species' ranges are shifting north, and Scottish alpine plants have declined.[42] With spring coming earlier each year, many plant and animal species are unable to adapt quickly enough.[36] Birds are impacted by climate change, with warm weather species like cattle egrets and purple herons observed breeding in the UK for the first time in the 2010s, while cold-adapted birds like lapwings have declined.[42] More regular droughts also have cumulative implications for many British species and ecosystems.[43] For example, in 2022, Ouse Washes wetlands was at risk of drying out.[43]

Climate change will also impact marine life around the British Isles, including some commercially valuable fish species. The distributions of many fish species are expected to shift, with cold adapted species declining and warm adapted species becoming established.[44]

Impacts on people

editEconomic impacts

editAccording to the Government, the number of households in flood risk will be up to 970,000 homes in the 2020s, up from around 370,000 in January 2012.[45] The effects of flooding and managing flood risk cost the country about £2.2bn a year, compared with the less than £1bn spent on flood protection and management.[46] UK agriculture is also being impacted by drought and weather changes.[47]

In 2020 PricewaterhouseCoopers estimate that Storm Dennis damage to homes, businesses and cars could be between £175m and £225m and Storm Ciara cost up to £200m.[48][49] Friends of the Earth criticised British government of the intended cuts to flood defence spending. The protection against increasing flood risk as a result of climate change requires rising investment. In 2009, the Environment Agency calculated that the UK needs to be spending £20m more compared to 2010 to 2011 as the baseline, each and every year out to 2035, just to keep pace with climate change.[50]

The British government and the economist Nicholas Stern published the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change in 2006. The report states that climate change is the greatest and widest-ranging market failure ever seen, presenting a unique challenge for economics. The Review provides prescriptions including environmental taxes to minimise economic and social disruptions. The Stern Review's main conclusion is that the benefits of strong, early action on climate change far outweigh the costs of not acting.[51] The Review points to the potential impact of climate change on water resources, food production, health, and the environment. According to the Review, without action, the overall costs of climate change will be equivalent to losing at least 5% of global gross domestic product (GDP) each year, now and forever. Including a wider range of risks and impacts could increase this to 20% of GDP or more. The review leads to a simple conclusion: the benefits of strong, early action considerably outweigh the costs.[52]

Climate change made the unusual rainfall in autumn and winter 2023-2024, 10 times more probable and 20% stronger. The rainfall led to "severe damage to homes and infrastructure, power blackouts, travel cancellations, and heavy losses of crops and livestock." The damage to arable crops alone is £1.2 billion, without counting vegetables. Claims for house insurance from weather related disasters increased by more than a third.[53]

Health impacts

editClimate change has significant implications for health, healthcare and health inequality in the UK.[54] The National Health Service describes climate change as a "health emergency", citing the health impacts of floods, storms and heat waves, as well as the increased risk of infectious diseases such as tick-borne encephalitis and vibriosis.[55] It also suggests reduction of greenhouse gas emissions would also reduce deaths from air pollution.[55]

Climate change had made heat waves 30 times more likely in the UK and 3,400 people died from them in the years 2016–2019. Climate change-driven heatwaves in other countries important for crop production may also be more severe, which will have an indirect impact on the UK.[56] UK heat waves have implications for human health and can drive excess deaths, particularly among the elderly.[26] Heavy rainfall intensified by climate change killed at least 20 people in the UK and Ireland in 2023-2024.[53]

Mitigation

editIn 2019, Prime Minister Theresa May announced the UK would strive to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, making the country the first major economy to do so.[57] Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced in 2020 that UK would set a target of 68% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and include this target in its commitments in the Paris Agreement.[4]

Calculations in 2021 indicated that, to give the world a 50% chance of avoiding a temperature rise of 2 degrees or more, the United Kingdom should increase its climate commitments by 17%.[58]: Table 1 For a 95% chance, it should increase the commitments by 58%. To give a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees, the UK should increase its commitments by 97%.[58]

Energy

editUnder Margaret Thatcher, the UK's coal industry was reduced, with subsidies cut and coal miners' union weakened following a significant miners' strike in 1984.[57] In 2015, the government announced all coal-fired power stations would be closed by 2025.[60] In 2021, it brought forward this coal phase-out target to 2024.[61]

Renewable energy in the United Kingdom contributes to production for electricity, heat, and transport.

From the mid-1990s, renewable energy began to play a part in the UK's electricity generation, building on a small hydroelectric capacity. Wind power, which is abundant in the UK, has since become the main source of renewable energy. As of 2022[update], renewable sources generated 41.8% of the electricity produced in the UK;[62] around 6% of total UK energy usage. Q4 2022 statistics are similar, with low carbon electricity generation (which includes nuclear) at 57.9% of total electricity generation (same as Q4 2021).[63]

Wind energy production was 26,000 GWh in Q4 2022 (from 2,300 GWh in Q1 2010), and the installed capacity of 29,000 MW (5,000 in 2010)[64] ranked the UK 6th in the world in 2022.

In 2022, bioenergy comprised 63% of the renewable energy sources utilized in the UK, with wind accounting for the majority of the remaining share at 26%, while heat pumps and solar each contributed approximately 4.4%.[62]

Interest has increased in recent years due to UK and EU targets for reductions in carbon emissions, and government incentives for renewable electricity such as the Renewable Obligation Certificate scheme (ROCs), feed in tariffs (FITs), and Contracts for Difference as well as for renewable heat such as the Renewable Heat Incentive. The 2009 EU Renewables Directive established a target of 15% reduction in total energy consumption in the UK by 2020. The UK is aiming to reach net zero by 2050.[65]Electric vehicles

editPolicies and legislation

editThe Climate Change Programme was launched in 2000 by the Government in response to its commitment agreed at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development.[citation needed]

There are in place national legislation, international agreements and the EU directives. The Climate Change and Sustainable Energy Act 2006 aimed to boost heat and electricity micro-generation installations in the UK, helping to cut emissions and reduce fuel poverty. The Climate Change Act 2008[69] makes it the duty of the Secretary of State to ensure the net UK carbon account for all six Kyoto greenhouse gases for 2050 is at least 80% lower than 1990. It also created the independent Climate Change Committee to advise the government on policies to reach its goals. The Act made the UK the first country to legally mandate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.[57]

These targets have since been expanded on in the UK's Sixth Carbon Budget of 2021, which set the targets of reducing carbon emissions by 78% in relation to 1990 levels by 2035, and reaching net zero emissions by 2050.[70] The Health and Care Act 2022 includes a target of carbon neutrality for the National Health Service by 2040, and an 80% reduction in emissions by 2028-32.[71]

In May 2019, Parliament approved a motion declaring a national climate change emergency. This does not legally compel the government to act, however.[5] The Climate and Ecological Emergency Bill was tabled as an early day motion in September 2020 and received its first reading the same day.[72][73]

The United Kingdom does not have a carbon tax.[74] Instead, various fuel taxes and energy taxes have been implemented over the years, such as the fuel duty escalator (1993)[75] and the Climate Change Levy (2001).[76] The UK was a member of the European Union Emission Trading Scheme until it left the EU. It has since implemented its own carbon trading scheme.[77]

International cooperation

editSince the premiership of Tony Blair, climate change has been a high priority issue in the UK's foreign policy.[78] The UK has raised the issue at meetings of international bodies of which it is a member, including the G8 and United Nations Security Council.[79] The UK was also influential on the climate change policy of the European Union during its membership.[57][79]

British diplomats have been involved in the negotiation of international agreements in United Nations summits.[57] Ahead of the 2009 conference while talks had been stalling, prime minister Gordon Brown launched a manifesto calling for an international agreement that would bring investment into climate change adaptation in developing countries.[80][81] The UK hosted the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, during which the Glasgow Climate Pact was negotiated and agreed.[82] In the lead-up to the conference, Richard Moore said the Secret Intelligence Service had begun monitoring the activities of major polluters to ensure they adhere to their commitments on mitigation[83] and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office said it would put £290m towards climate change initiatives in developing countries.[84]

Policy Instruments

editClimate Change Levy (CCL)

editA Climate Change Levy is a tax on carbon use in industry, commerce and the public sector introduced by the British government in 2001, with the overall aim of promoting carbon efficiency and stimulating investment in low carbon technology.[85] While representing what is classed as a “market-based instrument”,[86] in that it represents an economic incentive to manage carbon usage more effectively, the CCL is not what is understood as market governance. This is because CCL is not representative of the market steering actors in their carbon behaviour, but the government imposing a sanction[87] to govern behaviour, which is constitutive of hierarchical governance.

Climate Change Agreements (CCAs)

editIntroduced at the same time as the CCL, Climate Change Agreements are “negotiated agreements between sector industry organisations and the government”[88] whereby “energy-intensive industries can obtain a 65% discount from the CCL, provided they meet challenging targets for improving their energy efficiency or reducing carbon emissions”.[89] This is an interesting example of governing carbon behaviour in a more indirect fashion. The DECC is still the authoritative body, but these voluntary agreements represent their attempt to create an atmosphere where it is seen as advantageous to business to manage carbon emissions.[90] They have not done this through traditional regulatory controls, in that they have not imposed this rule upon industry. By instead offering businesses incentives to reduce carbon emissions through a tax reduction, they are enhancing the desire of business sectors to make the choice to become more carbon efficient.[91] The DECC asserts its authority over the process by the imposition of penalties if participating industries do not comply with their agreed targets. It represents the government concerning itself with the outcome of the policy, rather than regulating the entire process.[92]

Enhanced Capital Allowances (ECA)

editThis represents a further example of a government implemented, voluntary scheme that shapes the carbon behaviour of businesses, but the actual management of this scheme is delegated to a specialised body, The Carbon Trust. The scheme encourages businesses to invest in low-carbon technology by offering a “100% first-year capital allowances on their spending on qualifying plant and machinery”.[93] Only new equipment is eligible for an ECA – used or second-hand equipment does not qualify. Eligible equipment, and the criteria they have to meet, is published in the Energy Technology List. The criteria are reviewed annually to keep pace with technological progress [94]

The Carbon Trust and the ECA

editBy providing a management service on behalf of the government, The Carbon Trust is actually helping govern a part of the carbon sector in England. Although created by the government in 2001, they are a private company, which means that, arguably, they represent the diminishment of central capacity to fulfil governing tasks.[95] However, if the workings of the scheme and the part The Carbon Trust have to play is examined, then the opposite is true. In this instance DECC involved The Carbon Trust, as a body specialised in energy efficiency, and delegated responsibility to them “to ensure sufficient expertise”[96] is brought to the governing process. It is still the government's decision to delegate such responsibility, and it is their policy that is being enacted. They have simply enlisted the help of an expert body to ensure that their desired outcomes are met.

Emissions trading

editEmissions trading constitutes a massive part of carbon governance in England. While it has been argued that this is an attempt to allow markets to govern carbon emissions by incentivising their proper management[97] and allowing them to be traded and priced by supply and demand, the hierarchical influence of the governmental institutions, the EU and DECC, are still evident and prevent emissions trading in England in its current form being considered market governance. There are two emissions trading systems operating in England at this present moment, and the way in which they are governed is emblematic of the hierarchical nature of carbon governance at the national level.

The UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS)

editThe former UK Emissions Trading Scheme was a voluntary cap-and-trade scheme where participants were allocated an allowance of emissions, which included other GHGs as well as carbon, and if a participating company emitted less than their cap for that year they could trade the remaining allowances. It has now closed to new participants but allowances are still traded. While this may appear as recourse to the market to effectively govern carbon emissions, the fact remains “in order to govern through markets, governments must first create those markets through the exercise of a hierarchical authority”.[98] The UK ETS was created by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), the then responsible government department, and it was the government's ambitious emissions reduction target that “spurred the UK to innovate with” [99] this particular instrument. The Trading Registry for emissions is also run through DECC, exemplifying the government's centralisation of the process and while it was left to businesses to decide how to manage their carbon emissions, and the market to decide the price, it was the governments desire to reach emissions targets and “reduce (the) economic cost”[100] of doing so that was being represented.

A new post-Brexit UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS) came into operation on 1 January 2021 following the UK's departure from the European Union.[101]

EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS)

editIntroduced by the European Commission (EC) and launched in 2005, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme is similar to the UK ETS in the sense that it is a cap-and-trade scheme, but it is mandatory and its participants account for 40% of the EU's total GHG emissions.[102] With regards to the governance of carbon in England, the scheme covers industries responsible for 48% of the UK's total carbon emissions. Because the European Commission, which supersedes the UK government in terms of legislative authority, enacted the system its introduction presents a challenge to the central power of the UK government in terms of carbon management. Rhodes cited “the loss of functions by British government to EU institutions”[103] as evidence of the nation state becoming ‘hollowed out’ and while this system was imposed upon England by an EU body, there is some evidence to suggest that the British government still retains some central authority.

National Allocation Plans (NAPs)

editThese are a calculation of an “overall cap on the total emissions allowed from all the installations covered by the EU ETS” by member states which are submitted to the EC and approved before being allocated to industries by the member states.[104] The presence of the NAP is a strong indication of the authority that the UK government retains over carbon governance. For it is still the UK government that is the delegator of emissions, and it is they who negotiate the UK allowances with the EC. While there has to be agreement from the EC with regards to the proposed NAP, the fact remains that the UK government is the central administrator for emissions and therefore its place in the carbon governance system in this respect has not been diminished.

The Environment Agency and the EU ETS

editA large part of the administrative burden of the EU ETS falls on to The Environment Agency, a “non-departmental public body”[105] who are actually responsible not to DECC, but to DEFRA. Although DECC are the body responsible for implementing the EU ETS into law and for the setting of the overall targets, the Environment Agency issues guidance documents, collates data on the trading of emissions and deals with applications for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Permits, which firms need in order to participate in the scheme. They also administer, on behalf of the EC, the penalties for non-compliance. These facts point towards the government and the EU seeking the expertise of a specialised body in order to fulfil their policy aims. Using The Environment Agency to assist in ensuring that the targets are met and performance of the system is maintained is not a loss of power for the government, but them ensuring that their overall targets are met by a delegation of responsibility.

CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme

editThe CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme is further evidence of the UK government's “recourse to specialised regulatory remits”[106] in order to effectively govern carbon emissions in England. The CRC scheme is a further mandatory cap-and-trade scheme aimed at large public and private sector organisations who account for 10% of the UK's carbon emissions. It seeks to include organisations not covered by the EU ETS.[107] It is again reflective of the UK government's disposition towards employing market mechanisms in order to govern carbon emissions,[108] and it is they who have imposed this legislation on businesses, representing an exercise of central power. However, a large bulk of the implementation of the scheme is carried out by The Environment Agency.

The Environment Agency and the CRC

editThe Environment Agency has a key role to play in the imposition of the scheme. It is responsible for collecting data regarding participating companies’ emissions which it then ranks in a league table “based on participant's changes in energy use against a baseline and not their total emissions”[109] with the hope that carbon efficiency will become a “reputational issue"[110] for those involved. The Environment Agency also hosts the CRC Registry where participants can register details and trade their emissions. It is also responsible for administering any sanctions for non-compliance. This is a classic example of the government using the skills of, in this case, a non-governmental public body in order to administer a policy they have established. Again, it is not an example of the power to govern being taken away from central government as the “enactment of legislation is evident as an explicit assertion of hierarchy”.[111] It is the government who has delegated this responsibility to The Environment Agency, and they remain the ultimate statutory authority for the scheme.

Adaptation

editThe UK Climate Change Risk Assessment sets out the risks facing the UK. It informs the National Adaptation Programme.[112]

The National Adaptation Programme (NAP) seek to create a "climate-ready society" and expects households to adapt to climate change. The NAP outline actions the government and other entities will take to adapt to climate change challenges e.g. in England over a five-year period. They cover aspects such as the natural environment, infrastructure, people and the built environment, business and industry, and local government sectors.[112] NAP3 explains the government's plans to adapt to climate change between 2023-28.[113]

A systematic review in Climatic Change concluded many households in the UK struggled to achieve long-term adaptive capacity.[114] Increased flood risk has implications for the UK's privatised insurance sector and relevant governance of it.[115] The Bank of England has outlined a policy of maintaining financial stability amid climate change impacts on the UK.[116] The town of Happisburgh, where homes are being affected by coastal erosion and sea level rise, is the location of a "Pathfinder" project where owners of homes about to fall into the sea were offered market prices to relocate inland.[37]

The Wildlife Trusts have suggested reintroduction of Eurasian beavers improves resilience of British rivers and wetlands to droughts, create carbon sinks and prevent flooding.[117][118]

Society and culture

editEducation

editIn the United Kingdom, the Teach the Future campaign aims to rapidly repurpose the education system around the climate emergency and ecological crisis;[119] they are cohosted by the UK Student Climate Network and SOS-UK and are in the process of devolving their campaign to Scotland and Northern Ireland from England.

They have three asks of the Government:[120]

- A government commissioned review into how the English formal education system is preparing students for the climate emergency and ecological crisis

- The inclusion of the climate emergency and ecological crisis in English teaching standards and training

- The enactment of an English Climate Emergency Education Act - the first student written bill in history

Public opinion

editBy 2021, YouGov recorded that 72% of Britons believe that climate change is caused by human activity, which had increased from 49% in 2013.[121] According to the Office for National Statistics, as of October 2021, 75% of British adults said that they either very or somewhat worried about climate change, whilst 19% were neither worried or unworried. British women were more likely than men to be worried about the impact of climate change, as were younger compared to older age groups.[122]

Politics

editIn 1989, Margaret Thatcher made two speeches that are considered among the earliest statements by a world leader on climate change.[57]

Climate change has been discussed by members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom; in 2019, Carbon Brief analysed mention of climate change in the UK parliamentary record from Hansard. It found that mention of the "greenhouse effect" and "global warming" had appeared in British parliamentary records since the 1980s, with the term "climate change" used more since the late 1990s. The first mention was by Jestyn Philipps in 1969. It concluded that Labour MPs were the most vocal party on the issue, mentioning climate change 8,463 times, compared to 5,860 by Conservative MPs and 2,426 by Liberal Democrat MPs.[123]

Before 2005 and 2006, climate change received little political attention in the UK.[78] However, between 2006 and 2010, campaigns by environmental non-governmental organization generated attention towards climate change in British media, and it became a bipartisan issue in UK politics.[78] The Climate Change Act 2008 passed with the support of 463 MPs from several political parties, and only 5 against.[57] Under David Cameron, the Conservative Party adopted environmental policies as a means to connect with younger voters, with Cameron's support of the Big Ask campaign being a critical turning point.[57][78] The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition maintained political momentum on climate policy, but criticism from the political right later weakened Cameron's international leadership on the issue.[78] The Conservatives prioritised the issue during the premiership of Boris Johnson.[124]

The Global Warming Policy Foundation is a climate change denialist think tank and lobby group founded by former chancellor Lord Nigel Lawson in 2009.[125][126] Some members of the UK Independence Party have been characterised as deniers and have dismissed climate change risks[127] and the party has opposed climate policies, with some claims within its 2013 energy policy document found to be based on documents from the Global Warming Policy Foundation.[128] The Global Warming Policy Foundation and some members of the Conservative Party shifted to opposing the perceived cost of net zero rather than outright denying the occurrence of climate change in the 2020s.[129][130] Still in 2024, at least thirty Reform UK candidates went beyond mere skepticism about net zero, to actually casting doubt on the validity of human-caused global warming, some employing accusations of "hoaxes" or "scams" by "globalist elites" or "the Illuminati".[131]

Activism and cultural responses

editEnvironmental direct action has occurred in the UK.[132] Camps for Climate Action began in 2006 with the Drax Power Station, until their disbandment in 2011.[133] School strikes took place from the 2010s, and groups such as Extinction Rebellion and Insulate Britain using tactics such as traffic obstruction in protest of climate change issues.[132] Extinction Rebellion was founded by a group of UK activists in 2018, subsequently expanding to other countries and influencing the global climate movement.[134]

In February 2014 during major flooding the Church of England said that it will pull its investments from companies that fail to do enough to fight the "great demon" of climate change and ignore the church's theological, moral and social priorities.[135] In 2007, a London Live Earth concert took place to raise awareness of climate change[136] and in 2019, numerous musicians, record labels and venues in the British music industry formed environmental pressure group Music Declares Emergency to demand mitigation.[137]

Litigation

editThis section needs to be updated. The reason given is: result of cases? which UK cases most notable now?. (September 2024) |

In December 2020, three British citizens, Marina Tricks, Adetola Onamade, Jerry Amokwandoh, and the climate litigation charity, Plan B, announced that they were taking legal action against the UK government for failing to take sufficient action to address the climate and ecological crisis.[138][139] The plaintiffs announced that they will allege that the government's ongoing funding of fossil fuels both in the UK and other countries constitute a violation of their rights to life and to family life, as well as violating the Paris Agreement and the UK Climate Change Act of 2008.[140]

In 2022, it was claimed in McGaughey and Davies v Universities Superannuation Scheme Ltd that the directors of the UK's largest pension fund, USS Ltd had breached their duty to act for proper purposes under the Companies Act 2006 section 171, by failing to have a plan to divest fossil fuels from the fund's portfolio. The claim did not succeed in the High Court,[141] and the claimants appealed to the Court of Appeal, being granted permission for a June 2023 hearing.[142] The case alleges that the right to life must be used to interpret duties in company law, and that because fossil fuels must cease to exist, any investments using them pose a "risk of significant financial detriment".[143]

In February 2023, ClientEarth filed a derivative action claim against Shell's board of directors for putting the company at risk by not transitioning away from fossil fuels quickly enough.[144] ClientEarth said the lawsuit marked 'the first time ever that a company's board has been challenged on its failure to properly prepare for the energy transition.'[144]Media coverage

editBritish tabloid newspaper reporting on climate change between 2000 and 2006 significantly diverged from the scientific consensus that climate change is driven by human activity.[145] The political leaning of newspapers influenced their likelihood of covering climate change, with the left-leaning The Guardian paper covering the issue more than the more conservative Times, Daily Telegraph and Daily Mail between 1997 and 2017.[146] The BBC has faced criticism for inviting fringe views into coverage of climate change,[147] and in 2018 admitted that it had covered climate change "wrong too often" and that it was false balance to invite deniers into its coverage.[148][149] Media coverage of the July 2022 heat wave corresponded to different political viewpoints, particularly whether climate change was mentioned or the severity of the heat wave was downplayed.[150]

Monarchy

editThe British royal family have advocated for climate change mitigation.[151] Charles III has expressed concern over the impacts of climate change and called for action on the issue among world leaders, including advocating for a "Marshall-like plan" to address it.[152][153] Elizabeth II called for action on climate change at COP26.[154][155] Prince William and Prince Harry also adopted climate change causes, with The Royal Foundation funding the Earthshot Prize under William's patronage.[151][156] Environmentalists have recognised their role in the cause, but have been critical of the ecological condition of the Crown Estate.[151]

Non-governmental organisations in the process

editWhile there are several instruments employed by central government to set targets and influence carbon behaviour in businesses and in individuals, how these actors achieve the reductions being set is not specified explicitly by DECC. In this case, businesses often rely on non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to help them deliver the targets being set by government regulation. These NGOs are experts in the carbon and energy field and are therefore consulted upon by businesses and the government in order to ensure that policies are delivered effectively. In that way DECC can be said to be at the centre of a “highly centralised network”[157] of carbon governance actors. This does detract from their hierarchical authority of DECC as they are the central figure in the network, it is simply a recognition that they need to “forge coalitions with societal interests in order to achieve their policy goals”.[158]

Climate Energy

editA good example of an NGO that has close links with the government and helps deliver their policy goals is Climate Energy. Established in 2005, they are an energy agency “specialising in advice and funding solutions”[159] for businesses and homeowners to help them with carbon efficiency. They offer a range of services including a consultancy service and grants for low carbon technologies. What is important to note here is that Climate Energy is a private company and therefore has no standing within government, but it does have a significant role to play in government legislation, as exemplified below.

Climate Energy and the Carbon Emission Reduction Target (CERT)

editCERT is another scheme introduced by the government that requires large energy supply companies to “make savings in the amount of CO2 emitted by householders”.<name="CE"/> It obliges energy companies to “promote and offer funding towards measures that improve energy efficiency in the home”.[160] While a good intentioned scheme, individual householders are arguably not in a position to best judge what measures are best suited to their position, or may not be aware of what grants are available to them. Climate Energy offers a consultancy service promising to “leverage funding from utilities to support projects”[160] for their clients through their connections in the industry. The initial government legislation was aimed at the energy suppliers with the overall aim of delivering individual household carbon reduction, but the actual delivery of this service has been performed by a private energy agency. The government is still the "central player"[161] in that they have implemented the policy, but Climate Energy's services ensure that it is delivered and represents further evidence of central government steering the actions of actors at lower levels.

Climate energy and The Green Deal

editThe Green Deal looks set to become a major part of carbon governance in the future, in that it is aimed at individual households in an attempt to improve carbon efficiency and make the transition for households to low-carbon energy as cost-effective as possible.[162] Climate Energy have actually been consulted by DECC as part of the consultation process before The Green Deal is implemented fully.[159] This is representative of a discretionary style of governance, in that the government department is keen to consult specialised agencies before implementing their scheme. The citing of Climate Energy as a consultee is used to legitimise the decision as it shows that a climate and energy efficiency expert has influenced the policy. The Green Deal will still be a centrally commissioned and regulated scheme, but the consultation process allows for specialist views to be taken into account when the policy is formulated.

By region

editLondon

editLondon is particularly vulnerable to climate change, with concern among hydrological experts that households in the city may run out of water before 2050.[163]

Scotland

editWales

editEngland

editThe government body responsible for climate change mitigation, the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC), is the “main external dynamic”[165] behind governing actions in this area, and is responsible for central co-ordination”.[166] The department may rely on other bodies to deliver its desired outcomes, but it is still ultimately responsible for the imposition of the rules and regulations that “steer (carbon) governmental action at the national level”.[167] It is therefore evident that carbon governance in England is hierarchical in nature, in that “legislative decisions and executive decisions”[167] are the main dynamic behind carbon governance action. This does not deny the existence of a network of bodies around DECC who are part of the process, but they are supplementary actors who are steered by central decisions. The other countries of the UK (Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) all have devolved assemblies who are responsible for the governance of carbon emissions in their respective countries.

See also

edit- 4 Degrees and Beyond International Climate Conference, a 2009 conference held in Oxford

- A Green New Deal

- Climate change in Europe

- Climate change in Ireland

- Committee on Climate Change

- Environmental effects of aviation in the United Kingdom

- Environmental inequality in the United Kingdom

- Environmental issues in the United Kingdom

- Green Party of England and Wales

- London Climate Change Agency

- Scottish Greens

References

edit- ^ "UK Climate Change Risk Assessment 2022". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Climate Change Act". Climate Change Laws of the World. Grantham Research Institute, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Columbia Law School. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Shepheard, Marcus (20 April 2020). "UK net zero target". Institute for government. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b Harvey, Fiona (4 December 2020). "UK vows to outdo other economies with 68% emissions cuts by 2030". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ a b "UK Parliament declares climate emergency". 1 May 2019. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Osaka, Shannon (13 September 2022). "The many paradoxes of Charles III as 'climate king'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ a b "2021 UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Final Figures" (PDF). BEIS. 7 February 2023.

- ^ "Analysis: Which countries are historically responsible for climate change?". Carbon Brief. 5 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (5 February 2019). "Climate change: UK CO2 emissions fall again". Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Final UK greenhouse gas emissions national statistics: 1990 to 2019". gov.uk. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo (11 May 2020). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- ^ "Carbon footprint for the UK and England to 2019". GOV.UK. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ "UK average footprint". www.carbonindependent.org. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (12 June 2019). "UK commits to 'net zero' emissions by 2050". BBC News. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "UK sets ambitious new climate target ahead of UN Summit". gov.ul. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "2019 Progress Report to Parliament". Climate Change Committee. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Ng, Gabriel (23 January 2021). "Introducing the UK Emissions Trading System". Cherwell. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "Where Britain's journey to insulation went wrong". the Guardian. 19 April 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "2022 Progress Report to Parliament". Climate Change Committee. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ "UK Scales Back £1 Billion Funding to Help Homes Cut Energy Use". Bloomberg.com. 29 July 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "UK must insulate homes or face a worse energy crisis in 2023, say experts". the Guardian. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Hausfather, Zeke; Peters, Glen (29 January 2020). "Emissions – the 'business as usual' story is misleading". Nature. 577 (7792): 618–20. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..618H. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00177-3. PMID 31996825.

- ^ Schuur, Edward A.G.; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Commane, Roisin; Ernakovich, Jessica; Euskirchen, Eugenie; Hugelius, Gustaf; Grosse, Guido; Jones, Miriam; Koven, Charlie; Leshyk, Victor; Lawrence, David; Loranty, Michael M.; Mauritz, Marguerite; Olefeldt, David; Natali, Susan; Rodenhizer, Heidi; Salmon, Verity; Schädel, Christina; Strauss, Jens; Treat, Claire; Turetsky, Merritt (2022). "Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47: 343–371. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011847.

Medium-range estimates of Arctic carbon emissions could result from moderate climate emission mitigation policies that keep global warming below 3°C (e.g., RCP4.5). This global warming level most closely matches country emissions reduction pledges made for the Paris Climate Agreement...

- ^ Phiddian, Ellen (5 April 2022). "Explainer: IPCC Scenarios". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

"The IPCC doesn't make projections about which of these scenarios is more likely, but other researchers and modellers can. The Australian Academy of Science, for instance, released a report last year stating that our current emissions trajectory had us headed for a 3°C warmer world, roughly in line with the middle scenario. Climate Action Tracker predicts 2.5 to 2.9°C of warming based on current policies and action, with pledges and government agreements taking this to 2.1°C.

- ^ Karoly, D. J. and P. A. Stott (2006). "Anthropogenic warming of central England temperature". Atmospheric Science Letters. 7 (4): 81–85. Bibcode:2006AtScL...7...81K. doi:10.1002/asl.136. S2CID 121456744.

- ^ a b c d e "Climate change in the UK". Met Office. Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "2014 on track to be England's hottest year in over three centuries". The Guardian. 3 December 2014. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Heatwave latest: Major incident declared as London hits 40C and fires burn". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "Chances of 40°C days in the UK increasing". Met Office. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Heavier rainfall from storms '100% for certain' linked to climate crisis, experts warn". The Independent. 18 February 2020. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "Flood map for planning - GOV.UK". flood-map-for-planning.service.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Vaughan, Adam (19 July 2022). "Temperature hits 40°C on the UK's hottest day on record". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Heatwave: The UK and Europe's record temperatures in maps and charts". BBC News. 19 July 2022. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Faulkner, Doug; Adams, Charley (15 July 2022). "Heatwave: National emergency declared after UK's first red extreme heat warning". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "Britain counts cost of historic heatwave as 13 die". Reuters. 20 July 2022. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Climate change: UK sea level rise speeding up - Met Office". BBC News. 28 July 2022. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Climate change: Rising sea levels threaten 200,000 England properties". BBC News. 15 June 2022. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Hanlon, Helen M.; Bernie, Dan; Carigi, Giulia; Lowe, Jason A. (30 June 2021). "Future changes to high impact weather in the UK". Climatic Change. 166 (3): 50. Bibcode:2021ClCh..166...50H. doi:10.1007/s10584-021-03100-5. ISSN 1573-1480. S2CID 235690689.

- ^ "Climate change will intensify UK droughts so we must take action now". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "UK and Global extreme events – Drought". Met Office. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Watts, Glenn; Battarbee, Richard W.; Bloomfield, John P.; Crossman, Jill; Daccache, Andre; Durance, Isabelle; Elliott, J. Alex; Garner, Grace; Hannaford, Jamie; Hannah, David M.; Hess, Tim; Jackson, Christopher R.; Kay, Alison L.; Kernan, Martin; Knox, Jerry (February 2015). "Climate change and water in the UK – past changes and future prospects". Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment. 39 (1): 6–28. doi:10.1177/0309133314542957. ISSN 0309-1333. S2CID 26176502.

- ^ a b "Climate change putting UK wildlife 'increasingly at risk'". The Guardian. 16 November 2015. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ a b "From badgers to bumblebees: how drought is affecting Britain's wildlife". The Guardian. 3 August 2022. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Graham, C. T.; Harrod, C. (April 2009). "Implications of climate change for the fishes of the British Isles". Journal of Fish Biology. 74 (6): 1143–1205. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02180.x. PMID 20735625. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Government gambles by excluding climate change from flood insurance deal Archived 19 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine FOE 6 December 2013

- ^ [1] Archived 14 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine WWF-UKMay 2017

- ^ Taylor, Chloe. "Britain's economy is already seeing a rapid shift due to climate change". CNBC. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Storm Dennis damage could cost insurance companies £225m Archived 20 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Guardian 20 February 2020

- ^ Storm Ciara expected to cost up to £200m in insurance claims Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Guardian 14 February 2020

- ^ Cameron's claims on flood defences don't stack up Archived 23 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine FOE 6 January 2014

- ^ Stern, N. (2006). "Summary of Conclusions". Executive summary (short) (PDF). Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change (pre-publication edition). HM Treasury. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ "HM Treasury" (PDF). GOV.UK. 22 November 2023. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008.

- ^ a b Carrington, Damian (22 May 2024). "'Never-ending' UK rain made 10 times more likely by climate crisis, study says". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Paavola, Jouni (5 December 2017). "Health impacts of climate change and health and social inequalities in the UK". Environmental Health. 16 (1): 113. doi:10.1186/s12940-017-0328-z. ISSN 1476-069X. PMC 5773866. PMID 29219089.

- ^ a b "Greener NHS » Health and climate change". www.england.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Rosane, Olivia (1 July 2020). "Chance of 40 Degree Celsius Days in UK 'Rapidly Increasing' Due to Climate Crisis". Ecowatch. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landler, Mark (1 November 2021). "Once a Leading Polluter, the U.K. Is Now Trying to Lead on Climate Change". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b R. Liu, Peiran; E. Raftery, Adrian (9 February 2021). "Country-based rate of emissions reductions should increase by 80% beyond nationally determined contributions to meet the 2 °C target". Communications Earth & Environment. 2 (1): 29. Bibcode:2021ComEE...2...29L. doi:10.1038/s43247-021-00097-8. PMC 8064561. PMID 33899003.

- ^ "Wind energy in the UK - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Gosden, Emily (18 November 2015). "UK coal plants must close by 2025, Amber Rudd announces". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ "End to coal power brought forward to October 2024". gov.uk. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ a b "UK Energy in Brief 2023" (PDF). United Kingdom Statistics Authority. 2023.

- ^ "Energy Trends March 2023" (PDF). DUKES (Digest of UK Energy Statistics). Department for Energy Security.

- ^ "Energy Trends renewables tables March 2023". DUKES (Digest of UK Energy Statistics). Department for Energy Security.

- ^ "How much of the UK's energy is renewable? | National Grid Group". National Grid. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Henry Foy (15 December 2013). "Spending to encourage use of electric cars falls flat". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Goodall, Olly (7 January 2022). "2021 sees largest-ever increase in plug-in sales". UK: Next Green Car. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

... the cumulative total of plug-in vehicles on UK roads – as of the end of December 2021 – to over 740,000. This total comprises around 395,000 BEVs and 350,000 PHEVs.

Overall in 2021, there were more than 190,000 sales of BEVs in the UK, with over 114,000 sales of PHEVs. Plug-in vehicles represented 18.6% of market share in 2021. - ^ International Energy Agency (IEA), Clean Energy Ministerial, and Electric Vehicles Initiative (EVI) (June 2020). "Global EV Outlook 2020: Enterign the decade of electric drive?". IEA Publications. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) See Statistical annex, pp. 247–252 (See Tables A.1 and A.12). - ^ Averchenkova, Alina; Fankhauser, Sam; Finnegan, Jared J. (7 February 2021). "The impact of strategic climate legislation: evidence from expert interviews on the UK Climate Change Act". Climate Policy. 21 (2): 251–263. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1819190. ISSN 1469-3062. S2CID 222114592.

- ^ "UK enshrines new target in law to slash emissions by 78% by 2035". GOV.UK. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Greener NHS » Delivering a net zero NHS". www.england.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Climate emergency bill offers real hope". The Guardian. 2 September 2020. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Lock, Helen (4 September 2020). "The New UK Climate Bill: Everything You Need to Know". Global Citizen. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (24 February 2021). "Carbon tax would be popular with UK voters, poll suggests". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Fuel duty - All you need to know". Politics.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Environmental taxes, reliefs and schemes for businesses". GOV.UK. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Hodgson, Camilla; Sheppard, David; Pickard, Jim (27 February 2021). "UK carbon trading system to launch in May". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Carter, Neil (31 January 2014). "The politics of climate change in the UK". WIREs Climate Change. 5 (3): 423–433. doi:10.1002/wcc.274. S2CID 155062628.

- ^ a b Sinha, Uttam Kumar (17 May 2010). "Climate Change and Foreign Policy: The UK Case". Strategic Analysis. 34 (3): 397–408. doi:10.1080/09700161003659095. ISSN 0970-0161. S2CID 154279944. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Gordon Brown puts $100bn price tag on climate adaptation". The Guardian. 26 June 2009. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Van Noorden, Richard (26 June 2009). "UK launches climate manifesto". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2009.604. ISSN 1476-4687. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Climate change: 'Fragile win' at COP26 summit under threat". BBC News. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "MI6 'green spying' on biggest polluters to ensure nations keep climate change promises". Sky News. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "COP26: UK pledges £290m to help poorer countries cope with climate change". BBC News. 8 November 2021. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ DECC website. Climate Change Levy. Accessed 16/12/2011

- ^ Jordan, A., Wurzel, R. K. W. & Zito, A. R. Comparative Conclusions-'New' Environmental Policy Instruments: An Evolution or a Revolution in Environmental Policy?. Environmental Politics. Volume 12 2003, p. 201–224 (p. 203)

- ^ Heritier, A. & Lehmkuhl, D. Introduction: The Shadow of Hierarchy and New Modes of Governance. Journal of Public Policy. Volume 28 2008, pp. 1–17 (p. 13).

- ^ Smith, S. & Swierzbinski, J. Assessing the performance of the UK ETS. Environmental Resource Economics. Volume 37 2007, pp. 131–158 (p. 134)

- ^ DECC website. Climate Change Agreements. Accessed 16/12/2011.[2].

- ^ Okereke, C. An Exploration of Motivations, Drivers and Barriers to Carbon Management: The UK FTSE 100. European Management Journal. Volume 25, pp. 475–486.

- ^ Sorensen, E. Metagovernance: The Changing Role of Politicians in Processes of Democratic Governance. American Review of Public Administration. Volume 36 2006, p. 98–114.

- ^ Bell, S. & Hindmoor, A. Rethinking governance: the centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge University Press 2009

- ^ DECC website. Enhanced Capital Allowances. Accessed 16/12/2011

- ^ "What is the ECA Scheme". Accessed 6/1/2013 Archived January 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rhodes, R. A. W. The Hollowing out of the State: The Changing Nature of the Public Service in Britain. The Political Quarterly. Volume 65 1994, p. 138–151 (p. 139).

- ^ Heritier, A. & Lehmkuhl, D. Introduction: The Shadow of Hierarchy and New Modes of Governance. Journal of Public Policy. Volume 28 2008, pp. 1–17 (p. 9)

- ^ Anderson, T. & Leal, D. Free Market Environmentalism. Westview Press 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Bell, S. & Hindmoor, A. Rethinking governance: the centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge University Press 2009, p124.

- ^ Jordan, A. et al. Policy Innovation or Muddling Through? New EPIs in the UK. In A. Jordan, R. K. W. Wurzel & A. R. Zito eds. New' Instruments of Environmental Governance?: National Experiences and Prospects. Frank Cass Publishers 2003, p179-199 (p184).

- ^ Smith, S. & Swierzbinski, J. Assessing the performance of the UK ETS. Environmental Resource Economics. Volume 37 2007, pp. 131–158 (p. 135).

- ^ Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Participating in the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS), published 17 December 2021, accessed 15 January 2021

- ^ European Commission website. Emissions Trading System. Accessed 16/12/2011.[3].

- ^ Rhodes, R. A. W. The Hollowing out of the State: The Changing Nature of the Public Service in Britain.The Political Quarterly. Volume 65 1994, pp. 138–151 (p. 138).

- ^ DECC website. EU Emissions Trading System. Accessed 16/12/2011. "EU Emissions Trading System - Department of Energy and Climate Change". Archived from the original on 20 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011..

- ^ Environment Agency website. About us. Accessed 16 December 2011. [4].

- ^ Bell, S. & Hindmoor, A. Rethinking governance: the centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge University Press 2009, p. 88.

- ^ DECC website. CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme. Accessed 16 December 2011. [5].

- ^ Smith, S. & Swierzbinski, J. Assessing the performance of the UK ETS. Environmental Resource Economics. Volume 37 2007, pp. 131–158 (p. 133).

- ^ Environmental Agency website. CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme. Accessed 16/12/2011. [6].

- ^ DECC website. CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme. Accessed 16/12/2011

- ^ Heritier, A. & Lehmkuhl, D. Introduction: The Shadow of Hierarchy and New Modes of Governance. Journal of Public Policy. Volume 28 2008, pp. 1–17 (p. 8).

- ^ a b "Climate change adaptation: policy information". GOV.UK.

- ^ "Understanding climate adaptation and the third National Adaptation Programme (NAP3)". GOV.UK.

- ^ Porter, James J.; Dessai, Suraje; Tompkins, Emma L. (1 November 2014). "What do we know about UK household adaptation to climate change? A systematic review". Climatic Change. 127 (2): 371–379. Bibcode:2014ClCh..127..371P. doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1252-7. ISSN 1573-1480. PMC 4372777. PMID 25834299. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Keskitalo, E. Carina H.; Vulturius, Gregor; Scholten, Peter (1 March 2014). "Adaptation to climate change in the insurance sector: examples from the UK, Germany and the Netherlands". Natural Hazards. 71 (1): 315–334. doi:10.1007/s11069-013-0912-7. ISSN 1573-0840. S2CID 113397575.

- ^ "How is the Bank of England responding to climate change?". www.bankofengland.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Drone photos show 'incredible' impact of beavers during drought". The Independent. 22 August 2022. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "New legal protections for wild beavers in England a 'gamechanger'". The Independent. 21 July 2022. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Who we are". Teach the Future. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "Digital Hub". Teach the Future. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "72% of Britons think climate change is a result of human activity, up 20pts since 2013 | YouGov". yougov.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Three-quarters of adults in Great Britain worry about climate change - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ harrisson, thomas (11 September 2019). "Analysis: The UK politicians who talk the most about climate change". Carbon Brief. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Boris Johnson's climate push loses its champion as Tories eye new leader". POLITICO. 11 July 2022. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Nigel Lawson's climate-change denial charity 'intimidated' environmental expert - Climate Change - Environment - The Independent". Independent.co.uk. 11 May 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "Who We Are". GWPF.

- ^ Cooke, Phoebe (14 September 2020). "New UKIP Leader Neil Hamilton Thinks Climate Change is a 'Hoax'". DeSmog. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "Ukip's energy and climate policies under the spotlight | Bob Ward". The Guardian. 4 March 2013. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "UK's climate science deniers rebrand". POLITICO. 11 October 2021. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Why UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak isn't talking about net zero". POLITICO. 7 October 2021. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Hogan, Fintan (1 July 2024). "At least 30 Reform candidates have cast doubt on human-induced global heating". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Motorway blockades and green new deal crusaders: the UK's new climate activists". the Guardian. 17 September 2021. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Climate Camp disbanded". the Guardian. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "The evolution of Extinction Rebellion". the Guardian. 4 August 2020. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Jones, Sam (12 February 2014). "Church of England vows to fight 'great demon' of climate change". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Live Earth gigs send eco-warning". 8 July 2007. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Smirke, Richard (12 July 2019). "'We Must Act Quickly': British Music Biz Declares Climate Emergency". Billboard. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "New Youth Climate Lawsuit Launched Against UK Government on Five Year Anniversary of Paris Agreement". DeSmog. 12 December 2020. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Young People v UK Government: Safeguard our Lives and our Families!". Plan B. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Keating, Cecilia (11 December 2020). "'A quantum leap for climate action': UK pledges to end support for overseas oil and gas projects". BusinessGreen. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ [2022] EWHC 1233 (Ch) and B Mercer, 'Lecturers' USS lawsuit frustrated by centuries-old precedent' (24 May 2022) Pensions Expert Archived 2023-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ T Williams, 'Commit to restoring '£7,000' pension losses now, say USS members' Times Higher Ed Archived 2023-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ E McGaughey, 'Holding USS Directors Accountable, and the Start of the End for Foss v Harbottle?' (18 July 2022) Oxford Business Law Blog Archived 2023-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "We're taking Shell's Board of Directors to court". ClientEarth. 9 February 2023. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ Boykoff, Maxwell T; Mansfield, Maria (28 April 2008). "'Ye Olde Hot Aire'*: reporting on human contributions to climate change in the UK tabloid press". Environmental Research Letters. 3 (2): 024002. Bibcode:2008ERL.....3d4002B. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/3/2/024002. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 3252832.

- ^ Saunders, Clare; Grasso, Maria T.; Hedges, Craig (1 August 2018). "Attention to climate change in British newspapers in three attention cycles (1997–2017)". Geoforum. 94: 94–102. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.05.024. hdl:10871/33043. ISSN 0016-7185. S2CID 149605661.

- ^ "Review of BBC Science Coverage Finds Room for Improvement". www.science.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "BBC admits 'we get climate change coverage wrong too often'". The Guardian. 7 September 2018. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Pearce, Rosamund (7 September 2018). "Exclusive: BBC issues internal guidance on how to report climate change". Carbon Brief. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "'Blowtorch Britain' captures global attention". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Bawden, Tom (15 October 2021). "The Royal Family has done much for the climate change cause but needs to do more". inews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Military-style Marshall Plan needed to combat climate change, says Prince Charles". Reuters. 21 September 2020. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Cop26 'literally the last chance saloon' to save planet – Prince Charles". the Guardian. 31 October 2021. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "COP26: Act now for our children, Queen urges climate summit". BBC News. 1 November 2021. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Queen 'irritated' by climate change inaction in COP26 build-up". BBC News. 15 October 2021. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "What have all the royals said about climate change?". The Independent. 15 October 2021. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Evans, J. Environmental Governance. Routledge 2012, p. 109.

- ^ Bell, S. & Hindmoor, A. Rethinking governance: the centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge University Press 2009, p. 89.

- ^ a b Climate Energy website.About us. Accessed 16 December 2011. [7] Archived 2011-12-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Climate Energy website. Local Authorities & RSL - CERT Funding. Accessed 16 December 2011. "Carbon Emissions Reduction Target (CERT): Paving the way for the Green Deal". Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011..

- ^ Bell, S. & Hindmoor, A. Rethinking governance: the centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge University Press 2009, p. 79.

- ^ DECC website. The Green Deal. Accessed 16 December 2011. [8].

- ^ Saphora Smith (16 May 2022). "London could run out of water in 25 years as cities worldwide face rising risk of drought, report warns". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

London already receives about half the amount of rain that falls in New York City, and climate change will increase the frequency and intensity of droughts in the region

- ^ "Climate change: New planning policy in Wales a UK first". BBC News. 28 September 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Davies, J. S. The Governance of Urban Regeneration: A critique of the 'Governing without Government' Thesis. Public Administration. Volume 80 2002, p. 301–322 (p. 309)

- ^ Bell, S. & Hindmoor, A. Rethinking governance: the centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge University Press 2009, p. 87.

- ^ a b Heritier, A. & Lehmkuhl, D. Introduction: The Shadow of Hierarchy and New Modes of Governance. Journal of Public Policy. Volume 28 2008, p. 1–17 (p. 2).

External links

edit- Climate change in the UK at the Met Office website

- UK Climate Change Committee

- United Kingdom Summary | World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal

- What will climate change look like near me? at BBC News

- Climate change insights at the Office for National Statistics

- Adapting to climate change at the UK government website

- MSPACE Early-warning system: Climate-smart spatial management of UK fisheries, aquaculture and conservation (April 2024)