This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

An ice cream float or ice cream soda, also known as an ice cream spider in Australia and New Zealand,[1] is a chilled beverage that consists of ice cream in either a soft drink or a mixture of flavored syrup and carbonated water.

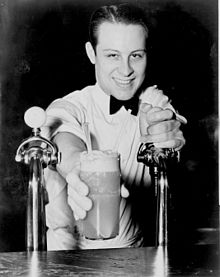

A New York World-Telegram newspaper photo of a soda jerk passing ice cream soda between two soda fountains in 1936 | |

| Alternative names | Ice cream soda, Coke float, root beer float, spider |

|---|---|

| Type | Dessert |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Region or state | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Created by | Robert McCay Green |

| Main ingredients | Ice cream, syrup and soft drink or carbonated water |

When root beer (sarsaparilla for Australia and New Zealand) and vanilla ice cream are used, the beverage is typically referred to as a root beer (sarsaparilla) float (United States[2] and Canada). A close variation is the coke float, using cola.

History

editThe ice cream float was invented by Robert M. Green in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1874 during the Franklin Institute's semicentennial celebration. The traditional story is that, on a particularly hot day, Green ran out of ice for the flavored drinks he was selling and instead used vanilla ice cream from a neighboring vendor, inventing a new drink.[3]

His own account, published in Soda Fountain magazine in 1910, states that while operating a soda fountain at the celebration, he wanted to create a new treat to attract customers away from another vendor who had a larger, fancier soda fountain. After some experimentation, he decided to combine ice cream and flavored soda. During the celebration, he sold vanilla ice cream with soda and a choice of 16 flavored syrups. The new treat was a sensation and soon other soda fountains began selling ice cream floats. Green's will instructed that "Originator of the Ice Cream Soda" was to be engraved on his tombstone.[4]

There are at least three other claimants for the invention of the root beer (sarsaparilla)float: Fred Sanders,[5] Philip Mohr,[5][6] and George Guy, one of Robert Green's own employees.[7] Guy claimed to have absentmindedly mixed ice cream and soda in 1872, much to his customers' delight.[8]

Regional names

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

In Australia and New Zealand, an ice cream float is known as a "spider" because once the carbonation hits the ice cream it forms a spider web-like reaction. It is traditionally made using either lime or pink cream soda.[9][10][11]

In the UK and Ireland, it is usually referred to as an "ice-cream float" or simply a "float," as "soda" is usually taken to mean soda water. Sweetened carbonated drinks are instead collectively called "soft drinks," "(fizzy) pop," or "fizzy juice."

In Mexico, it is known as "helado flotante" ("floating ice cream") or "flotante". In El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Colombia, it is called "vaca negra" (black cow); in Brazil, "vaca preta"; and in Puerto Rico, a "black out".

In the United States, an "ice cream soda" typically refers to the drink containing soda water, syrup, and ice cream, whereas a "float" is generally ice cream in a soft drink (usually root beer).

Variations

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

Variations of ice cream floats are as countless as the varieties of drinks and the flavors of ice cream, but some have become more prominent than others. Some of the most popular are described below:

Butterbeer

editIn 2014, The Wizarding World of Harry Potter themed area at the Universal Orlando debuted the drink composed of the ingredients brown sugar and butter syrup mixed with cream soda and whipped cream based on the originally fictional drink served at Hogsmeade. In 2016, Starbucks debuted the Smoked Butterbeer Frappuccino Latte.[12]

Beer float

editA beer float is made of Guinness stout, chocolate ice cream, and espresso.[13] Although the Shakin' Jesse version[14] is blended into more of a milkshake consistency, most restaurant bars can make the beer float version. When making at home, the beer and espresso should be very cold so as to not melt the ice cream

Boston cooler

editToday, a Boston cooler is typically composed of Vernors ginger ale and vanilla ice cream.[15]

The first reference to a Boston cooler appears in the St. Louis Post Dispatch where a New York bartender claimed to have coined the phrase for a summer cocktail of sarsaparilla and ginger ale. In the 1910s, the term was applied in soda fountains and ice cream parlors to a scoop of ice cream served in a melon half. The name was also applied to a number of different ice-cream float combinations, including root beer, though ginger ale became the most common soft drink component. [16]

By the 1880s a version of the Boston cooler was being served in Detroit by Sanders Confectionery, made with Sanders' ice cream and Vernors.[15] Originally, a drink called a Vernors Cream was served as a shot or two of sweet cream poured into a glass of Vernors. Later, vanilla ice cream was substituted for the cream and blended like a milkshake. The local myth, that it was named after Detroit's Boston Boulevard, is belied by the fact that Boston Boulevard did not exist at the time.[17][18][19]

It remains a popular summer drink in the Detroit area.[15]

Chocolate ice cream soda

editThis ice cream soda starts with approximately 1 oz of chocolate syrup, then several scoops of chocolate ice cream in a tall glass. Unflavored carbonated water is added until the glass is filled and the resulting foam rises above the top of the glass. The final touch is a topping of whipped cream and usually, a maraschino cherry. This variation of ice cream soda was available at local soda fountains and nationally, at Dairy Queen stores for many years.[citation needed]

A similar soda made with chocolate syrup but vanilla ice cream is sometimes called a "black and white" ice cream soda.[citation needed]

Cream soda

editIn Japan, an ice cream float known as a cream soda is made with vanilla ice cream and melon soda, often topped with a single maraschino cherry.[20]

Helado flotante

editIn Mexico, popular versions are made from coca-cola with coconut and Kahlúa ice cream, from chocolate coca-cola with vanilla ice cream, and from red wine with lemon ice cream.[21]

Nectar soda

editThis variant is popular in New Orleans and parts of Ohio, made with a syrup consisting of equal parts almond and vanilla syrups mixed with sweetened condensed milk and a touch of red food coloring to produce a pink, opalescent syrup base for the soda.[22][23]

Purple cow

editIn the context of ice cream soda, a purple cow is vanilla ice cream in purple grape soda. The Purple Cow,[24] a restaurant chain in the southern United States, features this and similar beverages. In a more general context, a purple cow may refer to a non-carbonated grape juice and vanilla ice cream combination. Grapico, a brand of grape soda bottled in Birmingham, Alabama, is ubiquitously linked to ice cream floats in that state.

The soda is named after Gelett Burgess's 1895 nonsense poem Purple Cow.

Root beer float

editAlso known as a "black cow"[25][26] or "brown cow",[27] the root beer float is traditionally made with vanilla ice cream and root beer, but it can also be made with other ice cream flavors. Frank J. Wisner, owner of Colorado's Cripple Creek Brewing, is credited with creating the first root beer float on August 19, 1893. The similarly flavored soft drink birch beer may also be used instead of root beer.

In the United States and Canada, the chain A&W Restaurants are well known for their root beer floats. The definition of a black cow varies by region. For instance, in some localities, a "root beer float" has strictly vanilla ice cream; a float made with root beer and chocolate ice cream is a "chocolate cow" or a "brown cow". In some places a "black cow" or a "brown cow" was made with cola instead of root beer.

In 2008, the Dr Pepper Snapple Group introduced its Float beverage line. This includes A&W Root Beer, A&W Cream Soda and Sunkist flavors which attempt to simulate the taste of their respective ice cream float flavors in a creamy, bottled drink.

Strawberry ice cream soda

editThis drink is prepared similarly to a chocolate ice cream soda, but with strawberry syrup and strawberry (or vanilla) ice cream used instead.[citation needed]

Vaca amarela or vaca dourada

editIn Brazil, a vaca amarela (yellow cow) or vaca dourada (golden cow) is an ice cream soda combination of vanilla ice cream and orange or guaraná soda, respectively.[citation needed]

Vaca-preta

editAt least in Brazil and Portugal, a non-alcoholic ice cream soda made by combining vanilla or chocolate ice cream and Coca-Cola is known as vaca-preta ("black cow").[28]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "spider, n.4" The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Wenzl, Megan. "The Hidden History of Root Beer Floats in Chicago". Chicago Eater. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "Soda beverages in Philadelphia". American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record. 48: 163. 1906.

- ^ "Ice Cream Soda a New Drink". The Soda Fountain. 20. D. O. Haynes: 66. 1921.

- ^ a b Sundae Best: a history of soda fountains by Anne Cooper Funderburg; Popular Press, 2002

- ^ The Three Principal Claimants for the Invention of Ice Cream Soda; Soda Fountain, Vol. 18; November 1913

- ^ "Ice Cream Soda Invented By Seattle Pioneer" Seattle Times May 19, 1965. p.40

- ^ "Toddler Making Ice Cream Soda". corbisimages.com. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Spider drink story has legs". www.heraldsun.com.au. June 3, 2011.

- ^ "Macquarie Dictionary entry for 'spider'". Macquarie Online Dictionary. 25 October 2023.

- ^ Laura Macfehin (September 7, 2019). "What is root beer, anyway?". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ Barbour, Shannon (Jan 17, 2018). "Starbucks Is Bringing Back Its Smoked Butterscotch Latte (Which Tastes Just Like Butterbeer)". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved September 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Thirsty Reader: A Guinness Milkshake". Kitchn.

- ^ "Emeryville | Rudy's Can't Fail Cafe". Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ a b c Fenech, Jeremy (September 26, 2012). "What is a Boston Cooler?". wcrz. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Newman, Eli (July 25, 2016). "CuriosiD: What's the Origin of the Boston Cooler?". WDET.org. WDET and Wayne State University. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ "Griffin, Holly, "FIVE THINGS: About coolers" Detroit Free Press (August 31, 2007)". Accessmylibrary.com. August 31, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ ""Daily TWIP: Ice Cream Soda Day", Nashua Telegraph (June 20, 2008)". Nl.newsbank.com. June 20, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ "History"Archived September 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Historic Boston Edison Association

- ^ Garcia, Krista (2018-12-18). "The Emerald Green Drink of 1970s Japan". TASTE. Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ^ https://www.timeoutmexico.mx/ciudad-de-mexico/restaurantes-cafes/top-5-flotantes [bare URL]

- ^ Woellert, D. (2017). Cincinnati Candy: A Sweet History. American Palate (in Italian). Arcadia Publishing (SC). pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-1-4671-3795-9. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ Goldstein, D.; Mintz, S. (2015). The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. Oxford Companions. Oxford University Press. p. pt848. ISBN 978-0-19-931362-4. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ The Purple Cow

- ^ "The Milwaukee Journal - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Letters, Dec. 14, 1931". Time. December 14, 1931 – via content.time.com.

- ^ "The Cedartown Standard - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ See article Vaca preta at the Wikipedia in Portuguese. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

Sources

edit- Funderburg, Anne Cooper. "Sundae Best: A History of Soda Fountains" (2002) University of Wisconsin Popular Press. ISBN 0-87972-853-1.

- Gay, Cheri Y. (2001). Detroit Then and Now, p. 5. Thunder Bay Press. ISBN 1-57145-689-9.

- Bulanda, George; Bak, Richard; and Ciavola, Michelle. The Way It Was: Glimpses of Detroit's History from the Pages of Hour Detroit Magazine, p. 8. Momentum Books. ISBN 1-879094-71-1.

- Houston, Kay. "Of soda fountains and ice cream parlors." (February 11, 1996) The Detroit News.

- Alissa Ozols (2008) San Francisco.

External links

edit- Bartending/Cocktails/Glossary at Wikibooks

- Media related to Ice cream soda at Wikimedia Commons

- The dictionary definition of ice cream soda at Wiktionary