The Turán graph, denoted by , is a complete multipartite graph; it is formed by partitioning a set of vertices into subsets, with sizes as equal as possible, and then connecting two vertices by an edge if and only if they belong to different subsets. Where and are the quotient and remainder of dividing by (so ), the graph is of the form , and the number of edges is

| Turán graph | |

|---|---|

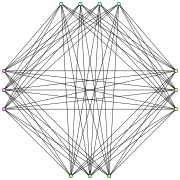

The Turán graph T(13,4) | |

| Named after | Pál Turán |

| Vertices | |

| Edges | ~ |

| Radius | |

| Diameter | |

| Girth | |

| Chromatic number | |

| Notation | |

| Table of graphs and parameters | |

- .

For , this edge count can be more succinctly stated as . The graph has subsets of size , and subsets of size ; each vertex has degree or . It is a regular graph if is divisible by (i.e. when ).

Turán's theorem

editTurán graphs are named after Pál Turán, who used them to prove Turán's theorem, an important result in extremal graph theory.

By the pigeonhole principle, every set of r + 1 vertices in the Turán graph includes two vertices in the same partition subset; therefore, the Turán graph does not contain a clique of size r + 1. According to Turán's theorem, the Turán graph has the maximum possible number of edges among all (r + 1)-clique-free graphs with n vertices. Keevash & Sudakov (2003) show that the Turán graph is also the only (r + 1)-clique-free graph of order n in which every subset of αn vertices spans at least edges, if α is sufficiently close to 1.[1] The Erdős–Stone theorem extends Turán's theorem by bounding the number of edges in a graph that does not have a fixed Turán graph as a subgraph. Via this theorem, similar bounds in extremal graph theory can be proven for any excluded subgraph, depending on the chromatic number of the subgraph.

Special cases

editSeveral choices of the parameter r in a Turán graph lead to notable graphs that have been independently studied.

The Turán graph T(2n,n) can be formed by removing a perfect matching from a complete graph K2n. As Roberts (1969) showed, this graph has boxicity exactly n; it is sometimes known as the Roberts graph.[2] This graph is also the 1-skeleton of an n-dimensional cross-polytope; for instance, the graph T(6,3) = K2,2,2 is the octahedral graph, the graph of the regular octahedron. If n couples go to a party, and each person shakes hands with every person except his or her partner, then this graph describes the set of handshakes that take place; for this reason, it is also called the cocktail party graph.

The Turán graph T(n,2) is a complete bipartite graph and, when n is even, a Moore graph. When r is a divisor of n, the Turán graph is symmetric and strongly regular, although some authors consider Turán graphs to be a trivial case of strong regularity and therefore exclude them from the definition of a strongly regular graph.

The class of Turán graphs can have exponentially many maximal cliques, meaning this class does not have few cliques. For example, the Turán graph has 3a2b maximal cliques, where 3a + 2b = n and b ≤ 2; each maximal clique is formed by choosing one vertex from each partition subset. This is the largest number of maximal cliques possible among all n-vertex graphs regardless of the number of edges in the graph; these graphs are sometimes called Moon–Moser graphs.[3]

Other properties

editEvery Turán graph is a cograph; that is, it can be formed from individual vertices by a sequence of disjoint union and complement operations. Specifically, such a sequence can begin by forming each of the independent sets of the Turán graph as a disjoint union of isolated vertices. Then, the overall graph is the complement of the disjoint union of the complements of these independent sets.

Chao & Novacky (1982) show that the Turán graphs are chromatically unique: no other graphs have the same chromatic polynomials. Nikiforov (2005) uses Turán graphs to supply a lower bound for the sum of the kth eigenvalues of a graph and its complement.[4]

Falls, Powell & Snoeyink (2003) develop an efficient algorithm for finding clusters of orthologous groups of genes in genome data, by representing the data as a graph and searching for large Turán subgraphs.[5]

Turán graphs also have some interesting properties related to geometric graph theory. Pór & Wood (2005) give a lower bound of Ω((rn)3/4) on the volume of any three-dimensional grid embedding of the Turán graph.[6] Witsenhausen (1974) conjectures that the maximum sum of squared distances, among n points with unit diameter in Rd, is attained for a configuration formed by embedding a Turán graph onto the vertices of a regular simplex.[7]

An n-vertex graph G is a subgraph of a Turán graph T(n,r) if and only if G admits an equitable coloring with r colors. The partition of the Turán graph into independent sets corresponds to the partition of G into color classes. In particular, the Turán graph is the unique maximal n-vertex graph with an r-color equitable coloring.

Notes

editReferences

edit- Chao, C. Y.; Novacky, G. A. (1982). "On maximally saturated graphs". Discrete Mathematics. 41 (2): 139–143. doi:10.1016/0012-365X(82)90200-X.

- Falls, Craig; Powell, Bradford; Snoeyink, Jack (2003). "Computing high-stringency COGs using Turán type graphs" (PDF).

- Keevash, Peter; Sudakov, Benny (2003). "Local density in graphs with forbidden subgraphs" (PDF). Combinatorics, Probability and Computing. 12 (2): 139–153. doi:10.1017/S0963548302005539. S2CID 17854032.

- Moon, J. W.; Moser, L. (1965). "On cliques in graphs". Israel Journal of Mathematics. 3: 23–28. doi:10.1007/BF02760024. S2CID 9855414.

- Nikiforov, Vladimir (2007). "Eigenvalue problems of Nordhaus-Gaddum type". Discrete Mathematics. 307 (6): 774–780. arXiv:math.CO/0506260. doi:10.1016/j.disc.2006.07.035.

- Pór, Attila; Wood, David R. (2005). "No-three-in-line-in-3D". Proc. Int. Symp. Graph Drawing (GD 2004). Lecture Notes in Computer Science no. 3383, Springer-Verlag. pp. 395–402. doi:10.1007/b105810. hdl:11693/27422.

- Roberts, F. S. (1969). Tutte, W.T. (ed.). "On the boxicity and cubicity of a graph". Recent Progress in Combinatorics: 301–310.

- Turán, P. (1941). "Egy gráfelméleti szélsőértékfeladatról (On an extremal problem in graph theory)". Matematikai és Fizikai Lapok. 48: 436–452.

- Witsenhausen, H. S. (1974). "On the maximum of the sum of squared distances under a diameter constraint". American Mathematical Monthly. 81 (10): 1100–1101. doi:10.2307/2319046. JSTOR 2319046.