Knossos (pronounced /(kə)ˈnɒsoʊs, -səs/; Ancient Greek: Κνωσσός, romanized: Knōssós, pronounced [knɔː.sós]; Linear B: 𐀒𐀜𐀰 Ko-no-so[2]) is a Bronze Age archaeological site in Crete. The site was a major centre of the Minoan civilization and is known for its association with the Greek myth of Theseus and the minotaur. It is located on the outskirts of Heraklion, and remains a popular tourist destination. Knossos is considered by many to be the oldest city in Europe.[3]

Κνωσσός | |

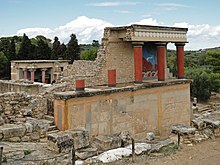

Reconstructed North Entrance | |

Map of Crete | |

| Location | Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

|---|---|

| Region | North central coast, 5 km (3.1 mi) southeast of Heraklion |

| Coordinates | 35°17′53″N 25°9′47″E / 35.29806°N 25.16306°E |

| Type | Minoan palace |

| Area | Total inhabited area: 10 km2 (3.9 sq mi). Palace: 14,000 m2 (150,000 sq ft)[1] |

| History | |

| Founded | Settlement around 7000 BC; first palace around 1900 BC |

| Abandoned | Palace abandoned Late Minoan IIIC, 1380–1100 BC |

| Periods | Neolithic to Late Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Minoan, Mycenaean |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1900–present |

| Archaeologists | Minos Kalokairinos, Arthur Evans, David George Hogarth, Duncan Mackenzie, Theodore Fyfe, Christian Doll, Piet de Jong, John Davies Evans |

| Condition | Restored and maintained for visitation. |

| Management | 23rd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism |

Knossos is dominated by the monumental Palace of Minos. Like other Minoan palaces, this complex of buildings served as a combination religious and administrative centre rather than a royal residence. The earliest parts of the palace were built around 1900 BC in an area that had been used for ritual feasting since the Neolithic. The palace was continually renovated and expanded over the next five centuries until its final destruction around 1350 BC.

The site was first excavated by Minos Kalokairinos in 1877. In 1900, Arthur Evans undertook more extensive excavations which unearthed most of the palace as well as many now-famous artifacts including the Bull-Leaping Fresco, the snake goddess figurines, and numerous Linear B tablets. While Evans is often credited for discovering the Minoan Civilization, his work is controversial in particular for his inaccurate and irreversible reconstructions of architectural remains at the site.

History

editNeolithic period

editKnossos was settled around 7000 BC during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, making it the oldest known settlement in Crete. Radiocarbon dating has suggested dates around 7,030-6,780 BCE.[4] The initial settlement was a hamlet of 25–50 people who lived in wattle and daub huts, kept animals, grew crops, and, in the event of tragedy, buried their children under the floor. Remains from this period are concentrated in the area which would later become the central court of the palace, suggesting continuity in ritual activity.[5][6][7]

In the Early Neolithic (6000–5000 BC), a village of 200–600 persons occupied most of the area of the later palace and the slopes to the north and west. Residents lived in one- or two-room square houses of mud-brick walls set on socles of stone, either field stone or recycled stone artifacts. The inner walls were lined with mud-plaster. The roofs were flat, composed of mud over branches. The residents dug hearths at various locations in the centre of the main room. This village had an unusual feature: one house under the West Court contained eight rooms and covered 50 m2 (540 sq ft). The walls were at right angles and the door was centred. Large stones were used for support under points of greater stress. The fact that distinct sleeping cubicles for individuals was not the custom suggests storage units of some sort.[citation needed]

The settlement of the Middle Neolithic (5000–4000 BC), housed 500–1000 people in more substantial and presumably more family-private homes. Construction was the same, except the windows and doors were timbered, a fixed, raised hearth occupied the centre of the main room, and pilasters and other raised features (cabinets, beds) occupied the perimeter. Under the palace was the Great House, a 100 m2 (1,100 sq ft) area stone house divided into five rooms with meter-thick walls suggesting a second storey was present. The presence of the house, which is unlikely to have been a private residence like the others, suggests a communal or public use; i.e., it may have been the predecessor of a palace. In the Late or Final Neolithic (two different but overlapping classification systems, around 4000–3000 BC), the population increased dramatically.[citation needed]

Bronze Age

edit| Timespan | Period | |

|---|---|---|

| 3100–2650 BC | EM I | Prepalatial |

| 2650–2200 BC | EM II | |

| 2200–2100 BC | EM III | |

| 2100–1925 BC | MM IA | |

| 1925–1875 BC | MM IB | Protopalatial |

| 1875–1750 BC | MM II | |

| 1750–1700 BC | MM III | Neopalatial |

| 1700–1625 BC | LM IA | |

| 1625–1470 BC | LM IB | |

| 1470–1420 BC | LM II | Postpalatial |

| 1420–1330 BC | LM IIIA | |

| 1330–1200 BC | LM IIIB | |

| 1200–1075 BC | LM IIIC | |

It is believed that the first Cretan palaces were built soon after c. 2000 BC, in the early part of the Middle Minoan period, at Knossos and other sites including Malia, Phaestos and Zakro. These palaces, which were to set the pattern of organisation in Crete and Greece through the second millennium, were a sharp break from the Neolithic village system that had prevailed thus far. The building of the palaces implies greater wealth and a concentration of authority, both political and religious. It is suggested that they followed eastern models such as those at Ugarit on the Syrian coast and Mari on the upper Euphrates.[8]

The early palaces were destroyed during Middle Minoan II, sometime before c. 1700, almost certainly by earthquakes to which Crete is prone. By c. 1650, they had been rebuilt on a grander scale and the period of the second palaces (c. 1650 – c. 1450) marks the height of Minoan prosperity. All the palaces had large central courtyards which may have been used for public ceremonies and spectacles. Living quarters, storage rooms and administrative centres were positioned around the court and there were also working quarters for skilled craftsmen.[8]

The palace of Knossos was by far the largest, covering three acres with its main building alone and five acres when separate out-buildings are considered. It had a monumental staircase leading to state rooms on an upper floor. A ritual cult centre was on the ground floor. The palace stores occupied sixteen rooms, the main feature in these being the pithoi that were large storage jars up to five feet tall. They were mainly used for storage of oil, wool, wine, and grain. Smaller and more valuable objects were stored in lead-lined cists. The palace had bathrooms, toilets, and a drainage system.[8] A theatre was found at Knossos that would have held 400 spectators (an earlier one has been found at Phaestos). The orchestral area was rectangular, unlike later Athenian models, and they were probably used for religious dances.[9]

Building techniques at Knossos were typical. The foundations and lower course were stonework with the whole built on a timber framework of beams and pillars. The main structure was built of large, unbaked bricks. The roof was flat with a thick layer of clay over brushwood. Internal rooms were brightened by light-wells and columns of wood, many fluted, were used to lend both support and dignity. The chambers and corridors were decorated with frescoes showing scenes from everyday life and scenes of processions. Warfare is conspicuously absent. The fashions of the time may be seen in depictions of women in various poses. They had elaborately dressed hair and wore long dresses with flounced skirts and puffed sleeves. Their bodices were tightly drawn in round their waists and their breasts were exposed.[9]

The prosperity of Knossos was primarily based upon the development of native Cretan resources such as oil, wine, and wool. Another factor was the expansion of trade, evidenced by Minoan pottery found in Egypt, Syria, Anatolia, Rhodes, the Cyclades, Sicily, and mainland Greece. There seem to have been strong Minoan connections with Rhodes, Miletus, and Samos. Cretan influence may be seen in the earliest scripts found in Cyprus. The main market for Cretan wares was the Cyclades where there was a demand for pottery, especially the stone vases. It is not known whether the islands were subject to Crete or just trading partners, but there certainly was strong Cretan influence.[10]

Around 1450 BC, the palaces at Malia, Phaestos, and Zakros were destroyed, leaving Knossos as the sole surviving palace on Crete. In this final period, Knossos seems to have been influenced or perhaps ruled by people from the mainland. Greek became the administrative language and the material culture shows parallels with Mycenaean styles, for instance in the architecture of tombs and styles of pottery.[11]

Around 1350 BC, the palace was destroyed and not rebuilt. The building was ravaged by a fire which triggered the collapse of the upper stories. It is not known whether this final destruction was intentional or the result of a natural disaster such as an earthquake. While parts of the palace may have been used for later ceremonies and the town of Knossos saw a resurgence around 1200 BC, the building and its associated institutions were never restored.[5]

Classical and Roman period

editAfter the Bronze Age, the town of Knossos continued to be occupied. By 1000 BC, it had reemerged as one of the most important centres of Crete. The city had two ports, one at Amnisos and another at Heraklion.

According to the ancient geographer Strabo the Knossians colonized the city of Brundisium in Italy.[13] In 343 BC, Knossos was allied with Philip II of Macedon. The city employed a Phocian mercenary named Phalaikos against their enemy, the city of Lyttus. The Lyttians appealed to the Spartans who sent their king Archidamus III against the Knossians.[14] In Hellenistic times Knossos came under Egyptian influence, but despite considerable military efforts during the Chremonidean War (267–261 BC), the Ptolemies were not able to unify the warring city states. In the third century BC Knossos expanded its power to dominate almost the entire island, but during the Lyttian War in 220 BC it was checked by a coalition led by the Polyrrhenians and the Macedonian king Philip V.[15]

Twenty years later, during the Cretan War (205–200 BC), the Knossians were once more among Philip's opponents and, through Roman and Rhodian aid, this time they managed to liberate Crete from the Macedonian influence.[16] With Roman aid, Knossos became once more the first city of Crete, but, in 67 BC, the Roman Senate chose Gortys as the capital of the newly created province Creta et Cyrene.[17] In 36 BC, Knossos became a Roman colony named Colonia Iulia Nobilis.[18] The colony, which was built using Roman-style architecture,[18] was situated within the vicinity of the palace, but only a small part of it has been excavated.

The identification of Knossos with the Bronze Age site is supported by the Roman coins that were scattered over the fields surrounding the pre-excavation site, then a large mound named Kephala Hill, elevation 85 m (279 ft) from current sea level. Many of them were inscribed with Knosion or Knos on the obverse and an image of a Minotaur or Labyrinth on the reverse.[19] The coins came from the Roman settlement of Colonia Julia Nobilis Cnossus, a Roman colony placed just to the north of, and politically including, Kephala. The Romans believed they were the first to colonize Knossos.[20]

Post-Roman history

editIn 325, Knossos became a diocese, suffragan of the metropolitan see of Gortyna.[21] In Ottoman Crete, the see of Knossos was in Agios Myron, 14 km to the southwest.[21] The bishops of Gortyn continued to call themselves bishops of Knossos until the nineteenth century.[22] The diocese was abolished in 1831.[21]

During the ninth century AD the local population shifted to the new town of Chandax (modern Heraklion). By the thirteenth century, it was called the Makruteikhos 'Long Wall'.

In its modern history, the name Knossos is used only for the archaeological site. It was extensively excavated by Arthur Evans in the early 20th century, and Evans' residence at the site served as a military headquarters during World War II. Knossos is now situated in the expanding suburbs of Heraklion.

Legends

editIn Greek mythology, King Minos dwelt in a palace at Knossos. He had Daedalus construct a labyrinth, a very large maze in which to retain his son, the Minotaur. Daedalus also built a dancing floor for Queen Ariadne.[23] The name "Knossos" was subsequently adopted by Arthur Evans.

As far as is currently known, it was William Stillman, the American consul who published Kalokairinos' discoveries, who, seeing the sign of the double axe (labrys) on the massive walls partly uncovered by Kalokairinos, first associated the complex with the labyrinth of legend, calling the ruins "labyrinthine."[24] Evans agreed with Stillman. The myth of the Minotaur tells that Theseus, a prince from Athens, whose father was an ancient Greek king named Aegeus, the basis for the name of the Greek sea (the Aegean Sea), sailed to Crete, where he was forced to fight a terrible creature called the Minotaur. The Minotaur was a half man, half bull, and was kept in the Labyrinth – a building like a maze – by King Minos, the ruler of Crete. The king's daughter, Ariadne, fell in love with Theseus. Before he entered the Labyrinth to fight the Minotaur, Ariadne gave him a ball of thread which he unwound as he went into the Labyrinth so that he could find his way back by following it. Theseus killed the Minotaur, and then he and Ariadne fled from Crete, escaping her angry father.

As it turns out, there probably was an association of the word labyrinth, whatever its etymology, with ancient Crete. The sign of the double axe was used throughout the Mycenaean world as an apotropaic mark: its presence on an object would prevent it from being "killed". Axes were scratched on many of the stones of the palace. It appears in pottery decoration and is a motif of the Shrine of the Double Axes at the palace, as well as of many shrines throughout Crete and the Aegean. And finally, it appears in Linear B on Knossos Tablet Gg702 as da-pu2-ri-to-jo po-ti-ni-ja, which probably represents the Mycenaean Greek, Daburinthoio potniai, "to the mistress of the Labyrinth," recording the distribution of one jar of honey.[25] A credible theory uniting all the evidence has yet to be formulated.

Knossos appears in other later legends and literature. Herodotus wrote that Minos, the legendary king of Knossos, established a thalassocracy (sea empire). Thucydides accepted the tradition and added that Minos cleared the sea of pirates, increased the flow of trade and colonised many Aegean islands.[10] Other literature describes Rhadamanthus as the mythological lawgiver of Crete. Cleinias of Crete attributes to him the tradition of Cretan gymnasia and common meals in Book I of Plato's Laws, and describes the logic of the custom as enabling a constant state of war readiness.

Excavation history

editThe site of Knossos was identified by Minos Kalokairinos, who excavated parts of the West Wing in the winter of 1878-1879. The British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans (1851–1941) and his team began long-term evacuations from 1900 to 1913, and from 1922 to 1930.[26][27]

Its size far exceeded his original expectations, as did the discovery of two ancient scripts, which he termed Linear A and Linear B, to distinguish their writing from the pictographs also present. From the layering of the palace, Evans developed an archaeological concept of the civilization that used it, which he called Minoan, following the pre-existing custom of labelling all objects from the location Minoan.

Since their discovery, the ruins have been the centre of excavation, tourism, and occupation as a headquarters by governments warring over the control of the eastern Mediterranean in two world wars.

John Davies Evans (no relation to Arthur Evans) undertook further excavations in pits and trenches over the palace, focusing on the Neolithic.[7]

Palace complex

editThe palace at Knossos was continuously renovated and modified throughout its existence. The currently visible palace is an accumulation of features from various periods, alongside modern reconstructions which are often inaccurate. Thus, the palace was never exactly as it appears today.[28][29]

Layout

editLike other Minoan palaces, Knossos was arranged around a rectangular central court. This court was twice as long north-south as it was east-west, an orientation that would have maximized sunlight, and positioned important rooms towards the rising sun.[30][31][32][33]

The central court is believed to have been used for rituals and festivals. One of these festivals is believed to be depicted in the Grandstand Fresco. Some scholars have suggested that bull-leaping would have taken place in the courts, though others have argued that the paving would not have been optimal for the animals or the people, and that the restricted access points would have kept the spectacle too far out of public view.[30][31]

The 6 acres (24,000 m2) of the palace included a theater, a main entrance on each of its four cardinal faces, and extensive storerooms.

Location

editThe palace was built on Kephala Hill, 5 km (3.1 mi) south of the coast. The site is located at the confluence of two streams called the Vlychia and the Kairatos, which would have provided drinking water to the ancient inhabitants. Looming over the right bank of the Vlychia, on the opposite shore from Knossos, is Gypsades Hill, on whose eastern side the Minoans quarried their gypsum.

Though it was surrounded by the town of Knossos, this hill was never an acropolis in the Greek sense. It had no steep heights, remained unfortified, and was not very high off the surrounding ground.[34]

The Royal Road is the last vestige of a Minoan road that connected the port to the palace complex. Today a modern road, Leoforos Knosou, built over or replacing the ancient roadway, serves that function and continues south.

Storage

editThe palace had extensive storage magazines which were used for agricultural commodities as well as tableware. Enormous sets of high quality tableware were stored in the palaces, often produced elsewhere in Crete.[35] Pottery at Knossos is prolific, heavily-decorated and uniquely-styled by period. In Minoan chronology, the standard relative chronology is largely based on pottery styles and is thus used to assign dates to layers of the palace.

Water management

editThe palace had at least three separate water-management systems: one for supply, one for drainage of runoff, and one for drainage of waste water.

Aqueducts brought fresh water to Kephala hill from springs at Archanes, about 10 km away. Springs there are the source of the Kairatos river, in the valley in which Kephala is located. The aqueduct branched to the palace and to the town. Water was distributed at the palace by gravity feed through terracotta pipes to fountains and spigots. The pipes were tapered at one end to make a pressure fit, with rope for sealing. Unlike Mycenae, no hidden springs have been discovered.

Sanitation drainage was through a closed system leading to a sewer apart from the hill. The queen's megaron contained an example of the first known water-flushing system latrine adjoining the bathroom. This toilet was a seat over a drain that was flushed by pouring water from a jug. The bathtub located in the adjoining bathroom similarly had to be filled by someone heating, carrying, and pouring water, and must have been drained by overturning into a floor drain or by bailing. This toilet and bathtub were exceptional structures within the 1,300-room complex.

As the hill was periodically drenched by torrential rains, a runoff system was a necessity. It began with channels in the flat surfaces, which were zigzag and contained catchment basins to control the water velocity. Probably the upper system was open. Manholes provided access to parts that were covered.

Some links to photographs of parts of the water-collection-management system follow.

- Runoff system.[36] Sloped channels lead from a catchment basin.

- Runoff system.[37] Note the zig-zags and the catchment basin.

Ventilation

editDue to its placement on the hill, the palace received sea breezes during the summer. It had porticoes and air shafts.

Minoan columns

editThe palace also includes the Minoan column, a structure notably different from Greek columns. Unlike the stone columns that are characteristic of Greek architecture, the Minoan column was constructed from the trunk of a cypress tree, which is common to the Mediterranean. While Greek columns are smaller at the top and wider at the bottom to create the illusion of greater height (entasis), the Minoan columns are smaller at the bottom and wider at the top, a result of inverting the cypress trunk to prevent sprouting once in place.[38] The columns at the Palace of Minos were plastered, painted red and mounted on stone bases with round, pillow-like capitals.

Frescoes

editThe palace at Knossos used considerable amounts of colour, as were Greek buildings in the classical period. In the EM Period, the walls and pavements were coated with a pale red derived from red ochre. In addition to the background colouring, the walls displayed fresco panel murals, entirely of red. In the subsequent MM Period, with the development of the art, white and black were added, and then blue, green, and yellow. The pigments were derived from natural materials, such as ground hematite. Outdoor panels were painted on fresh stucco with the motif in relief; indoor, on fresh, pure plaster, softer than the plaster with additives ordinarily used on walls.[39]

The decorative motifs were generally bordered scenes: humans, legendary creatures, animals, rocks, vegetation, and marine life. The earliest imitated pottery motifs. Most have been reconstructed from various numbers of flakes fallen to the floor. Evans had various technicians and artists work on the project, some artists, some chemists, and restorers. The symmetry and use of templates made possible a degree of reconstruction beyond what was warranted by only the flakes. For example, if evidence of the use of a certain template existed scantily in one place, the motif could be supplied from the template found somewhere else. Like the contemporary murals in the funerary art of the Egyptians, certain conventions were used that also assisted prediction. For example, male figures are shown with darker or redder skin than female figures.

Some archaeological authors have objected that Evans and his restorers were not discovering the palace and civilization as it was, but were creating a modern artifact based on contemporary art and architecture.[40]

Throne Room

editThe centrepiece of the "Minoan" palace was the so-called Throne Room or Little Throne Room,[41] dated to LM II. This chamber has an alabaster seat which Evans referred to as a "throne" built into the north wall. On three sides of the room are gypsum benches. On the south side of the throne room there is a feature called a lustral basin, so-called because Evans found remains of unguent flasks inside it and speculated that it had been used as part of an annointing ritual.[citation needed]

The room was accessed from an anteroom through double doors. The anteroom was connected to the central court, which was four steps up through four doors. The anteroom had gypsum benches also, with carbonized remains between two of them thought possibly to be a wooden throne. Both rooms are located in the ceremonial complex on the west of the central court.

The throne is flanked by the Griffin Fresco, with two griffins couchant (lying down) facing the throne, one on either side. Griffins were important mythological creatures, also appearing on seal rings, which were used to stamp the identities of the bearers into pliable material, such as clay or wax.

The actual use of the room and the throne is unclear.

The two main theories are as follows:

- The seat of a priest-king or a queen. This is the older theory, originating with Evans. In that regard Matz speaks of the "heraldic arrangement" of the griffins, meaning that they are more formal and monumental than previous Minoan decorative styles. In this theory, the Mycenaeans would have held court in this room, as they came to power in Knossos at about 1,450. The "lustral basin" and the location of the room in a sanctuary complex cannot be ignored; hence, "priest-king".

- A room reserved for the epiphany of a goddess,[42] who would have sat in the throne, either in effigy, or in the person of a priestess, or in imagination only. In that case the griffins would have been purely a symbol of divinity rather than a heraldic motif.

-

The throne from which the room was named, not the only throne at Knossos

-

The throne room prior to reconstruction

Notable residents

edit- Aenesidemus (first century BC), sceptical philosopher

- Chersiphron (sixth century BC), architect

- Epimenides (sixth century BC), seer and philosopher-poet

- Ergoteles of Himera (fifth century BC), expatriate Olympic runner

- Metagenes (6th century BC), architect

- Minos (mythical), father of the Minotaur

See also

editCitations

edit- ^ McEnroe, John C. (2010). Architecture of Minoan Crete: Constructing Identity in the Aegean Bronze Age. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 50. However, Davaras 1957, p. 5, an official guide book in use in past years, gives the dimensions of the palace as 150 m (490 ft) square, about 20,000 m2 (220,000 sq ft).

- ^ Hooker, J. T. (1991). Linear B: An Introduction. Bristol Classical Press. pp. 71, 50. ISBN 978-0-906515-62-4.

- ^ Whitelaw, Todd (2000). "Beyond the palace: A century of investigation at Europe's oldest city". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies: 223, 226.

- ^ Facorellis, Yorgos & Maniatis, Y.. (2013). Radiocarbon Dates from the Neolithic Settlement of Knossos:: An Overview. 10.2307/j.ctt5vj96p.17.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2012, p. 464

- ^ Düring, Bleda S (2011). The prehistory of Asia Minor: from complex hunter-gatherers to early urban societies. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 126.

- ^ a b McEnroe, John C (2010). Architecture of Minoan Crete: constructing identity in the Aegean Bronze Age. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 12–17.

- ^ a b c Bury & Meiggs 1975, p. 9

- ^ a b Bury & Meiggs 1975, p. 10

- ^ a b Bury & Meiggs 1975, pp. 11–12

- ^ Bury & Meiggs 1975, pp. 17–18

- ^ Wroth, Warwick (1886). Catalogue of the Greek Coins of Crete and the Aegean Islands. Order of the Trustees. pp. xxxiv.

- ^ Strabo, 6,3,6.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, XVI 61,3–4.

- ^ Polybius, Histories, IV 53–55.

- ^ Theocharis Detorakis, A History of Crete, Heraklion, 1994.

- ^ "Crete". UNRV.com. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- ^ a b Sweetman, Rebecca J. (10 June 2011). "Roman Knossos: Discovering the City through the Evidence of Rescue Excavations". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 105: 339–379. doi:10.1017/S0068245400000459. S2CID 191885145.

- ^ Gere 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Chaniotis, Angelos (1999). From Minoan farmers to Roman traders: sidelights on the economy of ancient Crete. Stuttgart: Steiner. pp. 280–282.

- ^ a b c Demetrius Kiminas, The Ecumenical Patriarchate, 2009, ISBN 1434458768, p. 122

- ^ Oliver Rackham and Jennifer Moody (1996). The Making of the Cretan Landscape. Manchester University Press. pp. 94, 104. ISBN 0-7190-3646-1.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 18.590-2.

- ^ Evans 1894, p. 281.

- ^ Ventris, Michael; Chadwick, John (1973). Documents in Mycenaean Greek (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 310, 538, 574.

- ^ McEnroe, John C. (2010). Architecture of Minoan Crete: Constructing Identity in the Aegean Bronze Age. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 50.

- ^ Watrous, L. Vance (2021). Minoan Crete: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–26. ISBN 9781108440493.

- ^ Preziosi, Donald; Hitchcock, Louise (1999). Aegean. Oxford University Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9780192842084.

- ^ McEnroe, John C (2010). Architecture of Minoan Crete: constructing identity in the Aegean Bronze Age. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 79.

- ^ a b Hitchcock, Louise (2012). "Minoan Architecture". In Cline, Eric (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford University Press. pp. 189–199. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199873609.013.0014. ISBN 978-0199873609.

- ^ a b Lupack, Susan (2012). "Crete". In Cline, Eric (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford University Press. pp. 251–262. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199873609.013.0019. ISBN 978-0199873609.

- ^ McEnroe, John C. (2010). Architecture of Minoan Crete: Constructing Identity in the Aegean Bronze Age. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 84–85.

- ^ Macdonald, Colin F. (2003). "The Palaces of Minos at Knossos". Athena Review. 3 (3). Athena Publications, Inc. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Hall, HR (November 20, 1902). "The Mycenaean Discoveries in Crete". Nature. 67 (1725): 58. Bibcode:1902Natur..67...57H. doi:10.1038/067057a0. S2CID 4005358.

- ^ Schoep, Ilse (2012). "Crete". In Cline, Eric (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford University Press. pp. 113–125. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199873609.013.0008. ISBN 978-0199873609.

- ^ JPEG image. minoancrete.com, Ian Swindale. Retrieved on 2013-05-12.

- ^ JPEG image. Dartmouth.edu. Retrieved on 2012-01-02.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Knossos fieldnotes, Modern Antiquarian (2007)

- ^ Evans 1921, pp. 532–536.

- ^ Gere 2009, Chapter Four: The Concrete Labyrinth: 1914–1935.

- ^ Matz, The Art of Crete and Early Greece Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2010, ISBN 1-163-81544-6, uses this term.

- ^ Peter Warren: Minoan Religion as Ritual Action, Volume 72 of Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, 1988, the University of Michigan

General and cited sources

edit- Begg, D.J. Ian (2004), "An Archaeology of Palatial Mason's Marks on Crete", in Chapin, Ann P. (ed.), ΧΑΡΙΣ: Essays in Honor of Sara A. Immerwahr, Hesperia Supplement 33, pp. 1–28

- Benton, Janetta Rebold and Robert DiYanni.Arts and Culture: An introduction to the Humanities, Volume 1 (Prentice Hall. New Jersey, 1998), 64–70.

- Bourbon, F. Lost Civilizations (New York, Barnes and Noble, 1998), 30–35.

- Bury, J. B.; Meiggs, Russell (1975). A History of Greece (Fourth ed.). London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 0-333-15492-4.

- Davaras, Costos (1957). Knossos and the Herakleion Museum: Brief Illustrated Archaeological Guide. Translated by Doumas, Alexandra. Athens: Hannibal Publishing House.

- Driessen, Jan (1990). An early destruction in the Mycenaean palace at Knossos: a new interpretation of the excavation field-notes of the south-east area of the west wing. Acta archaeologica Lovaniensia, Monographiae, 2. Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit.

- Evans, Arthur John (1894). "Primitive Pictographs and Script from Crete and the Peloponnese". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. XIV: 270–372. doi:10.2307/623973. JSTOR 623973. S2CID 163720432.

- —— (1901). "Minoan Civilization at the Palace of Knosses" (PDF). Monthly Review.

- —— (1906A) [1905]. Essai de classification des Époques de la civilization minoenne: résumé d'un discours fait au Congrès d'Archéologie à Athènes (Revised ed.). London: B. Quaritch.

- —— (1906B). The prehistoric tombs of Knossos: I. The cemetery of Zapher Papoura, with a comparative note on a chamber-tomb at Milatos. II. The Royal Tomb at Isopata. Archaeologia 59 (1905) pages 391–562. London: B. Quaritch.

- —— (1909). Scripta Minoa: The Written Documents of Minoan Crete: with Special Reference to the Archives of Knossos. Vol. I: The Hieroglyphic and Primitive Linear Classes: with an account of the discovery of the pre-Phoenician scripts, their place in the Minoan story and their Mediterranean relatives: with plates, tables and figures in the text. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- —— (1912). "The Minoan and Mycenaean Element in Hellenic Life". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 32: 277–287. doi:10.2307/624176. JSTOR 624176. S2CID 163279561.

- —— (1914). "The 'Tomb of the Double Axes' and Associated Group, and the Pillar Rooms and Ritual Vessels of the 'Little Palace' at Knossos". Archaeologia. 65: 1–94. doi:10.1017/s0261340900010833.

- ——. The Palace of Minos (PM): a comparative account of the successive stages of the early Cretan civilization as illustrated by the discoveries at Knossos. London: MacMillan and Co.

- —— (1921). PM. Vol. I: The Neolithic and Early and Middle Minoan Ages.

- —— (1928A). PM. Vol. II Part I: Fresh lights on origins and external relations: the restoration in town and palace after seismic catastrophe towards close of M. M. III and the beginnings of the New Era.

- —— (1928B). PM (PDF). Vol. II Part II: Town-Houses in Knossos of the New Era and restored West Palace Section, with its state approach.

- —— (1930). PM. Vol. III: The great transitional age in the northern and eastern sections of the Palace: the most brilliant record of Minoan art and the evidences of an advanced religion.

- —— (1935A). PM. Vol. IV Part I: Emergence of outer western enceinte, with new illustrations, artistic and religious, of the Middle Minoan Phase, Chryselephantine "Lady of Sports", "Snake Room" and full story of the cult Late Minoan ceramic evolution and "Palace Style".

- —— (1935B). PM. Vol. IV Part II: Camp-stool Fresco, long-robed priests and beneficent genii, Chryselephantine Boy-God and ritual hair-offering, Intaglio Types, M.M. III – L. M. II, late hoards of sealings, deposits of inscribed tablets and the palace stores, Linear Script B and its mainland extension, Closing Palatial Phase, Room of Throne and final catastrophe.

- Evans, Joan (1936). PM. Vol. Index to the Palace of Minos.

- —— (1952). Scripta Minoa: The Written Documents of Minoan Crete: with special reference to the archives of Knossos. Vol. II: The Archives of Knossos: clay tablets inscribed in linear script B: edited from notes, and supplemented by John L. Myres. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Gere, Cathy (2009). Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226289540.

- Landenius Enegren, Hedvig. The People of Knossos: prosopographical studies in the Knossos Linear B archives (Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2008) (Boreas. Uppsala studies in ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern civilizations, 30).

- MacDonald, Colin (2005). Knossos. Lost Cities of the Ancient World. London: Folio Society.

- —— (2003). "The Palace of Minos at Knossos". Athena Review. 3 (3). Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- MacDonald, Colin (2012). "Knossos". In Cline, Eric (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford University Press. pp. 529–542. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199873609.013.0040. ISBN 978-0199873609.

- MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander (2000). Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. New York: Hill and Wang (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). ISBN 9780809030354.

- Pendlebury, JDS; Evans, Arthur (Forward) (2003) [1954]. A handbook to the palace of Minos at Knossos with its dependencies. Oxford; Belle Fourche, SD: Oxford University Press; Kessinger Publishing Company.

- Whitelaw, Todd (2000). "Beyond the palace:A century of investigation at Europe's oldest city". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies: 223, 226.

External links

edit- "Knossos Tourist Information Page". Knossos-Palace.

- Swindale, Ian. "Minoan Crete website: Knossos Pages".

- "The Palace of Knossos". Odyssey: Adventures in Archaeology. odysseyadventures.ca. 2012.