Commonwealth Stadium is an open-air, multipurpose stadium located in the McCauley neighbourhood of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It has a seating capacity of 56,302, making it the largest open-air stadium in Canada. Primarily used for Canadian football, it also hosts athletics, soccer, rugby union and concerts.

| |

Commonwealth Stadium in October 2024. | |

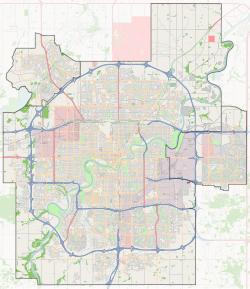

| Location | 11000 Stadium Road Edmonton, Alberta, Canada |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 53°33′30″N 113°28′30″W / 53.55833°N 113.47500°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | City of Edmonton |

| Capacity |

|

| Record attendance | 66,835 (U2 360° Tour) |

| Surface |

|

| Construction | |

| Opened | July 15, 1978 |

| Renovated | 2001, 2008 |

| Expanded | 1982, 2013 |

| Construction cost | C$20.9 million ($89.7 million in 2023 dollars[1]) Expansion: 1982: CA$11 million ($31.5 million in 2023 dollars[1]) 2013: CA$12 million ($15.3 million in 2023 dollars[1]) Renovations: 2001: $24 million ($38.6 million in 2023 dollars[1]) 2008: CA$112 million ($154 million in 2023 dollars[1]) Total cost: $296.8 million in 2021 dollars |

| Architect | Bell, McCulloch, Spotowski and Associates |

| Tenants | |

| |

Construction commenced in 1975 and the venue opened ahead of the 1978 Commonwealth Games, hence its name. The stadium replaced the adjacent Clarke Stadium as the home of the Edmonton Eskimos[a] of the Canadian Football League that same year. It received a major expansion ahead of the 1983 Summer Universiade, when it reached a capacity of 60,081. Commonwealth Stadium has hosted five Grey Cups, the CFL's championship game.

Soccer tournaments include nine FIFA World Cup qualification matches with the Canadian men's national soccer team, two versions of the invitational Canada Cup, the 1996 CONCACAF Men's Pre-Olympic Tournament, the 2002 FIFA U-19 Women's World Championship and the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup, the 2014 FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup and the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup. FC Edmonton played its Canadian Championship matches at Commonwealth Stadium from 2011 to 2013.

Other events at the stadium include the 2001 World Championships in Athletics, the 2006 Women's Rugby World Cup and three editions of the Churchill Cup.

History

editPrior to Commonwealth Stadium, the main stadium in Edmonton was Clarke Stadium, which opened in 1939 and was built on a 15-hectare (38-acre) plot of land. Work on applying to host the 1978 Commonwealth Games started in the early 1970s. With both federal, provincial and city funding backing the bid, it called for a massive renovation of the city's various sporting venues. The original plans called for Clarke Stadium to be rebuilt and expanded to host the athletics events. By 1974 there was consensus that Clarke Stadium would not be sufficient and that an all-new stadium should be built. Several locations and sizes were discussed, with Edmonton City Council in January 1975 landing on building a 40,000-seat venue next to Clarke Stadium.[2] The venue was designed by Ragan, Bell, McManus Consultants.[3] The city also decided to build additional new venues: Kinsmen Aquatic Centre and Argyll Velodrome.[2] They based their design on Jack Trice Stadium in the US city of Ames, Iowa.[4]

Part of the public support for the stadium came from it being built to also support being used by the Eskimos (the Elks' name until 2020). The plans were met with opposition from local residents. There were also discussions regarding the necessity of a $50,000 royal retirement room and the allocation of training and office space to the Eskimos. The largest discussion was related to whether the stadium needed a roof or dome. As the roof would cost $18.2 million, there was limited public support, and the stadium was built without one.[2] In an attempt to further the roof process, the Eskimos offered to pay $1.6 million towards the roof.[4] The Commonwealth Games did not permit an enclosed stadium, so the design would have to call for the roof to be added afterwards. Among the opponents of the roof was Commonwealth Games Foundation President Maury Van Vliet, who said experience from construction of the Olympic Stadium in Montreal showed the necessity of building a simple structure. An alternative design, which would have cost an additional $7.3 million, was launched by the Eskimos in August 1975, but rejected by the city council.[3] A major concern for the city council was the large cost overruns being experienced in Montreal at the time.[4]

Excavation started in December 1974 and saw the removal of 380,000 cubic metres (500,000 cu yd) of earthwork. A local action committee, Action Edmonton, demanded in early 1975 that construction be halted and the venue relocated. The city estimated that this would cost an additional $2.5 million and delay the process with eight months.[4] The decision to not enclose the stadium was taken on December 10, 1975.[3] The venue was thus not designed to allow a roof, air-filled or stiff, to be retrofitted.[5] The venue was built on the former site of the Rat Creek Dump and the Williamson Slaughter House. During excavation, remains from the dump were struck, resulting in archaeological surveys being carried out.[4] Construction of the Edmonton LRT's inaugural line (later named the Capital Line) commenced in 1974 and was opened in time for the Commonwealth Games, which allowed spectators to take the LRT from Stadium station to downtown Edmonton.[6]

Construction of the stadium was completed within budget and time.[2] When the venue opened it had a capacity for 42,500 and a natural grass turf.[7] Unlike most other major stadiums in Canada, Commonwealth Stadium elected for a natural grass turf.[2] The original configuration included 39,384 bucket seats and 3,200 bench seating on the north end. The venue was officially opened on July 15, 1978, in an event which attracted 15,000 spectators.[4] The venue went through a slight expansion in 1980, when the seating capacity was increased to 43,346.[7] Additional proposals for a roof, ranging from $10 to $32 million in cost, were presented in 1979, but since then the discussion of covering the stadium died out.[4]

Edmonton was selected to host the 1983 Summer Universiade, and in 1981 the city council approved an $11 million upgrade to the venue, which added a further 18,000 seats to the upper tiers and the north end zone;[4] this gave a capacity of 59,912 in 1982 and 60,081 from 1983.[7] For special events, such as the Grey Cup, additional seating could be added. This made it the second-largest stadium in Canada, after Montreal's Olympic Stadium, and the largest without a dome.[2] After Winnipeg Stadium, home of the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, installed AstroTurf on their field for the 1988 CFL season, the stadium was the last in the CFL to have a natural grass surface (a few teams from the CFL's American expansion in the 1990s notwithstanding); it would have this distinction for the next 21 years.

Ahead of the 2001 World Championships in Athletics, the stadium received a $24-million facelift. Major investments included a new façade, an enlargement of the concourse, improved lighting, a new scoreboard and an all-new all-weather running track.[4] Ahead of the 2008 season the stadium underwent a reconfiguration, reducing its capacity to 59,537.[7] For the nine seasons prior to 2010, the natural turf was replaced eight times, costing $50,000 each time.[8] The natural grass turf was replaced with FieldTurf Duraspine Pro in May 2010, making the Eskimos the last CFL team to switch to artificial turf (and made all fields in the CFL having artificial turf; this would last for six seasons),[9] and the last team to play on grass until the Toronto Argonauts began playing at BMO Field for the 2016 season. The investment cost $2.6 million and was split evenly between the city and the Eskimos.[8] The work included the removal of 12,400 cubic metres (440,000 cu ft) of soil,[9] and the turf has a life expectancy of 8 to 10 years. It will cost $500,000 to replace. The reasons for the replacement were to reduce injuries, reduce the need for watering and fertilizer, allow a green turf for the entire season, including at Grey Cups (when the weather is especially cold in Edmonton), allow the venue to host more events, as concerts and the like will not damage the field, and that turf is recycled and recyclable.[8]

Commonwealth Stadium underwent a $112-million facelift starting in 2009. The main investment was a field house, new locker rooms, a hosting area and two floors of office space.[10] The complex, named the Commonwealth Community Recreation Centre and designed by MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller Architects and HIP Architects, also has an aquatic centre and a fitness centre.[11] The complex was completed in February 2012.[12]

Following the 2010 Grey Cup, the program to replace the seating at the stadium commenced. All seating (which had been in place since the stadium's opening) was replaced with new and wider seats, and the color changed from red and orange to green and yellow—the Eskimos' colors. Approval of the $12 million upgrade was made by the city council on May 18, 2011, and it took 11 months to select a supplier, with installation starting in June 2012. The upgrade removed all bench seating, which had been in place in the corners and end zones, resulting in an all-seater stadium. Because of wider seats, 53 centimetres (21 in) wide instead of 48 centimetres (19 in), capacity for the venue as reduced to 56,302. The process reduced the number of seats in each row by one.[13] With the seating installed, the total investment in the venue exceeded $200 million.[14] Before the start of the 2014 CFL season, the track surface was stripped off, thus giving the football end zones a squared-off look; they were rounded off prior to this.[15]

On June 15, 2016, the Edmonton Eskimos announced a five-year field naming rights partnership with The Brick to name the field "The Brick Field at Commonwealth Stadium" during CFL events.[16]

The Edmonton Elks will not sell upper bowl tickets at Commonwealth Stadium for the 2024 CFL season, reducing the stadium's capacity to 31,000 seats.[17]

Facilities

editCommonwealth Stadium has a seating capacity of 56,302, in an all-seater configuration. The stadium has two twin-tier grandstands along each side, and single-tier stands on the corners and ends. The sides feature 44,032 seats, with the remaining 12,386 in the corners and ends. The side seats are 53 centimetres (21 in) wide and have a cup holder, a feature lacking on the narrower end zone seats. The seating is laid out in a colorized mosaic pattern, with dark green at the bottom, yellow in the middle and lighter green at the top. In the sides there are 14,203 dark green seats, 19,019 yellow seats and 10,810 light green seats. In the corner and end zones there are 8,672 dark green and 3,713 yellow seats.[13] There are 15 executive suites on the east stand, 7 on the west stand and 8 on the south end zone. There is a limited amount of covered seating on the upper sections of the lower tier on the sides; half of this section on the east stand is a media centre.[18]

The stadium has a Shaw Sports Turf Powerblade Elite 2.5S artificial turf system, installed in 2016 by GTR turf, which covers an area of 10,215 square metres (109,950 sq ft). It contains additional cushioning through the installation of an extra shock pad.[9] The turf lacks permanent line markings; this allows the markings to alternate between football and soccer.[19] Because of the running track, the corners of the end zones were partially cut. In 2014, the end zones were squared off.[20] The track and field segment consists of a Sportflex Super X all-weather running track manufactured by Mondo of Italy. The International Association of Athletics Federations has certified the stadium as a Class 1 venue, a certification only two other stadiums have in Canada: Moncton Stadium and Université de Sherbrooke Stadium.[21]

At Commonwealth Stadium complex is the Field House, an 8,400-square-metre (90,000 sq ft) three-storey training facility which includes a running track, a 64-by-64-metre (70 by 70 yd) artificial turf training field, a fitness and weight room, locker rooms and a running track.[12] It is part of the Commonwealth Community Recreation Centre, which also includes a 5,600-square-metre (60,000 sq ft) aquatics centre with a four-lane lap pool, water slides and a recreational pool; 2,800 square metres (30,000 sq ft) of administrative offices; and a 2,800-square-metre (30,000 sq ft) fitness centre. The building features a central lobby with each of the facilities in an annex. The centre has Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Silver certification.[11] Adjacent to Commonwealth Stadium lies Clarke Stadium; it seats 5,000 and is used as a training field and as the home ground of the Canadian Premier League side FC Edmonton until it was dissolved in 2022.[22]

The stadium is served by Stadium station of the Edmonton Light Rail Transit Capital Line. During Elks games, the service frequency is increased. The City of Edmonton and the Elks cooperate on the Green & Go program, which provides free transit rides to the venue from six park and ride lots throughout Edmonton. Any holder of a pre-purchased game ticket can travel free on the buses from these lots to Commonwealth Stadium. The program was initiated by the city to minimize parking and congestion in the stadium's neighbourhood. Game tickets are also valid fare on the LRT service from two hours prior to games to two hours after games. The city bans on-street parking in the vicinity of the stadium during games, excepting cars with residential permits.[23]

Events

editAthletics

editCommonwealth Stadium was the centrepiece of the 1978 Commonwealth Games, which were hosted from August 3 to 12. The games saw 1,474 athletes from 46 nations competed in 128 events. Canada conducted its all-time best performance, capturing 45 gold medals and 109 medals in total. Commonwealth Stadium hosted the athletics events,[2] which consisted of 38 events: 23 for male and 15 for female competitors,[citation needed] as well as the opening and closing ceremonies.[2]

The success and popularity of the Commonwealth Games resulted in Edmonton bidding for and being selected to host the 1983 Summer Universiade. Commonwealth Stadium was again selected to host the athletics events, in addition to the opening and closing ceremonies.[2] 24 male and 17 female athletics events were hosted.[citation needed] The games saw 2,400 participants from 73 countries, but did not attract the same public attention as the Commonwealth Games had.[2]

The 2001 World Championships in Athletics were held at Commonwealth Stadium between August 3 and 12, featuring 1677 participants from 189 nations.[citation needed]

Canadian football

editCommonwealth Stadium has been the home of the Canadian Football League's Edmonton Eskimos/Elks since the 1978 season.[2] In the 1977 season, the last whole season at Clarke, the Eskimos drew an average 25,324 spectators, filling up the venue to its capacity for seven of eight games.[24] For the 1979 season, they drew an average 42,540 spectators, selling out seven of eight games.[25] The all-time regular-season attendance record is 62,517, set against the Saskatchewan Roughriders on September 26, 2009.[26] 28 regular-season Edmonton Elks games have sold out at Commonwealth. With the laying of artificial turf in 2010, the team stopped training on Clarke Stadium and have since used Commonwealth Stadium as their training ground.[27]

|

|

The stadium has been host to the Grey Cup, the CFL's championship game, five times, in 1984, 1997, 2002, 2010, and 2018. Tickets to the 2010 Grey Cup were sold out prior to the start of the season. The game was spectated by a crowd of 63,317, the largest to attend the stadium.[62]

| Game | Date | Winning team | Score | Losing team | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72nd | November 18, 1984 | Winnipeg Blue Bombers (8) | 47–17 | Hamilton Tiger-Cats | 60,081 |

| 85th | November 16, 1997 | Toronto Argonauts (14) | 47–23 | Saskatchewan Roughriders | 60,431 |

| 90th | November 24, 2002 | Montreal Alouettes (5) | 25–16 | Edmonton Eskimos | 62,531 |

| 98th | November 28, 2010 | Montreal Alouettes (7) | 21–18 | Saskatchewan Roughriders | 63,317 |

| 106th | November 25, 2018 | Calgary Stampeders (8) | 27–16 | Ottawa Redblacks | 55,819 |

Soccer

edit- Edmonton Drillers

The Edmonton Drillers of the North American Soccer League, then the premier soccer league in Canada and the United States, was established in 1979 with the relocation of the Oakland Stompers. Bought by Peter Pocklington, the team chose to play its first three seasons at Commonwealth Stadium. The team played to home play-off matches during the 1980 season.[63] The Drillers averaged between 9,923 and 10,920 in their first three seasons.[64] After having lost $10.5 million in three years, Pocklington chose to relocate to Clarke Stadium for the 1982 season. This caused average attendance to plummet to 4,922 and the team was disbanded at the end of the year.[63]

| Season | Capacity | Average | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 42,500 | 9,923 | [64] |

| 1980 | 43,346 | 10,920 | [64] |

| 1981 | 43,346 | 10,632 | [64] |

- Canadian Soccer Association

In the past, because of its natural turf, Commonwealth Stadium has been a favored stadium for the Canadian Soccer Association to host national games. It has hosted 18 games of the Men's National Soccer Team and two of the Men's Under-20 National Team. The most intense period was between 1995 and 2000, when 13 A-team games were played. The A-team has played nine FIFA World Cup qualification and five friendly matches at Commonwealth. The record attendance of 51,936 was set when Canada tied Brazil 1–1 on June 5, 1994.[65]

The Canadian Soccer Association twice invited to the Canada Cup, a three- or four-way invitational international friendly tournament, with all matches hosted at Commonwealth Stadium. The 1995 Canada Cup featured Canada, Northern Ireland and Chile,[66] while the 1999 Canada Cup featured Canada U-23, Iran, Ecuador and Guatemala U-23.[67]

On November 16, 2021, the stadium hosted a third-round match in the CONCACAF 2022 FIFA World Cup qualifiers between Canada and Mexico; with a 2–1 victory, Canada defeated Mexico for the first time in 21 years, taking the lead in the pool. Due to the frigid Prairie temperatures of November, Canada Soccer tweeted that the stadium was "Canada's frozen fortress", while fans also nicknamed the field "Estadio Iceteca" or "The Iceteca", in reference to Mexico's home field Estadio Azteca. With a temperature of −9 °C at kickoff, it was the coldest game in Mexico national team history.[68][69][70]

| Dates | Tournament | Opponent | Score | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 27, 1980 | Friendly | New Zealand | 3–0 | — |

| June 16, 1983 | Friendly | Scotland | 0–3 | 10,240 |

| July 25, 1984 | Friendly | Chile | 0–0 | 6,137 |

| September 27, 1993 | 1994 FIFA World Cup qualification | Australia | 2–1 | 27,775 |

| June 5, 1994 | Friendly | Brazil | 1–1 | 51,936 |

| May 22, 1995 | 1995 Canada Cup | Northern Ireland | 2–0 | 12,112 |

| May 28, 1995 | 1995 Canada Cup | Chile | 1–2 | 17,047 |

| August 30, 1996 | 1998 FIFA World Cup qualification | Panama | 3–1 | 9,402 |

| October 10, 1996 | 1998 FIFA World Cup qualification | Cuba | 2–0 | 6,046 |

| October 13, 1996 | 1998 FIFA World Cup qualification | Cuba | 2–0 | 10,122 |

| June 1, 1997 | 1998 FIFA World Cup qualification | Costa Rica | 1–0 | 9,100 |

| October 12, 1997 | 1998 FIFA World Cup qualification | Mexico | 2–2 | 11,806 |

| June 2, 1999 | 1999 Canada Cup | Guatemala | 2–0 | 5,821 |

| June 4, 1999 | 1999 Canada Cup | Iran | 0–1 | 8,865 |

| June 6, 1999 | 1999 Canada Cup | Ecuador | 1–2 | 10,026 |

| July 16, 2000 | 2002 FIFA World Cup qualification | Trinidad and Tobago | 0–2 | 25,000 |

| September 4, 2004 | 2006 FIFA World Cup qualification | Honduras | 1–1 | 9,654 |

| October 15, 2008 | 2010 FIFA World Cup qualification | Mexico | 2–2 | 14,145 |

| May 28, 2013 | Friendly | Costa Rica | 0–1 | 8,102 |

| November 12, 2021 | 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Costa Rica | 1–0 | 48,806 |

| November 16, 2021 | 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Mexico | 2–1 | 44,212 |

Edmonton has hosted five international friendly matches and two FIFA Women's World Cup matches featuring the Canada women's national soccer team. Before the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup, the record attendance was 29,953 for a game on August 31, 2003, when Canada beat Mexico 8–0.[71] The attendance record was broken in 2015, when a record crowd of 53,058 saw Canada beat China 1–0 in the first match of the Women's World Cup.

| Date | Tournament | Opponent | Score | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 28, 1995 | Friendly | United States | 1–2 | — |

| August 31, 2003 | Friendly | Mexico | 8–0 | 29,953 |

| September 4, 2005 | Friendly | Germany | 3–4 | 8,812 |

| October 30, 2013 | Friendly | South Korea | 3–0 | 12,746 |

| October 25, 2014 | Friendly | Japan | 0–3 | 9,654 |

| June 6, 2015 | 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup | China | 1–0 | 53,058 |

| June 11, 2015 | 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup | New Zealand | 0–0 | 35,544 |

Canada and Commonwealth Stadium were host to the 1996 edition of the CONCACAF Men's Olympic Qualifying Tournament, which featured the Men's Under-23 National Team between 10 and 19 May.[72] The tournament drew crowds up to 19,401,[65] and saw Canada finish second to Mexico.[73] Canada played Australia, playing 2–2 at Commonwealth Stadium on 26 May. Canada lost 5–0 in Australia and fail to qualify.[74]

Edmonton co-hosted the inaugural 2002 FIFA U-19 Women's World Championship between August 17 and September 1 along with Vancouver and Victoria. Edmonton was the base of operations and featured 12 of the 26 matches. FIFA was originally skeptical to using such a large venue, especially for those matches which did not involve Canada. The 12 games drew a total 238,090 and an average 19,841 spectators. The final, which saw the United States defeat Canada 1–0 in extra time, was spectated by 47,784;[75] this remains a world-record attendance for youth-level women's soccer.[76]

Commonwealth Stadium was one of six Canadian venues selected to host the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup between June 30 and July 22. Nine of 52 matches were played in Edmonton, including a quarterfinal and a semifinal, and two of Canada. The games drew a total attendance of 243,517 and an average attendance of 27,057, second only to the Olympic Stadium in Montreal. The highest attendance was 32,058, which watched Canada play Congo.[77]

Two club friendly matches were played at Commonwealth in 2009 and 2010, under the Edmonton Cup umbrella. In the first, 15,800 spectators watched Argentinian side River Plate defeat England's Everton 1–0.[78] In the second, 8,792 spectators watched FC Edmonton play English side Portsmouth to a 1–1 draw.[79] A third club friendly was played in 2019 at Commonwealth Stadium between Cardiff City FC (English Football League) and Real Valladolid (La Liga Spain). Cardiff City fought out a 1–1 draw against the Spanish La Liga club, owned by Brazilian ace Ronaldo, before winning the penalty shoot-out 4–2. FC Edmonton started competing in the Canadian Championship in 2011 season and played these games at Commonwealth Stadium until 2014 when they returned to Clarke Stadium which is their regular home ground.[80] Commonwealth Stadium also hosted matches during the 2014 FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup between August 5 and 24,[76] and the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup between June 5 and July 6.[81]

| Date | Time (MDT) | Team #1 | Result | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 June 2015 | 16:00 | Canada | 1–0 | China | Group A | 53,058 |

| 19:00 | New Zealand | 0–1 | Netherlands | 53,058 | ||

| 11 June 2015 | 16:00 | China | 1–0 | Netherlands | 35,544 | |

| 19:00 | Canada | 0–0 | New Zealand | 35,544 | ||

| 16 June 2015 | 15:00 | Switzerland | 1–2 | Cameroon | Group C | 10,177 |

| 18:00 | Australia | 1–1 | Sweden | Group D | 10,177 | |

| 20 June 2015 | 17:30 | China | 1–0 | Cameroon | Round of 16 | 15,958 |

| 22 June 2015 | 18:00 | United States | 2–0 | Colombia | 19,412 | |

| 27 June 2015 | 14:00 | Australia | 0–1 | Japan | Quarterfinals | 19,814 |

| 1 July 2015 | 17:00 | Japan | 2–1 | England | Semifinals | 31,467 |

| 4 July 2015 | 14:00 | Germany | 0–1 | England | Third place play-off | 21,483 |

Concerts

editConcerts held at Commonwealth Stadium include Pink Floyd, Beyoncé, David Bowie, Tim McGraw, Genesis, the Rolling Stones, the Police, Fiction Plane, AC/DC, Metallica, U2, Kenny Chesney, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Taylor Swift, Bon Jovi, Guns N' Roses, Lilith Fair, Mötley Crüe, Edgefest and One Direction.

Ice hockey

editThe 2003 Heritage Classic was an outdoor ice hockey game played on November 22 between the National Hockey League (NHL) sides Edmonton Oilers and the Montreal Canadiens. The first regular-season NHL game to be played outdoors, it saw the Canadiens win 4–3 in front of a crowd of 57,167, despite temperatures of close to −18 °C,[88] −30 °C (−22 °F) with wind chill.[89] It was held to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Oilers joining the NHL in 1979 and the 20th anniversary of their first Stanley Cup win in 1984. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television broadcast drew 2.747 million viewers in Canada, the second-highest audience for a regular-season NHL game.[88] The 2023 Heritage Classic was played at Commonwealth Stadium, where the Edmonton Oilers hosted the Calgary Flames in the first outdoor NHL “Battle of Alberta” [90] where the Oilers won 5–2.[91]

Rugby union

editCommonwealth Stadium has been used to host Churchill Cup matches. The 2004 edition had the first round played in Calgary and the second round played at Commonwealth Stadium.[92] The 2005 edition saw all matches being played in Edmonton, with the final drawing a crowd of 17,000.[93] In the 2006 edition the three finals were played at Commonwealth Stadium.[94] The 2006 Women's Rugby World Cup was hosted in Edmonton and its suburb, St. Albert. Most of the Edmonton games were played at Ellerslie Rugby Park, but the final, third-place match and fifth-place match were all played at Commonwealth Stadium.[95][96] On June 9, 2018, the Canadian Men's National team played host to Scotland, world number 6 at the time, in a test match at Commonwealth Stadium. Scotland came away with a 48–10 victory over Canada in front of a crowd of 12,824 at Commonwealth Stadium.

Other events

editIn 1980, the venue hosted a Billy Graham event during his Northern Canada Crusade.[97]

In 1983, the Edmonton Trappers Triple-A baseball team defeated the California Angels of Major League Baseball in an exhibition baseball game witnessed by a crowd of 24,830.

On 26 July 2022, Pope Francis led an open-air Mass in front of an attendance of nearly 50,000 people as part of his first visit to Canada.

On 30 July 2022, Monster Jam made its only appearance at the stadium.

In 2024, it hosted the IFAF U20 World Junior Championship, marking the first time American football was played at the stadium.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Known as the Edmonton Elks since 2021.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e 1688 to 1923: Geloso, Vincent, A Price Index for Canada, 1688 to 1850 (December 6, 2016). Afterwards, Canadian inflation numbers based on Statistics Canada tables 18-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0021) "Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted". Statistics Canada. Retrieved April 17, 2021. and table 18-10-0004-13 "Consumer Price Index by product group, monthly, percentage change, not seasonally adjusted, Canada, provinces, Whitehorse, Yellowknife and Iqaluit". Statistics Canada. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Payne, Michael. "History of Commonwealth Stadium". City of Edmonton. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Edmonton rejects costly roof". The Leader-Post. December 12, 1975. p. 46. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Herzog, Lawrence. "Commonwealth Stadium Marks 25 Years". Inside Edmonton. 21 (30): July 31, 2003. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Status of Edmonton Stadiums". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Herzog, Lawrence. "When the LRT came to Edmonton". It's Our Heritage. 26 (38): September 25, 2008. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Home Stadiums of the Edmonton Eskimos". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c Sarrazin, Megan (May 10, 2010). "Artificial turf on the way: Commonwealth Stadium losing grass". Canoe. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c "Edmonton FieldTurf fast facts". Canadian Football League. May 10, 2010. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Jones, Terry (November 28, 2009). "A season of league-wide ups and downs in the CFL". Edmonton Sun. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "MJMArchitects: commonwealth community recreation center, edmonton". Designboom. May 28, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "Commonwealth Recreation Centre". Clark Builders. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Jones, Terry (April 10, 2012). "Esks fans sittin' pretty". Edmonton Sun. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Jones, Terry (February 22, 2011). "Esks benefit from Cup success". Edmonton Sun. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Eskimos receivers Fred Stamps, Adarius Bouwman like the newly squared-off corners".

- ^ "Edmonton's Commonwealth Stadium field gets name change - Edmonton | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ "Edmonton Elks to close upper bowl of Commonwealth Stadium for 2024 season - Edmonton | Globalnews.ca".

- ^ "Executive Suites". Edmonton Eskimos. Archived from the original on September 30, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Jones, Terry (May 11, 2010). "Eskimos home makeover". Canoe. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Griwkowsky, Con (June 2, 2014). "Eskimos receivers Fred Stamps, Adarius Bouwman like the newly squared-off corners". Edmonton Sun. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "List of Certified Athletics Facilities" (PDF). International Association of Athletics Federations. June 3, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Clarke Field". City of Edmonton. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Football Park & Ride". City of Edmonton. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1977 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1979 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Eskimos set new attendance record". Edmonton Eskimos. September 26, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Green light means go for new turf at Commonwealth Stadium". Edmonton Eskimos. March 10, 2010. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1978 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1980 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1981 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1982 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1983 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1984 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1985 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1986 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1987 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1988 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1989 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1990 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1991 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1992 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1993 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1994 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1995 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1996 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1997 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1998 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 1999 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2000 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2001 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2002 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2003 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2004 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2005 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2006 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2007 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2008 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2009 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2010 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2011 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Edmonton Eskimos' 2012 Season". CFLDB. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Jones, Terry (November 29, 2010). "Grey Cup a record-breaker". Edmonton Sun. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Crossley, Andy (February 19, 2013). "1979–1982 Edmonton Drillers". Fun While It Lasted. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "NASL Franchise Cumulatiave Records". NASL Homepage. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Fixtures & Results". Canadian Soccer Association. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Morrison, Neil (November 25, 1999). "Canada Cup 1995 (Canada)". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Bobrowsky, Josef; Pierrend, José Luis (March 1, 2003). "Maple Cup 1999". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "'Welcome to the Iceteca': Canada ready for frigid World Cup qualifier". sportsnet.ca. November 16, 2021.

- ^ "Three Takeaways from Canada's historic Iceteca win over Mexico". Major League Soccer. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ "Sources: Canada loss Mexico's coldest on record". ESPN.com. November 17, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ a b "Fixtures & Results". Canadian Soccer Association. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "History". Canadian Soccer Association. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "About CONCACAF Men's Olympic Qualification". CONCACAF. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Shtutin, Eugene; Aarhus, Lars (December 7, 2003). "Games of the XXVI. Olympiad". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "U-19 Women's World Championship Canada 2002" (PDF). FIFA. pp. 10, 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 26, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "Edmonton". FIFA. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "FIFA U-20 World Cup Canada 2007: Technical Report and Statistics" (PDF). FIFA. pp. 68, 88–89. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 20, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "River Plate edges Everton in Edmonton". CBC Sports. July 26, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Portsmouth downs FC Edmonton in shootout". The Globe and Mail. July 22, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Vancouver edges Edmonton in first leg of semifinal". NBC Sports. April 25, 2013. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Edmonton". FIFA. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "AC/DC Coming Back To Canada | News @". Ultimate-guitar.com. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ^ Sperounes, Sandra (June 2, 2011). "Bono dedicates final U2 song to Slave Lake fire victims". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ Sperounes, Sandra (May 21, 2016). "Beyonce dazzles in the drizzle at Commonwealth Stadium". Edmonton Journal. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ "Guns N Roses - Live in Edmonton 2017 - Wichita Lineman (Glen Campbell Tribute)". jzalapski at YouTube.com. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ "See Guns N' Roses' Surprise Cover of Glen Campbell's 'Wichita Lineman'". RollingStone.com. August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ "Guns N' Roses Jam James Brown + Glen Campbell Classics Live". Loudwire. August 31, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ^ a b "The NHL moves outdoors". CBC Sports. December 27, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ^ "Hourly Data Report for November 22, 2003". Canada's National Climate Archive. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Oilers to host Flames in Heritage Classic at Commonwealth Stadium next season – Sportsnet.ca". www.sportsnet.ca. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ "Oilers defeat Flames at Heritage Classic, end 4-game skid | NHL.com". www.nhl.com. October 30, 2023. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ "Black Ferns claim Churchill Cup". TVNZ News. June 20, 2004. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "England recapture Churchill Cup". BBC Sport. June 26, 2005. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "NZ Maori in 2006 Churchill Cup". TVNZ News. November 1, 2005. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "The year in detail" (PDF). Australian Rugby Union. 2007. p. 83. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "2006: New Zealand retain Women's RWC crown". 2014 Women's Rugby World Cup. September 17, 2006. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Billy Graham History". Billy Graham Evangelistic Association of Canada. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.