The Colonial Hotel is a historic building in Seattle located at 1119-1123 at the southwest corner of 1st Avenue and Seneca Streets in the city's central business district. The majority of the building recognizable today was constructed in 1901 over a previous building built in 1892-3 that was never completed to its full plans.

Colonial Hotel | |

The Colonial Hotel, September 2007 | |

| Location | 1119-1123 1st Ave., Seattle, Washington |

|---|---|

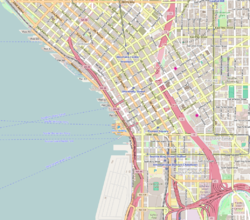

| Coordinates | 47°36′22″N 122°20′11″W / 47.60611°N 122.33639°W |

| Built | 1892, 1901 |

| Architect | Max Umbrecht |

| Architectural style | Federal Style |

| NRHP reference No. | 82004232[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 29, 1982 |

Built as a response to the boom created by the Yukon Gold Rush, the Colonial operated as a single resident occupancy hotel into the 1970s and in the 1980s it was restored into apartments and connected to its southern neighbor, the Grand Pacific Hotel. Both were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982 and later became Seattle city landmarks. Today they are known collectively as the Colonial Grand Pacific.

History

editFollowing the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, the northward expansion of Seattle's business district from Pioneer Square, already in progress prior to the fire, took on a rapid pace. A quick glut of new office space and a shortage of building materials created by the boom however left many buildings incomplete and many more lots undeveloped as the economy began to cool in 1891. The 4-story Starr Building, built in 1890 on the west side of 1st Avenue between Spring and Seneca Streets, stood alone on the block until a second wave of construction began in 1892.

The Kenyons

editJacob Gardner Kenyon, a traveling ventriloquist and magician, first passed through Seattle in the early 1880s and with the ticket sales from his first show at Yesler Hall, purchased several lots on 1st Avenue before leaving town, purchasing even more on his second tour. The value of his property skyrocketed following the great fire but he refused all offers to lease it.[2] In mid-1892, Kenyon commissioned prominent architect John Parkinson to design a six-story building of granite and white pressed brick to be built on his corner lot adjoining the Starr Building. John McConnell won the contract for brickwork while G.W. Webster was put in charge of the carpentry.[3] Construction began in July 1892 on the basement levels but was paused multiple times, and was ultimately only completed to the first floor on 1st Avenue, with Kenyon citing the lack of demand for office or lodging space as well as the benefit of allowing the foundation to settle.[4] Kenyon died on December 22, 1892, without finishing the building and the property, along with all of Kenyon's Seattle holdings was willed to his son, Benjamin Kenyon. Litigation involving unpaid loans and under-compensated heirs soon followed along with the Panic of 1893, preventing the completion of the building for the rest of the decade. During this time the ground floor, designed to be split into 3 storefronts, was mostly occupied by the Seattle Outfitting Company, a home furnishings store, and the salesroom of the Seattle Woolen Mill Company,[5] specializing in Flannel blankets for Yukon miners while the two basement levels were rented out for storage.[6]

Clise, Chapin and Collins

editIn December 1900, Prominent Seattle businessman and attorney James Clise, representing Charles R. Collins (a civil engineer) and Herman Chapin (president of the Boston National Bank), purchased the incomplete Kenyon Building and one other nearby lot from the Kenyon Estate for $430,000. Collins and Chapin immediately made plans to complete the building to house a hotel to meet the demands of a city once again booming as a result of the Yukon Gold Rush.[7][page needed] They commissioned architect Max Umbrecht, who had come to Seattle from Syracuse, New York earlier in the year under the employ of L.C. Smith. He designed several buildings for Smith's Pioneer Square properties and would go on to design several more for Clise and many more buildings in Seattle over the next two decades. For this project Umbrecht chose an eclectic Federal motif executed with buff brick trimmed with stone and glazed terra cotta for the top 3 floors of the building that would be built on top of the existing Kenyon building and inspire the hotel to be called the Colonial. The original design included a parapet above the cornice composed of open balustrades and a central pediment bearing the Colonial name, long since lost to deterioration. The building's retail tenants were evicted and a building permit was issued on January 20, 1901.[8] Work was completed by September when new ground floor tenants began advertising and the hotel opened with Florence M. Burke as proprietor.[9] Among the earliest ground floor tenants in the completed building were the Abbo Medical & Surgical Institute,[10] the Rainier Hardware Co.,[11] and the Keystone Liquor Co.[12] In 1906, Clise sold the hotel to Schwabacher Hardware Company treasurer Sigmund Aronson and prominent local attorney Harold Preston for $180,000.[13]

Weyerhaeuser

editBy the 1950s the businesses in the neighborhood began to reflect a seedier nature as Seattle's commercial core had long since moved north. During this time the ground floor of the Colonial was occupied by second-hand shops and the Sportsland Arcade, which several times had been raided by police for showing and transporting adult films.[14] In the mid 1960s, while many small downtown hotels in Seattle were being closed by the city's Nuisance abatement board, The Colonial Hotel, recently purchased along with its neighbor the Grand Pacific Hotel by the Kerry Timber Company and operated under lease by Tetsuo Kuramoto, was deemed to still be in fine condition and was allowed to stay open while the Grand Pacific was shuttered.[15] The Colonial would only operate as a hotel for a few more years; its furnishings were sold at auction in 1972.[16] Beginning in the late 70s, The Colonial and other historic buildings in the area were restored and redeveloped by Cornerstone Development Co, a subsidiary of Weyerhaeuser (which had absorbed the Kerry Timber Company) as part of the Waterfront Center project, which combined new construction with older buildings restored for housing.[17][page needed] During restoration, The Colonial Hotel was interconnected with the Grand Pacific Hotel to the south and the complex became known as the Colonial Grand Pacific Apartments. The Colonial Hotel was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 13, 1982.[18]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Against Kenyon Estate: Big Foreclosure Suits Instituted In Superior Court". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. December 14, 1899. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "The New Buildings: Kenyon Will Extend Front Street Retail District". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. June 6, 1892. p. 8. Retrieved January 14, 2021 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "New Schoolhouses: Buildings Finished At South Seattle and Duwamish". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. October 10, 1892. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Seattle Woolen Mill Co. [Advertisement]". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. August 26, 1893. p. 8. Retrieved June 21, 2021 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- ^ "Storage in New Brick Building at Low Rates [Classified Ad]". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. August 26, 1893. p. 6. Retrieved June 21, 2021 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- ^ Ballaine, John E. (December 22, 1900). "Real Estate and Building: A Year of Great Progress". The Seattle Daily Times.

- ^ "The City Hall [Building Permits Issued]". The Seattle Daily Times. January 21, 1901. p. 12.

- ^ Polk's Seattle City Directory (15th ed.). Seattle: Polk's Seattle Directory Co. 1901. p. 281. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ "Abbo's Success [Advertisement]". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. September 27, 1901. p. 2. Retrieved June 21, 2021 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- ^ "Rainier Hardware Co. [Advertisement]". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. November 9, 1901. p. 3. Retrieved June 21, 2021 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- ^ "Keystone Liquor Co. [Advertisement]". The Seattle Star. December 23, 1903. p. 7. Retrieved June 21, 2021 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- ^ "Five Big Realty Sales Made in a Day". The Seattle Sunday Times. November 18, 1906. p. 24.

- ^ "City Council: Cafe-Dance License Is Opposed". The Seattle Daily Times. January 3, 1956. p. 17.

- ^ "Two More of Old Seattle Hotels Closing". The Seattle Times. October 28, 1966. p. 2.

- ^ "Public Auction...Colonial Hotel, 1st and Seneca [Advertisement]". The Seattle Times. March 11, 1972. p. B13.

- ^ "Five Downtown Blocks to Be Renovated by Weyerhaeuser". The Seattle Times. March 20, 1980.

- ^ "Seattle Area Represented Among New Entries to National Register". The Seattle Times. July 4, 1982. p. D6.